Specific impulse

Specific impulse (usually abbreviated Isp) is a measure of how effectively a rocket uses propellant or a jet engine uses fuel. Specific impulse can be calculated in a variety of different ways with different units. By definition, it is the total impulse (or change in momentum) delivered per unit of propellant consumed[1] and is dimensionally equivalent to the generated thrust divided by the propellant mass flow rate or weight flow rate.[2] If mass (kilogram, pound-mass, or slug) is used as the unit of propellant, then specific impulse has units of velocity. If weight (newton or pound-force) is used instead, then specific impulse has units of time (seconds). Multiplying flow rate by the standard gravity (g0) converts specific impulse from the weight basis to the mass basis.[2]

A propulsion system with a higher specific impulse uses the mass of the propellant more efficiently. In the case of a rocket or other vehicle governed by the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, this means less propellant needed for a given delta-v.[1][3] In rockets, this means that the vehicle the engine is attached to can more efficiently gain altitude and velocity. This effectiveness is less important in jet aircraft that use ambient air for combustion, and carry payloads that are much heavier than the propellant.

Specific impulse can include the contribution to impulse provided by external air that has been used for combustion and is exhausted with the spent propellant. Jet engines use outside air, and therefore have a much higher specific impulse than rocket engines. The specific impulse in terms of propellant mass spent has units of distance per time, which is a notional velocity called the effective exhaust velocity. This is higher than the actual exhaust velocity because the mass of the combustion air is not being accounted for. Actual and effective exhaust velocity are the same in rocket engines operating in a vacuum.

Specific impulse is inversely proportional to specific fuel consumption (SFC) by the relationship Isp = 1/(go·SFC) for SFC in kg/(N·s) and Isp = 3600/SFC for SFC in lb/(lbf·hr).

General considerations

The amount of propellant can be measured either in units of mass or weight. If mass is used, specific impulse is an impulse per unit mass, which dimensional analysis shows to have units of speed, specifically the effective exhaust velocity. As the SI system is mass-based, this type of analysis is usually done in meters per second. If a force-based unit system is used, impulse is divided by propellant weight (weight is a measure of force), resulting in units of time (seconds). These two formulations differ from each other by the standard gravitational acceleration (g0) at the surface of the earth.

The rate of change of momentum of a rocket (including its propellant) per unit time is equal to the thrust. The higher the specific impulse, the less propellant is needed to produce a given thrust for a given time and the more efficient the propellant is. This should not be confused with the physics concept of energy efficiency, which can decrease as specific impulse increases, since propulsion systems that give high specific impulse require high energy to do so.[4]

Thrust and specific impulse should not be confused. Thrust is the force supplied by the engine and depends on the amount of reaction mass flowing through the engine. Specific impulse measures the impulse produced per unit of propellant and is proportional to the exhaust velocity. Thrust and specific impulse are related by the design and propellants of the engine in question, but this relationship is tenuous. For example, LH2/LOx bipropellant produces higher Isp but lower thrust than RP-1/LOx due to the exhaust gases having a lower density and higher velocity (H2O vs CO2 and H2O). In many cases, propulsion systems with very high specific impulse—some ion thrusters reach 10,000 seconds—produce low thrust.[5]

When calculating specific impulse, only propellant carried with the vehicle before use is counted. For a chemical rocket, the propellant mass therefore would include both fuel and oxidizer. In rocketry, a heavier engine with a higher specific impulse may not be as effective in gaining altitude, distance, or velocity as a lighter engine with a lower specific impulse, especially if the latter engine possesses a higher thrust-to-weight ratio. This is a significant reason for most rocket designs having multiple stages. The first stage is optimised for high thrust to boost the later stages with higher specific impulse into higher altitudes where they can perform more efficiently.

For air-breathing engines, only the mass of the fuel is counted, not the mass of air passing through the engine. Air resistance and the engine's inability to keep a high specific impulse at a fast burn rate are why all the propellant is not used as fast as possible.

If it were not for air resistance and the reduction of propellant during flight, specific impulse would be a direct measure of the engine's effectiveness in converting propellant weight or mass into forward momentum.

Units

| Specific impulse | Effective exhaust velocity |

Specific fuel consumption | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By weight | By mass | |||

| SI | = x s | = 9.80665·x N·s/kg | = 9.80665·x m/s | = 101,972/x g/(kN·s) |

| English engineering units | = x s | = x lbf·s/lb | = 32.17405·x ft/s | = 3,600/x lb/(lbf·hr) |

The most common unit for specific impulse is the second, as values are identical regardless of whether the calculations are done in SI, imperial, or customary units. Nearly all manufacturers quote their engine performance in seconds, and the unit is also useful for specifying aircraft engine performance.[6]

The use of metres per second to specify effective exhaust velocity is also reasonably common. The unit is intuitive when describing rocket engines, although the effective exhaust speed of the engines may be significantly different from the actual exhaust speed, especially in gas-generator cycle engines. For airbreathing jet engines, the effective exhaust velocity is not physically meaningful, although it can be used for comparison purposes.[7]

Meters per second are numerically equivalent to Newton-seconds per kg (N·s/kg), and SI measurements of specific impulse can be written in terms of either units interchangeably.

Specific fuel consumption is inversely proportional to specific impulse and has units of g/(kN·s) or lb/(lbf·hr). Specific fuel consumption is used extensively for describing the performance of air-breathing jet engines.[8]

Specific impulse in seconds

The time unit of seconds to measure the performance of a propellant/engine combination can be thought of as "How many seconds this propellant can accelerate its own initial mass at 1 g". The more seconds it can accelerate its own mass, the more delta-V it delivers to the whole system.

In other words, given a particular engine and a pound mass of a particular propellant, specific impulse measures for how long a time that engine can exert a continuous pound of force (thrust) until fully burning through that pound of propellant. A given mass of a more energy-dense propellant can burn for a longer duration than some less energy-dense propellant made to exert the same force while burning in an engine.[note 1] Different engine designs burning the same propellant may not be equally efficient at directing their propellant's energy into effective thrust. In the same manner, some car engines are better built than others to maximize the miles-per-gallon of the gasoline they burn.

For all vehicles, specific impulse (impulse per unit weight-on-Earth of propellant) in seconds can be defined by the following equation:[9]

where:

- is the thrust obtained from the engine (newtons or pounds force),

- is the standard gravity, which is nominally the gravity at Earth's surface (m/s2 or ft/s2),

- is the specific impulse measured (seconds),

- is the mass flow rate of the expended propellant (kg/s or slugs/s)

The English unit pound mass is more commonly used than the slug, and when using pounds per second for mass flow rate, the conversion constant g0 becomes unnecessary, because the slug is dimensionally equivalent to pounds divided by g0:

Isp in seconds is the amount of time a rocket engine can generate thrust, given a quantity of propellant whose weight is equal to the engine's thrust.

The advantage of this formulation is that it may be used for rockets, where all the reaction mass is carried on board, as well as airplanes, where most of the reaction mass is taken from the atmosphere. In addition, it gives a result that is independent of units used (provided the unit of time used is the second).

Rocketry

In rocketry, the only reaction mass is the propellant, so an equivalent way of calculating the specific impulse in seconds is used. Specific impulse is defined as the thrust integrated over time per unit weight-on-Earth of the propellant:[2]

where

- is the specific impulse measured in seconds,

- is the average exhaust speed along the axis of the engine (in ft/s or m/s),

- is the standard gravity (in ft/s2 or m/s2).

In rockets, due to atmospheric effects, the specific impulse varies with altitude, reaching a maximum in a vacuum. This is because the exhaust velocity isn't simply a function of the chamber pressure, but is a function of the difference between the interior and exterior of the combustion chamber. Values are usually given for operation at sea level ("sl") or in a vacuum ("vac").

Specific impulse as effective exhaust velocity

Because of the geocentric factor of g0 in the equation for specific impulse, many prefer an alternative definition. The specific impulse of a rocket can be defined in terms of thrust per unit mass flow of propellant. This is an equally valid (and in some ways somewhat simpler) way of defining the effectiveness of a rocket propellant. For a rocket, the specific impulse defined in this way is simply the effective exhaust velocity relative to the rocket, ve. "In actual rocket nozzles, the exhaust velocity is not really uniform over the entire exit cross section and such velocity profiles are difficult to measure accurately. A uniform axial velocity, v e, is assumed for all calculations which employ one-dimensional problem descriptions. This effective exhaust velocity represents an average or mass equivalent velocity at which propellant is being ejected from the rocket vehicle."[10] The two definitions of specific impulse are proportional to one another, and related to each other by:

where

- is the specific impulse in seconds,

- is the specific impulse measured in m/s, which is the same as the effective exhaust velocity measured in m/s (or ft/s if g is in ft/s2),

- is the standard gravity, 9.80665 m/s2 (in Imperial units 32.174 ft/s2).

This equation is also valid for air-breathing jet engines, but is rarely used in practice.

(Note that different symbols are sometimes used; for example, c is also sometimes seen for exhaust velocity. While the symbol might logically be used for specific impulse in units of N·s/kg; to avoid confusion, it is desirable to reserve this for specific impulse measured in seconds.)

It is related to the thrust, or forward force on the rocket by the equation:[11]

where is the propellant mass flow rate, which is the rate of decrease of the vehicle's mass.

A rocket must carry all its propellant with it, so the mass of the unburned propellant must be accelerated along with the rocket itself. Minimizing the mass of propellant required to achieve a given change in velocity is crucial to building effective rockets. The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation shows that for a rocket with a given empty mass and a given amount of propellant, the total change in velocity it can accomplish is proportional to the effective exhaust velocity.

A spacecraft without propulsion follows an orbit determined by its trajectory and any gravitational field. Deviations from the corresponding velocity pattern (these are called Δv) are achieved by sending exhaust mass in the direction opposite to that of the desired velocity change.

Actual exhaust speed versus effective exhaust speed

When an engine is run within the atmosphere, the exhaust velocity is reduced by atmospheric pressure, in turn reducing specific impulse. This is a reduction in the effective exhaust velocity, versus the actual exhaust velocity achieved in vacuum conditions. In the case of gas-generator cycle rocket engines, more than one exhaust gas stream is present as turbopump exhaust gas exits through a separate nozzle. Calculating the effective exhaust velocity requires averaging the two mass flows as well as accounting for any atmospheric pressure.

For air-breathing jet engines, particularly turbofans, the actual exhaust velocity and the effective exhaust velocity are different by orders of magnitude. This is because a good deal of additional momentum is obtained by using air as reaction mass. This allows a better match between the airspeed and the exhaust speed, which saves energy/propellant and enormously increases the effective exhaust velocity while reducing the actual exhaust velocity.

Energy efficiency

Rockets

For rockets and rocket-like engines such as ion thrusters a higher implies lower energy efficiency, as the power needed to run the engine is as follows:

where ve is the actual exhaust jet velocity.

from momentum considerations the thrust generated is:

Dividing the power by the thrust to obtain the specific power requirements we get:

With constant thrust, the power needed increases as the exhaust velocity, leading to a lower energy efficiency per unit thrust. However, real-world vehicles are also limited in the mass amount of propellant they can carry. At low exhaust velocity the amount of reaction mass increases, at very high exhaust velocity the energy required becomes prohibitive.

Theoretically, for a given delta-v, in space, among all fixed values for the exhaust speed the value is the most energy efficient for a specified (fixed) final mass, see energy in spacecraft propulsion.

However, a variable exhaust speed can be more energy efficient still. For example, if a rocket is accelerated from some positive initial speed using an exhaust speed equal to the speed of the rocket no energy is lost as kinetic energy of reaction mass, since it becomes stationary.[12] (Theoretically, by making this initial speed low and using another method of obtaining this small speed, the energy efficiency approaches 100%, but requires a large initial mass.) In this case the rocket keeps the same momentum, so its speed is inversely proportional to its remaining mass. During such a flight the kinetic energy of the rocket is proportional to its speed and, correspondingly, inversely proportional to its remaining mass. The power needed per unit acceleration is constant throughout the flight; the reaction mass to be expelled per unit time to produce a given acceleration is proportional to the square of the rocket's remaining mass.

Also it is advantageous to expel reaction mass at a location where the gravity potential is low, see Oberth effect.

Air breathing

Air-breathing engines such as turbojets increase the momentum generated from their propellant by using it to power the acceleration of inert air rearwards. It turns out that the amount of energy needed to generate a particular amount of thrust is inversely proportional to the amount of air propelled rearwards, thus increasing the mass of air (as with a turbofan) both improves energy efficiency as well as .

Examples

| Engine type | Scenario | Spec. fuel cons. | Specific impulse (s) |

Effective exhaust velocity (m/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (lb/lbf·h) | (g/kN·s) | ||||

| NK-33 rocket engine | Vacuum | 10.9 | 308 | 331[13] | 3250 |

| SSME rocket engine | Space shuttle vacuum | 7.95 | 225 | 453[14] | 4440 |

| Ramjet | Mach 1 | 4.5 | 130 | 800 | 7800 |

| J-58 turbojet | SR-71 at Mach 3.2 (Wet) | 1.9[15] | 54 | 1900 | 19000 |

| Eurojet EJ200 | Reheat | 1.66–1.73 | 47–49[16] | 2080–2170 | 20400–21300 |

| Rolls-Royce/Snecma Olympus 593 turbojet | Concorde Mach 2 cruise (Dry) | 1.195[17] | 33.8 | 3010 | 29500 |

| Eurojet EJ200 | Dry | 0.74–0.81 | 21–23[16] | 4400–4900 | 44000–48000 |

| CF6-80C2B1F turbofan | Boeing 747-400 cruise | 0.605[17] | 17.1 | 5950 | 58400 |

| General Electric CF6 turbofan | Sea level | 0.307[17] | 8.7 | 11700 | 115000 |

| Engine | Effective exhaust velocity (m/s) |

Specific impulse (s) |

Exhaust specific energy (MJ/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turbofan jet engine (actual V is ~300 m/s) |

29,000 | 3,000 | Approx. 0.05 |

| Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster |

2,500 | 250 | 3 |

| Liquid oxygen-liquid hydrogen |

4,400 | 450 | 9.7 |

| Ion thruster | 29,000 | 3,000 | 430 |

| VASIMR[18][19][20] | 30,000–120,000 | 3,000–12,000 | 1,400 |

| Dual-stage 4-grid electrostatic ion thruster[21] | 210,000 | 21,400 | 22,500 |

| Ideal photonic rocket[lower-alpha 1] | 299,792,458 | 30,570,000 | 89,875,517,874 |

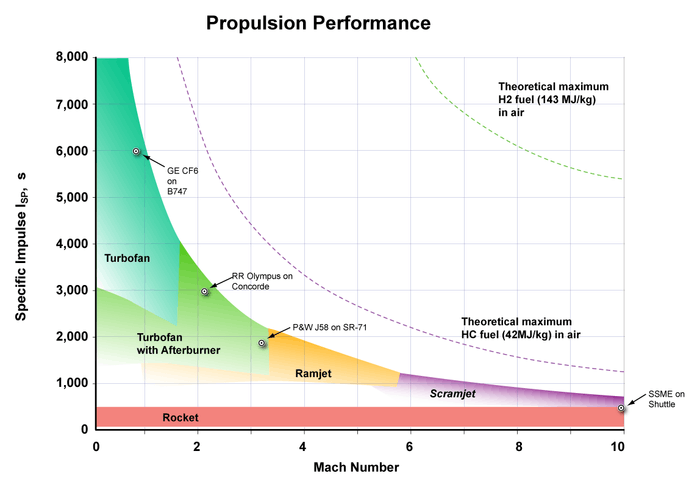

An example of a specific impulse measured in time is 453 seconds, which is equivalent to an effective exhaust velocity of 4,440 m/s, for the RS-25 engines when operating in a vacuum.[22] An air-breathing jet engine typically has a much larger specific impulse than a rocket; for example a turbofan jet engine may have a specific impulse of 6,000 seconds or more at sea level whereas a rocket would be around 200–400 seconds.[23]

An air-breathing engine is thus much more propellant efficient than a rocket engine, because the actual exhaust speed is much lower, the air provides an oxidizer, and air is used as reaction mass. Since the physical exhaust velocity is lower, the kinetic energy the exhaust carries away is lower and thus the jet engine uses far less energy to generate thrust (at subsonic speeds).[24] While the actual exhaust velocity is lower for air-breathing engines, the effective exhaust velocity is very high for jet engines. This is because the effective exhaust velocity calculation essentially assumes that the propellant is providing all the thrust, and hence is not physically meaningful for air-breathing engines; nevertheless, it is useful for comparison with other types of engines.[25]

The highest specific impulse for a chemical propellant ever test-fired in a rocket engine was 542 seconds (5.32 km/s) with a tripropellant of lithium, fluorine, and hydrogen. However, this combination is impractical. Lithium and fluorine are both extremely corrosive, lithium ignites on contact with air, fluorine ignites on contact with most fuels, and hydrogen, while not hypergolic, is an explosive hazard. Fluorine and the hydrogen fluoride (HF) in the exhaust are very toxic, which damages the environment, makes work around the launch pad difficult, and makes getting a launch license that much more difficult. The rocket exhaust is also ionized, which would interfere with radio communication with the rocket.[26] [27][28]

Nuclear thermal rocket engines differ from conventional rocket engines in that energy is supplied to the propellants by an external nuclear heat source instead of the heat of combustion.[29] The nuclear rocket typically operates by passing liquid hydrogen gas through an operating nuclear reactor. Testing in the 1960s yielded specific impulses of about 850 seconds (8,340 m/s), about twice that of the Space Shuttle engines.

A variety of other rocket propulsion methods, such as ion thrusters, give much higher specific impulse but with much lower thrust; for example the Hall effect thruster on the SMART-1 satellite has a specific impulse of 1,640 s (16,100 m/s) but a maximum thrust of only 68 millinewtons.[30] The variable specific impulse magnetoplasma rocket (VASIMR) engine currently in development will theoretically yield 20,000−300,000 m/s, and a maximum thrust of 5.7 newtons.[31]

See also

- Jet engine

- Impulse

- Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

- System-specific impulse

- Specific energy

- Standard gravity

- Thrust specific fuel consumption—fuel consumption per unit thrust

- Specific thrust—thrust per unit of air for a duct engine

- Heating value

- Energy density

- Delta-v (physics)

- Rocket propellant

- Liquid rocket propellants

Notes

- The "pound of propellant" refers to some particular mass of propellant measured in an arbitrary gravitational field (for example, Earth's); the "pound of force" refers to the force exerted by that pound-mass pressing down in the same arbitrary gravitational field; the particular acceleration of gravity is unimportant because it merely relates the two units, and thus specific impulse is not tied to gravity in any way—it is measured the same on any planet or in space.

References

- "What is specific impulse?". Qualitative Reasoning Group. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Benson, Tom (11 July 2008). "Specific impulse". NASA. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Hutchinson, Lee (14 April 2013). "New F-1B rocket engine upgrades Apollo-era design with 1.8M lbs of thrust". Ars Technica. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

The measure of a rocket's fuel effectiveness is called its specific impulse (abbreviated as 'ISP'—or more properly Isp).... 'Mass specific impulse...describes the thrust-producing effectiveness of a chemical reaction and it is most easily thought of as the amount of thrust force produced by each pound (mass) of fuel and oxidizer propellant burned in a unit of time. It is kind of like a measure of miles per gallon (mpg) for rockets.'

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Mission Overview". exploreMarsnow. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/k-12/airplane/specimp.html

- http://www.qrg.northwestern.edu/projects/vss/docs/propulsion/3-what-is-specific-impulse.html

- http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/k-12/airplane/sfc.html

- Rocket Propulsion Elements, 7th Edition by George P. Sutton, Oscar Biblarz

- George P. Sutton & Oscar Biblarz (2016). Rocket Propulsion Elements. John Wiley & Sons. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-118-75388-0.

- Thomas A. Ward (2010). Aerospace Propulsion Systems. John Wiley & Sons. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-470-82497-9.

- Note that this limits the speed of the rocket to the maximum exhaust speed.

- "NK33". Encyclopedia Astronautica.

- "SSME". Encyclopedia Astronautica.

- Nathan Meier (21 March 2005). "Military Turbojet/Turbofan Specifications".

- "EJ200 turbofan engine" (PDF). MTU Aero Engines. April 2016.

- Ilan Kroo. "Data on Large Turbofan Engines". Aircraft Design: Synthesis and Analysis. Stanford University.

- http://www.adastrarocket.com/TimSTAIF2005.pdf

- http://www.adastrarocket.com/AIAA-2010-6772-196_small.pdf

- http://spacefellowship.com/news/art24083/vasimr-vx-200-meets-full-power-efficiency-milestone.html

- http://www.esa.int/esaCP/SEMOSTG23IE_index_0.html

- http://www.astronautix.com/engines/ssme.htm

- http://web.mit.edu/16.unified/www/SPRING/propulsion/notes/node85.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/198045/effective-exhaust-velocity

- https://space.stackexchange.com/questions/19852/where-is-the-lithium-fluorine-hydrogen-tripropellant-currently/31397

- ARBIT, H. A., CLAPP, S. D., DICKERSON, R. A., NAGAI, C. K., Combustion characteristics of the fluorine-lithium/hydrogen tripropellant combination. AMERICAN INST OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS, PROPULSION JOINT SPECIALIST CONFERENCE, 4TH, CLEVELAND, OHIO, 10–14 June 1968.

- ARBIT, H. A., CLAPP, S. D., NAGAI, C. K., Lithium-fluorine-hydrogen propellant investigation Final report NASA, 1 May 1970.

- http://trajectory.grc.nasa.gov/projects/ntp/index.shtml

- http://www.mendeley.com/research/characterization-of-a-high-specific-impulse-xenon-hall-effect-thruster/

- http://www.adastrarocket.com/AdAstra%20Release%2023Nov2010final.pdf

- A hypothetical device doing perfect conversion of mass to photons emitted perfectly aligned so as to be antiparallel to the desired thrust vector. This represents the theoretical upper limit for propulsion relying strictly on onboard fuel and the rocket principle.