Turboprop

A turboprop engine is a turbine engine that drives an aircraft propeller.[1]

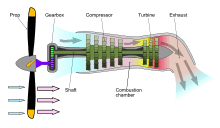

In its simplest form a turboprop consists of an intake, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle.[2] Air is drawn into the intake and compressed by the compressor. Fuel is then added to the compressed air in the combustor, where the fuel-air mixture then combusts. The hot combustion gases expand through the turbine. Some of the power generated by the turbine is used to drive the compressor. Thrust is obtained by the combusting gases, pushing toward a (vectored) surface in front of the expanding gas.

The rest is transmitted through the reduction gearing to the propeller. Further expansion of the gases occurs in the propelling nozzle, where the gases exhaust to atmospheric pressure. The propelling nozzle provides a relatively small proportion of the thrust generated by a turboprop.[3]

In contrast to a turbojet, the engine's exhaust gases do not generally contain enough energy to create significant thrust, since almost all of the engine's power is used to drive the propeller.

Technological aspects

Exhaust thrust in a turboprop is sacrificed in favour of shaft power, which is obtained by extracting additional power (up to that necessary to drive the compressor) from turbine expansion. Owing to the additional expansion in the turbine system, the residual energy in the exhaust jet is low.[4][5][6] Consequently, the exhaust jet typically produces around or less than 10% of the total thrust.[7] A higher proportion of the thrust comes from the propeller at low speeds and less at higher speeds.[8]

Turboprops can have bypass ratios up to 50-100[9][10][11] although the propulsion airflow is less clearly defined for propellers than for fans.[12][13]

The propeller is coupled to the turbine through a reduction gear that converts the high RPM/low torque output to low RPM/high torque. The propeller itself is normally a constant-speed (variable pitch) propeller type similar to that used with larger aircraft reciprocating engines.

Unlike the small diameter fans used in turbofan jet engines, the propeller has a large diameter that lets it accelerate a large volume of air. This permits a lower airstream velocity for a given amount of thrust. As it is more efficient at low speeds to accelerate a large amount of air by a small degree than a small amount of air by a large degree,[14][15] a low disc loading (thrust per disc area) increases the aircraft's energy efficiency, and this reduces the fuel use.[16][17]

Propellers lose efficiency as aircraft speed increases, so turboprops are normally not used on high-speed aircraft[4][5][6] above 0.6–0.7 Mach.[7] However, propfan engines, which are very similar to turboprop engines, can cruise at flight speeds approaching 0.75 Mach. To increase propeller efficiency across a wider range of airspeeds, turboprops are typically equipped with constant-speed (variable-pitch) propellers. The blades of a constant-speed propeller increase pitch as aircraft speed increases, allowing for a wider range of airspeeds than a fixed-pitch propeller. Another benefit of this type of propeller is that it can also be used to generate negative thrust while decelerating on the runway. Additionally, in the event of an engine failure, the propeller can be feathered, thus minimizing the drag of the non-functioning propeller.[18]

While most modern turbojet and turbofan engines use axial-flow compressors, turboprop engines usually contain at least one stage of centrifugal compressor which have the advantage of being simple and lightweight, at the expense of a streamlined shape.

While the power turbine may be integral with the gas generator section, many turboprops today feature a free power turbine on a separate coaxial shaft. This enables the propeller to rotate freely, independent of compressor speed.[19] Residual thrust on a turboshaft is avoided by further expansion in the turbine system and/or truncating and turning the exhaust 180 degrees, to produce two opposing jets. Apart from the above, there is very little difference between a turboprop and a turboshaft.[11]

History

Alan Arnold Griffith had published a paper on turbine design in 1926. Subsequent work at the Royal Aircraft Establishment investigated axial turbine designs that could be used to supply power to a shaft and thence a propeller. From 1929, Frank Whittle began work on centrifugal turbine designs that would deliver pure jet thrust.[20]

The world's first turboprop was designed by the Hungarian mechanical engineer György Jendrassik.[21] Jendrassik published a turboprop idea in 1928, and on 12 March 1929 he patented his invention. In 1938, he built a small-scale (100 Hp; 74.6 kW) experimental gas turbine.[22] The larger Jendrassik Cs-1, with a predicted output of 1,000 bhp, was produced and tested at the Ganz Works in Budapest between 1937 and 1941. It was of axial-flow design with 15 compressor and 7 turbine stages, annular combustion chamber and many other modern features. First run in 1940, combustion problems limited its output to 400 bhp. In 1941, the engine was abandoned due to war, and the factory was turned over to conventional engine production. The world's first turboprop engine that went into mass production was designed by a German engineer, Max Adolf Mueller, in 1942.[23]

The first mention of turboprop engines in the general public press was in the February 1944 issue of the British aviation publication Flight, which included a detailed cutaway drawing of what a possible future turboprop engine could look like. The drawing was very close to what the future Rolls-Royce Trent would look like.[24] The first British turboprop engine was the Rolls-Royce RB.50 Trent, a converted Derwent II fitted with reduction gear and a Rotol 7 ft 11 in (2.41 m) five-bladed propeller. Two Trents were fitted to Gloster Meteor EE227 — the sole "Trent-Meteor" — which thus became the world's first turboprop-powered aircraft, albeit a test-bed not intended for production.[25][26] It first flew on 20 September 1945. From their experience with the Trent, Rolls-Royce developed the Rolls-Royce Clyde, the first turboprop engine to be fully type certificated for military and civil use,[27] and the Dart, which became one of the most reliable turboprop engines ever built. Dart production continued for more than fifty years. The Dart-powered Vickers Viscount was the first turboprop aircraft of any kind to go into production and sold in large numbers.[28] It was also the first four-engined turboprop. Its first flight was on 16 July 1948. The world's first single engined turboprop aircraft was the Armstrong Siddeley Mamba-powered Boulton Paul Balliol, which first flew on 24 March 1948.[29]

The Soviet Union built on German World War II development by Junkers Motorenwerke, while BMW, Heinkel-Hirth and Daimler-Benz also developed and partially tested designs. While the Soviet Union had the technology to create the airframe for a jet-powered strategic bomber comparable to Boeing's B-52 Stratofortress, they instead produced the Tupolev Tu-95 Bear, powered with four Kuznetsov NK-12 turboprops, mated to eight contra-rotating propellers (two per nacelle) with supersonic tip speeds to achieve maximum cruise speeds in excess of 575 mph, faster than many of the first jet aircraft and comparable to jet cruising speeds for most missions. The Bear would serve as their most successful long-range combat and surveillance aircraft and symbol of Soviet power projection throughout the end of the 20th century. The USA would incorporate contra-rotating turboprop engines, such as the ill-fated twin-turbine Allison T40 — essentially a twinned up pair of Allison T38 turboprop engines driving contra-rotating propellers – into a series of experimental aircraft during the 1950s, with aircraft powered with the T40, like the Convair R3Y Tradewind flying boat never entering U.S. Navy service.

The first American turboprop engine was the General Electric XT31, first used in the experimental Consolidated Vultee XP-81.[30] The XP-81 first flew in December 1945, the first aircraft to use a combination of turboprop and turbojet power. The technology of the Allison's earlier T38 design evolved into the Allison T56, with quartets of the T56s being used to power the Lockheed Electra airliner, its military maritime patrol derivative the P-3 Orion, and the widely produced C-130 Hercules military transport aircraft. One of the most produced turboprop engines used in civil aviation is the Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6 engine.

The first turbine-powered, shaft-driven helicopter was the Kaman K-225, a development of Charles Kaman's K-125 synchropter, which used a Boeing T50 turboshaft engine to power it on 11 December 1951.[31]

Usage

Compared to turbofans, turboprops are most efficient at flight speeds below 725 km/h (450 mph; 390 knots) because the jet velocity of the propeller (and exhaust) is relatively low. Modern turboprop airliners operate at nearly the same speed as small regional jet airliners but burn two-thirds of the fuel per passenger.[32] However, compared to a turbojet (which can fly at high altitude for enhanced speed and fuel efficiency) a propeller aircraft has a lower ceiling.

Compared to piston engines, their greater power-to-weight ratio (which allows for shorter takeoffs) and reliability can offset their higher initial cost, maintenance and fuel consumption. As jet fuel can be easier to obtain than avgas in remote areas, turboprop-powered aircraft like the Cessna Caravan and Quest Kodiak are used as bush airplanes.

Turboprop engines are generally used on small subsonic aircraft, but the Tupolev Tu-114 can reach 470 kn (870 km/h, 541 mph). Large military aircraft, like the Tupolev Tu-95, and civil aircraft, such as the Lockheed L-188 Electra, were also turboprop powered. The Airbus A400M is powered by four Europrop TP400 engines, which are the second most powerful turboprop engines ever produced, after the 11 MW (15,000 hp) Kuznetsov NK-12.

In 2017, the most widespread turboprop airliners in service were the ATR 42/72 (950 aircraft), Bombardier Q400 (506), De Havilland Canada Dash 8-100/200/300 (374), Beechcraft 1900 (328), de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter (270), Saab 340 (225).[34] Less widespread and older airliners include the BAe Jetstream 31, Embraer EMB 120 Brasilia, Fairchild Swearingen Metroliner, Dornier 328, Saab 2000, Xian MA60, MA600 and MA700, Fokker 27 and 50.

Turboprop business aircraft include the Piper Meridian, Socata TBM, Pilatus PC-12, Piaggio P.180 Avanti, Beechcraft King Air and Super King Air. In April 2017, there were 14,311 business turboprops in the worldwide fleet.[35]

Reliability

Between 2012 and 2016, the ATSB observed 417 events with turboprop aircraft, 83 per year, over 1.4 million flight hours: 2.2 per 10,000 hours. Three were "high risk" involving engine malfunction and unplanned landing in single‑engine Cessna 208 Caravans, four "medium risk" and 96% "low risk". Two occurrences resulted in minor injuries due to engine malfunction and terrain collision in agricultural aircraft and five accidents involved aerial work: four in agriculture and one in an air ambulance.[36]

Current engines

Jane's All the World's Aircraft. 2005–2006.

See also

References

Notes

- "Turboprop", Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, Federal Aviation Administration, 2009.

- "Aviation Glossary – Turboprop". dictionary.dauntless-soft.com. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Rathore, Mahesh. Thermal Engineering. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 968.

- "Turboprop Engine" Glenn Research Center (NASA)

- "Turboprop Thrust" Glenn Research Center (NASA)

- "Variations of Jet Engines". smu.edu. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ""The turbofan engine Archived 18 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine", page 7. SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Department of aerospace engineering.

- J. Russell (2 August 1996). Performance and Stability of Aircraft. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 16. ISBN 0080538649.

- Ilan Kroo and Juan Alonso. "Aircraft Design: Synthesis and Analysis, Propulsion Systems: Basic Concepts Archived 18 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine" Stanford University School of Engineering, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Main page Archived 23 February 2001 at the Wayback Machine

- Prof. Z. S. Spakovszky. "11.5 Trends in thermal and propulsive efficiency" MIT turbines, 2002. Thermodynamics and Propulsion

- Nag, P.K. "Basic And Applied Thermodynamics Archived 19 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine" p550. Published by Tata McGraw-Hill Education. Quote: "If the cowl is removed from the fan the result is a turboprop engine. Turbofan and turboprop engines differ mainly in their bypass ratio: 5 or 6 for turbofans and as high as 100 for turboprop."

- "Propeller thrust" Glenn Research Center (NASA)

- Philip Walsh, Paul Fletcher. "Gas Turbine Performance", page 36. John Wiley & Sons, 15 April 2008. Quote: "It has better fuel consumption than a turbojet or turbofan, due to a high propulsive efficiency.., achieving thrust by a high mass flow of air from the propeller at low jet velocity. Above 0.6 Mach number the turboprop in turn becomes uncompetitive, due mainly to higher weight and frontal area."

- Paul Bevilaqua. The shaft driven Lift Fan propulsion system for the Joint Strike Fighter page 3. Presented 1 May 1997. DTIC.MIL Word document, 5.5 MB. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Bensen, Igor. "How they fly – Bensen explains all" Gyrocopters UK. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Johnson, Wayne. Helicopter theory pp3+32, Courier Dover Publications, 1980. Retrieved 25 February 2012. ISBN 0-486-68230-7

- Wieslaw Zenon Stepniewski, C. N. Keys. Rotary-wing aerodynamics p3, Courier Dover Publications, 1979. Retrieved 25 February 2012. ISBN 0-486-64647-5

- "Operating Propellers during Landing & Emergencies". experimentalaircraft.info. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "An Engine Ahead of Its Time". PT6 Nation. Pratt & Whitney Canada.

- Gunston Jet, p. 120

- Gunston World, p.111

- "Magyar feltalálók és találmányok – JENDRASSIK GYÖRGY (1898–1954)". SZTNH. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- Green, W. and Swanborough, G.; "Plane Facts", Air Enthusiast Vol. 1 No. 1 (1971), Page 53.

- "Our Contribution – How Flight Introduced and Made Familiar With Gas Turbines and Jet Propulsion" Flight, 11 May 1951, p. 569.

- James p. 251-2

- Green p.18-9

- "rolls-royce trent – armstrong siddeley – 1950–2035 – Flight Archive". Flightglobal. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Green p.82

- Green p.81

- Green p.57

- "Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum – Collections – Kaman K-225 (Long Description)". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "More turboprops coming to the market – maybe". CAPA – Centre for Aviation. 9 July 2010.

- "Beechcraft King Air 350i rolls out improved situational awareness, navigation" (Press release). Textron Aviation. 30 May 2018.

- "787 stars in annual airliner census". Flightglobal. 14 August 2017.

- "Business Aviation Market Update Report" (PDF). AMSTAT, Inc. April 2017.

- Gordon Gilbert (25 June 2018). "ATSB Study Finds Turboprop Engines Safe, Reliable".

- "The H-Series Engine | Engines | B&GA | GE Aviation". www.geaviation.com. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- , PragueBest s.r.o. "History | GE Aviation". www.geaviation.cz. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

Bibliography

- Green, W. and Cross, R.The Jet Aircraft of the World (1955). London: MacDonald

- Gunston, Bill (2006). The Development of Jet and Turbine Aero Engines, 4th Edition. Sparkford, Somerset, England, UK: Patrick Stephens, Haynes Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-4477-3.

- Gunston, Bill (2006). World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines, 5th Edition. Phoenix Mill, Gloucestershire, England, UK: Sutton Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-7509-4479-X.

- James, D.N. Gloster Aircraft since 1917 (1971). London: Putnam & Co. ISBN 0-370-00084-6

Further reading

- Van Sickle, Neil D.; et al. (1999). "Turboprop Engines". Van Sickle's modern airmanship. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-07-069633-4.

External links

- Jet Turbine Planes by LtCol Silsbee USAAF, Popular Science, December 1945, first article on turboprops printed

- Wikibooks: Jet propulsion

- "Development of the Turboprop" a 1950 Flight article on UK and US turboprop engines