Papyrus

Papyrus (/pəˈpaɪrəs/ pə-PYE-rəs) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, Cyperus papyrus, a wetland sedge.[1] Papyrus (plural: papyri) can also refer to a document written on sheets of such material, joined together side by side and rolled up into a scroll, an early form of a book.

Papyrus is first known to have been used in Egypt (at least as far back as the First Dynasty), as the papyrus plant was once abundant across the Nile Delta. It was also used throughout the Mediterranean region and in the Kingdom of Kush. Apart from a writing material, ancient Egyptians employed papyrus in the construction of other artifacts, such as reed boats, mats, rope, sandals, and baskets.[2]

History

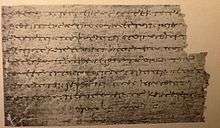

Papyrus was first manufactured in Egypt as far back as the fourth millennium BCE.[3][4][5] The earliest archaeological evidence of papyrus was excavated in 2012 and 2013 at Wadi al-Jarf, an ancient Egyptian harbor located on the Red Sea coast. These documents, the Diary of Merer, date from c. 2560–2550 BCE (end of the reign of Khufu).[4] The papyrus rolls describe the last years of building the Great Pyramid of Giza.[6] In the first centuries BCE and CE, papyrus scrolls gained a rival as a writing surface in the form of parchment, which was prepared from animal skins.[7] Sheets of parchment were folded to form quires from which book-form codices were fashioned. Early Christian writers soon adopted the codex form, and in the Græco-Roman world, it became common to cut sheets from papyrus rolls to form codices.

Codices were an improvement on the papyrus scroll, as the papyrus was not pliable enough to fold without cracking and a long roll, or scroll, was required to create large-volume texts. Papyrus had the advantage of being relatively cheap and easy to produce, but it was fragile and susceptible to both moisture and excessive dryness. Unless the papyrus was of perfect quality, the writing surface was irregular, and the range of media that could be used was also limited.

Papyrus was replaced in Europe by the cheaper, locally produced products parchment and vellum, of significantly higher durability in moist climates, though Henri Pirenne's connection of its disappearance with the Muslim conquest of Egypt is contested.[8] Its last appearance in the Merovingian chancery is with a document of 692, though it was known in Gaul until the middle of the following century. The latest certain dates for the use of papyrus are 1057 for a papal decree (typically conservative, all papal bulls were on papyrus until 1022), under Pope Victor II,[9] and 1087 for an Arabic document. Its use in Egypt continued until it was replaced by less expensive paper introduced by the Islamic world who originally learned of it from the Chinese. By the 12th century, parchment and paper were in use in the Byzantine Empire, but papyrus was still an option.[10]

Papyrus was made in several qualities and prices. Pliny the Elder and Isidore of Seville described six variations of papyrus which were sold in the Roman market of the day. These were graded by quality based on how fine, firm, white, and smooth the writing surface was. Grades ranged from the superfine Augustan, which was produced in sheets of 13 digits (10 inches) wide, to the least expensive and most coarse, measuring six digits (four inches) wide. Materials deemed unusable for writing or less than six digits were considered commercial quality and were pasted edge to edge to be used only for wrapping.[11]

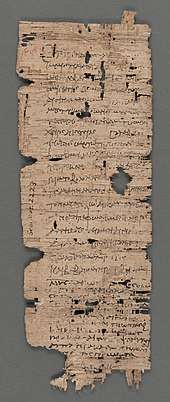

Until the middle of the 19th century, only some isolated documents written on papyrus were known, and museums simply displayed them as curiosities.[12] They did not contain literary works.[13] The first modern discovery of papyri rolls was made at Herculaneum in 1752. Until then, the only papyri known had been a few surviving from medieval times.[14][15] Scholarly investigations began with the Dutch historian Caspar Jacob Christiaan Reuvens (1793–1835). He wrote about the content of the Leyden papyrus, published in 1830. The first publication has been credited to the British scholar Charles Wycliffe Goodwin (1817–1878), who published for the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, one of the Papyri Graecae Magicae V, translated into English with commentary in 1853.[12]

Etymology

The English word "papyrus" derives, via Latin, from Greek πάπυρος (papyros),[16] a loanword of unknown (perhaps Pre-Greek) origin.[17] Greek has a second word for it, βύβλος (byblos),[18] said to derive from the name of the Phoenician city of Byblos. The Greek writer Theophrastus, who flourished during the 4th century BCE, uses papyros when referring to the plant used as a foodstuff and byblos for the same plant when used for nonfood products, such as cordage, basketry, or writing surfaces. The more specific term βίβλος biblos, which finds its way into English in such words as 'bibliography', 'bibliophile', and 'bible', refers to the inner bark of the papyrus plant. Papyrus is also the etymon of 'paper', a similar substance.

In the Egyptian language, papyrus was called wadj (w3ḏ), tjufy (ṯwfy), or djet (ḏt).

Documents written on papyrus

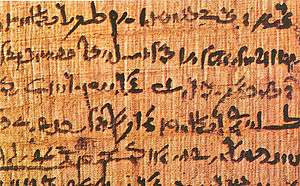

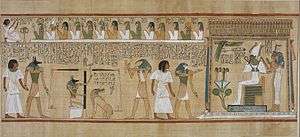

The word for the material papyrus is also used to designate documents written on sheets of it, often rolled up into scrolls. The plural for such documents is papyri. Historical papyri are given identifying names — generally the name of the discoverer, first owner or institution where they are kept—and numbered, such as "Papyrus Harris I". Often an abbreviated form is used, such as "pHarris I". These documents provide important information on ancient writings; they give us the only extant copy of Menander, the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Egyptian treatises on medicine (the Ebers Papyrus) and on surgery (the Edwin Smith papyrus), Egyptian mathematical treatises (the Rhind papyrus), and Egyptian folk tales (the Westcar papyrus). When, in the 18th century, a library of ancient papyri was found in Herculaneum, ripples of expectation spread among the learned men of the time. However, since these papyri were badly charred, their unscrolling and deciphering is still going on today.

Manufacture and use

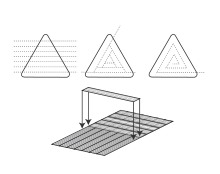

Papyrus is made from the stem of the papyrus plant, Cyperus papyrus. The outer rind is first removed, and the sticky fibrous inner pith is cut lengthwise into thin strips of about 40 cm (16 in) long. The strips are then placed side by side on a hard surface with their edges slightly overlapping, and then another layer of strips is laid on top at a right angle. The strips may have been soaked in water long enough for decomposition to begin, perhaps increasing adhesion, but this is not certain. The two layers possibly were glued together.[19] While still moist, the two layers are hammered together, mashing the layers into a single sheet. The sheet is then dried under pressure. After drying, the sheet is polished with some rounded object, possibly a stone or seashell or round hardwood.[20]

Sheets, or kollema, could be cut to fit the obligatory size or glued together to create a longer roll. The point where the kollema are joined with glue is called the kollesis. A wooden stick would be attached to the last sheet in a roll, making it easier to handle.[21] To form the long strip scrolls required, a number of such sheets were united, placed so all the horizontal fibres parallel with the roll's length were on one side and all the vertical fibres on the other. Normally, texts were first written on the recto, the lines following the fibres, parallel to the long edges of the scroll. Secondarily, papyrus was often reused, writing across the fibres on the verso.[5] Pliny the Elder describes the methods of preparing papyrus in his Naturalis Historia.

In a dry climate, like that of Egypt, papyrus is stable, formed as it is of highly rot-resistant cellulose; but storage in humid conditions can result in molds attacking and destroying the material. Library papyrus rolls were stored in wooden boxes and chests made in the form of statues. Papyrus scrolls were organized according to subject or author, and identified with clay labels that specified their contents without having to unroll the scroll.[22] In European conditions, papyrus seems to have lasted only a matter of decades; a 200-year-old papyrus was considered extraordinary. Imported papyrus once commonplace in Greece and Italy has since deteriorated beyond repair, but papyri are still being found in Egypt; extraordinary examples include the Elephantine papyri and the famous finds at Oxyrhynchus and Nag Hammadi. The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, containing the library of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Julius Caesar's father-in-law, was preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, but has only been partially excavated.

Sporadic attempts to revive the manufacture of papyrus have been made since the mid-18th century. Scottish explorer James Bruce experimented in the late 18th century with papyrus plants from the Sudan, for papyrus had become extinct in Egypt. Also in the 18th century, Sicilian Saverio Landolina manufactured papyrus at Syracuse, where papyrus plants had continued to grow in the wild. During the 1920s, when Egyptologist Battiscombe Gunn lived in Maadi, outside Cairo, he experimented with the manufacture of papyrus, growing the plant in his garden. He beat the sliced papyrus stalks between two layers of linen, and produced successful examples of papyrus, one of which was exhibited in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[23][24] The modern technique of papyrus production used in Egypt for the tourist trade was developed in 1962 by the Egyptian engineer Hassan Ragab using plants that had been reintroduced into Egypt in 1872 from France. Both Sicily and Egypt have centres of limited papyrus production.

Papyrus is still used by communities living in the vicinity of swamps, to the extent that rural householders derive up to 75% of their income from swamp goods.[25] Particularly in East and Central Africa, people harvest papyrus, which is used to manufacture items that are sold or used locally. Examples include baskets, hats, fish traps, trays or winnowing mats, and floor mats.[26] Papyrus is also used to make roofs, ceilings, rope and fences. Although alternatives, such as eucalyptus, are increasingly available, papyrus is still used as fuel.[25]

Collections of papyri

- Amherst Papyri: This is a collection of William Tyssen-Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst of Hackney. It includes biblical manuscripts, early church fragments, and classical documents from the Ptolemaic, Roman, and Byzantine eras. The collection was edited by Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt in 1900–1901. It is housed at the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York).

- Archduke Rainer Papyri: One of the world's largest collection of papyri (about 180,000 objects) in the Austrian National Library.[27]

- Berlin Papyri: housed in the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection.[28]

- Berliner griechische Urkunden: BGU, a publishing project ongoing since 1895

- Bodmer Papyri: This collection was purchased by Martin Bodmer in 1955–1956. Currently it is housed in the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana in Cologny. It includes Greek and Coptic documents, classical texts, biblical books, and writing of the early churches.

- Brooklyn Papyrus: This papyrus focuses mainly on snakebites and its remedies. It speaks of remedial methods for poisons obtained from snakes, scorpions, and tarantulas. The Brooklyn Papyrus currently resides in the Brooklyn Museum.[29]

- Chester Beatty Papyri: collection of 11 codices acquired by Alfred Chester Beatty in 1930–1931 and 1935. It is housed at the Chester Beatty Library. The collection was edited by Frederic G. Kenyon.

- Colt Papyri: it is housed at the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York).

- The Herculaneum papyri: These papyri were found in Herculaneum in the eighteenth century, carbonized by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. After some tinkering, a method was found to unroll and to read them. Most of them are housed at the Naples National Archaeological Museum.[30]

- The Heroninos Archive is a collection of around a thousand papyrus documents, dealing with the management of a large Roman estate, dating to the third century CE, found at the very end of the 19th century at Kasr El Harit, the site of ancient Theadelphia, in the Faiyum area of Egypt by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt. It is spread over many collections throughout the world.

- The Houghton's papyri: the collection at Houghton Library, Harvard University was acquired between 1901 and 1909 thanks to a donation from the Egypt Exploration Fund.[31]

- Saite Oracle Papyrus: This papyrus located at the Brooklyn Museum records the petition of a man named Pemou on behalf of his father, Harsiese to ask their god for permission to change temples.

- Martin Schøyen Collection: biblical manuscripts in Greek and Coptic, Dead Sea Scrolls, classical documents

- Michigan Papyrus Collection: this collection contains above 10 000 papyri fragments. It is housed at the University of Michigan.

- Oxyrhynchus Papyri: these numerous papyri fragments were discovered by Grenfell and Hunt in and around Oxyrhynchus. The publication of these papyri is still in progress. A large part of the Oxyrhynchus papyri are housed at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, others in the British Museum in London, in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and many other places.

- Princeton Papyri: it is housed at the Princeton University[32]

- Papiri della Società Italiana (PSI): a series, still in progress, published by the Società per la ricerca dei Papiri greci e latini in Egitto and from 1927 onwards by the succeeding Istituto Papirologico "G. Vitelli" in Florence. These papyri are situated at the institute itself and in the Biblioteca Laurenziana.

- Rylands Papyri: this collection contains above 700 papyri, with 31 ostraca and 54 codices. It is housed at the John Rylands University Library.

- Tebtunis Papyri: housed by the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, this is a collection of more than 30,000 fragments dating from the 3rd century BCE through the 3rd century CE, found in the winter 1899–1900 at the site of ancient Tebtunis, Egypt, by an expedition team led by the British papyrologists Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt.[33]

- Washington University Papyri Collection: includes 445 manuscript fragments, dating from the first century BCE to the eighth century AD. Housed at the Washington University Libraries.

- Will of Naunakhte: found at Deir el-Medina and dating to the 20th dynasty, it is notable because it is a legal document for a non-noble woman.[34]

- Yale Papyrus Collection: numbers over six thousand inventoried items and is cataloged, digitally scanned, and accessible online for close study. It is housed at the Beinecke Library.

Papyrus art

_(14780745242).jpg)

Other ancient writing materials:

- Palm leaf manuscript (India)

- Amate (Mesoamerica)

- Paper

- Ostracon

- Wax tablets

- Clay tablets

- Birch bark document

- Parchment

See also

- Pliny the Elder

- Papyrology

- Papyrus sanitary pad

- Palimpsest

- For Egyptian papyri:

- Other papyri:

- The papyrus plant in Egyptian art

References

Citations

- "Papyrus definition". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- "Ebers Papyrus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- Houston, Keith, The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of our Time, W. W. Norton & Company, 2016, pp.4-8 excerpt

- Tallet, Pierre (2012). "Ayn Sukhna and Wadi el-Jarf: Two newly discovered pharaonic harbours on the Suez Gulf" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan. 18: 147–68. ISSN 2049-5021. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- H. Idris Bell and T.C. Skeat, 1935. "Papyrus and its uses" (British Museum pamphlet). Archived 18 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Stille, Alexander. "The World's Oldest Papyrus and What It Can Tell Us About the Great Pyramids". Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Černý, Jaroslav. 1952. Paper and Books in Ancient Egypt: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered at University College London, 29 May 1947. London: H. K. Lewis. (Reprinted Chicago: Ares Publishers Inc., 1977).

- Pirenne, Mohammed and Charlemagne, critiqued by R.S. Lopez, "Mohammed and Charlemagne: a revision", Speculum (1943:14–38.).

- David Diringer, The Book before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental, Dover Publications, New York 1982, p. 166.

- Bompaire, Jacques and Jean Irigoin. La paleographie grecque et byzantine, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1977, 389 n. 6, cited in Alice-Mary Talbot (ed.). Holy women of Byzantium, Dumbarton Oaks, 1996, p. 227. ISBN 0-88402-248-X.

- Lewis, N (1983). "Papyrus and Ancient Writing: The First Hundred Years of Papyrology". Archaeology. 36 (4): 31–37.

- Hans Dieter Betz (1992). The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells, Volume 1.

- Frederic G. Kenyon, Palaeography of Greek papyri (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1899), p. 1.

- Frederic G. Kenyon, Palaeography of Greek papyri (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1899), p. 3.

- Diringer, David (1982). The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 250–256. ISBN 0-486-24243-9.

- πάπυρος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1151.

- βύβλος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Introduction to Greek and Latin Palaeography, Maunde Thompson. archive.org

- Bierbrier, Morris Leonard, ed. 1986. Papyrus: Structure and Usage. British Museum Occasional Papers 60, ser. ed. Anne Marriott. London: British Museum Press.

- Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles, California: Getty Publications. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-60606-083-4.

- Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Skyhorse. pp. 10–12. ISBN 9781602397064.

- Cerny, Jaroslav (1947). Paper and books in Ancient Egypt. London: H. K. Lewis & Co. Ltd.

- Lucas, A. (1934). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries, 2nd Ed. London: Edward Arnold and Co.

- Maclean, I.M.D., R. Tinch, M. Hassall and R.R. Boar. 2003c. "Towards optimal use of tropical wetlands: an economic evaluation of goods derived from papyrus swamps in southwest Uganda." Environmental Change and Management Working Paper No. 2003-10, Centre for Social and Economic Research into the Global Environment, University of East Anglia, Norwich.

- Langdon, S. 2000. Papyrus and its Uses in Modern Day Russia, Vol. 1, pp. 56–59.

- "Papyri". Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek.

- Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection

- "Ancient Egyptian Medical Papyri". Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Diringer, David (1982). The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental. New York: Dover Publications. p. 252 ff. ISBN 0-486-24243-9.

- "Digital Papyri at Houghton Library, Harvard University". Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- Digital Images of Selected Princeton Papyri

- The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri

- Černý, Jaroslav. "The Will of Naunakhte and the Related Documents." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 31 (1945): 29–53. doi:10.1177/030751334503100104. JSTOR 3855381.

Sources

- Leach, Bridget, and William John Tait. 2000. "Papyrus". In Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 227–253. Thorough technical discussion with extensive bibliography.

- Leach, Bridget, and William John Tait. 2001. "Papyrus". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 3 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 22–24.

- Parkinson, Richard Bruce, and Stephen G. J. Quirke. 1995. Papyrus. Egyptian Bookshelf. London: British Museum Press. General overview for a popular reading audience.

Further reading

- Horst Blanck: Das Buch in der Antike. Beck, München 1992, ISBN 3-406-36686-4

- Rosemarie Drenkhahn: Papyrus. In: Wolfgang Helck, Wolfhart Westendorf (eds.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie. vol. IV, Wiesbaden 1982, Spalte 667–670

- David Diringer, The Book before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental, Dover Publications, New York 1982, pp. 113–169, ISBN 0-486-24243-9.

- Victor Martin (Hrsg.): Ménandre. Le Dyscolos. Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, Cologny – Genève 1958

- Otto Mazal: Griechisch-römische Antike. Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1999, ISBN 3-201-01716-7 (Geschichte der Buchkultur; vol. 1)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Papyrus. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Papyri. |

- Leuven Homepage of Papyrus Collections

- Ancient Egyptian Papyrus – Aldokkan

- Yale Papyrus Collection Database at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Lund University Library Papyrus Collection

- Ghent University Library Papyrus Collection

- How Papyrus Paper is being made

- Thompson, Edward Maunde (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 743–745.

- "Papyri.info Resource and Partner Organizations". papyri.info. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Finding aid to the Advanced Papyrological Information System records at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.