Tile

A tile is a thin object usually square or rectangular in shape. Tile is a manufactured piece of hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass, generally used for covering roofs, floors, walls, or other objects such as tabletops. Alternatively, tile can sometimes refer to similar units made from lightweight materials such as perlite, wood, and mineral wool, typically used for wall and ceiling applications. In another sense, a tile is a construction tile or similar object, such as rectangular counters used in playing games (see tile-based game). The word is derived from the French word tuile, which is, in turn, from the Latin word tegula, meaning a roof tile composed of fired clay.

Tiles are often used to form wall and floor coverings, and can range from simple square tiles to complex or mosaics. Tiles are most often made of ceramic, typically glazed for internal uses and unglazed for roofing, but other materials are also commonly used, such as glass, cork, concrete and other composite materials, and stone. Tiling stone is typically marble, onyx, granite or slate. Thinner tiles can be used on walls than on floors, which require more durable surfaces that will resist impacts.

Decorative tile work and coloured brick

Decorative tilework or tile art should be distinguished from mosaic, where forms are made of great numbers of tiny irregularly positioned tesserae, each of a single color, usually of glass or sometimes ceramic or stone.

History

Ancient Middle East

The earliest evidence of glazed brick is the discovery of glazed bricks in the Elamite Temple at Chogha Zanbil, dated to the 13th century BC. Glazed and colored bricks were used to make low reliefs in Ancient Mesopotamia, most famously the Ishtar Gate of Babylon (ca. 575 BC), now partly reconstructed in Berlin, with sections elsewhere. Mesopotamian craftsmen were imported for the palaces of the Persian Empire such as Persepolis.

The use of sun-dried bricks or adobe was the main method of building in Mesopotamia where river mud was found in abundance along the Tigris and Euphrates. Here the scarcity of stone may have been an incentive to develop the technology of making kiln-fired bricks to use as an alternative. To strengthen walls made from sun-dried bricks, fired bricks began to be used as an outer protective skin for more important buildings like temples, palaces, city walls and gates. Making fired bricks is an advanced pottery technique. Fired bricks are solid masses of clay heated in kilns to temperatures of between 950° and 1,150°C, and a well-made fired brick is an extremely durable object. Like sun-dried bricks they were made in wooden molds but for bricks with relief decorations special molds had to be made.

Ancient Indian subcontinent

Rooms with tiled floors made of clay decorated with geometric circular patterns have been discovered from the ancient remains of Kalibangan, Balakot and Ahladino[1][2]

Tiling was used in the second century by the Sinhalese kings of ancient Sri Lanka, using smoothed and polished stone laid on floors and in swimming pools. Historians consider the techniques and tools for tiling as well advanced, evidenced by the fine workmanship and close fit of the tiles. Tiling from this period can be seen in Ruwanwelisaya and Kuttam Pokuna in the city of Anuradhapura.

Ancient Iran

The Achaemenid Empire decorated buildings with glazed brick tiles, including Darius the Great's palace at Susa, and buildings at Persepolis.[3]

The succeeding Sassanid Empire used tiles patterned with geometric designs, flowers, plants, birds and human beings, glazed up to a centimeter thick.[3]

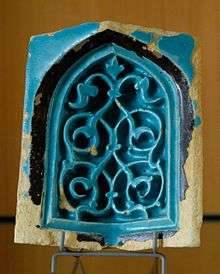

Islamic

Early Islamic mosaics in Iran consist mainly of geometric decorations in mosques and mausoleums, made of glazed brick. Typical turquoise tiling becomes popular in 10th-11th century and is used mostly for Kufic inscriptions on mosque walls. Seyyed Mosque in Isfahan (AD 1122), Dome of Maraqeh (AD 1147) and the Jame Mosque of Gonabad (1212 AD) are among the finest examples.[3] The dome of Jame' Atiq Mosque of Qazvin is also dated to this period.

The golden age of Persian tilework began during the Timurid Empire. In the moraq technique, single-color tiles were cut into small geometric pieces and assembled by pouring liquid plaster between them. After hardening, these panels were assembled on the walls of buildings. But the mosaic was not limited to flat areas. Tiles were used to cover both the interior and exterior surfaces of domes. Prominent Timurid examples of this technique include the Jame Mosque of Yazd (AD 1324–1365), Goharshad Mosque (AD 1418), the Madrassa of Khan in Shiraz (AD 1615), and the Molana Mosque (AD 1444).[3]

Other important tile techniques of this time include girih tiles, with their characteristic white girih, or straps.

Mihrabs, being the focal points of mosques, were usually the places where most sophisticated tilework was placed. The 14th-century mihrab at Madrasa Imami in Isfahan is an outstanding example of aesthetic union between the Islamic calligrapher's art and abstract ornament. The pointed arch, framing the mihrab's niche, bears an inscription in Kufic script used in 9th-century Qur'an.[4]

One of the best known architectural masterpieces of Iran is the Shah Mosque in Isfahan, from the 17th century. Its dome is a prime example of tile mosaic and its winter praying hall houses one of the finest ensembles of cuerda seca tiles in the world. A wide variety of tiles had to be manufactured in order to cover complex forms of the hall with consistent mosaic patterns. The result was a technological triumph as well as a dazzling display of abstract ornament.[4]

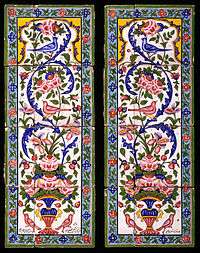

During the Safavid period, mosaic ornaments were often replaced by a haft rang (seven colors) technique. Pictures were painted on plain rectangle tiles, glazed and fired afterwards. Besides economic reasons, the seven colors method gave more freedom to artists and was less time-consuming. It was popular until the Qajar period, when the palette of colors was extended by yellow and orange.[3] The seven colors of Haft Rang tiles were usually black, white, ultramarine, turquoise, red, yellow and fawn.

The Persianate tradition continued and spread to much of the Islamic world, notably the İznik pottery of Turkey under the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries. Palaces, public buildings, mosques and türbe mausoleums were heavily decorated with large brightly colored patterns, typically with floral motifs, and friezes of astonishing complexity, including floral motifs and calligraphy as well as geometric patterns.

- Enderun library, Topkapi Palace

- Window Apartments of the Crown Prince, Topkapi Palace

Islamic buildings in Bukhara in central Asia (16th-17th century) also exhibit very sophisticated floral ornaments. In South Asia monuments and shrines adorned with Kashi tile work from Persia became a distinct feature of the shrines of Multan and Sindh. The Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore stands out as one of the masterpieces of Kashi time work from the Mughal period.

The zellige tradition of Arabic North Africa uses small colored tiles of various shapes to make very complex geometric patterns. It is halfway to mosaic, but as the different shapes must be fitted precisely together, it falls under tiling. The use of small coloured glass fields also make it rather like enamelling, but with ceramic rather than metal as the support.

Azulejos are derived from zellige, and the name is likewise derived. The term is both a simple Portuguese and Spanish term for zellige, and a term for later tilework following the tradition. Some azujelos are small-scale geometric patterns or vegetative motifs, some are blue monochrome and highly pictorial, and some are neither. The Baroque period produced extremely large painted scenes on tiles, usually in blue and white, for walls. Azulejos were also used in Latin American architecture.

Quadra (architecture) of St. John the Baptist covered with azulejos in carpet style (17th c.); Museu da Reinha D. Leonor; Beja, Portugal.

Quadra (architecture) of St. John the Baptist covered with azulejos in carpet style (17th c.); Museu da Reinha D. Leonor; Beja, Portugal. The Battle of Buçaco, depicted in azulejos.

The Battle of Buçaco, depicted in azulejos.

Medieval influences between Middle Eastern tilework and tilework in Europe were mainly through Islamic Iberia and the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires. The Alhambra zellige are said to have inspired the tessellations of M. C. Escher.

Medieval encaustic tiles were made of multiple colours of clay, shaped and baked together to form a patternt that, rather than sitting on the surface, ran right through the thickness of the tile, and thus would not wear away.

Medieval Europe

Medieval Europe made considerable use of painted tiles, sometimes producing very elaborate schemes, of which few have survived. Religious and secular stories were depicted. The imaginary tiles with Old Testament scenes shown on the floor in Jan van Eyck's 1434 Annunciation in Washington are an example. The 14th century "Tring tiles" in the British Museum show childhood scenes from the Life of Christ, possibly for a wall rather than a floor,[5] while their 13th century "Chertsey Tiles", though from an abbey, show scenes of Richard the Lionheart battling with Saladin in very high-quality work.[6] Medieval letter tiles were used to create Christian inscriptions on church floors.

Delftware wall tiles, typically with a painted design covering only one (rather small) blue and white tile, were ubiquitous in Holland and widely exported over Northern Europe from the 16th century on, replacing many local industries. Several 18th century royal palaces had porcelain rooms with the walls entirely covered in porcelain in tiles or panels. Surviving examples include ones at Capodimonte, Naples, the Royal Palace of Madrid and the nearby Royal Palace of Aranjuez.

Far East

There are several other types of traditional tiles that remain in manufacture, for example the small, almost mosaic, brightly colored zellige tiles of Morocco and the surrounding countries. With exceptions, notably the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, decorated tiles or glazed bricks do not feature largely in East Asian ceramics.

Modern Europe

The Victorian period saw a great revival in tilework, largely as part of the Gothic Revival, but also the Arts and Crafts Movement. Patterned tiles, or tiles making up patterns, were now mass-produced by machine and reliably level for floors and cheap to produce, especially for churches, schools and public buildings, but also for domestic hallways and bathrooms. For many uses the tougher encaustic tile was used. Wall tiles in various styles also revived; the rise of the bathroom contributing greatly to this, as well as greater appreciation of the benefit of hygiene in kitchens. William De Morgan was the leading English designer working in tiles, strongly influenced by Islamic designs.

Since the Victorian period tiles have remained standard for kitchens and bathrooms, and many types of public area.

.jpg)

Portugal and São Luís continue their tradition of azulejo tilework today, with azulejos used to decorate buildings, ships,[7] and even rocks.

Roof tiles

Roof tiles are designed mainly to keep out rain and heat, and are traditionally made from locally available materials such as clay, granite, terracotta or slate. Modern materials such as concrete, glass and plastic are also used and some clay tiles have a waterproof glaze. A large number of shapes (or "profiles") of roof tiles have evolved.

Floor tiles

These are commonly made of ceramic or stone, although recent technological advances have resulted in rubber or glass tiles for floors as well. Ceramic tiles may be painted and glazed. Small mosaic tiles may be laid in various patterns. Floor tiles are typically set into mortar consisting of sand, cement and often a latex additive for extra adhesion. The spaces between the tiles are commonly filled with sanded or unsanded floor grout, but traditionally mortar was used.

Natural stone tiles can be beautiful but as a natural product they are less uniform in color and pattern, and require more planning for use and installation. Mass-produced stone tiles are uniform in width and length. Granite or marble tiles are sawn on both sides and then polished or finished on the top surface so that they have a uniform thickness. Other natural stone tiles such as slate are typically "riven" (split) on the top surface so that the thickness of the tile varies slightly from one spot on the tile to another and from one tile to another. Variations in tile thickness can be handled by adjusting the amount of mortar under each part of the tile, by using wide grout lines that "ramp" between different thicknesses, or by using a cold chisel to knock off high spots.

Some stone tiles such as polished granite, marble, and travertine are very slippery when wet. Stone tiles with a riven (split) surface such as slate or with a sawn and then sandblasted or honed surface will be more slip-resistant. Ceramic tiles for use in wet areas can be made more slip-resistant either by using very small tiles so that the grout lines acts as grooves or by imprinting a contour pattern onto the face of the tile.

The hardness of natural stone tiles varies such that some of the softer stone (e.g. limestone) tiles are not suitable for very heavy-traffic floor areas. On the other hand, ceramic tiles typically have a glazed upper surface and when that becomes scratched or pitted the floor looks worn, whereas the same amount of wear on natural stone tiles will not show, or will be less noticeable.

Natural stone tiles can be stained by spilled liquids; they must be sealed and periodically resealed with a sealant in contrast to ceramic tiles which only need their grout lines sealed. However, because of the complex, nonrepeating patterns in natural stone, small amounts of dirt on many natural stone floor tiles do not show.

The tendency of floor tiles to stain depends not only on a sealant being applied, and periodically reapplied, but also on their porosity or how porous the stone is. Slate is an example of a less porous stone while limestone is an example of a more porous stone. Different granites and marbles have different porosities with the less porous ones being more valued and more expensive.

Most vendors of stone tiles emphasize that there will be variation in color and pattern from one batch of tiles to another of the same description and variation within the same batch. Stone floor tiles tend to be heavier than ceramic tiles and somewhat more prone to breakage during shipment.

Rubber floor tiles have a variety of uses, both in residential and commercial settings. They are especially useful in situations where it is desired to have high-traction floors or protection for an easily breakable floor. Some common uses include flooring of garage, workshops, patios, swimming pool decks, sport courts, gyms, and dance floors.

Plastic floor tiles including interlocking floor tiles that can be installed without adhesive or glue are a recent innovation and are suitable for areas subject to heavy traffic, wet areas and floors that are subject to movement, damp or contamination from oil, grease or other substances that may prevent adhesion to the substrate. Common uses include old factory floors, garages, gyms and sports complexes, schools and shops.

Ceiling tiles

Ceiling tiles are lightweight tiles used inside buildings. They are placed in an aluminium grid; they provide little thermal insulation but are generally designed either to improve the acoustics of a room or to reduce the volume of air being heated or cooled.

Mineral fiber tiles are fabricated from a range of products; wet felt tiles can be manufactured from perlite, mineral wool, and fibers from recycled paper; stone wool tiles are created by combining molten stone and binders which is then spun to create the tile; gypsum tiles are based on the soft mineral and then finished with vinyl, paper or a decorative face.

Ceiling tiles very often have patterns on the front face; these are there in most circumstances to aid with the tiles ability to improve acoustics.

Ceiling tiles also provide a barrier to the spread of smoke and fire. Breaking, displacing, or removing ceiling tiles enables hot gases and smoke from a fire to rise and accumulate above detectors and sprinklers. Doing so delays their activation, enabling fires to grow more rapidly.[8]

Ceiling tiles, especially in old Mediterranean houses, were made of terracotta and were placed on top of the wooden ceiling beams and upon those were placed the roof tiles. They were then plastered or painted, but nowadays are usually left bare for decorative purposes.

Modern-day tile ceilings may be flush mounted (nail up or glue up) or installed as dropped ceilings.

Materials and processes

Ceramic

Ceramic materials for tiles include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. Terracotta is a traditional material used for roof tiles.[9]

Porcelain tiles

This is a US term, and defined in ASTM standard C242 as a ceramic mosaic tile or paver that is generally made by dust-pressing and of a composition yielding a tile that is dense, fine-grained, and smooth, with sharply-formed face, usually impervious. The colours of such tiles are generally clear and bright.[10]

Pebble

Similar to mosaics or other patterned tiles, pebble tiles are tiles made up of small pebbles attached to a backing. The tile is generally designed in an interlocking pattern so that final installations fit of multiple tiles fit together to have a seamless appearance. A relatively new tile design, pebble tiles were originally developed in Indonesia using pebbles found in various locations in the country. Today, pebble tiles feature all types of stones and pebbles from around the world.

Digital printed

Printing techniques and digital manipulation of art and photography are used in what is known as "custom tile printing". Dye sublimation printers, inkjet printers and ceramic inks and toners permit printing on a variety of tile types yielding photographic-quality reproduction.[11] Using digital image capture via scanning or digital cameras, bitmap/raster images can be prepared in photo editing software programs. Specialized custom-tile printing techniques permit transfer under heat and pressure or the use of high temperature kilns to fuse the picture to the tile substrate. This has become a method of producing custom tile murals for kitchens, showers, and commercial decoration in restaurants, hotels, and corporate lobbies.

Diamond etched

A method for custom tile printing involving a diamond-tipped drill controlled by a computer. Compared with the laser engravings, diamond etching is in almost every circumstance more permanent.

Mathematics of tiling

Certain shapes of tiles, most obviously rectangles, can be replicated to cover a surface with no gaps. These shapes are said to tessellate (from the Latin tessella, 'tile') and such a tiling is called a tessellation. Geometric patterns of some Islamic polychrome decorative tilings are rather complicated (see Islamic geometric patterns and, in particular, Girih tiles), even up to supposedly quaziperiodic ones, similar to Penrose tilings.

Further reading

- Carboni, S. & Masuya, T. (1993). Persian tiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Marilyn Y. Goldberg, "Greek Temples and Chinese Roofs," American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 87, No. 3. (Jul. 1983), pp. 305–310

- Örjan Wikander, "Archaic Roof Tiles the First Generations," Hesperia, Vol. 59, No. 1. (Jan.–Mar. 1990), pp. 285–290

- William Rostoker; Elizabeth Gebhard, "The Reproduction of Rooftiles for the Archaic Temple of Poseidon at Isthmia, Greece," Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 8, No. 2. (Summer, 1981), pp. 211–227

- Michel Kornmann and CTTB, "Clay bricks and roof tiles, manufacturing and properties", Soc. Industrie Minerale, Paris (2007) ISBN 2-9517765-6-X

- E-book on the manufacture of roofing tiles in the United States from 1910.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiles. |

- Building integrated photovoltaics

- Dimension stone

- Dropped ceiling

- Glass tile

- Marble

- Porcelain tile

- Quarry tile

- Roof shingle

- Tile mural

- Vitrified tile

References

- Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. 1926. ISBN 9781259063237.

kalibangan tiles.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079072.

- Iran: Visual Arts: history of Iranian Tile Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Iran Chamber Society

- Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner's Art Through The Ages, A Global History. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-495-41059-1.

- Tring Tiles Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine British Museum

- Chertsey Tiles Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, British Museum

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Missing Ceiling Tiles. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress Office of Compliance, 2008.

- Maldonado, Eduardo (19 November 2014). Environmentally Friendly Cities: Proceedings of Plea 1998, Passive and Low Energy Architecture, 1998, Lisbon, Portugal, June 1998. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-25622-8. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018.

- Dictionary of Ceramics. A.Dodd. Institute of Materials/Pergamon Press. 1994.

- "Inkjet Decoration of Ceramic Tiles". digitalfire.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

| Look up tile in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

.jpg)

%2C_in_Bucharest_(Romania).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)