Robot locomotion

Robot locomotion is the collective name for the various methods that robots use to transport themselves from place to place.

Wheeled robots are typically quite energy efficient and simple to control. However, other forms of locomotion may be more appropriate for a number of reasons, for example traversing rough terrain, as well as moving and interacting in human environments. Furthermore, studying bipedal and insect-like robots may beneficially impact on biomechanics.

A major goal in this field is in developing capabilities for robots to autonomously decide how, when, and where to move. However, coordinating numerous robot joints for even simple matters, like negotiating stairs, is difficult. Autonomous robot locomotion is a major technological obstacle for many areas of robotics, such as humanoids (like Honda's Asimo).

Types of locomotion

Walking

- See Passive dynamics

- See Zero Moment Point

- See Leg mechanism

- See Hexapod (robotics)

Walking robots simulate human or animal gait, as a replacement for wheeled motion. Legged motion makes it possible to negotiate uneven surfaces, steps, and other areas that would be difficult for a wheeled robot to reach, as well as causes less damage to environmental terrain as wheeled robots, which would erode it.[1]

Hexapod robots are based on insect locomotion, most popularly the cockroach[2] and stick insect, whose neurological and sensory output is less complex than other animals. Multiple legs allow several different gaits, even if a leg is damaged, making their movements more useful in robots transporting objects.

Examples of advanced running robots include ASIMO, BigDog, HUBO 2, RunBot, and Toyota Partner Robot.

Rolling

In terms of energy efficiency on flat surfaces, wheeled robots are the most efficient. This is because an ideal rolling (but not slipping) wheel loses no energy. A wheel rolling at a given velocity needs no input to maintain its motion. This is in contrast to legged robots which suffer an impact with the ground at heelstrike and lose energy as a result.

For simplicity most mobile robots have four wheels or a number of continuous tracks. Some researchers have tried to create more complex wheeled robots with only one or two wheels. These can have certain advantages such as greater efficiency and reduced parts, as well as allowing a robot to navigate in confined places that a four-wheeled robot would not be able to.

Examples: Boe-Bot, Cosmobot, Elmer, Elsie, Enon, HERO, IRobot Create, iRobot's Roomba, Johns Hopkins Beast, Land Walker, Modulus robot, Musa, Omnibot, PaPeRo, Phobot, Pocketdelta robot, Push the Talking Trash Can, RB5X, Rovio, Seropi, Shakey the robot, Sony Rolly, Spykee, TiLR, Topo, TR Araña, and Wakamaru.

Hopping

Several robots, built in the 1980s by Marc Raibert at the MIT Leg Laboratory, successfully demonstrated very dynamic walking. Initially, a robot with only one leg, and a very small foot, could stay upright simply by hopping. The movement is the same as that of a person on a pogo stick. As the robot falls to one side, it would jump slightly in that direction, in order to catch itself.[3] Soon, the algorithm was generalised to two and four legs. A bipedal robot was demonstrated running and even performing somersaults.[4] A quadruped was also demonstrated which could trot, run, pace, and bound.[5]

Examples:

Metachronal motion

Coordinated, sequential mechanical action having the appearance of a traveling wave is called a metachronal rhythm or wave, and is employed in nature by ciliates for transport, and by worms and arthropods for locomotion.

Slithering

Several snake robots have been successfully developed. Mimicking the way real snakes move, these robots can navigate very confined spaces, meaning they may one day be used to search for people trapped in collapsed buildings.[8] The Japanese ACM-R5 snake robot[9] can even navigate both on land and in water.[10]

Examples: Snake-arm robot, Roboboa, and Snakebot.

Swimming

Brachiating

Brachiation allows robots to travel by swinging, using energy only to grab and release surfaces.[11] This motion is similar to an ape swinging from tree to tree. The two types of brachiation can be compared to bipedal walking motions (continuous contact) or running (richochetal). Continuous contact is when a hand/grasping mechanism is always attached to the surface being crossed; richochetal employs a phase of aerial "flight" from one surface/limb to the next.

Hybrid

Robots can also be designed to perform locomotion in multiple modes. For example, the Bipedal Snake Robo [12] can both slither like a snake and walk like a biped robot.

Biologically inspired Locomotion

The desire to create robots with dynamic locomotive abilities has driven scientists to look to nature for solutions. Several robots capable of basic locomotion in a single mode have been invented but are found to lack several capabilities hence limiting its functions and applications. Highly intelligent robots are needed in several areas such as search and rescue missions, battlefields, and landscape investigation. Thus robots of this nature need to be small, light, quick, and possess the ability to move in multiple locomotive modes. As it turns out, multiple animals have provided inspiration for the design of several robots. Some of such animals are:

Pteryomini (Flying Squirrel)

The Pteryomini exhibits great mobility while on land by making use of its quadruped walking with high DoF legs. In air, the Pteryomini glides through by utilizing lift forces from the membrane between its legs. It possesses a highly flexible membrane that allows for unrestrained movement of its legs.[13] It uses its highly elastic membrane to glide while in air and it demonstrates lithe movement on the ground. In addition, the Pteryomini is able to exhibit multi-modal locomotion due to the membrane that connects the fore and hind legs which also enhances its gliding ability.[13] It has been proven that a flexible membrane possesses a higher lift coefficient than rigid plates and delays the angle of attack at which stall occurs.[13] The flying squirrel also possesses thick bundles on the edges of its membrane, wingtips and tail which helps to minimize fluctuations and unnecessary energy loss.[13]

The Pteromyini is able to boost its gliding ability due to the numerous physical attributes it possesses

The flexible muscle structure serves multiple purposes. For one, the Plagiopatagium, which serves as the primary generator of lift for the flying squirrel, is able to effectively function due to its thin and flexible muscles.[14][15] The Plagiopatagium is able to control tension on the membrane due to contraction and expansion. Tension control can ultimately help in energy savings due to minimized fluttering of the membrane. Once it lands, the Pteromyini contracts its membrane to ensure that the membrane does not sag when it is walking[15]

The propatagium and uropatagium serve to provide extra lift for the Pteromyini.[15] While the propatagium is situated between the head and forelimbs of the flying squirrel, the uropatagium is located at the tail and hind limbs and these serve to provide the flying squirrel with increased agility and drag for landing.[15]

Additionally, the flying squirrel possesses thick rope-like muscle structures on the edges of its membrane to maintain the shape of the membrane[15] s. These muscular structures called platysma, tibiocarpalis, and semitendinosus, are located on the propatagium and, plagiopatagium and uropatagium respectively.[15] These thick muscle structures serve to guard against unnecessary fluttering due to strong wind pressures during gliding hence minimizing energy loss.[15]

The wingtips are situated at the forelimb wrists and serve to form an airfoil which minimizes the effect of induced drag due to the formation of wingtip vortices.[14] The wingtips dampen the effects of the vortices and obstructs the induced drag from affecting the whole wing. The Pteryomini is able to unfold and fold its wingtips while gliding by using its thumbs. This serves to prevent undesired sagging of the wingtips.[14]

The tail of the flying squirrel allows for improved gliding abilities as it plays a critical role. As opposed to other vertebrates, the Pteromyini possesses a tail that is flattened to gain more aerodynamic surface as it glides.[16][17] This also allows the flying squirrel to maintain pitch angle stability of its tail. This is particularly useful during landing as the Pteromyini is able to widen its pitch angle and induce more drag so as to decelerate and land safely[15]

Furthermore, the legs and tail of the Pteromyini serve to control its gliding direction. Due to the flexibility of the membranes around the legs, the chord angle and dihedral angle between the membrane and coronal plane of the body is controlled.[13] This allows the animal to create rolling, pitching, and yawing moment which in turn control the speed and direction of the gliding.[18][19] During landing, the animal is able to rapidly reduce its speed by increasing drag and changing its pitch angle using its membranes and further increasing air resistance by loosening the tension between the membranes of its legs[18][19]

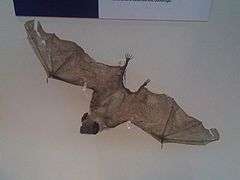

Desmodus Rotundus (Vampire Bat)

The common vampire bats are known to possess powerful modes of terrestrial locomotion, such as jumping, and aerial locomotion such as gliding. Several studies have demonstrated that the morphology of the bat enables it to easily and effectively alternate between both locomotive modes.[20] The anatomy that aids in this is essentially built around the largest muscle in the body of the bat pectorialis profundus (posterior division).[20] Between the two modes of locomotion, there are three bones that are shared. These three main bones are integral parts of the arm structure namely: humerus, ulna, and radius. Since there already exists a sharing of components for both modes, no additional muscles are needed when transitioning from jumping to gliding.[20]

A detailed study of the morphology of the shoulder of the bat shows that the bones of the arm are slightly more sturdy and the ulna and the radius have been fused so as to accommodate heavy reaction forces from the ground[20]

Schistocerca gregaria (Desert Dwelling locust)

The desert dwelling locust is known for its ability to jump and fly over long distances as well as crawl on land.[21] A detailed study of the anatomy of this organism would provide some detail about the mechanisms for locomotion. The hind legs of the locust are developed for jumping. They possess a semi-lunar process which consists of the large extensor tibiae muscle, small flexor tibiae muscle, and banana shaped thickened cuticle.[22][23] When the tibiae muscle flexes, the mechanical advantage of the muscles and the vertical thrust component of the leg extension are increased.[24] These desert dwelling locusts utilize a catapult mechanism wherein the energy is first stored in the hind legs and then released to extend the legs.[25]

In order for a perfect jump to occur, the locust must push its legs on the ground with a strong enough force so as to initiate a fast take off The force must be adequate enough in order to attain a quick take off and decent jump height. The force must also be generated quickly. In order to effectively transition from the jumping mode to the flying mode, the insect must adjust the time during the wing opening to maximize the distance and height of jump. When it is at the zenith of its jump, the flight mode becomes actuated.[22]

Multi-Modal Robot locomotion based on Bio-inspiration

Modeling of a multi-modal walking and gliding robot after the Pteryomini (Flying squirrel)

Following the discovery of the requisite model to mimic, researchers sought to design a legged robot that was capable of achieving effective motion in aerial and terrestrial environments by the use of a flexible membrane. Thus, to achieve this goal, the following design considerations had to be taken into account:

1. The shape and area of the membrane had to be consciously selected so that the intended aerodynamic capabilities of this membrane could be achieved. Additionally, the design of the membrane would affect the design of the legs since the membrane is attached to the legs.[13]

2. The membrane had to be flexible enough to allow for unrestricted movement of the legs during gliding and walking. However, the amount of flexibility had to be controlled due to the fact that excessive flexibility could lead to a significant loss of energy caused by the oscillations at regions of the membrane where strong pressure occur.[13]

3. The leg of the robot had to be designed to allow for appropriate torques for walking as well as gliding[13]

In order to incorporate these factors, close attention had to be paid to the characteristics of the Pteryomini. The aerodynamic features of the robot were modeled using the dynamic modeling and simulation. By imitating the thick muscle bundles of the membrane of the Pteryomini, the designers were able to minimize the fluctuations and oscillations on the membrane edges of the robot thus reducing needless energy loss.[13] Furthermore, the amount of drag on the wing of the robot was reduced by the use of retractable wingtips thereby allowing for improved gliding abilities.[14] Moreover, the leg of the robot was designed to incorporate sufficient torque after mimicking the anatomy of the Pteryomini’s leg using virtual work analysis.[13]

Following the design of the leg and membrane of the robot, its average gliding ratio (GR) was determined to be 1.88. The robot functioned effectively, walking in several gait patterns and crawling with its high DoF legs.[13] The robot was also able to land safely. These performances demonstrated the gliding and walking capabilities of the robot and its multi-modal locomotion

Modeling of a multi-modal jumping and gliding robot after the Desmodus Rotundus (Vampire Bat)

The design of the robot called Multi-Mo Bat involved the establishment of four primary phases of operation: energy storage phase, jumping phase, coasting phase, and gliding phase.[20] The energy storing phase essentially involves the reservation of energy for the jumping energy. This energy is stored in the main power springs. This process additionally creates a torque around the joint of the shoulders which in turn configures the legs for jumping. Once the stored energy is released, the jump phase can be initiated. When the jump phase is initiated and the robot takes off from the ground, it transitions to the coast phase which occurs until the acme is reached and it begins to descend. As the robot descends, drag helps to reduce the speed at which it descends as the wing is reconfigured due to increased drag on the bottom of the airfoils.[20] At this stage, the robot glides down.

The anatomy of the arm of the vampire bat plays a key role in the design of the leg of the robot. In order to minimize the number of Degrees of Freedom (DoFs), the two components of the arm are mirrored over the xz plane.[20] This then creates the four-bar design of the leg structure of the robot which results in only 2 independent DoFs.[20]

Modeling of a multi-modal jumping and flying robot after the Schistocerca gregaria (Desert Dwelling Locust)

The robot designed was powered by a single DC motor which integrated the performances of jumping and flapping.[23] It was designed as an incorporation of the inverted slider-crank mechanism for the construction of the legs, a dog-clutch system to serve as the mechanism for winching, and a rack-pinion mechanism used for the flapping-wing system.[20] This design incorporated a very efficient energy storage and release mechanism and an integrated wing flapping mechanism.[20]

A robot with features similar to the locust was developed. The primary feature of the robot’s design was a gear system powered by a single motor which allowed the robot to perform its jumping and flapping motions. Just like the motion of the locust, the motion of the robot is initiated by the flexing of the legs to the position of maximum energy storage after which the energy is released immediately to generate the force necessary to attain flight.[20]

The robot was tested for performance and the results demonstrated that the robot was able to jump to an approximate height of 0.9m while weighing 23g and flapping its wings at a frequency of about 19 Hz.[20] The robot tested without its flapping wings performed less impressively showing about 30% decrease in jumping performance as compared to the robot with the wings.[20] These results are quite impressive as it is expected that the reverse be the case since the weight of the wings should have impacted the jumping

Approaches

- Product optimization

- Motion planning

- Motion capture may be performed on humans, insects and other organisms.

- Machine learning, typically with reinforcement learning.

Notable researchers in the field

References

- Ghassaei, Amanda (20 April 2011). The Design and Optimization of a Crank-Based Leg Mechanism (PDF) (Thesis). Pomona College. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Sneiderman, Phil (13 February 2018). "By studying cockroach locomotion, scientists learn how to build better, more mobile robots". Hub. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "3D One-Leg Hopper (1983–1984)". MIT Leg Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- "3D Biped (1989–1995)". MIT Leg Laboratory.

- "Quadruped (1984–1987)". MIT Leg Laboratory.

- A. Spröwitz, A. Tuleu, M. Vespignani, M. Ajallooeian, E. Badri, A. J. Ijspeert (2013). "Towards dynamic trot gait locomotion: Design control and experiments with cheetah-cub a compliant quadruped robot". The International Journal of Robotics Research. 32 (8): 932–950. doi:10.1177/0278364913489205.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- H. Kimura, Y. Fukuoka, A. H. Cohen (2004). "Biologically inspired adaptive dynamic walking of a quadruped robot". Proceedings of the International Conference on the Simulation of Adaptive Behavior: 201–210.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Miller, Gavin. "Introduction". snakerobots.com. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ACM-R5 Archived 2011-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Swimming snake robot (commentary in Japanese)

- "Video: Brachiating 'Bot Swings Its Arm Like An Ape"

- Rohan Thakker, Ajinkya Kamat, Sachin Bharambe, Shital Chiddarwar and K. M. Bhurchandi. “ReBiS- Reconfigurable Bipedal Snake Robot.” In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2014.

- Shin, Won Dong; Park, Jaejun; Park, Hae-Won (July 2019). "Development and experiments of a bio-inspired robot with multi-mode in aerial and terrestrial locomotion". Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. 14 (5): 056009. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/ab2ab7. ISSN 1748-3190. PMID 31212268.

- Thorington, Richard W.; Darrow, Karolyn; Anderson, C. Gregory (1998-02-20). "Wing Tip Anatomy and Aerodynamics in Flying Squirrels". Journal of Mammalogy. 79 (1): 245–250. doi:10.2307/1382860. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 1382860.

- Johnson-Murray, Jane L. (1977-08-20). "Myology of the Gliding Membranes of Some Petauristine Rodents (Genera: Glaucomys, pteromys, petinomys, and Petaurista)". Journal of Mammalogy. 58 (3): 374–384. doi:10.2307/1379336. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 1379336.

- Norberg, Ulla M. (1985-09-01). "Evolution of Vertebrate Flight: An Aerodynamic Model for the Transition from Gliding to Active Flight". The American Naturalist. 126 (3): 303–327. doi:10.1086/284419. ISSN 0003-0147.

- Paskins, Keith E.; Bowyer, Adrian; Megill, William M.; Scheibe, John S. (2007-04-15). "Take-off and landing forces and the evolution of controlled gliding in northern flying squirrels Glaucomys sabrinus". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (8): 1413–1423. doi:10.1242/jeb.02747. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 17401124.

- Bishop, Kristin L. (2006-02-15). "The relationship between 3-D kinematics and gliding performance in the southern flying squirrel, Glaucomys volans". Journal of Experimental Biology. 209 (4): 689–701. doi:10.1242/jeb.02062. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 16449563.

- Bishop, Kristin L. (2007-08-01). "Aerodynamic force generation, performance and control of body orientation during gliding in sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (15): 2593–2606. doi:10.1242/jeb.002071. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 17644674.

- Woodward, Matthew A.; Sitti, Metin (2014-09-04). "MultiMo-Bat: A biologically inspired integrated jumping–gliding robot". The International Journal of Robotics Research. 33 (12): 1511–1529. doi:10.1177/0278364914541301. ISSN 0278-3649.

- Rillich, Jan; Stevenson, Paul A.; Pflueger, Hans-Joachim (2013-05-09). "Flight and Walking in Locusts–Cholinergic Co-Activation, Temporal Coupling and Its Modulation by Biogenic Amines". PLOS One. 8 (5): e62899. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862899R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062899. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3650027. PMID 23671643.

- "How Grasshoppers Jump". www.st-andrews.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- Truong, Ngoc Thien; Phan, Hoang Vu; Park, Hoon Cheol (2019-03-13). "Design and demonstration of a bio-inspired flapping-wing-assisted jumping robot". Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. 14 (3): 036010. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/aafff5. ISSN 1748-3190. PMID 30658344.

- Burrows, M. (1995-05-01). "Motor patterns during kicking movements in the locust". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 176 (3): 289–305. doi:10.1007/BF00219055. ISSN 1432-1351. PMID 7707268.

- Burrows, Malcolm; Sutton, Gregory P. (2012-10-01). "Locusts use a composite of resilin and hard cuticle as an energy store for jumping and kicking". Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (19): 3501–3512. doi:10.1242/jeb.071993. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 22693029.