Reformed Political Party

The Reformed Political Party (Dutch: Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij, SGP) is an orthodox Calvinist[12] political party in the Netherlands. The term Reformed is not a reference to political reform but is a synonym for Calvinism—a major branch of Protestantism. The SGP is the oldest political party in the Netherlands in its current form and has been in opposition for its entire existence. Owing to its orthodox political ideals and its traditional role in the opposition, the party has been called a testimonial party. Since the general election of 2017, it has held 3 of the 150 seats of the House of Representatives.

The party has traditionally opposed universal suffrage, seeking to replace this with a form of "organic suffrage" (Dutch: huismanskiesrecht, "suffrage of the pater familias") restricted to male heads of households. It also advocates the reestablishment of capital punishment in the Netherlands, which was abolished by a House of Representatives vote in 1870.

Party history

Foundation

The SGP was founded on 24 April 1918, by several conservative members of the Protestant Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP). They did not support female suffrage, which the ARP had made possible. Furthermore, they were against the alliance the ARP had formed with the General League of Roman Catholic Caucuses. The leading figure in the party's foundation was Yerseke pastor Gerrit Hendrik Kersten, who envisioned a Netherlands "without cinema, sports, vaccination and social security".[13]

1922–1945

The party entered the 1918 general elections, but was unable to win any seats. In the 1922 election the party entered Parliament when Kersten won a seat in the House of Representatives. In this period the SGP became most noted for proposing, during the annual parliamentary debate on the budget of the Foreign Affairs Ministry, to abolish Dutch representation to the Holy See. Each year the Protestant Christian Historical Union (CHU) also voted in favour of this motion. The CHU was in cabinet with the Catholic General League, but many of its members and supporters still had strong feelings against the Catholic Church. In 1925, the left-wing opposition (the Free-thinking Democratic League and Social Democratic Workers' Party) also voted in favour of the motion. They were indifferent to the representation at the Holy See, but saw the issue as an opportunity to divide the confessional cabinet. The cabinet fell over this issue, in what is known as the Nacht van Kersten ("Night of Kersten").

The party gained another seat in the 1925 election, and a third seat in the 1929 election. It retained three seats in the 1933 election, but lost a seat in the 1937 election, in which the ARP led by prime minister Hendrikus Colijn performed particularly well. During World War II, Kersten cooperated with the German occupiers to allow his paper, the Banier, to be printed. He also condemned the Dutch Resistance, saying the German invasion was divine retribution for desecrating the Lord's Day. After the war, he was branded a collaborator and permanently stripped of his seat in the House of Representatives.

1945–present

Kersten was succeeded by Pieter Zandt, under whose leadership the SGP was very stable, continually getting 2% of votes. In the 1956 election, the SGP profited from the enlargement of Parliament, and entered the Senate for the first time. It lost that seat in 1960, but regained it in 1971. In 1961 Zandt died and was succeeded by Cor van Dis sr., a chemist. After ten years he stood down in favour of Reverend Hette Abma, who also stepped down after ten years, in favour of Henk van Rossum, a civil engineer. In the 1984 European Parliament election, the SGP joined the two other orthodox Protestant parties (the Reformatory Political Federation (RPF) and the Reformed Political League (GPV)). They won one seat in the European Parliament, which was taken by SGP member Leen van der Waal, a mechanical engineer. In 1986, Van Rossum was succeeded by Bas van der Vlies, who led the party till March 2010, when he was succeeded by Kees van der Staaij. In the 1994 election the party lost one seat in the House, regained it in 1998, and lost it again in 2002. After the general election of 2003, the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) and the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) held talks with the SGP — the first time in memory that the SGP was seriously considered as a possible coalition partner. Ultimately, the Democrats 66 joined the second Balkenende cabinet instead of the SGP, mostly because of the ideological differences between VVD and SGP.

On 7 September 2005, the district court of The Hague judged that the party could no longer receive subsidies from the government, because women were not allowed to hold positions in the party. This was found to be a violation of the 1981 UN Treaty on Women in which the Netherlands committed to fighting discrimination. It also was a violation of the first article of the Dutch constitution, the principle of non-discrimination. The Dutch Council of State overturned the decision nevertheless, maintaining that a party's political philosophy takes precedence, and that women have the opportunity to join other political parties where they can obtain a leadership role.[14]

Female members of the Reformed Political Party Youth (SGPJ), which did allow female membership, said however that they did not feel discriminated or repressed. During a party congress on 24 June 2006, the SGP lifted the ban on female membership. Political positions inside and outside the party are open to women. On 19 March 2014, the first female SGP delegate was elected to the municipal council in Vlissingen.[15]

Ideology and issues

As a Protestant fundamentalist party,[11] the SGP draws much from its ideology from the reformed tradition, specifically the ecclesiastical doctrinal standards known as the Three Forms of Unity, including an unamended version of the Belgic Confession (Nederlandse Geloofsbelijdenis). The latter text is explicitly mentioned in the first principle of the party,[16] where it is stated that the SGP strives towards a government totally based on the Bible. This first principle also states that the uncut version of the Belgic Confession is meant, which adds the task of opposing anti-Christian powers to the description of the government's roles and tasks.[17] The party is a strict defender of the separation between church and state,[18] rejecting "both the state church and church state". Both church and state are believed to have distinct roles in society, while working towards the same goal, but despite this, some accuse the SGP of advocating for theocracy.[19] The SGP opposes freedom of religion, but advocates freedom of conscience instead, noting that "the obedience to the Law of God cannot be forced".[20]

The SGP opposes feminism, and concludes, on Biblical grounds, that men and women are of equal value (gelijkwaardig) but inherently different (gelijk).[21] Men and women, so the party claims, have different places in society. This belief led to restricting party membership to men until 2006, when this restriction became subject to controversy[22] and was eventually removed.[23] It has traditionally opposed universal suffrage, seeking to replace this with a form of "organic suffrage" (Dutch: huismanskiesrecht, "suffrage of the pater familias") restricted to male heads of households.[24] In the 2018 local elections, the party for the first time allowed several women to lead lists.[25]

In controversial discussions in the Dutch House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer), the SGP often stresses the importance of the rule of law, parliamentary procedure and rules of order, regardless of ideological agreement. The party favours the re-introduction of the death penalty in the Netherlands. They base this on the Bible, specifically on Genesis 9:6, "Whoso sheddeth man's blood, by man shall his blood be shed: for in the image of God made he man", and Exodus 21:12, "He that smiteth a man, so that he die, shall be surely put to death."

Electoral results

| Election year | House of Representatives | Government | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | |||

| 1977 | 177,010 | 2.1 (#5) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 1981 | 171,324 | 2.0 (#7) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 1982 | 156,636 | 1.9 (#6) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 1986 | 159,740 | 1.7 (#5) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 1989 | 166,082 | 1.9 (#6) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 1994 | 155,251 | 1.7 (#9) | 2 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 1998 | 153,583 | 1.8 (#8) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 2002 | 163,562 | 1.7 (#9) | 2 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 2003 | 150,305 | 1.6 (#9) | 2 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 2006 | 153,266 | 1.6 (#10) | 2 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 2010 | 163,581 | 1.7 (#9) | 2 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 2012 | 196,780 | 2.1 (#9) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

| 2017 | 218,950 | 2.1 (#11) | 3 / 150 |

in opposition | ||

This is a list of representations of Reformed Political Party in the Dutch parliament, as well as the provincial, municipal and European elections. The party's lijsttrekker has been the same as the fractievoorzitter (parliamentary group leader) of that year in every election.

Leadership

House of Representatives

Since the 2012 elections the party has had three representatives in the House of Representatives:

- Kees van der Staaij, Parliamentary group leader

- Roelof Bisschop

- Elbert Dijkgraaf (stepped down on 11 April 2018, replaced by Chris Stoffer)[26]

Senate

Since the 2015 Senate elections, the party has had two representatives in the Senate:

- Peter Schalk, Senate group leader

- Diederik van Dijk

European Parliament

Since the 1984 European Parliament election the party has one elected representative in the European Parliament. From 1984 to 1997 Leen van der Waal was the representative, from 1999 until now Bas Belder is the party's representative. In the European elections, the SGP formed one parliamentary party with the Christian Union, called Christian Union-SGP. It was part of the Independence/Democracy (Ind/Dem) European parliamentary group. Following the results of the 2009 European Parliament elections, the Ind/Dem group was disbanded, and the SGP joined the Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) European parliamentary group. After the 2014 European Parliament elections, the SGP left the EFD and joined the Christian Union in the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group:[27]

- Bas Belder, member

Municipal and provincial government

Provincial government

In provincial governments, the party participates in the Zeeland provincial executive.[28] There, the party is the strongest, with over 10% of the vote. It has 18 members of provincial legislature independently, while another two seats were won by combined lists with the Christian Union.

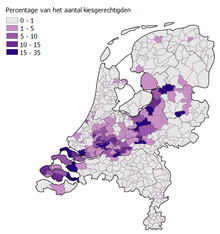

The table below shows the election results of the 2019 provincial election in each province. It shows the areas where the Reformed Political Party is strong, namely in the Bible Belt: a band from Zeeland, via parts of South Holland and Utrecht, Gelderland to Overijssel.

| Province | Votes (%) | Result (seats) |

|---|---|---|

| Zeeland | 12.06 | 5 / 39 |

| Gelderland | 5.25 | 3 / 55 |

| Overijssel | 3.91 | 2 / 47 |

| South Holland | 3.90 | 2 / 55 |

| Flevoland | 3.84 | 1 / 41 |

| Utrecht | 3.54 | 1 / 49 |

| North Brabant* | 1.92 | 1 / 55 |

| Friesland | 1.07 | 0 / 43 |

| Drenthe | 0.82 | 0 / 41 |

| Groningen | Did not contest | |

| Limburg | Did not contest | |

| North Holland | Did not contest | |

* result of combined ChristianUnion/SGP lists.

Municipal government

6 of the 342 mayors of the Netherlands are members of the SGP,[29] and the party participates in several local executives, usually in municipalities located within the Bible Belt. The party has 40 aldermen and 244 members of local legislature. In many municipalities where the SGP is weaker, it cooperates with the ChristenUnie, presenting common lists.

Electorate

The SGP has had a very stable electorate since first entering the States-General in 1922. Since winning a second seat in 1926, it has usually varied between two and three seats in the House of Representatives. The party has been called “an almost perfect illustration of Duverger's category of 'fossilised' minor party."[30]

Most of its electorate is formed by so-called "bevindelijk gereformeerden", Reformed Christians for whom personal religious experience is very important. This group is formed by several smaller churches such as the Christian Reformed Churches, Reformed Congregations, Restored Reformed Church, and Old-Reformed Congregations in the Netherlands, as well as the conservative wing of the Protestant Church in the Netherlands, the Reformed Association. However, not all members of these churches / church wings vote SGP.

The SGP's support is concentrated geographically in the Dutch bible belt, a band of strongly Reformed municipalities ranging from Zeeland in the South via Goeree-Overflakkee and the Alblasserwaard in South Holland and the Veluwe in Gelderland to the Western part of Overijssel, around Staphorst. The SGP is also very strong on the former island Urk and also in Uddel; in both places it received a majority of the vote in 2017.[31]

Organisation

Organisational structure

The highest organ of the SGP is the congress, which is formed by delegates from the municipal branches. It convenes once every year. It appoints the party board and decides the order of the Senate, House of Representatives, European Parliament candidates list and has the last say over the party program. The SGP chairman is always a minister. Since 2001 this position is ceremonial, as the general chair leads the party's organisation.

The party has 245 municipal branches and has a provincial federation in each province, except for Limburg.

Linked organisations

The party publishes the Banner two-weekly since 1921. The scientific institute of the party is called the Guido de Brès-foundation, which publishes the magazine Zicht (Sight). The youth organisation of the SGP is called the Reformed Political Party Youth (SGPJ), which with its approximately 12,000 members is the largest political youth organization in the Netherlands.

The SGP participates in the Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy, a democracy assistance organisation of seven Dutch political parties.

Pillarised organisations

The SGP still has close links with several other orthodox Protestant organisations, such as several reformed churches and the newspaper Reformatorisch Dagblad. Together they form a small but strong orthodox-reformed pillar.

Relationships to other parties

Until 1963, the SGP was relatively isolated in parliament. The strongly antipapal SGP refused to cooperate with either the Catholic People's Party or the secularist People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) and Labour Party (PvdA). The larger Protestant Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP) had some sympathy for the party, but cooperated tightly with the KVP and the Protestant Christian Historical Union (CHU). In 1963 another orthodox Protestant party, the Reformed Political League (GPV) entered parliament, in 1981 they were joined by the Reformatory Political Federation (RPF). Together these three parties formed the "Small Christian parties". They shared the same orthodox Protestant political ideals and had the same political strategy, as testimonial parties. They cooperated in municipalities, both in municipal executives, where the parties were strong, as well as in common municipal parties, where the parties were weak. In the 1984 European Parliamentary election the parties presented a common list and they won one seat in parliament. After 1993 the cooperation between the GPV and the RPF intensified, but the SGP's position at the time on female suffrage prevented the SGP joining this closer cooperation. However, in 2000 the GPV and RPF merged to form the ChristianUnion (CU). Traditionally the SGP and the CU worked together closely as they were both based on Protestant Christian politics. Recently however, as the CU has moved more towards the centre-left, discernible differences of philosophy between the SGP and CU have caused the parties to not join together in elections. The most notable example was the 2011 senate election where the SGP and CU did not combine their votes.[32]

Prime Minister Mark Rutte's first government depended on the SGP's support in the Senate to pass legislation where it fell one seat short of a majority in the 2011 provincial elections.[33] As a result, the party was able to achieve a number of its own political objectives: continuing child support for larger families,[34] and restricting business hours on Sundays.[35] As previously mentioned, it was seriously considered as a coalition partner in 2003. These are among the few times in recent memory that the SGP has had any national impact.

Notes

- "Forum voor Democratie qua ledental de grootste partij van Nederland" (PDF). Documentatiecentrum Nederlandse Politieke Partijen (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2017). "Netherlands". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Wijbrandt van van Schuur; Gerrit Voerman (2010). "Democracy in Retreat? Decline in Political Party Membership: The Case of the Netherlands". In Barbara Wejnert (ed.). Democratic Paths and Trends. Emerald. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-85724-091-0. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Jean-Yves Camus (2013). "The european extreme right and religious extremism". In Andrea Mammone; Emmanuel Godin; Brian Jenkins (eds.). Varieties of Right-Wing Extremism in Europe. Routledge. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-136-16751-5.

- Brent F. Nelsen; James L. Guth (2015). Religion and the Struggle for European Union: Confessional Culture and the Limits of Integration. Georgetown University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-1-62616-070-5.

- Christoph Jedan (2013). "Overcoming the divide between religious and secular values: Introductory essay". In Christoph Jedan (ed.). Constellations of Value: European Perspectives on the Intersections of Religion, Politics and Society. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 14. ISBN 978-3-643-90083-8.

- Benjamin LeRuth; Yordan Kutiyski; André Krouwel; Nicholas J Startin (2017). "Does the Information Source Matter? Newspaper Readership, Political Preferences and Attitudes Toward the EU in the UK, France and the Netherlands". In Manuela Caiani; Simona Guerra (eds.). Euroscepticism, Democracy and the Media: Communicating Europe, Contesting Europe. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-137-59643-7.

- Arthur S. Banks; Thomas C. Muller; William Overstreet; Sean M. Phelan; Hal Smith (2000). Political Handbook of the World 1999. Cq Pr. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-933199-14-9.

- Nicola Maggini (2016). Young People's Voting Behaviour in Europe: A Comparative Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-137-59243-9.

- Voerman, Gerrit; Lucardie, Paul (July 1992). "The extreme right in the Netherlands. The centrists and their radical rivals". European Journal of Political Research. 22 (1): 36, 51. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1992.tb00304.x.

- Amir Abedi (2004). Anti-political Establishment Parties: A Comparative Analysis. Psychology Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-415-31961-4.

- These sources describe the SGP as a Calvinist political party:

- J Denis Derbyshire; Ian Derbyshire (1989). Political Systems Of The World. Allied. p. 119. ISBN 978-81-7023-307-7.

- Veit Bader (2008). Secularism or Democracy?: Associational Governance of Religious Diversity. Amsterdam University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-90-5356-999-3. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Monique Leijenaar; Kees Niemöller (1997). "The Netherlands". In Pippa Norris (ed.). Passages to Power: Legislative Recruitment in Advanced Democracies. Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-521-59908-5. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- van Outeren, Emilie (2010-04-13). "Forcing a party to accept women easier said than done". Archief. NL: NRC. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- Dimitri Almeida (2012). The Impact of European Integration on Political Parties: Beyond the Permissive Consensus. CRC Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-136-34039-0. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- (in Dutch) Parlement.com biography

- "SGP will get subsidy after all". Expatica. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- "SGP-vrouw komt in raad Vlissingen". NOS. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- SGP 2003, p. 11.

- SGP 2003, p. 16.

- SGP 2003, p. 17.

- Dölle 2005, p. 104.

- SGP 2003, p. 27-28.

- SGP 2003, p. 37.

- "Party penalised for woman snub". BBC. 7 September 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- Davies 2006.

- Lucardie, Paul (2000). Right-Wing Extremism in the Netherlands: Why it is still a marginal phenomenon (PDF). Symp. Right-Wing Extremism in Europe.

- "Dit is de nieuwe, vrouwelijke lijsttrekker van de SGP".

- "SGP'er Chris Stoffer neemt zetel van Elbert Dijkgraaf in" Tweede Kamer, Accessed May 26, 2018.

- "Belder in ECR". 2014-06-16. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- College van Gedeputeerde Staten van Zeeland. "Nieuwe Verbindingen" (PDF) (in Dutch). Provincie Zeeland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- "Landelijk overzicht burgemeestersposten - 29 april 2015" (PDF) (in Dutch). Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Bone, Robert C (Feb 1962), "The Dynamics of Dutch Politics", The Journal of Politics, 24 (1): 43, doi:10.2307/2126736, JSTOR 2126736

- "Uitslagenkaart Tweede Kamerverkiezingen 2017 per stambureau".

- "ChristenUnie en SGP lastig door één deur". Nieuwslijn Magazine. 26 May 2011. Radio Netherlands Worldwide. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Netherlands: Caught between Geert Wilders and holy joes". EU: Presseurop. 2011-05-24. Archived from the original on 2011-11-28. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- "Dutch government U-turn on child benefit". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 2011-09-19. Archived from the original on 2011-09-21. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- "Press Review". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

References

- Davies, Gareth (2006). "Thou Shalt Not Discriminate Against Women". European Constitutional Law Review. 2: 152–66. doi:10.1017/S1574019606001520.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dölle, AHM (2005). De SGP onder vuur (PDF) (in Dutch). Centre for the Documentation of Dutch Political Parties (DNPP), of the University of Groningen. Retrieved 14 October 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hippe, J (1988). Reformatorisch Staatkundig Verbond? (PDF) (in Dutch). DNPP. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- SGP, Reformed Political Party (2006). Verkiezingsprogramma 2006-2011 – Naar eer en geweten (PDF) (in Dutch). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- SGP, Reformed Political Party (2003) [1996]. Toelichting op het Program van Beginselen van de Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (PDF) (in Dutch). 's-Gravenhage: Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij. ISBN 978-90-72164-10-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- NL Verkiezingen. "Dutch elections". Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Parlementair Documentatie Centrum. "Nacht van Kersten" (in Dutch). Parlement. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- Parlementair Documentatie Centrum. "G.H. Kersten" (in Dutch). Parlement. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- Parlementair Documentatie Centrum. "Staatkundig-Gereformeerde Partij (SGP)" (in Dutch). Parlement. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij. |

- Official website (closed on Sundays)

- European Parliament, NL: SGP