Posidonius

Posidonius (Greek: Ποσειδώνιος, Poseidonios, meaning "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (c. 135 BC – c. 51 BC), was a Greek[1] Stoic[2] philosopher, politician, astronomer, geographer, historian and teacher native to Apamea, Syria.[3][4]

Posidonius | |

|---|---|

Bust of Posidonius from the Naples National Archaeological Museum | |

| Born | c. 135 BC Apamea |

| Died | c. 51 BC (aged 83–84) |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Stoicism |

Main interests | Astronomy, geography, history, mathematics, meteorology, philosophy, physics |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

He was acclaimed as the greatest polymath of his age. His vast body of work exists today only in fragments.

Writers such as Strabo and Seneca provide most of the information, from history, about his life.

Early life

Posidonius, nicknamed "the Athlete", was born to a Greek[1][3] family in Apamea, a Hellenistic city on the river Orontes in northern Syria.

Posidonius completed his higher education in Athens, where he was a student of the aged Panaetius, the head of the Stoic school. But soon he came in conflict with the Stoic doctrines and was involved in heated debates with many other Stoic philosophers of the school. The incidents concerning Posidonius's conflict and final break up with the Stoics are mentioned by Galen in his book On the Doctrines of Plato and Hippocrates. Eventually Posidonius gave up Stoicism and turned to a different philosophical direction, this of Plato but mainly of Aristotle, remaining a faithful follower of Aristotelian doctrines until his death.

He settled around 95 BC in Rhodes, a maritime state which had a reputation for scientific research, and became a citizen.

Career

In Rhodes, Posidonius actively took part in political life, and his high standing is apparent from the offices he held. He attained the highest public office as one of the Prytaneis (presidents, having a six months tenure) of Rhodes. He served as an ambassador to Rome in 87–86 BC, during the Marian and Sullan era.

Along with other Greek intellectuals, Posidonius favored Rome as the stabilizing power in a turbulent world. His connections to the Roman ruling class were for him not only politically important and sensible but were also important to his scientific research. His entry into government provided Posidonius with powerful connections to facilitate his travels to far away places, even beyond Roman control.

After he had established himself in Rhodes, Posidonius made one or more journeys traveling throughout the Roman world and even beyond its boundaries to conduct scientific research. He traveled in Greece, Hispania, Italy, Sicily, Dalmatia, Gaul, Liguria, North Africa, and on the eastern shores of the Adriatic.

In Hispania, on the Atlantic coast at Gades (the modern Cadiz), Posidonius could observe tides much higher than in his native Mediterranean. He wrote that daily tides are related to the Moon's orbit, while tidal heights vary with the cycles of the Moon, and he hypothesized about yearly tidal cycles synchronized with the equinoxes and solstices.

In Gaul, he studied the Celts. He left vivid descriptions of things he saw with his own eyes while among them: men who were paid to allow their throats to be slit for public amusement and the nailing of skulls as trophies to the doorways.[5] But he noted that the Celts honored the Druids, whom Posidonius saw as philosophers, and concluded that, even among the barbaric, "pride and passion give way to wisdom, and Ares stands in awe of the Muses." He wrote a geographic treatise on the lands of the Celts which has since been lost, but which is referred to extensively (both directly and otherwise) in the works of Diodorus of Sicily, Strabo, Caesar and Tacitus' Germania.

School

Posidonius's extensive writings and lectures gave him authority as a scholar and made him famous everywhere in the Graeco-Roman world, and a school grew around him in Rhodes. His grandson Jason, who was the son of his daughter and Menekrates of Nysa, followed in his footsteps and continued Posidonius's school in Rhodes. Although little is known of the organization of his school, it is clear that Posidonius had a steady stream of Greek and Roman students.

Partial scope of writings

Posidonius was celebrated as a polymath throughout the Graeco-Roman world because he came near to mastering all the knowledge of his time, similar to Aristotle and Eratosthenes. He attempted to create a unified system for understanding the human intellect and the universe which would provide an explanation of and a guide for human behavior.

Posidonius wrote on physics (including meteorology and physical geography), astronomy, astrology and divination, seismology, geology and mineralogy, hydrology, botany, ethics, logic, mathematics, history, natural history, anthropology, and tactics. His studies were major investigations into their subjects, although not without errors.

Wilhelm Capelle (Neue Jahrbücher, 1905), traced most of the doctrines of De Mundo, to Poseidonius, a popular philosophic treatise based on two works of Poseidonius.[6]

None of his works survive intact. All that have been found are fragments, although the titles and subjects of many of his books are known.[7]

Philosophy

For Posidonius, philosophy was the dominant master art and all the individual sciences were subordinate to philosophy, which alone could explain the cosmos. All his works, from scientific to historical, were inseparably philosophical.

He accepted the Stoic categorization of philosophy into physics (natural philosophy, including metaphysics and theology), logic (including dialectic), and ethics.[8] These three categories for him were, in Stoic fashion, inseparable and interdependent parts of an organic, natural whole. He compared them to a living being, with physics the meat and blood, logic the bones and tendons holding the organism together, and finally ethics – the most important part – corresponding to the soul.[8][9] His philosophical grand vision was that the universe itself was similarly interconnected, as if an organism, through cosmic "sympathy", in all respects from the development of the physical world to the history of humanity.

Although a firm Stoic, Posidonius was, like Panaetius and other Stoics of the middle period, eclectic. He followed not only the older Stoics, but also Plato and Aristotle. Although it is not certain, Posidonius may have written a commentary on Plato's Timaeus.

He was the first Stoic to depart from the orthodox doctrine that passions were faulty judgments and posit that Plato's view of the soul had been correct, namely that passions were inherent in human nature. In addition to the rational faculties, Posidonius taught that the human soul had faculties that were spirited (anger, desires for power, possessions, etc.) and desiderative (desires for sex and food). Ethics was the problem of how to deal with these passions and restore reason as the dominant faculty.

Physics

In physics, Posidonius advocated a theory of cosmic "sympathy" (συμπάθεια, sumpatheia), the organic interrelation of all appearances in the world, from the sky to the earth, as part of a rational design uniting humanity and all things in the universe, even those that were temporally and spatially separate. Although his teacher Panaetius had doubted divination, Posidonius used Platonic philosophy to support his belief in divination – whether through astrology or prophetic dreams – as a kind of scientific prediction.[10]

Astronomy

Some fragments of his writings on astronomy survive through the treatise by Cleomedes, On the Circular Motions of the Celestial Bodies, the first chapter of the second book appearing to have been mostly copied from Posidonius.

Posidonius advanced the theory that the Sun emanated a vital force which permeated the world.

He attempted to measure the distance and size of the Sun. In about 90 BC, Posidonius estimated the distance from the Earth to the Sun (see astronomical unit) to be 9,893 times the Earth's radius. This was still too small by half. In measuring the size of the Sun, however, he reached a figure larger and more accurate than those proposed by other Greek astronomers and Aristarchus of Samos.[11]

Posidonius also calculated the size and distance of the Moon.

Posidonius constructed an orrery, possibly similar to the Antikythera mechanism. Posidonius's orrery, according to Cicero, exhibited the diurnal motions of the Sun, Moon, and the five known planets.[12]

Geography, ethnology, and geology

Posidonius's fame beyond specialized philosophical circles had begun, at the latest, in the eighties with the publication of the work "about the ocean and the adjacent areas". This work was not only an overall representation of geographical questions according to current scientific knowledge, but it served to popularize his theories about the internal connections of the world, to show how all the forces had an effect on each other and how the interconnectedness applied also to human life, to the political just as to the personal spheres.

In this work, Posidonius detailed his theory of the effect on a people's character by the climate, which included his representation of the "geography of the races". This theory was not solely scientific, but also had political implications—his Roman readers were informed that the climatic central position of Italy was an essential condition of the Roman destiny to dominate the world. As a Stoic, he did not, however, make a fundamental distinction between the civilized Romans as masters of the world and the less civilized peoples.

Like Pytheas, Posidonius believed the tide is caused by the Moon. Posidonius was, however, wrong about the cause. Thinking that the Moon was a mixture of air and fire, he attributed the cause of the tides to the heat of the Moon, hot enough to cause the water to swell but not hot enough to evaporate it.

He recorded observations on both earthquakes and volcanoes, including accounts of the eruptions of the volcanoes in the Aeolian Islands, north of Sicily.

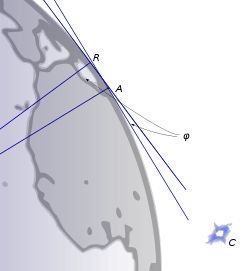

Earth's circumference

Posidonius calculated the Earth's circumference by reference to the position of the star Canopus. As explained by Cleomedes, Posidonius observed Canopus on but never above the horizon at Rhodes, while at Alexandria he saw it ascend as far as 7½ degrees above the horizon (the meridian arc between the latitude of the two locales is actually 5 degrees 14 minutes). Since he thought Rhodes was 5,000 stadia due north of Alexandria, and the difference in the star's elevation indicated the distance between the two locales was 1/48 of the circle, he multiplied 5,000 by 48 to arrive at a figure of 240,000 stadia for the circumference of the Earth.[13]

Translating stadia into modern units of distance can be problematic, but it is generally thought that the stadium used by Posidonius was almost exactly 1/10 of a modern statute mile. Thus Posidonius's measure of 240,000 stadia translates to 24,000 mi (39,000 km), not much short of the actual circumference of 24,901 mi (40,074 km).[13]

Posidonius was informed in his approach to finding the Earth's circumference by Eratosthenes, who a century earlier arrived at a figure of 252,000 stadia; both men's figures for the Earth's circumference were uncannily accurate.

Strabo noted that the distance between Rhodes and Alexandria is 3,750 stadia, and reported Posidonius's estimate of the Earth's circumference to be 180,000 stadia or 18,000 mi (29,000 km).[14] Pliny the Elder mentions Posidonius among his sources and without naming him reported his method for estimating the Earth's circumference. He noted, however, that Hipparchus had added some 26,000 stadia to Eratosthenes's estimate. The smaller value offered by Strabo and the different lengths of Greek and Roman stadia have created a persistent confusion around Posidonius's result. Ptolemy used Posidonius's lower value of 180,000 stades (about 33% too low) for the Earth's circumference in his Geography. This was the number used by Christopher Columbus to underestimate the distance to India as 70,000 stades.[15]

Meteorology

Posidonius in his writings on meteorology followed Aristotle. He theorized on the causes of clouds, mist, wind, and rain as well as frost, hail, lightning, and rainbows. He also estimated that the boundary between the clouds and the heavens lies about 40 stadia above the Earth.

Mathematics

Posidonius was one of the first to attempt to prove Euclid's fifth postulate of geometry. He suggested changing the definition of parallel straight lines to an equivalent statement that would allow him to prove the fifth postulate. From there, Euclidean geometry could be restructured, placing the fifth postulate among the theorems instead.[16]

In addition to his writings on geometry, Posidonius was credited for creating some mathematical definitions, or for articulating views on technical terms, for example 'theorem' and 'problem'.

History and tactics

In his Histories, Posidonius continued the World History of Polybius. His history of the period 146 – 88 BC is said to have filled 52 volumes.[17] His Histories continue the account of the rise and expansion of Roman dominance, which he appears to have supported. Posidonius did not follow Polybius's more detached and factual style, for Posidonius saw events as caused by human psychology; while he understood human passions and follies, he did not pardon or excuse them in his historical writing, using his narrative skill in fact to enlist the readers' approval or condemnation.

For Posidonius "history" extended beyond the earth into the sky; humanity was not isolated each in its own political history, but was a part of the cosmos. His Histories were not, therefore, concerned with isolated political history of peoples and individuals, but they included discussions of all forces and factors (geographical factors, mineral resources, climate, nutrition), which let humans act and be a part of their environment. For example, Posidonius considered the climate of Arabia and the life-giving strength of the sun, tides (taken from his book on the oceans), and climatic theory to explain people's ethnic or national characters.

Of Posidonius's work on tactics, The Art of War, the Greek historian Arrian complained that it was written 'for experts', which suggests that Posidonius may have had first hand experience of military leadership or, perhaps, used knowledge he gained from his acquaintance with Pompey.

On the Jews

Posidonius's writings on the Jews were probably the source of Diodorus Siculus's account of the siege of Jerusalem and possibly also for Strabo's.[18][19][20] Some of Posidonius's arguments are contested by Josephus in Against Apion.

Reputation and influence

In his own era, his writings on almost all the principal divisions of philosophy made Posidonius a renowned international figure throughout the Graeco-Roman world and he was widely cited by writers of his era, including Cicero, Livy, Plutarch, Strabo (who called Posidonius "the most learned of all philosophers of my time"), Cleomedes, Seneca the Younger, Diodorus Siculus (who used Posidonius as a source for his Bibliotheca historia ["Historical Library"]), and others. Although his ornate and rhetorical style of writing passed out of fashion soon after his death, Posidonius was acclaimed during his life for his literary ability and as a stylist.

Posidonius was the major source of materials on the Celts of Gaul and was profusely quoted by Timagenes, Julius Caesar, the Sicilian Greek Diodorus Siculus, and the Greek geographer Strabo.[21]

Posidonius appears to have moved with ease among the upper echelons of Roman society as an ambassador from Rhodes. He associated with some of the leading figures of late republican Rome, including Cicero and Pompey, both of whom visited him in Rhodes. In his twenties, Cicero attended his lectures (77 BC) and they continued to correspond. Cicero in his De Finibus closely followed Posidonius's presentation of Panaetius's ethical teachings.

Posidonius met Pompey when he was Rhodes's ambassador in Rome and Pompey visited him in Rhodes twice, once in 66 BC during his campaign against the pirates and again in 62 BC during his eastern campaigns, and asked Posidonius to write his biography. As a gesture of respect and great honor, Pompey lowered his fasces before Posidonius's door. Other Romans who visited Posidonius in Rhodes were Velleius, Cotta, and Lucilius.

Ptolemy was impressed by the sophistication of Posidonius's methods, which included correcting for the refraction of light passing through denser air near the horizon. Ptolemy's approval of Posidonius's result, rather than Eratosthenes's earlier and more correct figure, caused it to become the accepted value for the Earth's circumference for the next 1,500 years.

Posidonius fortified the Stoicism of the middle period with contemporary learning. Next to his teacher Panaetius, he did most, by writings and personal contacts, to spread Stoicism in the Roman world. A century later, Seneca referred to Posidonius as one of those who had made the largest contribution to philosophy.

His influence on philosophical thinking lasted until the Middle Ages, as is shown by citation in the Suda, the massive medieval lexicon.

At one time, scholars perceived Posidonius's influence in almost every subsequent writer, whether warranted or not. Today, Posidonius seems to be recognized as having had an inquiring and wide-ranging mind, not entirely original, but with a breadth of view that connected, in accordance with his underlying Stoic philosophy, all things and their causes and all knowledge into an overarching, unified world view.

The crater Posidonius on the Moon is named after him.

Death

Posidonius probably died in Rome or Rhodes in about 51 BC.

See also

References

- Sarton, George (1936). "The Unity and Diversity of the Mediterranean World". Osiris. 2: 406–463 [430]. doi:10.1086/368462.

- "Poseidonius", Encyclopædia Britannica, "Greek philosopher, considered the most learned man of his time and, possibly, of the entire Stoic school."

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 172.

- Magill, Frank Northen; Aves, Alison (1998). Dictionary of World Biography. Taylor & Francis. pp. 904–910. ISBN 9781579580407. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Posidonius, fragment 16 (quoted by Athenaeus, Book 4) and fragment 55 (quoted by Strabo, Book 4).

- Aristotle; Forster, E. S. (Edward Seymour), 1879–1950; Dobson, J. F. (John Frederic), 1875–1947 (1914). De Mundo. p. 1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kidd, I. G. Posidonius: The Translation of the Fragments, Volume III

- Diogenes Laërtius, The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, 7.39–40.

- Sextus Empiricus, Against the Professors, 7.19.

- Cicero. On Divination, ii. 42

- Posidonius. Fragment 215.K from Cleomedes

- Cicero. De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods), ii-34, p. 287.

- Posidonius, fragment 202

- Cleomedes (in Fragment 202) stated that if the distance is measured by some other number the result will be different, and using 3,750 instead of 5,000 produces this estimation: 3,750 x 48 = 180,000; see Fischer I., (1975), Another Look at Eratosthenes' and Posidonius' Determinations of the Earth's Circumference, Ql. J. of the Royal Astron. Soc., Vol. 16, p.152.

- John Freely, Before Galileo: The Birth of Modern Science in Medieval Europe (2012)

- Trudeau, Richard. The Non-Euclidean Revolution, Boston: Birkhauser, 1987, pp. 119–120.

- Article in 'Suda'

- Safrai, Shemuel; Stern, M. (1988), The Jewish people in the first century: Historical Geography, p. 1124,

Most scholars hold that Diodorus, from Book 33 of his work onwards, depended on Posidonius

- Gmirkin, Russell E. Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic histories, 2006, p. 54. "Jewish misanthropy was also a feature in Posidonius's account of the Jews, though in a less extreme form. 126 Diodorus Siculus, Library 40.3.4b likely derived from Posidonius, whose history may have been consulted by Pompey..."

- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel. The Image of the Jews in Greek Literature: The Hellenistic Period, 2009, p. 440. "Posidonius of apamea (d) The Anti-Jewish Libels and Accusations in Diodorus and Apion We have seen in chapters 11–12 that Posidonius used Moses and Mosaic Judaism to portray his own religious, social, and political ideals."

- Berresford Ellis, Peter (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-7867-1211-2.

- Sources

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 172.

- Bevan, Edwyn. Stoics and Skeptics, 1913. ISBN 0-89005-364-2

- Harley, J. B. & Woodward, David. The History of Cartography, Volume 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean, 1987, pp. 168–170. ISBN 0-226-31633-5 (v. 1)

- Ian G. Kidd and Ludwig Edelstein (eds.), Posidonius, The Fragments, vol. I, Cambridge University Press, 1972. ISBN 0-521-08046-0

- Ian G. Kidd, The Commentary, Vol. II.1 ISBN 0-521-20062-8 and II.2, 1988. ISBN 0-521-35498-6

- Ian G. Kidd, The Translation of the Fragments, vol. III, 1999. ISBN 0-521-60441-9

- Juergen Malitz, Poseidonios from Grosse Gestalten der griechischen Antike. 58 historische Portraits von Homer bis Kleopatra. Hrsg. von Kai Brodersen. München: Verlag C.H. Beck. S. 426–432.

- F. H. Sandbach, The Stoics, 2nd ed. ISBN 0-87220-253-4, 1994.

- Magill, Frank Northen; Aves, Alison (1998). Dictionary of World Biography. Taylor & Francis. pp. 904–910. ISBN 9781579580407. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

Further reading

- Freeman, Phillip, The Philosopher and the Druids: A Journey Among The Ancient Celts, Simon and Schuster, 2006.

- Irvine, William B. (2008) A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537461-2 — Discussion of his work and influence

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Posidonius |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Posidonius. |

- Posidonius of Rhodes (MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive)

- Poseidonius: English translations of fragments about history and geography

- World map according to Posidonius