Yinotheria

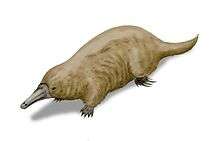

Yinotheria is a proposed basal subclass clade of crown mammals that contains a few fossils of the Mesozoic and the extant monotremes.[3] Today, there are only five surviving species, which live in Australia and New Guinea, but fossils have been found in England, China, Russia, Madagascar and Argentina. The surviving species consist of the platypus and four species of echidna.

| Yinotheria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Platypus) | |

| |

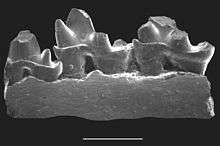

| Ambondro mahabo jawbone | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Subclass: | Yinotheria Chow and Rich, 1982[2] |

| Subgroups | |

Evolutionary history

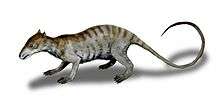

According to genetic studies, Yinotheria diverged from other mammals around 220 to 210 million years ago, at some point in the Triassic or Early Jurassic.[1][4] The oldest-known fossils are a bit younger, dating around 168 to 163 million years in the Middle Jurassic. These fossils are the genera Pseudotribos of China,[3] Shuotherium of both China and England, Itatodon of Siberia and Paritatodon of Kyrgyzstan and England.[5] These, which belong to the family Shuotheriidae, are the only known northern hemisphere group of yinotherians.

The infraclass Australosphenida appeared around the same time as Shuotheriidae. The family Henosferidae, comprising the genera Henosferus, Ambondro, and Asfaltomylos, has been found in the southern hemisphere at locations in Argentina and Madagascar. This suggests that this family could have been more widespread and diverse in Gondwana during that time; however, due to their fragile state, some fossils might have been destroyed by geological events.

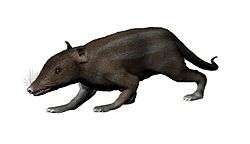

The family Ausktribosphenidae and the first monotremes appeared in the Early Cretaceous, in the region that is now known as Australasia. Despite being found in the same region of the world and in the same time period, recent work has found that the older Henosferidae is the sister taxon to Monotremata, with Ausktribosphenidae being the next sister taxa in Australosphenida.[6] Ausktribosphenidae includes the genera Bishops and Ausktribosphenos.

Some 110-million-year-old monotreme fossil jaw fragments were found at Lightning Ridge, New South Wales. These fragments, from the species Steropodon galmani, are the oldest known monotreme fossils. Fossils from the genera Kollikodon, Teinolophos, and Obdurodon have also been discovered. In 1991, a fossil tooth of a 61-million-year-old platypus was found in southern Argentina (since named Monotrematum, though it is now considered to be an Obdurodon species). (See fossil monotremes below.) Molecular clock and fossil dating give a wide range of dates for the split between echidnas and platypuses, with one survey putting the split at 19 to 48 million years ago,[7] but another putting it at 17 to 89 million years ago.[8] All these dates are more recent than the oldest known platypus fossils, suggesting that both the short-beaked and long-beaked echidna species are derived from a platypus-like ancestor.

Systematics

History of classification

Prototheria

Originally, monotremes were classified as a subclass of mammals known as Prototheria. The names Prototheria, Metatheria and Eutheria (meaning "first beasts", "changed beasts", and "true beasts", respectively) refer to the three mammalian groupings that have living representatives. Each of the three may be defined as a total clade containing a living crown-group (respectively, the Monotremata, Marsupialia and Placentalia) plus any fossil species that are more closely related to that crown-group than to any other living animals.

The threefold division of living mammals into monotremes, marsupials and placentals was already well established when Thomas Huxley proposed the names Metatheria and Eutheria to incorporate the two latter groups in 1880. Initially treated as subclasses, Metatheria and Eutheria are by convention now grouped as infraclasses of the subclass Theria, and in more recent proposals have been demoted further (to cohorts or even magnorders), as cladistic reappraisals of the relationships between living and fossil mammals have suggested that the Theria itself should be reduced in rank.[9]

Prototheria, on the other hand, was generally recognised as a subclass until quite recently, on the basis of a hypothesis that defined the group by two supposed synapomorphies: (1) formation of the side wall of the braincase from a bone called the anterior lamina, contrasting with the alisphenoid in therians; and (2) a linear alignment of molar cusps, contrasting with a triangular arrangement in therians. These characters appeared to unite monotremes with a range of Mesozoic fossil orders (Morganucodonta, Triconodonta, Docodonta and Multituberculata) in a broader clade for which the name Prototheria was retained, and of which monotremes were thought to be only the last surviving branch (Benton 2005: 300, 306).

Australosphenida hypothesis and Yinotheria

The evidence that was held to support Prototheria is now universally discounted. In the first place, the examination of embryos has revealed that the development of the braincase wall is essentially identical in therians and in 'prototherians': the anterior lamina simply fuses with the alisphenoid in therians, and therefore the 'prototherian' condition of the braincase wall is primitive for all mammals, while the therian condition can be derived from it. Additionally, the linear alignment of molar cusps is also primitive for all mammals. Therefore, neither of these states can supply a uniquely shared derived character that would support a 'prototherian' grouping of orders in contradistinction to Theria (Kemp 1983).

In a further reappraisal, the molars of embryonic and fossil monotremes (living monotreme adults are toothless) appear to demonstrate an ancestral pattern of cusps that is similar to the triangular arrangement observed in therians. Some peculiarities of this dentition support an alternative grouping of monotremes with certain recently discovered fossil forms into a proposed new clade known as the Australosphenida, and also suggest that the triangular array of cusps may have evolved independently in australosphenidans and therians (Luo et al. 2001, 2002). Australosphenida is characterized by the shared presence of a cingulum on the outer front corner of the lower molars, a short and broad talonid, a relatively low trigonid, and a triangulated last lower premolar.[10]

The Australosphenida hypothesis remains controversial; for example, lingual cingula seem to be a presence in various non-australosphenidan mammals[11] and some work has shown the possibility of Eutheria being the sister group to Australosphenida, without monotremes.[12] As a result, some taxonomists (e.g. McKenna & Bell 1997) prefer to maintain the name Prototheria as a fitting contrast to the other group of living mammals, the Theria. In theory, the Prototheria is taxonomically redundant, since Monotremata is currently the only order that can still be confidently included, but its retention might be justified if new fossil evidence, or a re-examination of known fossils, enables extinct relatives of the monotremes to be identified and placed within a wider grouping.

When systematic work was performed, it was also found that Australosphenida is the sister taxon to Shuotheriidae, an obscure group of Mesozoic mammals that were found in what is now China. Kielan-Jaworowska, Cifelli & Luo 2002 had this to say regarding the Shuotheriidae, particularly Shuotherium:[13]

In our view, the most compelling evidence as to the affinities of Shuotherium lies in the structure of the last premolar, which shares striking similarities to that of Australosphenida

Lower molar structure of Shuotherium and Australosphenida is obviously quite different, and for this reason we do not place Shuotherium within this Gondwanan clade. Based on the limited evidence available, however, we suggest that Shuotherium is a viable sister-taxon to Australosphenida.

Taxonomy

In comparison to Metatheria and Eutheria, where there seems to be a better understanding on the relationships among taxa with substantial fossil evidence, Yinotheria has few fossils; mostly consisting of (with few exceptions) the jawbones and teeth. In addition, the group seems not to have been as diverse in their evolutionary history, in comparison to members of both Metatheria and Eutheria.[15] Future analysis and better fossil remains could affect the membership of Yinotheria as well as rearranging and revising the relationships of stem-monotremes and crowned monotremes.

- Subclass Yinotheria Chow & Rich 1982 sensu Kielan-Jaworowska, Cifelli & Luo 2004 [Prototheria Gill 1872]

- Order †Shuotherida Chow & Rich 1982 [Shuotheridia; Shuotheria]

- Family †Shuotheriidae Chow & Rich 1982

- Genus †Pseudotribos Luo, Ji & Yuan 2007

- †Pseudotribos robustus Luo, Ji & Yuan 2007

- Genus †Shuotherium Chow & Rich 1982

- †Shuotherium dongi Chow & Rich 1982

- †Shuotherium shilongi Wang et al. 1998

- Genus †Pseudotribos Luo, Ji & Yuan 2007

- Family †Shuotheriidae Chow & Rich 1982

- Infraclass Australosphenida Luo, Cifelli & Kielan-Jaworowska 2001 sensu Kielan-Jaworowska, Cifelli & Luo 2004

- Order †Ausktribosphenida Luo, Cifelli & Kielan-Jaworowska 2001

- Family †Ausktribosphenidae Rich et al. 1997

- Genus †Bishops Rich et al. 2001

- †Bishops whitmorei Rich et al. 2001

- Genus †Ausktribosphenos Rich et al. 1997

- †Ausktribosphenos nyktos Rich et al. 1997

- Genus †Bishops Rich et al. 2001

- Family †Ausktribosphenidae Rich et al. 1997

- Order †Henosferida Averianov & Lopatin 2011

- Family †Henosferidae Rougier et al. 2007

- Genus †Ambondro[16]

- †Ambondro mahabo Flynn et al. 1999

- Genus †Asfaltomylos Rauhut et al. 2002

- †Asfaltomylos patagonicus Rauhut et al. 2002

- Genus †Henosferus Rougier et al. 2007

- †Henosferus molus Rougier et al. 2007

- Genus †Ambondro[16]

- Family †Henosferidae Rougier et al. 2007

- Order Monotremata Bonaparte 1837 sensu Luo, Cifelli & Kielan-Jaworowska 2001

- Genus †Kryoryctes Pridmore et al. 2005 (either a stem-monotreme[17] or junior synonym of Steropodon[18])

- †Kryoryctes cadburyi Pridmore et al. 2005

- Suborder Tachyglossa Gill 1872

- Family Tachyglossidae Gill 1872 [ Echidnidae Burnett 1830] (echidnas, spiny anteaters)

- Genus †Megalibgwilia Griffiths, Wells & Barrie 1991 (subjective synonym or subgenus of Zaglossus)

- †Megalibgwilia robusta (Dun 1895) (subjective synonym of Zaglossus robustus)

- †Megalibgwilia ramsayi (Owen 1884) (senior synonym of Megalibgwilia owenii[15])

- Genus Zaglossus Gill 1877 [Proechidna Gervais 1877; Acanthoglossus Gervais 1877; Bruynia Dubois 1882; Bruijia Thomas 1883; Prozaglossus Kerbert 1913] (Long-beaked Echidnas)

- †Zaglossus hacketti Glauert 1914 (Hackett's Giant Echidna) (might belong to a new genus[15])

- Zaglossus bruijni (Peters & Doria 1876) (Western Long-beaked/Bruinj's/Brown False Echidna)

- Zaglossus attenboroughii Flannery & Groves 1998 (Attenborough's/Sir David’s/Cyclops Long-beaked Echidna)

- Zaglossus bartoni Thomas 1907 (Eastern/Barton’s Long-beaked/Grey False Echidna)

- Genus Tachyglossus Illiger 1811 [Acanthonotus Goldfuss 1809; Echidna Cuvier 1798; Echinopus Fischer de Waldheim 1814; Syphomia Rafinesque 1815]

- Tachyglossus aculeatus (Shaw 1792) Illiger 1811 (short-beaked Echidna)

- Genus †Megalibgwilia Griffiths, Wells & Barrie 1991 (subjective synonym or subgenus of Zaglossus)

- Family Tachyglossidae Gill 1872 [ Echidnidae Burnett 1830] (echidnas, spiny anteaters)

- Suborder Platypoda Gill 1872

- Family †Kollikodontidae Flannery et al. 1995

- Genus †Kollikodon Flannery et al. 1995 (might be a mammaliform of uncertain placement[15])

- †Kollikodon ritchiei Flannery et al. 1995

- Genus †Kollikodon Flannery et al. 1995 (might be a mammaliform of uncertain placement[15])

- Family †Steropodontidae Archer et al. 1985

- Genus †Teinolophos Rich et al. 1999 (might be a basal monotreme or a stem-monotreme[15])

- †Teinolophos trusleri Rich et al. 1999

- Genus †Steropodon Archer et al. 1985

- †Steropodon galmani Archer et al. 1985

- Genus †Teinolophos Rich et al. 1999 (might be a basal monotreme or a stem-monotreme[15])

- Family Ornithorhynchidae Gray 1825

- Genus †Monotrematum Pascual et al. 1992 (here considered to be a basal ornithorhynchid;[15] others subjective synonym of Obdurodon)

- †Monotrematum sudamericanum Pascual et al. 1992

- Genus †Obdurodon Woodburne & Tedford 1975

- †Obdurodon insignis Woodburne & Tedford 1975

- †Obdurodon tharalkooschild Pian, Archer & Hand 2013

- †Obdurodon dicksoni Archer et al. 1992 (Riversleigh platypus)

- Genus Ornithorhynchus Blumenbach 1800 [Dermipus Wiedermann 1800; Platypus Shaw 1799 non Herbst 1793]

- Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw 1799) Blumenbach 1800 (platypus)

- Genus †Monotrematum Pascual et al. 1992 (here considered to be a basal ornithorhynchid;[15] others subjective synonym of Obdurodon)

- Family †Kollikodontidae Flannery et al. 1995

- Genus †Kryoryctes Pridmore et al. 2005 (either a stem-monotreme[17] or junior synonym of Steropodon[18])

- Order †Ausktribosphenida Luo, Cifelli & Kielan-Jaworowska 2001

- Order †Shuotherida Chow & Rich 1982 [Shuotheridia; Shuotheria]

Phylogeny

Below is a simplified tree on Averianov et. al, 2014[6] after Woodburn, 2003[16] and Ashwell, 2013[15]

| Yinotheria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Hugall, A.F.; et al. (2007). "Calibration choice, rate smoothing, and the pattern of tetrapod diversification according to the long nuclear gene RAG-1". Syst. Biol. 56 (4): 543–63. doi:10.1080/10635150701477825. PMID 17654361.

- Chow, M.; Rich, T. H. (1982). "Shuotherium dongi, n. gen. and sp., a therian with pseudo-tribosphenic molars from the Jurassic of Sichuan, China". Australian Mammalogy. 5: 127–42.

- Luo, Zhe-Xi; Ji, Qiang; Yuan, Chong-Xi (2007). "Convergent dental adaptations in pseudo-tribosphenic and tribosphenic mammals". Nature. 450 (7166): 93–97. Bibcode:2007Natur.450...93L. doi:10.1038/nature06221. PMID 17972884. Retrieved September 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - http://timetree.org/pdf/Madsen2009Chap68.pdf

- Wang, Y.-Q. and Li, C.-K. 2016. Reconsideration of the systematic position of the Middle Jurassic mammaliaforms Itatodon and Paritatodon. Palaeontologia Polonica 67, 249–256.

- Averianov et. al, 2014

- Phillips, MJ; Bennett, TH; Lee, MS. (2009). "Molecules, morphology, and ecology indicate a recent, amphibious ancestry for echidnas". PNAS. 106 (40): 17089–17094. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10617089P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904649106. PMC 2761324. PMID 19805098.

- http://timetree.org/pdf/Springer2009Chap69.pdf

- Marsupialia and Eutheria/Placentalia appear as cohorts in McKenna & Bell 1997 and in Benton 2005, with Theria ranked as a supercohort or an infralegion, respectively.

- Luo et al., 2001, pp. 53, 56

- Sigogneau-Russell et al., 2001, p. 146

- Woodburne, 2003, fig. 5; Woodburne et al., 2003, fig. 3

- Dykes: Shuoterium

- Kielan-Jaworowska, Cifelli & Luo 2004, pp. 214–215, 529

- Ashwell, 2013

- Woodburne, 2003

- Pridmore, Peter A.; et al. (December 2005), "A Tachyglossid-Like Humerus from the Early Cretaceous of South-Eastern Australia", Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 12 (3–4): 359–378, doi:10.1007/s10914-005-6959-9

- Phillips, Matthew J.; et al. (2010), "Reply to Camens: How recently did modern monotremes diversify?", Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 107:E13 (4): E13, Bibcode:2010PNAS..107E..13P, doi:10.1073/pnas.0913152107, PMC 2824408

- Benton, Michael J. 2005. Vertebrate Palaeontology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-632-05637-1

- Kemp, T.S. (1983). "The relationships of mammals". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 77: 353–84. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1983.tb00859.x.

- Luo, Z.-X.; Cifelli, R.L.; Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. (2001). "Dual origin of tribosphenic mammals". Nature. 409: 53–7. Bibcode:2001Natur.409...53L. doi:10.1038/35051023. PMID 11343108.

- Luo, Z.-X.; Cifelli, R.L.; Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. (2002). "In quest for a phylogeny of Mesozoic mammals". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 47: 1–78.

- McKenna, Malcolm C., and Susan K. Bell. 1997. Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11013-8

- Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, Richard L. Cifelli, and Zhe-Xi Luo, Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 214-215.

External links