The Great Friendship

The Great Friendship (Russian: Великая дружба Velikaya druzhba; also called The Extraordinary Commissar) is a 1947 opera by Vano Muradeli, to a libretto by Georgi Mdivani. It was premiered in Donetsk (then known as Stalino) on 28 September 1947 and given its Moscow premiere at the Bolshoi Theatre, on 7 November 1947. Joseph Stalin attended a performance at the Bolshoi on 5 January 1948, and strongly disapproved of the opera. This led to a significant purge, often referred to as the Zhdanovshchina, of the musical life of the Soviet Union.

Background

The opera was first mooted in 1941 as a homage to Sergo Ordzhonikidze, a leading Bolshevik revolutionary, later a member of the CPSU Politburo and long-time close associate of Stalin, who in 1937 had shot himself anticipating arrest from his former friend, but whose death had at the time been given out as caused by heart failure. During the Russian Civil War, Ordzhonikidze, by birth (like Stalin) a Georgian, was a commissar for Ukraine, fighting the White Army under Anton Denikin. The opera, which is set during Ordzhonikidze's campaign against Denikin, appeared in the 1941 workplan of the Bolshoi Theatre with Muradeli named as composer; it was at that time named The Special Commissar (Чрезвычайный комиссар).[1]

Muradeli, who had himself been present at a meeting with Ordzhonikidze in Gori in 1921, had himself proposed the idea of the opera, the storyline of which also drew from Ordzhonikidze's account of his campaign in the Caucasus in his book The Path of a Bolshevik.[2] On 22 January 1947 the opera, under the name of The Special Commissar, appeared in Order no. 40 published by the Arts Committee of the Council of People's Commissars in the list of works intended to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the October Revolution (7 November 1917)[3] The title of the opera was changed in May 1947, (possibly at the suggestion of the censorship authorities) to The Great Friendship, referring to the friendship between the many peoples of the Soviet Union.[4]

The opera's premiere was at Stalino (now Donetsk), Ukraine, on 28 September 1947. Other performances were arranged at other cities including Leningrad, Gorki (now Nizhny-Novgorod), Yerevan, Ulan-Ude, Frunze (now Bishkek), Novosibirsk, Riga and Vilnius. A concert performance in Kiev was broadcast on radio.[2] The first performance in Moscow at the Bolshoi Theatre on 7 November 1947, (the date of the Revolution's 30th anniversary), was conducted by Alexander Melik-Pashayev. It was directed by Boris Pokrovsky, and designed by Fyodor Fedorovsky.[4]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Cast of Moscow premiere, Bolshoi Theatre, 7 November 1947[5] |

|---|---|---|

| Commissar | baritone | David Gamrekeli |

| Murtaz | tenor | Georgi Nelepp |

| Galina | soprano | N. Chubenko |

| Fyodor | bass | Maxim Mikhailov |

| Ismail | D. Mchedeli | |

| Pomazov | A. P. Ivanov | |

| Dzhemal, an old shepherd | tenor | Anatoli Orfenov |

Synopsis

The opera is set in the year 1919 in northern Georgia, and is in five scenes, as follows:

- A valley of the Terek River.

- The hut of the Cossack Fyodor.

- A mountain village in the Caucasus.

- A shepherd's cave.

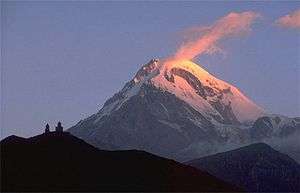

- The foothills of Mount Kazbek.[6]

The Lezgin Murtaz and the Cossack girl Galina are in love with each other. In the context of the historic rivalry between the Cossacks and the mountain folk of the Caucasus, this has some echo of the story of Romeo and Juliet. A Bolshevik commissar (Ordzhonikidze) visits to persuade the local population to support the Revolution. Murtaz is on the Bolshevik side; he dies heroically stopping a bullet aimed at the Commissar by the opera's villain, the White officer Pomazov.[7]

Murtaz's dying words to Galina are: "The great Lenin showed us the way. Stalin will lead us through the storms to defeat the enemy."[8]

Reception

Dmitri Shostakovich, recalling in 1960 the Moscow premiere, felt that the opera was perfectly satisfactory both as regards the production and the performances.[9] The first two performances at the Bolshoi were well received by the audiences. On 5 January 1948, however, Stalin visited the third performance at the Bolshoi in the company of other Politburo members.[10] In his memoirs as edited by Solomon Volkov, Shostakovich comments: "Everything seems to have augured success for Muradeli. The plot had ideology, from the lives of the Georgians and Ossetians. [...] Ordzhonikidze was a character in the opera, he was cleaning up the Caucasus. The composer was also of Caucasian descent. What more could you ask?"[11]

Shostakovich goes on to itemize three aspects which in fact enraged Stalin. Stalin himself was of Ossetian descent, and felt that in the opera the Ossetians were marginalized by Georgians, and that the opera did not sufficiently demonize other peoples (including Chechens and Ingush) whom at the time he was deporting from the region. Stalin also took offence at praise of Ordzhonikidze; although Ordzhonikidze was officially a Bolshevik hero, Stalin was reminded that he had driven his old friend to suicide. Finally Stalin was offended that, instead of using the traditional lezginka dance melody in the opera (a tune which was one of Stalin's favourites), Muradeli had composed his own lezginka tune.[12]

.jpg)

Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin's adviser on cultural policy, saw this as an opportunity to launch an attack on Russian musical culture similar to the attacks he had already undertaken on literature, cinema and the theatre.[13] Zhdanov began questioning the performers of the opera, trying to persuade them to dissociate themselves from the work.[14]

A Resolution by the Politburo, "On Muradeli's Opera The Great Friendship", condemning formalism in music was issued on 10 February 1948, claiming that "In his desire to achieve a falsely conceived ‘originality’, Muradeli ignored and disregarded the finest traditions and experience of classical opera, and particularly of Russian classical opera." [15] Muradeli had acknowledged his 'errors' and blamed them on the influence of Shostakovich.[16]

The Resolution named six composers (Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Nikolai Miaskovsky, Aram Khachaturian, Vissarion Shebalin and Gavriil Popov) as 'formalists', damaging their careers and effectively preventing their music being programmed until they 'repented'. Many dismissals were made at the Composers Union and purges there continued under the newly-appointed General Secretary of the Union, Zhdanov's protegé Tikhon Khrennikov.[17]

It was not until two years after the death of Stalin that the 1948 Resolution was rescinded. A new decree was issued on 28 March 1958 by the Central Committee, entitled "On the Correction of Errors in the Evaluation of The Great Friendship, Bogdan Khmelnitsky and From All My Heart" (two other works which had fallen foul of Zhdanov's campaigns). The singer Galina Vishnevskaya recalled attending a private party given by Shostakovich to celebrate the new decree, at which the composer "proposed a toast to the great historical Decree "On Abrogating the Great Historical Decree"", and sang Zhdanov's words "There must be beautiful music; there must be refined music" to the melody of Stalin's favourite lezginka.[18]

A revised version of the opera was prepared by Muradeli in 1960 and this was premiered in the town of Ordzhonikidze (today Vladikavkaz) in 1970.[19]

References

Notes

- Vlasova (2010), p. 223.

- Vlasova (2010), p. 224.

- Vlasova (2010), pp. 218–220.

- Vlasova (2010), p. 225

- Vlasova (2010), p. 228

- Vlasova (2010), p. 230.

- Vlasova (2010), pp. 228–233.

- Vlasova (2010), p. 236.

- Cited in Vlasova (2010), p. 236.

- Frolova-Walker (2016), p. 222.

- Volkov (1995), pp. 142–3.

- Volkov (1995), p. 143.

- Wilson (1994), p. 200.

- Frolova-Walker (2016), p. 223.

- For the text in English see Revolutionary Democracy website, accessed 25 April 2017.

- Wilson (1994), p. 208

- Frolova-Walker (2016), p. 226.

- Wilson (1994), pp. 292–293.

- "Мурадели Вано Ильич" in Great Soviet Encyclopedia online, accessed 30 April 2017.

Sources

- Frolova-Walker, Marina (2016). Stalin's Music Prize: Soviet Culture and Politics. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300208849

- Vlasova, Ekaterina (2010). 1948 год в советской музике (The Year 1948 in Soviet Music). Moscow: Klassika-21. ISBN 9785898173234

- Volkov, Solomon (1995). Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. New York: Limelight Editions. ISBN 9780879100216

- Wilson, Elizabeth (1994). Shostakovich: A Life Remembered. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571174867