Robotics

Robotics is an interdisciplinary research area at the interface of computer science and engineering.[1] Robotics involves design, construction, operation, and use of robots. The goal of robotics is to design intelligent machines that can help and assist humans in their day-to-day lives and keep everyone safe. Robotics draws on the achievement of information engineering, computer engineering, mechanical engineering, electronic engineering and others.

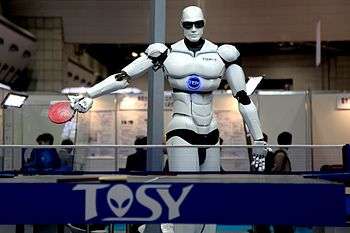

Robotics develops machines that can substitute for humans and replicate human actions. Robots can be used in many situations and for many purposes, but today many are used in dangerous environments (including inspection of radioactive materials, bomb detection and deactivation), manufacturing processes, or where humans cannot survive (e.g. in space, underwater, in high heat, and clean up and containment of hazardous materials and radiation). Robots can take on any form but some are made to resemble humans in appearance. This is said to help in the acceptance of a robot in certain replicative behaviors usually performed by people. Such robots attempt to replicate walking, lifting, speech, cognition, or any other human activity. Many of today's robots are inspired by nature, contributing to the field of bio-inspired robotics.

The concept of creating machines that can operate autonomously dates back to classical times, but research into the functionality and potential uses of robots did not grow substantially until the 20th century. Throughout history, it has been frequently assumed by various scholars, inventors, engineers, and technicians that robots will one day be able to mimic human behavior and manage tasks in a human-like fashion. Today, robotics is a rapidly growing field, as technological advances continue; researching, designing, and building new robots serve various practical purposes, whether domestically, commercially, or militarily. Many robots are built to do jobs that are hazardous to people, such as defusing bombs, finding survivors in unstable ruins, and exploring mines and shipwrecks. Robotics is also used in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) as a teaching aid.[2]

Robotics is a branch of engineering that involves the conception, design, manufacture, and operation of robots. This field overlaps with computer engineering, computer science (especially artificial intelligence), electronics, mechatronics, mechanical, nanotechnology and bioengineering.[3]

Etymology

The word robotics was derived from the word robot, which was introduced to the public by Czech writer Karel Čapek in his play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), which was published in 1920.[4] The word robot comes from the Slavic word robota, which means slave/servant. The play begins in a factory that makes artificial people called robots, creatures who can be mistaken for humans – very similar to the modern ideas of androids. Karel Čapek himself did not coin the word. He wrote a short letter in reference to an etymology in the Oxford English Dictionary in which he named his brother Josef Čapek as its actual originator.[4]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word robotics was first used in print by Isaac Asimov, in his science fiction short story "Liar!", published in May 1941 in Astounding Science Fiction. Asimov was unaware that he was coining the term; since the science and technology of electrical devices is electronics, he assumed robotics already referred to the science and technology of robots. In some of Asimov's other works, he states that the first use of the word robotics was in his short story Runaround (Astounding Science Fiction, March 1942),[5][6] where he introduced his concept of The Three Laws of Robotics. However, the original publication of "Liar!" predates that of "Runaround" by ten months, so the former is generally cited as the word's origin.

History

In 1948, Norbert Wiener formulated the principles of cybernetics, the basis of practical robotics.

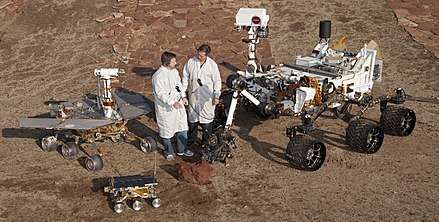

Fully autonomous robots only appeared in the second half of the 20th century. The first digitally operated and programmable robot, the Unimate, was installed in 1961 to lift hot pieces of metal from a die casting machine and stack them. Commercial and industrial robots are widespread today and used to perform jobs more cheaply, more accurately and more reliably, than humans. They are also employed in some jobs which are too dirty, dangerous, or dull to be suitable for humans. Robots are widely used in manufacturing, assembly, packing and packaging, mining, transport, earth and space exploration, surgery,[7] weaponry, laboratory research, safety, and the mass production of consumer and industrial goods.[8]

| Date | Significance | Robot name | Inventor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third century B.C. and earlier | One of the earliest descriptions of automata appears in the Lie Zi text, on a much earlier encounter between King Mu of Zhou (1023–957 BC) and a mechanical engineer known as Yan Shi, an 'artificer'. The latter allegedly presented the king with a life-size, human-shaped figure of his mechanical handiwork.[9] | Yan Shi (Chinese: 偃师) | |

| First century A.D. and earlier | Descriptions of more than 100 machines and automata, including a fire engine, a wind organ, a coin-operated machine, and a steam-powered engine, in Pneumatica and Automata by Heron of Alexandria | Ctesibius, Philo of Byzantium, Heron of Alexandria, and others | |

| c. 420 B.C | A wooden, steam propelled bird, which was able to fly | Flying pigeon | Archytas of Tarentum |

| 1206 | Created early humanoid automata, programmable automaton band[10] | Robot band, hand-washing automaton,[11] automated moving peacocks[12] | Al-Jazari |

| 1495 | Designs for a humanoid robot | Mechanical Knight | Leonardo da Vinci |

| 1738 | Mechanical duck that was able to eat, flap its wings, and excrete | Digesting Duck | Jacques de Vaucanson |

| 1898 | Nikola Tesla demonstrates first radio-controlled vessel. | Teleautomaton | Nikola Tesla |

| 1921 | First fictional automatons called "robots" appear in the play R.U.R. | Rossum's Universal Robots | Karel Čapek |

| 1930s | Humanoid robot exhibited at the 1939 and 1940 World's Fairs | Elektro | Westinghouse Electric Corporation |

| 1946 | First general-purpose digital computer | Whirlwind | Multiple people |

| 1948 | Simple robots exhibiting biological behaviors[13] | Elsie and Elmer | William Grey Walter |

| 1956 | First commercial robot, from the Unimation company founded by George Devol and Joseph Engelberger, based on Devol's patents[14] | Unimate | George Devol |

| 1961 | First installed industrial robot. | Unimate | George Devol |

| 1967 to 1972 | First full-scale humanoid intelligent robot,[15][16] and first android. Its limb control system allowed it to walk with the lower limbs, and to grip and transport objects with hands, using tactile sensors. Its vision system allowed it to measure distances and directions to objects using external receptors, artificial eyes and ears. And its conversation system allowed it to communicate with a person in Japanese, with an artificial mouth.[17][18][19] | WABOT-1 | Waseda University |

| 1973 | First industrial robot with six electromechanically driven axes[20][21] | Famulus | KUKA Robot Group |

| 1974 | The world's first microcomputer controlled electric industrial robot, IRB 6 from ASEA, was delivered to a small mechanical engineering company in southern Sweden. The design of this robot had been patented already 1972. | IRB 6 | ABB Robot Group |

| 1975 | Programmable universal manipulation arm, a Unimation product | PUMA | Victor Scheinman |

| 1978 | First object-level robot programming language, allowing robots to handle variations in object position, shape, and sensor noise. | Freddy I and II, RAPT robot programming language | Patricia Ambler and Robin Popplestone |

| 1983 | First multitasking, parallel programming language used for a robot control. It was the Event Driven Language (EDL) on the IBM/Series/1 process computer, with implementation of both inter process communication (WAIT/POST) and mutual exclusion (ENQ/DEQ) mechanisms for robot control.[22] | ADRIEL I | Stevo Bozinovski and Mihail Sestakov |

Robotic aspects

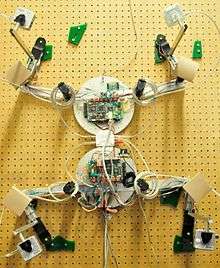

There are many types of robots; they are used in many different environments and for many different uses. Although being very diverse in application and form, they all share three basic similarities when it comes to their construction:

- Robots all have some kind of mechanical construction, a frame, form or shape designed to achieve a particular task. For example, a robot designed to travel across heavy dirt or mud, might use caterpillar tracks. The mechanical aspect is mostly the creator's solution to completing the assigned task and dealing with the physics of the environment around it. Form follows function.

- Robots have electrical components which power and control the machinery. For example, the robot with caterpillar tracks would need some kind of power to move the tracker treads. That power comes in the form of electricity, which will have to travel through a wire and originate from a battery, a basic electrical circuit. Even petrol powered machines that get their power mainly from petrol still require an electric current to start the combustion process which is why most petrol powered machines like cars, have batteries. The electrical aspect of robots is used for movement (through motors), sensing (where electrical signals are used to measure things like heat, sound, position, and energy status) and operation (robots need some level of electrical energy supplied to their motors and sensors in order to activate and perform basic operations)

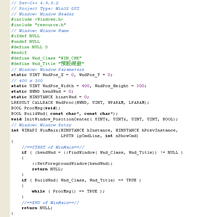

- All robots contain some level of computer programming code. A program is how a robot decides when or how to do something. In the caterpillar track example, a robot that needs to move across a muddy road may have the correct mechanical construction and receive the correct amount of power from its battery, but would not go anywhere without a program telling it to move. Programs are the core essence of a robot, it could have excellent mechanical and electrical construction, but if its program is poorly constructed its performance will be very poor (or it may not perform at all). There are three different types of robotic programs: remote control, artificial intelligence and hybrid. A robot with remote control programing has a preexisting set of commands that it will only perform if and when it receives a signal from a control source, typically a human being with a remote control. It is perhaps more appropriate to view devices controlled primarily by human commands as falling in the discipline of automation rather than robotics. Robots that use artificial intelligence interact with their environment on their own without a control source, and can determine reactions to objects and problems they encounter using their preexisting programming. Hybrid is a form of programming that incorporates both AI and RC functions in them.

Applications

As more and more robots are designed for specific tasks this method of classification becomes more relevant. For example, many robots are designed for assembly work, which may not be readily adaptable for other applications. They are termed as "assembly robots". For seam welding, some suppliers provide complete welding systems with the robot i.e. the welding equipment along with other material handling facilities like turntables, etc. as an integrated unit. Such an integrated robotic system is called a "welding robot" even though its discrete manipulator unit could be adapted to a variety of tasks. Some robots are specifically designed for heavy load manipulation, and are labeled as "heavy-duty robots".[23]

Current and potential applications include:

- Military robots.

- Industrial robots. Robots are increasingly used in manufacturing (since the 1960s). According to the Robotic Industries Association US data, in 2016 automotive industry was the main customer of industrial robots with 52% of total sales.[25] In the auto industry, they can amount for more than half of the "labor". There are even "lights off" factories such as an IBM keyboard manufacturing factory in Texas that was fully automated as early as 2003.[26]

- Cobots (collaborative robots).[27]

- Construction robots. Construction robots can be separated into three types: traditional robots, robotic arm, and robotic exoskeleton.[28]

- Agricultural robots (AgRobots).[29] The use of robots in agriculture is closely linked to the concept of AI-assisted precision agriculture and drone usage.[30] 1996-1998 research also proved that robots can perform a herding task.[31]

- Medical robots of various types (such as da Vinci Surgical System and Hospi).

- Kitchen automation. Commercial examples of kitchen automation are Flippy (burgers), Zume Pizza (pizza), Cafe X (coffee), Makr Shakr (cocktails), Frobot (frozen yogurts) and Sally (salads).[32] Home examples are Rotimatic (flatbreads baking)[33] and Boris (dishwasher loading).[34]

- Robot combat for sport – hobby or sport event where two or more robots fight in an arena to disable each other. This has developed from a hobby in the 1990s to several TV series worldwide.

- Cleanup of contaminated areas, such as toxic waste or nuclear facilities.[35]

- Domestic robots.

- Nanorobots.

- Swarm robotics.[36]

- Autonomous drones.

- Sports field line marking.

Components

Power source

At present, mostly (lead–acid) batteries are used as a power source. Many different types of batteries can be used as a power source for robots. They range from lead–acid batteries, which are safe and have relatively long shelf lives but are rather heavy compared to silver–cadmium batteries that are much smaller in volume and are currently much more expensive. Designing a battery-powered robot needs to take into account factors such as safety, cycle lifetime and weight. Generators, often some type of internal combustion engine, can also be used. However, such designs are often mechanically complex and need a fuel, require heat dissipation and are relatively heavy. A tether connecting the robot to a power supply would remove the power supply from the robot entirely. This has the advantage of saving weight and space by moving all power generation and storage components elsewhere. However, this design does come with the drawback of constantly having a cable connected to the robot, which can be difficult to manage.[37] Potential power sources could be:

- pneumatic (compressed gases)

- Solar power (using the sun's energy and converting it into electrical power)

- hydraulics (liquids)

- flywheel energy storage

- organic garbage (through anaerobic digestion)

- nuclear

Actuation

Actuators are the "muscles" of a robot, the parts which convert stored energy into movement.[38] By far the most popular actuators are electric motors that rotate a wheel or gear, and linear actuators that control industrial robots in factories. There are some recent advances in alternative types of actuators, powered by electricity, chemicals, or compressed air.

Electric motors

The vast majority of robots use electric motors, often brushed and brushless DC motors in portable robots or AC motors in industrial robots and CNC machines. These motors are often preferred in systems with lighter loads, and where the predominant form of motion is rotational.

Linear actuators

Various types of linear actuators move in and out instead of by spinning, and often have quicker direction changes, particularly when very large forces are needed such as with industrial robotics. They are typically powered by compressed and oxidized air (pneumatic actuator) or an oil (hydraulic actuator) Linear actuators can also be powered by electricity which usually consists of a motor and a leadscrew. Another common type is a mechanical linear actuator that is turned by hand, such as a rack and pinion on a car.

Series elastic actuators

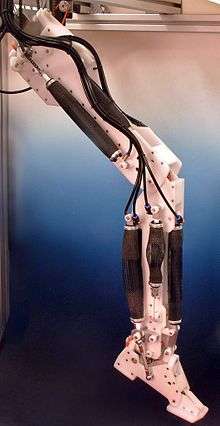

A flexure is designed as part of the motor actuator, to improve safety and provide robust force control, energy efficiency, shock absorption (mechanical filtering) while reducing excessive wear on the transmission and other mechanical components. The resultant lower reflected inertia can improve safety when a robot is interacting with humans or during collisions. It has been used in various robots, particularly advanced manufacturing robots [39] and walking humanoid robots.[40][41]

Air muscles

Pneumatic artificial muscles, also known as air muscles, are special tubes that expand(typically up to 40%) when air is forced inside them. They are used in some robot applications.[42][43][44]

Muscle wire

Muscle wire, also known as shape memory alloy, Nitinol® or Flexinol® wire, is a material which contracts (under 5%) when electricity is applied. They have been used for some small robot applications.[45][46]

Electroactive polymers

EAPs or EPAMs are a plastic material that can contract substantially (up to 380% activation strain) from electricity, and have been used in facial muscles and arms of humanoid robots,[47] and to enable new robots to float,[48] fly, swim or walk.[49]

Piezo motors

Recent alternatives to DC motors are piezo motors or ultrasonic motors. These work on a fundamentally different principle, whereby tiny piezoceramic elements, vibrating many thousands of times per second, cause linear or rotary motion. There are different mechanisms of operation; one type uses the vibration of the piezo elements to step the motor in a circle or a straight line.[50] Another type uses the piezo elements to cause a nut to vibrate or to drive a screw. The advantages of these motors are nanometer resolution, speed, and available force for their size.[51] These motors are already available commercially, and being used on some robots.[52][53]

Elastic nanotubes

Elastic nanotubes are a promising artificial muscle technology in early-stage experimental development. The absence of defects in carbon nanotubes enables these filaments to deform elastically by several percent, with energy storage levels of perhaps 10 J/cm3 for metal nanotubes. Human biceps could be replaced with an 8 mm diameter wire of this material. Such compact "muscle" might allow future robots to outrun and outjump humans.[54]

Sensing

Sensors allow robots to receive information about a certain measurement of the environment, or internal components. This is essential for robots to perform their tasks, and act upon any changes in the environment to calculate the appropriate response. They are used for various forms of measurements, to give the robots warnings about safety or malfunctions, and to provide real-time information of the task it is performing.

Touch

Current robotic and prosthetic hands receive far less tactile information than the human hand. Recent research has developed a tactile sensor array that mimics the mechanical properties and touch receptors of human fingertips.[55][56] The sensor array is constructed as a rigid core surrounded by conductive fluid contained by an elastomeric skin. Electrodes are mounted on the surface of the rigid core and are connected to an impedance-measuring device within the core. When the artificial skin touches an object the fluid path around the electrodes is deformed, producing impedance changes that map the forces received from the object. The researchers expect that an important function of such artificial fingertips will be adjusting robotic grip on held objects.

Scientists from several European countries and Israel developed a prosthetic hand in 2009, called SmartHand, which functions like a real one—allowing patients to write with it, type on a keyboard, play piano and perform other fine movements. The prosthesis has sensors which enable the patient to sense real feeling in its fingertips.[57]

Vision

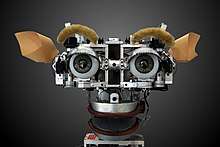

Computer vision is the science and technology of machines that see. As a scientific discipline, computer vision is concerned with the theory behind artificial systems that extract information from images. The image data can take many forms, such as video sequences and views from cameras.

In most practical computer vision applications, the computers are pre-programmed to solve a particular task, but methods based on learning are now becoming increasingly common.

Computer vision systems rely on image sensors which detect electromagnetic radiation which is typically in the form of either visible light or infra-red light. The sensors are designed using solid-state physics. The process by which light propagates and reflects off surfaces is explained using optics. Sophisticated image sensors even require quantum mechanics to provide a complete understanding of the image formation process. Robots can also be equipped with multiple vision sensors to be better able to compute the sense of depth in the environment. Like human eyes, robots' "eyes" must also be able to focus on a particular area of interest, and also adjust to variations in light intensities.

There is a subfield within computer vision where artificial systems are designed to mimic the processing and behavior of biological system, at different levels of complexity. Also, some of the learning-based methods developed within computer vision have their background in biology.

Other

Other common forms of sensing in robotics use lidar, radar, and sonar.[58] Lidar measures distance to a target by illuminating the target with laser light and measuring the reflected light with a sensor. Radar uses radio waves to determine the range, angle, or velocity of objects. Sonar uses sound propagation to navigate, communicate with or detect objects on or under the surface of the water.

Manipulation

.jpg)

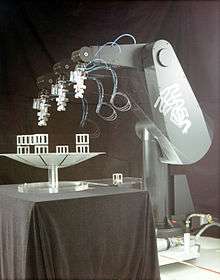

A definition of robotic manipulation has been provided by Matt Mason as: "manipulation refers to an agent’s control of its environment through selective contact”.[59]

Robots need to manipulate objects; pick up, modify, destroy, or otherwise have an effect. Thus the functional end of a robot arm intended to make the effect (whether a hand, or tool) are often referred to as end effectors,[60] while the "arm" is referred to as a manipulator.[61] Most robot arms have replaceable end-effectors, each allowing them to perform some small range of tasks. Some have a fixed manipulator which cannot be replaced, while a few have one very general purpose manipulator, for example, a humanoid hand.[62]

Mechanical grippers

One of the most common types of end-effectors are "grippers". In its simplest manifestation, it consists of just two fingers which can open and close to pick up and let go of a range of small objects. Fingers can for example, be made of a chain with a metal wire run through it.[63] Hands that resemble and work more like a human hand include the Shadow Hand and the Robonaut hand.[64] Hands that are of a mid-level complexity include the Delft hand.[65][66] Mechanical grippers can come in various types, including friction and encompassing jaws. Friction jaws use all the force of the gripper to hold the object in place using friction. Encompassing jaws cradle the object in place, using less friction.

Suction end-effectors

Suction end-effectors, powered by vacuum generators, are very simple astrictive[67] devices that can hold very large loads provided the prehension surface is smooth enough to ensure suction.

Pick and place robots for electronic components and for large objects like car windscreens, often use very simple vacuum end-effectors.

Suction is a highly used type of end-effector in industry, in part because the natural compliance of soft suction end-effectors can enable a robot to be more robust in the presence of imperfect robotic perception. As an example: consider the case of a robot vision system estimates the position of a water bottle, but has 1 centimeter of error. While this may cause a rigid mechanical gripper to puncture the water bottle, the soft suction end-effector may just bend slightly and conform to the shape of the water bottle surface.

General purpose effectors

Some advanced robots are beginning to use fully humanoid hands, like the Shadow Hand, MANUS,[68] and the Schunk hand.[69] These are highly dexterous manipulators, with as many as 20 degrees of freedom and hundreds of tactile sensors.[70]

Locomotion

Rolling robots

For simplicity, most mobile robots have four wheels or a number of continuous tracks. Some researchers have tried to create more complex wheeled robots with only one or two wheels. These can have certain advantages such as greater efficiency and reduced parts, as well as allowing a robot to navigate in confined places that a four-wheeled robot would not be able to.

Two-wheeled balancing robots

Balancing robots generally use a gyroscope to detect how much a robot is falling and then drive the wheels proportionally in the same direction, to counterbalance the fall at hundreds of times per second, based on the dynamics of an inverted pendulum.[71] Many different balancing robots have been designed.[72] While the Segway is not commonly thought of as a robot, it can be thought of as a component of a robot, when used as such Segway refer to them as RMP (Robotic Mobility Platform). An example of this use has been as NASA's Robonaut that has been mounted on a Segway.[73]

One-wheeled balancing robots

A one-wheeled balancing robot is an extension of a two-wheeled balancing robot so that it can move in any 2D direction using a round ball as its only wheel. Several one-wheeled balancing robots have been designed recently, such as Carnegie Mellon University's "Ballbot" that is the approximate height and width of a person, and Tohoku Gakuin University's "BallIP".[74] Because of the long, thin shape and ability to maneuver in tight spaces, they have the potential to function better than other robots in environments with people.[75]

Spherical orb robots

Several attempts have been made in robots that are completely inside a spherical ball, either by spinning a weight inside the ball,[76][77] or by rotating the outer shells of the sphere.[78][79] These have also been referred to as an orb bot[80] or a ball bot.[81][82]

Six-wheeled robots

Using six wheels instead of four wheels can give better traction or grip in outdoor terrain such as on rocky dirt or grass.

Tracked robots

Tank tracks provide even more traction than a six-wheeled robot. Tracked wheels behave as if they were made of hundreds of wheels, therefore are very common for outdoor and military robots, where the robot must drive on very rough terrain. However, they are difficult to use indoors such as on carpets and smooth floors. Examples include NASA's Urban Robot "Urbie".[83]

Walking applied to robots

Walking is a difficult and dynamic problem to solve. Several robots have been made which can walk reliably on two legs, however, none have yet been made which are as robust as a human. There has been much study on human inspired walking, such as AMBER lab which was established in 2008 by the Mechanical Engineering Department at Texas A&M University.[84] Many other robots have been built that walk on more than two legs, due to these robots being significantly easier to construct.[85][86] Walking robots can be used for uneven terrains, which would provide better mobility and energy efficiency than other locomotion methods. Typically, robots on two legs can walk well on flat floors and can occasionally walk up stairs. None can walk over rocky, uneven terrain. Some of the methods which have been tried are:

ZMP technique

The zero moment point (ZMP) is the algorithm used by robots such as Honda's ASIMO. The robot's onboard computer tries to keep the total inertial forces (the combination of Earth's gravity and the acceleration and deceleration of walking), exactly opposed by the floor reaction force (the force of the floor pushing back on the robot's foot). In this way, the two forces cancel out, leaving no moment (force causing the robot to rotate and fall over).[87] However, this is not exactly how a human walks, and the difference is obvious to human observers, some of whom have pointed out that ASIMO walks as if it needs the lavatory.[88][89][90] ASIMO's walking algorithm is not static, and some dynamic balancing is used (see below). However, it still requires a smooth surface to walk on.

Hopping

Several robots, built in the 1980s by Marc Raibert at the MIT Leg Laboratory, successfully demonstrated very dynamic walking. Initially, a robot with only one leg, and a very small foot could stay upright simply by hopping. The movement is the same as that of a person on a pogo stick. As the robot falls to one side, it would jump slightly in that direction, in order to catch itself.[91] Soon, the algorithm was generalised to two and four legs. A bipedal robot was demonstrated running and even performing somersaults.[92] A quadruped was also demonstrated which could trot, run, pace, and bound.[93] For a full list of these robots, see the MIT Leg Lab Robots page.[94]

Dynamic balancing (controlled falling)

A more advanced way for a robot to walk is by using a dynamic balancing algorithm, which is potentially more robust than the Zero Moment Point technique, as it constantly monitors the robot's motion, and places the feet in order to maintain stability.[95] This technique was recently demonstrated by Anybots' Dexter Robot,[96] which is so stable, it can even jump.[97] Another example is the TU Delft Flame.

Passive dynamics

Perhaps the most promising approach utilizes passive dynamics where the momentum of swinging limbs is used for greater efficiency. It has been shown that totally unpowered humanoid mechanisms can walk down a gentle slope, using only gravity to propel themselves. Using this technique, a robot need only supply a small amount of motor power to walk along a flat surface or a little more to walk up a hill. This technique promises to make walking robots at least ten times more efficient than ZMP walkers, like ASIMO.[98][99]

Other methods of locomotion

Flying

A modern passenger airliner is essentially a flying robot, with two humans to manage it. The autopilot can control the plane for each stage of the journey, including takeoff, normal flight, and even landing.[100] Other flying robots are uninhabited and are known as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). They can be smaller and lighter without a human pilot on board, and fly into dangerous territory for military surveillance missions. Some can even fire on targets under command. UAVs are also being developed which can fire on targets automatically, without the need for a command from a human. Other flying robots include cruise missiles, the Entomopter, and the Epson micro helicopter robot. Robots such as the Air Penguin, Air Ray, and Air Jelly have lighter-than-air bodies, propelled by paddles, and guided by sonar.

Snaking

Several snake robots have been successfully developed. Mimicking the way real snakes move, these robots can navigate very confined spaces, meaning they may one day be used to search for people trapped in collapsed buildings.[101] The Japanese ACM-R5 snake robot[102] can even navigate both on land and in water.[103]

Skating

A small number of skating robots have been developed, one of which is a multi-mode walking and skating device. It has four legs, with unpowered wheels, which can either step or roll.[104] Another robot, Plen, can use a miniature skateboard or roller-skates, and skate across a desktop.[105]

Climbing

Several different approaches have been used to develop robots that have the ability to climb vertical surfaces. One approach mimics the movements of a human climber on a wall with protrusions; adjusting the center of mass and moving each limb in turn to gain leverage. An example of this is Capuchin,[106] built by Dr. Ruixiang Zhang at Stanford University, California. Another approach uses the specialized toe pad method of wall-climbing geckoes, which can run on smooth surfaces such as vertical glass. Examples of this approach include Wallbot[107] and Stickybot.[108]

China's Technology Daily reported on 15 November 2008, that Dr. Li Hiu Yeung and his research group of New Concept Aircraft (Zhuhai) Co., Ltd. had successfully developed a bionic gecko robot named "Speedy Freelander". According to Dr. Yeung, the gecko robot could rapidly climb up and down a variety of building walls, navigate through ground and wall fissures, and walk upside-down on the ceiling. It was also able to adapt to the surfaces of smooth glass, rough, sticky or dusty walls as well as various types of metallic materials. It could also identify and circumvent obstacles automatically. Its flexibility and speed were comparable to a natural gecko. A third approach is to mimic the motion of a snake climbing a pole.[58]

Swimming (Piscine)

It is calculated that when swimming some fish can achieve a propulsive efficiency greater than 90%.[109] Furthermore, they can accelerate and maneuver far better than any man-made boat or submarine, and produce less noise and water disturbance. Therefore, many researchers studying underwater robots would like to copy this type of locomotion.[110] Notable examples are the Essex University Computer Science Robotic Fish G9,[111] and the Robot Tuna built by the Institute of Field Robotics, to analyze and mathematically model thunniform motion.[112] The Aqua Penguin,[113] designed and built by Festo of Germany, copies the streamlined shape and propulsion by front "flippers" of penguins. Festo have also built the Aqua Ray and Aqua Jelly, which emulate the locomotion of manta ray, and jellyfish, respectively.

In 2014 iSplash-II was developed by PhD student Richard James Clapham and Prof. Huosheng Hu at Essex University. It was the first robotic fish capable of outperforming real carangiform fish in terms of average maximum velocity (measured in body lengths/ second) and endurance, the duration that top speed is maintained.[114] This build attained swimming speeds of 11.6BL/s (i.e. 3.7 m/s).[115] The first build, iSplash-I (2014) was the first robotic platform to apply a full-body length carangiform swimming motion which was found to increase swimming speed by 27% over the traditional approach of a posterior confined waveform.[116]

Sailing

Sailboat robots have also been developed in order to make measurements at the surface of the ocean. A typical sailboat robot is Vaimos[117] built by IFREMER and ENSTA-Bretagne. Since the propulsion of sailboat robots uses the wind, the energy of the batteries is only used for the computer, for the communication and for the actuators (to tune the rudder and the sail). If the robot is equipped with solar panels, the robot could theoretically navigate forever. The two main competitions of sailboat robots are WRSC, which takes place every year in Europe, and Sailbot.

Environmental interaction and navigation

Though a significant percentage of robots in commission today are either human controlled or operate in a static environment, there is an increasing interest in robots that can operate autonomously in a dynamic environment. These robots require some combination of navigation hardware and software in order to traverse their environment. In particular, unforeseen events (e.g. people and other obstacles that are not stationary) can cause problems or collisions. Some highly advanced robots such as ASIMO and Meinü robot have particularly good robot navigation hardware and software. Also, self-controlled cars, Ernst Dickmanns' driverless car, and the entries in the DARPA Grand Challenge, are capable of sensing the environment well and subsequently making navigational decisions based on this information, including by a swarm of autonomous robots.[36] Most of these robots employ a GPS navigation device with waypoints, along with radar, sometimes combined with other sensory data such as lidar, video cameras, and inertial guidance systems for better navigation between waypoints.

Human-robot interaction

The state of the art in sensory intelligence for robots will have to progress through several orders of magnitude if we want the robots working in our homes to go beyond vacuum-cleaning the floors. If robots are to work effectively in homes and other non-industrial environments, the way they are instructed to perform their jobs, and especially how they will be told to stop will be of critical importance. The people who interact with them may have little or no training in robotics, and so any interface will need to be extremely intuitive. Science fiction authors also typically assume that robots will eventually be capable of communicating with humans through speech, gestures, and facial expressions, rather than a command-line interface. Although speech would be the most natural way for the human to communicate, it is unnatural for the robot. It will probably be a long time before robots interact as naturally as the fictional C-3PO, or Data of Star Trek, Next Generation.

Speech recognition

Interpreting the continuous flow of sounds coming from a human, in real time, is a difficult task for a computer, mostly because of the great variability of speech.[118] The same word, spoken by the same person may sound different depending on local acoustics, volume, the previous word, whether or not the speaker has a cold, etc.. It becomes even harder when the speaker has a different accent.[119] Nevertheless, great strides have been made in the field since Davis, Biddulph, and Balashek designed the first "voice input system" which recognized "ten digits spoken by a single user with 100% accuracy" in 1952.[120] Currently, the best systems can recognize continuous, natural speech, up to 160 words per minute, with an accuracy of 95%.[121] With the help of artificial intelligence, machines nowadays can use people's voice to identify their emotions such as satisfied or angry[122]

Robotic voice

Other hurdles exist when allowing the robot to use voice for interacting with humans. For social reasons, synthetic voice proves suboptimal as a communication medium,[123] making it necessary to develop the emotional component of robotic voice through various techniques.[124][125] An advantage of diphonic branching is the emotion that the robot is programmed to project, can be carried on the voice tape, or phoneme, already pre-programmed onto the voice media. One of the earliest examples is a teaching robot named leachim developed in 1974 by Michael J. Freeman.[126][127] Leachim was able to convert digital memory to rudimentary verbal speech on pre-recorded computer discs.[128] It was programmed to teach students in The Bronx, New York.[128]

Gestures

One can imagine, in the future, explaining to a robot chef how to make a pastry, or asking directions from a robot police officer. In both of these cases, making hand gestures would aid the verbal descriptions. In the first case, the robot would be recognizing gestures made by the human, and perhaps repeating them for confirmation. In the second case, the robot police officer would gesture to indicate "down the road, then turn right". It is likely that gestures will make up a part of the interaction between humans and robots.[129] A great many systems have been developed to recognize human hand gestures.[130]

Facial expression

Facial expressions can provide rapid feedback on the progress of a dialog between two humans, and soon may be able to do the same for humans and robots. Robotic faces have been constructed by Hanson Robotics using their elastic polymer called Frubber, allowing a large number of facial expressions due to the elasticity of the rubber facial coating and embedded subsurface motors (servos).[131] The coating and servos are built on a metal skull. A robot should know how to approach a human, judging by their facial expression and body language. Whether the person is happy, frightened, or crazy-looking affects the type of interaction expected of the robot. Likewise, robots like Kismet and the more recent addition, Nexi[132] can produce a range of facial expressions, allowing it to have meaningful social exchanges with humans.[133]

Artificial emotions

Artificial emotions can also be generated, composed of a sequence of facial expressions and/or gestures. As can be seen from the movie Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, the programming of these artificial emotions is complex and requires a large amount of human observation. To simplify this programming in the movie, presets were created together with a special software program. This decreased the amount of time needed to make the film. These presets could possibly be transferred for use in real-life robots.

Personality

Many of the robots of science fiction have a personality, something which may or may not be desirable in the commercial robots of the future.[134] Nevertheless, researchers are trying to create robots which appear to have a personality:[135][136] i.e. they use sounds, facial expressions, and body language to try to convey an internal state, which may be joy, sadness, or fear. One commercial example is Pleo, a toy robot dinosaur, which can exhibit several apparent emotions.[137]

Social Intelligence

The Socially Intelligent Machines Lab of the Georgia Institute of Technology researches new concepts of guided teaching interaction with robots. The aim of the projects is a social robot that learns task and goals from human demonstrations without prior knowledge of high-level concepts. These new concepts are grounded from low-level continuous sensor data through unsupervised learning, and task goals are subsequently learned using a Bayesian approach. These concepts can be used to transfer knowledge to future tasks, resulting in faster learning of those tasks. The results are demonstrated by the robot Curi who can scoop some pasta from a pot onto a plate and serve the sauce on top.[138]

Control

The mechanical structure of a robot must be controlled to perform tasks. The control of a robot involves three distinct phases – perception, processing, and action (robotic paradigms). Sensors give information about the environment or the robot itself (e.g. the position of its joints or its end effector). This information is then processed to be stored or transmitted and to calculate the appropriate signals to the actuators (motors) which move the mechanical.

The processing phase can range in complexity. At a reactive level, it may translate raw sensor information directly into actuator commands. Sensor fusion may first be used to estimate parameters of interest (e.g. the position of the robot's gripper) from noisy sensor data. An immediate task (such as moving the gripper in a certain direction) is inferred from these estimates. Techniques from control theory convert the task into commands that drive the actuators.

At longer time scales or with more sophisticated tasks, the robot may need to build and reason with a "cognitive" model. Cognitive models try to represent the robot, the world, and how they interact. Pattern recognition and computer vision can be used to track objects. Mapping techniques can be used to build maps of the world. Finally, motion planning and other artificial intelligence techniques may be used to figure out how to act. For example, a planner may figure out how to achieve a task without hitting obstacles, falling over, etc.

Autonomy levels

Control systems may also have varying levels of autonomy.

- Direct interaction is used for haptic or teleoperated devices, and the human has nearly complete control over the robot's motion.

- Operator-assist modes have the operator commanding medium-to-high-level tasks, with the robot automatically figuring out how to achieve them.[140]

- An autonomous robot may go without human interaction for extended periods of time . Higher levels of autonomy do not necessarily require more complex cognitive capabilities. For example, robots in assembly plants are completely autonomous but operate in a fixed pattern.

Another classification takes into account the interaction between human control and the machine motions.

- Teleoperation. A human controls each movement, each machine actuator change is specified by the operator.

- Supervisory. A human specifies general moves or position changes and the machine decides specific movements of its actuators.

- Task-level autonomy. The operator specifies only the task and the robot manages itself to complete it.

- Full autonomy. The machine will create and complete all its tasks without human interaction.

Research

Much of the research in robotics focuses not on specific industrial tasks, but on investigations into new types of robots, alternative ways to think about or design robots, and new ways to manufacture them. Other investigations, such as MIT's cyberflora project, are almost wholly academic.

A first particular new innovation in robot design is the open sourcing of robot-projects. To describe the level of advancement of a robot, the term "Generation Robots" can be used. This term is coined by Professor Hans Moravec, Principal Research Scientist at the Carnegie Mellon University Robotics Institute in describing the near future evolution of robot technology. First generation robots, Moravec predicted in 1997, should have an intellectual capacity comparable to perhaps a lizard and should become available by 2010. Because the first generation robot would be incapable of learning, however, Moravec predicts that the second generation robot would be an improvement over the first and become available by 2020, with the intelligence maybe comparable to that of a mouse. The third generation robot should have the intelligence comparable to that of a monkey. Though fourth generation robots, robots with human intelligence, professor Moravec predicts, would become possible, he does not predict this happening before around 2040 or 2050.[141]

The second is evolutionary robots. This is a methodology that uses evolutionary computation to help design robots, especially the body form, or motion and behavior controllers. In a similar way to natural evolution, a large population of robots is allowed to compete in some way, or their ability to perform a task is measured using a fitness function. Those that perform worst are removed from the population and replaced by a new set, which have new behaviors based on those of the winners. Over time the population improves, and eventually a satisfactory robot may appear. This happens without any direct programming of the robots by the researchers. Researchers use this method both to create better robots,[142] and to explore the nature of evolution.[143] Because the process often requires many generations of robots to be simulated,[144] this technique may be run entirely or mostly in simulation, using a robot simulator software package, then tested on real robots once the evolved algorithms are good enough.[145] Currently, there are about 10 million industrial robots toiling around the world, and Japan is the top country having high density of utilizing robots in its manufacturing industry.

Dynamics and kinematics

The study of motion can be divided into kinematics and dynamics.[146] Direct kinematics or forward kinematics refers to the calculation of end effector position, orientation, velocity, and acceleration when the corresponding joint values are known. Inverse kinematics refers to the opposite case in which required joint values are calculated for given end effector values, as done in path planning. Some special aspects of kinematics include handling of redundancy (different possibilities of performing the same movement), collision avoidance, and singularity avoidance. Once all relevant positions, velocities, and accelerations have been calculated using kinematics, methods from the field of dynamics are used to study the effect of forces upon these movements. Direct dynamics refers to the calculation of accelerations in the robot once the applied forces are known. Direct dynamics is used in computer simulations of the robot. Inverse dynamics refers to the calculation of the actuator forces necessary to create a prescribed end-effector acceleration. This information can be used to improve the control algorithms of a robot.

In each area mentioned above, researchers strive to develop new concepts and strategies, improve existing ones, and improve the interaction between these areas. To do this, criteria for "optimal" performance and ways to optimize design, structure, and control of robots must be developed and implemented.

Bionics and biomimetics

Bionics and biomimetics apply the physiology and methods of locomotion of animals to the design of robots. For example, the design of BionicKangaroo was based on the way kangaroos jump.

Quantum computing

There has been some research into whether robotics algorithms can be run more quickly on quantum computers than they can be run on digital computers. This area has been referred to as quantum robotics.[147]

Education and training

Robotics engineers design robots, maintain them, develop new applications for them, and conduct research to expand the potential of robotics.[148] Robots have become a popular educational tool in some middle and high schools, particularly in parts of the USA,[149] as well as in numerous youth summer camps, raising interest in programming, artificial intelligence, and robotics among students.

Career training

Universities like Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) offer bachelors, masters, and doctoral degrees in the field of robotics.[150] Vocational schools offer robotics training aimed at careers in robotics.

Certification

The Robotics Certification Standards Alliance (RCSA) is an international robotics certification authority that confers various industry- and educational-related robotics certifications.

Summer robotics camp

Several national summer camp programs include robotics as part of their core curriculum. In addition, youth summer robotics programs are frequently offered by celebrated museums and institutions.

Robotics competitions

There are many competitions around the globe. The SeaPerch curriculum is aimed as students of all ages. This is a short list of competition examples; for a more complete list see Robot competition.

Competitions for Younger Children

The FIRST organization offers the FIRST Lego League Jr. competitions for younger children. This competition's goal is to offer younger children an opportunity to start learning about science and technology. Children in this competition build Lego models and have the option of using the Lego WeDo robotics kit.

Competitions for Children Ages 9-14

One of the most important competitions is the FLL or FIRST Lego League. The idea of this specific competition is that kids start developing knowledge and getting into robotics while playing with Lego since they are nine years old. This competition is associated with National Instruments. Children use Lego Mindstorms to solve autonomous robotics challenges in this competition.

Competitions for Teenagers

The FIRST Tech Challenge is designed for intermediate students, as a transition from the FIRST Lego League to the FIRST Robotics Competition.

The FIRST Robotics Competition focuses more on mechanical design, with a specific game being played each year. Robots are built specifically for that year's game. In match play, the robot moves autonomously during the first 15 seconds of the game (although certain years such as 2019's Deep Space change this rule), and is manually operated for the rest of the match.

Competitions for Older Students

The various RoboCup competitions include teams of teenagers and university students. These competitions focus on soccer competitions with different types of robots, dance competitions, and urban search and rescue competitions. All of the robots in these competitions must be autonomous. Some of these competitions focus on simulated robots.

AUVSI runs competitions for flying robots, robot boats, and underwater robots.

The Student AUV Competition Europe [151] (SAUC-E) mainly attracts undergraduate and graduate student teams. As in the AUVSI competitions, the robots must be fully autonomous while they are participating in the competition.

The Microtransat Challenge is a competition to sail a boat across the Atlantic Ocean.

Competitions Open to Anyone

RoboGames is open to anyone wishing to compete in their over 50 categories of robot competitions.

Federation of International Robot-soccer Association holds the FIRA World Cup competitions. There are flying robot competitions, robot soccer competitions, and other challenges, including weightlifting barbells made from dowels and CDs.

Robotics afterschool programs

Many schools across the country are beginning to add robotics programs to their after school curriculum. Some major programs for afterschool robotics include FIRST Robotics Competition, Botball and B.E.S.T. Robotics.[152] Robotics competitions often include aspects of business and marketing as well as engineering and design.

The Lego company began a program for children to learn and get excited about robotics at a young age.[153]

Decolonial Educational Robotics

Decolonial Educational Robotics is a branch of Decolonial Technology, and Decolonial A.I.[154], practiced in various places around the world. This methodology is summarized in pedagogical theories and practices such as Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Montessori methods. And it aims at teaching robotics from the local culture, to pluralize and mix technological knowledge.[155]

Employment

Robotics is an essential component in many modern manufacturing environments. As factories increase their use of robots, the number of robotics–related jobs grow and have been observed to be steadily rising.[156] The employment of robots in industries has increased productivity and efficiency savings and is typically seen as a long term investment for benefactors. A paper by Michael Osborne and Carl Benedikt Frey found that 47 per cent of US jobs are at risk to automation "over some unspecified number of years".[157] These claims have been criticized on the ground that social policy, not AI, causes unemployment.[158] In a 2016 article in The Guardian, Stephen Hawking stated "The automation of factories has already decimated jobs in traditional manufacturing, and the rise of artificial intelligence is likely to extend this job destruction deep into the middle classes, with only the most caring, creative or supervisory roles remaining".[159]

Occupational safety and health implications

A discussion paper drawn up by EU-OSHA highlights how the spread of robotics presents both opportunities and challenges for occupational safety and health (OSH).[160]

The greatest OSH benefits stemming from the wider use of robotics should be substitution for people working in unhealthy or dangerous environments. In space, defence, security, or the nuclear industry, but also in logistics, maintenance, and inspection, autonomous robots are particularly useful in replacing human workers performing dirty, dull or unsafe tasks, thus avoiding workers' exposures to hazardous agents and conditions and reducing physical, ergonomic and psychosocial risks. For example, robots are already used to perform repetitive and monotonous tasks, to handle radioactive material or to work in explosive atmospheres. In the future, many other highly repetitive, risky or unpleasant tasks will be performed by robots in a variety of sectors like agriculture, construction, transport, healthcare, firefighting or cleaning services.[161]

Despite these advances, there are certain skills to which humans will be better suited than machines for some time to come and the question is how to achieve the best combination of human and robot skills. The advantages of robotics include heavy-duty jobs with precision and repeatability, whereas the advantages of humans include creativity, decision-making, flexibility, and adaptability. This need to combine optimal skills has resulted in collaborative robots and humans sharing a common workspace more closely and led to the development of new approaches and standards to guarantee the safety of the "man-robot merger". Some European countries are including robotics in their national programmes and trying to promote a safe and flexible co-operation between robots and operators to achieve better productivity. For example, the German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA) organises annual workshops on the topic "human-robot collaboration".

In the future, co-operation between robots and humans will be diversified, with robots increasing their autonomy and human-robot collaboration reaching completely new forms. Current approaches and technical standards[162][163] aiming to protect employees from the risk of working with collaborative robots will have to be revised.

See also

References

- International classification system of the German National Library (GND) https://portal.dnb.de/opac.htm?method=simpleSearch&cqlMode=true&query=nid%3D4261462-4. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Nocks, Lisa (2007). The robot : the life story of a technology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Arreguin, Juan (2008). Automation and Robotics. Vienna, Austria: I-Tech and Publishing.

- Zunt, Dominik. "Who did actually invent the word "robot" and what does it mean?". The Karel Čapek website. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Asimov, Isaac (1996) [1995]. "The Robot Chronicles". Gold. London: Voyager. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0-00-648202-4.

- Asimov, Isaac (1983). "4 The Word I Invented". Counting the Eons. Doubleday. Bibcode:1983coeo.book.....A.

Robotics has become a sufficiently well developed technology to warrant articles and books on its history and I have watched this in amazement, and in some disbelief, because I invented … the word

- Svoboda, Elizabeth (25 September 2019). "Your robot surgeon will see you now". Nature. 573: S110–S111. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02874-0.

- "Robotics: About the Exhibition". The Tech Museum of Innovation. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- Needham, Joseph (1991). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 2, History of Scientific Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05800-1.

- Fowler, Charles B. (October 1967). "The Museum of Music: A History of Mechanical Instruments". Music Educators Journal. 54 (2): 45–49. doi:10.2307/3391092. JSTOR 3391092.

- Rosheim, Mark E. (1994). Robot Evolution: The Development of Anthrobotics. Wiley-IEEE. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-471-02622-8.

- al-Jazari (Islamic artist), Encyclopædia Britannica.

- PhD, Renato M.E. Sabbatini. "Sabbatini, RME: An Imitation of Life: The First Robots".

- Waurzyniak, Patrick (2006). "Masters of Manufacturing: Joseph F. Engelberger". Society of Manufacturing Engineers. 137 (1). Archived from the original on 9 November 2011.

- "Humanoid History -WABOT-". www.humanoid.waseda.ac.jp.

- Zeghloul, Saïd; Laribi, Med Amine; Gazeau, Jean-Pierre (21 September 2015). Robotics and Mechatronics: Proceedings of the 4th IFToMM International Symposium on Robotics and Mechatronics. Springer. ISBN 9783319223681 – via Google Books.

- "Historical Android Projects". androidworld.com.

- Robots: From Science Fiction to Technological Revolution, page 130

- Duffy, Vincent G. (19 April 2016). Handbook of Digital Human Modeling: Research for Applied Ergonomics and Human Factors Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420063523 – via Google Books.

- "KUKA Industrial Robot FAMULUS". Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- "History of Industrial Robots" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- S. Bozinovski, Parallel programming for mobile robot control: Agent based approach, Proc IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems, p. 202-208, Poznan, 1994

- Hunt, V. Daniel (1985). "Smart Robots". Smart Robots: A Handbook of Intelligent Robotic Systems. Chapman and Hall. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4613-2533-8.

- "Meet Atlas, the Robot Designed to Save the Day". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- "Robot density rises globally". Robotic Industries Association. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Pinto, Jim (1 October 2003). "Fully automated factories approach reality". Automation World. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Dragani, Rachelle (8 November 2018). "Can a robot make you a 'superworker'?". Verizon Communications. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Pollock, Emily (7 June 2018). "Construction Robotics Industry Set to Double by 2023". engineering.com. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Grift, Tony E. (2004). "Agricultural Robotics". University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Thomas, Jim (1 November 2017). "How corporate giants are automating the farm". New Internationalist. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "OUCL Robot Sheepdog Project". Department of Computer Science, University of Oxford. 3 July 2001. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Kolodny, Lora (4 July 2017). "Robots are coming to a burger joint near you". CNBC. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Corner, Stuart (23 November 2017). "AI-driven robot makes 'perfect' flatbread". iothub.com.au. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Eyre, Michael (12 September 2014). "'Boris' the robot can load up dishwasher". BBC News. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- One database, developed by the United States Department of Energy contains information on almost 500 existing robotic technologies and can be found on the D&D Knowledge Management Information Tool.

- Kagan, Eugene, and Irad Ben-Gal (2015). Search and foraging:individual motion and swarm dynamics. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2015. ISBN 9781482242102.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dowling, Kevin. "Power Sources for Small Robots" (PDF). Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- Roozing, Wesley; Li, Zhibin; Tsagarakis, Nikos; Caldwell, Darwin (2016). "Design Optimisation and Control of Compliant Actuation Arrangements in Articulated Robots for Improved Energy Efficiency". IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters. 1 (2): 1110–1117. doi:10.1109/LRA.2016.2521926.

- Bi-directional series-parallel elastic actuator and overlap of the actuation layers Raphaël Furnémont1, Glenn Mathijssen1,2, Tom Verstraten1, Dirk Lefeber1 and Bram Vanderborght1 Published 26 January 2016 • © 2016 IOP Publishing Ltd

- Pratt, Jerry E.; Krupp, Benjamin T. (2004). "Series Elastic Actuators for legged robots". In Gerhart, Grant R; Shoemaker, Chuck M; Gage, Douglas W (eds.). Unmanned Ground Vehicle Technology VI. Unmanned Ground Vehicle Technology Vi. 5422. pp. 135–144. Bibcode:2004SPIE.5422..135P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.107.349. doi:10.1117/12.548000.

- Li, Zhibin; Tsagarakis, Nikos; Caldwell, Darwin (2013). "Walking Pattern Generation for a Humanoid Robot with Compliant Joints". Autonomous Robots. 35 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/s10514-013-9330-7.

- www.imagesco.com, Images SI Inc -. "Air Muscle actuators, going further, page 6".

- "Air Muscles". Shadow Robot. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Tondu, Bertrand (2012). "Modelling of the McKibben artificial muscle: A review". Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures. 23 (3): 225–253. doi:10.1177/1045389X11435435.

- "TALKING ELECTRONICS Nitinol Page-1". Talkingelectronics.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "lf205, Hardware: Building a Linux-controlled walking robot". Ibiblio.org. 1 November 2001. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "WW-EAP and Artificial Muscles". Eap.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Empa – a117-2-eap". Empa.ch. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Electroactive Polymers (EAP) as Artificial Muscles (EPAM) for Robot Applications". Hizook. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Piezo LEGS – -09-26". Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- "Squiggle Motors: Overview". Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- Nishibori; et al. (2003). "Robot Hand with Fingers Using Vibration-Type Ultrasonic Motors (Driving Characteristics)". Journal of Robotics and Mechatronics. 15 (6): 588–595. doi:10.20965/jrm.2003.p0588.

- Otake; et al. (2001). "Shape Design of Gel Robots made of Electroactive Polymer trolo Gel" (PDF). Retrieved 16 October 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - John D. Madden, 2007, /science.1146351

- "Syntouch LLC: BioTac(R) Biomimetic Tactile Sensor Array". Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- Wettels, N; Santos, VJ; Johansson, RS; Loeb, Gerald E.; et al. (2008). "Biomimetic tactile sensor array". Advanced Robotics. 22 (8): 829–849. doi:10.1163/156855308X314533.

- "What is The SmartHand?". SmartHand Project. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- Arreguin, Juan (2008). Automation and Robotics. Vienna, Austria: I-Tech and Publishing.

- Mason, Matthew T. (2001). "Mechanics of Robotic Manipulation". doi:10.7551/mitpress/4527.001.0001. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "What is a robotic end-effector?". ATI Industrial Automation. 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- Crane, Carl D.; Joseph Duffy (1998). Kinematic Analysis of Robot Manipulators. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57063-3. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- G.J. Monkman, S. Hesse, R. Steinmann & H. Schunk (2007). Robot Grippers. Berlin: Wiley

- "Annotated Mythbusters: Episode 78: Ninja Myths – Walking on Water, Catching a Sword, Catching an Arrow". (Discovery Channel's Mythbusters making mechanical gripper from chain and metal wire)

- Robonaut hand

- "Delft hand". TU Delft. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- M&C. "TU Delft ontwikkelt goedkope, voorzichtige robothand".

- "astrictive definition – English definition dictionary – Reverso".

- Tijsma, H. A.; Liefhebber, F.; Herder, J. L. (1 June 2005). "Evaluation of new user interface features for the MANUS robot arm". 9th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, 2005. ICORR 2005. pp. 258–263. doi:10.1109/ICORR.2005.1501097. ISBN 978-0-7803-9003-4 – via IEEE Xplore.

- Allcock, Andrew (2006). "Anthropomorphic hand is almost human". Machinery. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "Welcome".

- "T.O.B.B". Mtoussaint.de. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "nBot, a two wheel balancing robot". Geology.heroy.smu.edu. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "ROBONAUT Activity Report". NASA. 2004. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- "IEEE Spectrum: A Robot That Balances on a Ball". Spectrum.ieee.org. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Carnegie Mellon Researchers Develop New Type of Mobile Robot That Balances and Moves on a Ball Instead of Legs or Wheels" (Press release). Carnegie Mellon. 9 August 2006. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- "Spherical Robot Can Climb Over Obstacles". BotJunkie. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Rotundus". Rotundus.se. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "OrbSwarm Gets A Brain". BotJunkie. 11 July 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Rolling Orbital Bluetooth Operated Thing". BotJunkie. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Swarm". Orbswarm.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "The Ball Bot : Johnnytronic@Sun". Blogs.sun.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Senior Design Projects | College of Engineering & Applied Science| University of Colorado at Boulder". Engineering.colorado.edu. 30 April 2008. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "JPL Robotics: System: Commercial Rovers".

- "AMBER Lab".

- "Micromagic Systems Robotics Lab".

- "AMRU-5 hexapod robot" (PDF).

- "Achieving Stable Walking". Honda Worldwide. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- "Funny Walk". Pooter Geek. 28 December 2004. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- "ASIMO's Pimp Shuffle". Popular Science. 9 January 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- "The Temple of VTEC – Honda and Acura Enthusiasts Online Forums > Robot Shows Prime Minister How to Loosen Up > > A drunk robot?".

- "3D One-Leg Hopper (1983–1984)". MIT Leg Laboratory. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- "3D Biped (1989–1995)". MIT Leg Laboratory.

- "Quadruped (1984–1987)". MIT Leg Laboratory.

- "MIT Leg Lab Robots- Main".

- "About the robots". Anybots. Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- "Homepage". Anybots. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- "Dexter Jumps video". YouTube. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- Collins, Steve; Wisse, Martijn; Ruina, Andy; Tedrake, Russ (11 February 2005). "Efficient bipedal robots based on passive-dynamic Walkers" (PDF). Science. 307 (5712): 1082–1085. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1082C. doi:10.1126/science.1107799. PMID 15718465. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Collins, Steve; Ruina, Andy. "A bipedal walking robot with efficient and human-like gait" (PDF). Proc. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation.

- "Testing the Limits" (PDF). Boeing. p. 29. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- Miller, Gavin. "Introduction". snakerobots.com. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- "ACM-R5". Archived from the original on 11 October 2011.

- "Swimming snake robot (commentary in Japanese)".

- "Commercialized Quadruped Walking Vehicle "TITAN VII"". Hirose Fukushima Robotics Lab. Archived from the original on 6 November 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- "Plen, the robot that skates across your desk". SCI FI Tech. 23 January 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- Capuchin on YouTube

- Wallbot on YouTube

- Stanford University: Stickybot on YouTube

- Sfakiotakis; et al. (1999). "Review of Fish Swimming Modes for Aquatic Locomotion" (PDF). IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering. 24 (2): 237–252. Bibcode:1999IJOE...24..237S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.8614. doi:10.1109/48.757275. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- Richard Mason. "What is the market for robot fish?". Archived from the original on 4 July 2009.

- "Robotic fish powered by Gumstix PC and PIC". Human Centred Robotics Group at Essex University. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- Witoon Juwarahawong. "Fish Robot". Institute of Field Robotics. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- "YouTube".

- "High-Speed Robotic Fish | iSplash". isplash-robot. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "iSplash-II: Realizing Fast Carangiform Swimming to Outperform a Real Fish" (PDF). Robotics Group at Essex University. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "iSplash-I: High Performance Swimming Motion of a Carangiform Robotic Fish with Full-Body Coordination" (PDF). Robotics Group at Essex University. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Jaulin, L.; Le Bars, F. (2012). "An interval approach for stability analysis; Application to sailboat robotics" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Robotics. 27 (5).

- Pires, J. Norberto (2005). "Robot-by-voice: experiments on commanding an industrial robot using the human voice" (PDF). Industrial Robot: An International Journal. 32 (6): 505–511. doi:10.1108/01439910510629244.

- "Survey of the State of the Art in Human Language Technology: 1.2: Speech Recognition". Archived from the original on 11 November 2007.

- Fournier, Randolph Scott., and B. June. Schmidt. "Voice Input Technology: Learning Style and Attitude Toward Its Use." Delta Pi Epsilon Journal 37 (1995): 1_12.

- "History of Speech & Voice Recognition and Transcription Software". Dragon Naturally Speaking. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Cheng Lin, Kuan; Huang, Tien‐Chi; Hung, Jason C.; Yen, Neil Y.; Ju Chen, Szu (7 June 2013). Chen, Mu‐Yen (ed.). "Facial emotion recognition towards affective computing‐based learning". Library Hi Tech. 31 (2): 294–307. doi:10.1108/07378831311329068. ISSN 0737-8831.

- M.L. Walters, D.S. Syrdal, K.L. Koay, K. Dautenhahn, R. te Boekhorst, (2008). Human approach distances to a mechanical-looking robot with different robot voice styles. In: Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 2008. RO-MAN 2008, Munich, 1–3 Aug 2008, pp. 707–712, doi:10.1109/ROMAN.2008.4600750. Available: online and pdf Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Sandra Pauletto, Tristan Bowles, (2010). Designing the emotional content of a robotic speech signal. In: Proceedings of the 5th Audio Mostly Conference: A Conference on Interaction with Sound, New York, ISBN 978-1-4503-0046-9, doi:10.1145/1859799.1859804. Available: online

- Tristan Bowles, Sandra Pauletto, (2010). Emotions in the Voice: Humanising a Robotic Voice. In: Proceedings of the 7th Sound and Music Computing Conference, Barcelona, Spain.

- "World of 2-XL: Leachim". www.2xlrobot.com. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "The Boston Globe from Boston, Massachusetts on June 23, 1974 · 132". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "cyberneticzoo.com - Page 135 of 194 - a history of cybernetic animals and early robots". cyberneticzoo.com. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Waldherr, Romero & Thrun (2000). "A Gesture Based Interface for Human-Robot Interaction" (PDF). Kluwer Academic Publishers. Retrieved 28 October 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Markus Kohler (2012). "Vision Based Hand Gesture Recognition Systems". Applied Mechanics and Materials. University of Dortmund. 263–266: 2422–2425. Bibcode:2012AMM...263.2422L. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.263-266.2422. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- "Frubber facial expressions". Archived from the original on 7 February 2009.

- "Best Inventions of 2008 – TIME". Time. 29 October 2008 – via www.time.com.

- "Kismet: Robot at MIT's AI Lab Interacts With Humans". Sam Ogden. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- "(Park et al. 2005) Synthetic Personality in Robots and its Effect on Human-Robot Relationship" (PDF).

- "Robot Receptionist Dishes Directions and Attitude".

- "New Scientist: A good robot has personality but not looks" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2006.

- "Playtime with Pleo, your robotic dinosaur friend".

- Jennifer Bogo (31 October 2014). "Meet a woman who trains robots for a living".

- "A Ping-Pong-Playing Terminator". Popular Science.

- "Synthiam Exosphere combines AI, human operators to train robots". The Robot Report.

- NOVA conversation with Professor Moravec, October 1997. NOVA Online

- Sandhana, Lakshmi (5 September 2002). "A Theory of Evolution, for Robots". Wired. Wired Magazine. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- Experimental Evolution In Robots Probes The Emergence Of Biological Communication. Science Daily. 24 February 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- Žlajpah, Leon (15 December 2008). "Simulation in robotics". Mathematics and Computers in Simulation. 79 (4): 879–897. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2008.02.017.

- News, Technology Research. "Evolution trains robot teams TRN 051904". www.trnmag.com.

- Agarwal, P.K. Elements of Physics XI. Rastogi Publications. p. 2. ISBN 978-81-7133-911-2.

- Tandon, Prateek (2017). Quantum Robotics. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-1627059138.

- "Career: Robotics Engineer". Princeton Review. 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Saad, Ashraf; Kroutil, Ryan (2012). Hands-on Learning of Programming Concepts Using Robotics for Middle and High School Students. Proceedings of the 50th Annual Southeast Regional Conference of the Association for Computer Machinery. ACM. pp. 361–362. doi:10.1145/2184512.2184605.

- "Robotics Degree Programs at Worcester Polytechnic Institute". Worcester Polytechnic Institute. 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Student AUV Competition Europe".

- "B.E.S.T. Robotics".

- "LEGO® Building & Robotics After School Programs". Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "Decolonial AI: Decolonial Theory as Sociotechnical Foresight in Artificial Intelligence" (PDF). Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Decolonial Robotics". 9 September 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Toy, Tommy (29 June 2011). "Outlook for robotics and Automation for 2011 and beyond are excellent says expert". PBT Consulting. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Frey, Carl Benedikt; Osborne, Michael A. (1 January 2017). "The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 114: 254–280. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.416. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019. ISSN 0040-1625.

- E McGaughey, 'Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy' (2018) SSRN, part 2(3). DH Autor, ‘Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation’ (2015) 29(3) Journal of Economic Perspectives 3.

- Hawking, Stephen (1 January 2016). "This is the most dangerous time for our planet". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "Focal Points Seminar on review articles in the future of work – Safety and health at work – EU-OSHA". osha.europa.eu. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Robotics: Redefining crime prevention, public safety and security". SourceSecurity.com.

- "Draft Standard for Intelligent Assist Devices — Personnel Safety Requirements" (PDF).

- "ISO/TS 15066:2016 – Robots and robotic devices – Collaborative robots".

Further reading

- R. Andrew Russell (1990). Robot Tactile Sensing. New York: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-781592-0.

- E McGaughey, 'Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy' (2018) SSRN, part 2(3)

- DH Autor, ‘Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation’ (2015) 29(3) Journal of Economic Perspectives 3