Psychopathy

Psychopathy, sometimes considered synonymous with sociopathy, is traditionally a personality disorder characterized by persistent antisocial behavior, impaired empathy and remorse, and bold, disinhibited, and egotistical traits.[1][2][3] Different conceptions of psychopathy have been used throughout history that are only partly overlapping and may sometimes be contradictory.[4]

| Psychopathy | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| Symptoms | Boldness, high self-esteem, lack of empathy, inclination to violence and manipulation, impulsivity |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental |

| Risk factors | Family history, poverty, being neglected by parents |

| Differential diagnosis | Sociopathy, Narcissism, Borderline personality disorder, Bipolar disorder (mania) |

| Prognosis | Poor |

| Frequency | 1% of general population |

| Personality disorders |

|---|

| Cluster A (odd) |

| Cluster B (dramatic) |

| Cluster C (anxious) |

| Not specified |

Hervey M. Cleckley, an American psychiatrist, influenced the initial diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality reaction/disturbance in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), as did American psychologist George E. Partridge.[5] The DSM and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) subsequently introduced the diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and dissocial personality disorder (DPD) respectively, stating that these diagnoses have been referred to (or include what is referred to) as psychopathy or sociopathy. The creation of ASPD and DPD was driven by the fact that many of the classic traits of psychopathy were impossible to measure objectively.[4][6][7][8][9] Canadian psychologist Robert D. Hare later repopularized the construct of psychopathy in criminology with his Psychopathy Checklist.[4][7][10][11]

Although no psychiatric or psychological organization has sanctioned a diagnosis titled "psychopathy", assessments of psychopathic characteristics are widely used in criminal justice settings in some nations and may have important consequences for individuals. The study of psychopathy is an active field of research, and the term is also used by the general public, popular press, and in fictional portrayals.[11][12] While the term is often employed in common usage along with "crazy", "insane", and "mentally ill", there is a categorical difference between psychosis and psychopathy.[13]

Definition

A person suffering from a chronic mental disorder with abnormal or violent social behavior.

Concepts

There are multiple conceptualizations of psychopathy,[4] including Cleckleyan psychopathy (Hervey Cleckley's conception entailing bold, disinhibited behavior, and "feckless disregard") and criminal psychopathy (a meaner, more aggressive and disinhibited conception explicitly entailing persistent and sometimes serious criminal behavior). The latter conceptualization is typically used as the modern clinical concept and assessed by the Psychopathy Checklist.[4] The label "psychopath" may have implications and stigma related to decisions about punishment severity for criminal acts, medical treatment, civil commitments, etc. Efforts have therefore been made to clarify the meaning of the term.[4]

The triarchic model[1] suggests that different conceptions of psychopathy emphasize three observable characteristics to various degrees. Analyses have been made with respect to the applicability of measurement tools such as the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL, PCL-R) and Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) to this model.[1][4]

- Boldness. Low fear including stress-tolerance, toleration of unfamiliarity and danger, and high self-confidence and social assertiveness. The PCL-R measures this relatively poorly and mainly through Facet 1 of Factor 1. Similar to PPI Fearless dominance. May correspond to differences in the amygdala and other neurological systems associated with fear.[1][4]

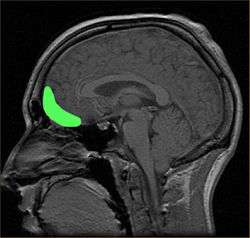

- Disinhibition. Poor impulse control including problems with planning and foresight, lacking affect and urge control, demand for immediate gratification, and poor behavioral restraints. Similar to PCL-R Factor 2 and PPI Impulsive antisociality. May correspond to impairments in frontal lobe systems that are involved in such control.[1][4]

- Meanness. Lacking empathy and close attachments with others, disdain of close attachments, use of cruelty to gain empowerment, exploitative tendencies, defiance of authority, and destructive excitement seeking. The PCL-R in general is related to this but in particular some elements in Factor 1. Similar to PPI, but also includes elements of subscales in Impulsive antisociality.[1][4]

Measurement

An early and influential analysis from Harris and colleagues indicated that a discrete category, or taxon, may underlie PCL-R psychopathy, allowing it to be measured and analyzed. However, this was only found for the behavioral Factor 2 items they identified, child problem behaviors; adult criminal behavior did not support the existence of a taxon.[14] Marcus, John, and Edens more recently performed a series of statistical analyses on PPI scores and concluded that psychopathy may best be conceptualized as having a "dimensional latent structure" like depression.[15]

Marcus et al. repeated the study on a larger sample of prisoners, using the PCL-R and seeking to rule out other experimental or statistical issues that may have produced the previously different findings.[16] They again found that the psychopathy measurements do not appear to be identifying a discrete type (a taxon). They suggest that while for legal or other practical purposes an arbitrary cut-off point on trait scores might be used, there is actually no clear scientific evidence for an objective point of difference by which to label some people "psychopaths"; in other words, a "psychopath" may be more accurately described as someone who is "relatively psychopathic".[4]

The PCL-R was developed for research, not clinical forensic diagnosis, and even for research purposes to improve understanding of the underlying issues, it is necessary to examine dimensions of personality in general rather than only a constellation of traits.[4][17]

Personality dimensions

Studies have linked psychopathy to alternative dimensions such as antagonism (high), conscientiousness (low) and anxiousness (low).[18]

Psychopathy has also been linked to high psychoticism—a theorized dimension referring to tough, aggressive or hostile tendencies. Aspects of this that appear associated with psychopathy are lack of socialization and responsibility, impulsivity, sensation-seeking (in some cases), and aggression.[19][20][21]

Otto Kernberg, from a particular psychoanalytic perspective, believed psychopathy should be considered as part of a spectrum of pathological narcissism, that would range from narcissistic personality on the low end, malignant narcissism in the middle, and psychopathy at the high end.[21]

Psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism, three personality traits that are together referred to as the dark triad, share certain characteristics, such as a callous-manipulative interpersonal style.[22] The dark tetrad refers to these traits with the addition of sadism.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Criticism of current conceptions

The current conceptions of psychopathy have been criticized for being poorly conceptualized, highly subjective, and encompassing a wide variety of underlying disorders. Dorothy Otnow Lewis has written[29]

"The concept and subsequent reification of the diagnosis “psychopathy” has, to this author’s mind, hampered the understanding of criminality and violence... According to Hare, in many cases one need not even meet the patient. Just rummage through his records to determine what items seemed to fit. Nonsense. To this writer’s mind, psychopathy and its synonyms (e.g., sociopathy and antisocial personality) are lazy diagnoses. Over the years the authors’ team has seen scores of offenders who, prior to evaluation by the authors, were dismissed as psychopaths or the like. Detailed, comprehensive psychiatric, neurological, and neuropsychological evaluations have uncovered a multitude of signs, symptoms, and behaviors indicative of such disorders as bipolar mood disorder, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, complex partial seizures, dissociative identity disorder, parasomnia, and, of course, brain damage/dysfunction."

Half of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist consists of symptoms of mania, hypomania, and frontal-lobe dysfunction, which frequently results in underlying disorders being dismissed.[30] Hare's conception of psychopathy has also been criticized for being reductionist, dismissive, tautological, and ignorant of context as well as the dynamic nature of human behavior.[31] Some have called for rejection of the concept altogether, due to its vague, subjective and judgmental nature that makes it prone to misuse.[32]

Signs and symptoms

Socially, psychopathy expresses extensive callous and manipulative self-serving behaviors with no regard for others, and often is associated with repeated delinquency, crime and violence. Mentally, impairments in processes related to affect and cognition, particularly socially related mental processes, have been found in those with the disorder. Developmentally, symptoms of psychopathy have been identified in young children with conduct disorder, and is suggestive of at least a partial constitutional factor that influences its development.[33]

Offending

Criminality

In terms of simple correlations, the PCL-R manual states an average score of 22.1 has been found in North American prisoner samples, and that 20.5% scored 30 or higher. An analysis of prisoner samples from outside North America found a somewhat lower average value of 17.5. Studies have found that psychopathy scores correlated with repeated imprisonment, detention in higher security, disciplinary infractions, and substance misuse.[34][35]

Psychopathy, as measured with the PCL-R in institutional settings, shows in meta-analyses small to moderate effect sizes with institutional misbehavior, postrelease crime, or postrelease violent crime with similar effects for the three outcomes. Individual studies give similar results for adult offenders, forensic psychiatric samples, community samples, and youth. The PCL-R is poorer at predicting sexual re-offending. This small to moderate effect appears to be due largely to the scale items that assess impulsive behaviors and past criminal history, which are well-established but very general risk factors. The aspects of core personality often held to be distinctively psychopathic generally show little or no predictive link to crime by themselves. For example, Factor 1 of the PCL-R and Fearless dominance of the PPI-R have smaller or no relationship to crime, including violent crime. In contrast, Factor 2 and Impulsive antisociality of the PPI-R are associated more strongly with criminality. Factor 2 has a relationship of similar strength to that of the PCL-R as a whole. The antisocial facet of the PCL-R is still predictive of future violence after controlling for past criminal behavior which, together with results regarding the PPI-R which by design does not include past criminal behavior, suggests that impulsive behaviors is an independent risk factor. Thus, the concept of psychopathy may perform poorly when attempted to be used as a general theory of crime.[4][36]

Violence

Studies have suggested a strong correlation between psychopathy scores and violence, and the PCL-R emphasizes features that are somewhat predictive of violent behavior. Researchers, however, have noted that psychopathy is dissociable from and not synonymous with violence.[4][37]

It has been suggested that psychopathy is associated with "instrumental", also known as predatory, proactive, or "cold blooded" aggression, a form of aggression characterized by reduced emotion and conducted with a goal differing from but facilitated by the commission of harm.[38][39] One conclusion in this regard was made by a 2002 study of homicide offenders, which reported that the homicides committed by homicidal offenders with psychopathy were almost always (93.3%) primarily instrumental, significantly more than the proportion (48.4%) of those committed by non-psychopathic homicidal offenders, with the instrumentality of the homicide also correlated with the total PCL-R score of the offender as well as their scores on the Factor 1 "interpersonal-affective" dimension. However, contrary to the equating of this to mean exclusively "in cold blood", more than a third of the homicides committed by psychopathic offenders involved some component of emotional reactivity as well.[40] In any case, FBI profilers indicate that serious victim injury is generally an emotional offense, and some research supports this, at least with regard to sexual offending. One study has found more serious offending by non-psychopathic offenders on average than by offenders with psychopathy (e.g. more homicides versus more armed robbery and property offenses) and another that the Affective facet of the PCL-R predicted reduced offense seriousness.[4]

Studies on perpetrators of domestic violence find that abusers have high rates of psychopathy, with the prevalence estimated to be at around 15-30%. Furthermore, the commission of domestic violence is correlated with Factor 1 of the PCL-R, which describes the emotional deficits and the callous and exploitative interpersonal style found in psychopathy. The prevalence of psychopathy among domestic abusers indicate that the core characteristics of psychopathy, such as callousness, remorselessness, and a lack of close interpersonal bonds, predispose those with psychopathy to committing domestic abuse, and suggest that the domestic abuses committed by these individuals are callously perpetrated (i.e. instrumentally aggressive) rather than a case of emotional aggression and therefore may not be amenable to the types of psychosocial interventions commonly given to domestic abuse perpetrators.[39][41]

Some clinicians suggest that assessment of the construct of psychopathy does not necessarily add value to violence risk assessment. A large systematic review and meta-regression found that the PCL performed the poorest out of nine tools for predicting violence. In addition, studies conducted by the authors or translators of violence prediction measures, including the PCL, show on average more positive results than those conducted by more independent investigators. There are several other risk assessment instruments which can predict further crime with an accuracy similar to the PCL-R and some of these are considerably easier, quicker, and less expensive to administer. This may even be done automatically by a computer simply based on data such as age, gender, number of previous convictions and age of first conviction. Some of these assessments may also identify treatment change and goals, identify quick changes that may help short-term management, identify more specific kinds of violence that may be at risk, and may have established specific probabilities of offending for specific scores. Nonetheless, the PCL-R may continue to be popular for risk assessment because of its pioneering role and the large amount of research done using it.[4][42][43][44][45][46][47]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation reports that psychopathic behavior is consistent with traits common to some serial killers, including sensation seeking, a lack of remorse or guilt, impulsivity, the need for control, and predatory behavior.[48] It has also been found that the homicide victims of psychopathic offenders were disproportionately female in comparison to the more equitable gender distribution of victims of non-psychopathic offenders.[40]

Sexual offending

Psychopathy has been associated with commission of sexual crime, with some researchers arguing that it is correlated with a preference for violent sexual behavior. A 2011 study of conditional releases for Canadian male federal offenders found that psychopathy was related to more violent and non-violent offences but not more sexual offences. For child molesters, psychopathy was associated with more offences.[49] A study on the relationship between psychopathy scores and types of aggression in a sample of sexual murderers, in which 84.2% of the sample had PCL-R scores above 20 and 47.4% above 30, found that 82.4% of those with scores above 30 had engaged in sadistic violence (defined as enjoyment indicated by self-report or evidence) compared to 52.6% of those with scores below 30, and total PCL-R and Factor 1 scores correlated significantly with sadistic violence.[50][51] Despite this, it is reported that offenders with psychopathy (both sexual and non-sexual offenders) are about 2.5 times more likely to be granted conditional release compared to non-psychopathic offenders.[49]

In considering the issue of possible reunification of some sex offenders into homes with a non-offending parent and children, it has been advised that any sex offender with a significant criminal history should be assessed on the PCL-R, and if they score 18 or higher, then they should be excluded from any consideration of being placed in a home with children under any circumstances.[52] There is, however, increasing concern that PCL scores are too inconsistent between different examiners, including in its use to evaluate sex offenders.[53]

Other offending

The possibility of psychopathy has been associated with organized crime, economic crime and war crimes. Terrorists are sometimes considered psychopathic, and comparisons may be drawn with traits such as antisocial violence, a selfish world view that precludes the welfare of others, a lack of remorse or guilt, and blame externalization. However, John Horgan, author of The Psychology of Terrorism, argues that such comparisons could also then be drawn more widely: for example, to soldiers in wars. Coordinated terrorist activity requires organization, loyalty and ideological fanaticism often to the extreme of sacrificing oneself for an ideological cause. Traits such as a self-centered disposition, unreliability, poor behavioral controls, and unusual behaviors may disadvantage or preclude psychopathic individuals in conducting organized terrorism.[54][55]

It may be that a significant portion of people with the disorder are socially successful and tend to express their antisocial behavior through more covert avenues such as social manipulation or white collar crime. Such individuals are sometimes referred to as "successful psychopaths", and may not necessarily always have extensive histories of traditional antisocial behavior as characteristic of traditional psychopathy.[56]

Childhood and adolescent precursors

The PCL:YV is an adaptation of the PCL-R for individuals aged 13–18 years. It is, like the PCL-R, done by a trained rater based on an interview and an examination of criminal and other records. The "Antisocial Process Screening Device" (APSD) is also an adaptation of the PCL-R. It can be administered by parents or teachers for individuals aged 6–13 years. High psychopathy scores for both juveniles, as measured with these instruments, and adults, as measured with the PCL-R and other measurement tools, have similar associations with other variables, including similar ability in predicting violence and criminality.[4][57][58] Juvenile psychopathy may also be associated with more negative emotionality such as anger, hostility, anxiety, and depression.[4][59] Psychopathic traits in youth typically comprise three factors: callous/unemotional, narcissism, and impulsivity/irresponsibility.[60][61]

There is positive correlation between early negative life events of the ages 0–4 and the emotion-based aspects of psychopathy.[62] There are moderate to high correlations between psychopathy rankings from late childhood to early adolescence. The correlations are considerably lower from early- or mid-adolescence to adulthood. In one study most of the similarities were on the Impulsive- and Antisocial-Behavior scales. Of those adolescents who scored in the top 5% highest psychopathy scores at age 13, less than one third (29%) were classified as psychopathic at age 24. Some recent studies have also found poorer ability at predicting long-term, adult offending.[4][63]

Conduct disorder

Conduct disorder is diagnosed based on a prolonged pattern of antisocial behavior in childhood and/or adolescence, and may be seen as a precursor to ASPD. Some researchers have speculated that there are two subtypes of conduct disorder which mark dual developmental pathways to adult psychopathy.[4][64][65] The DSM allows differentiating between childhood onset before age 10 and adolescent onset at age 10 and later. Childhood onset is argued to be more due to a personality disorder caused by neurological deficits interacting with an adverse environment. For many, but not all, childhood onset is associated with what is in Terrie Moffitt's developmental theory of crime referred to as "life-course- persistent" antisocial behavior as well as poorer health and economic status. Adolescent onset is argued to more typically be associated with short-term antisocial behavior.[4]

It has been suggested that the combination of early-onset conduct disorder and ADHD may be associated with life-course-persistent antisocial behaviors as well as psychopathy. There is evidence that this combination is more aggressive and antisocial than those with conduct disorder alone. However, it is not a particularly distinct group since the vast majority of young children with conduct disorder also have ADHD. Some evidence indicates that this group has deficits in behavioral inhibition, similar to that of adults with psychopathy. They may not be more likely than those with conduct disorder alone to have the interpersonal/affective features and the deficits in emotional processing characteristic of adults with psychopathy. Proponents of different types/dimensions of psychopathy have seen this type as possibly corresponding to adult secondary psychopathy and increased disinhibition in the triarchic model.[4]

The DSM-5 includes a specifier for those with conduct disorder who also display a callous, unemotional interpersonal style across multiple settings and relationships.[62] The specifier is based on research which suggests that those with conduct disorder who also meet criteria for the specifier tend to have a more severe form of the disorder with an earlier onset as well as a different response to treatment. Proponents of different types/dimensions of psychopathy have seen this as possibly corresponding to adult primary psychopathy and increased boldness and/or meanness in the triarchic model.[4][66]

Mental traits

Cognition

Dysfunctions in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala regions of the brain have been associated with specific learning impairments in psychopathy. Since the 1980s, scientists have linked traumatic brain injury, including damage to these regions, with violent and psychopathic behavior. Patients with damage in such areas resembled "psychopathic individuals" whose brains were incapable of acquiring social and moral knowledge; those who acquired damage as children may have trouble conceptualizing social or moral reasoning, while those with adult-acquired damage may be aware of proper social and moral conduct but be unable to behave appropriately. Dysfunctions in the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex may also impair stimulus-reinforced learning in psychopaths, whether punishment-based or reward-based. People scoring 25 or higher in the PCL-R, with an associated history of violent behavior, appear to have significantly reduced mean microstructural integrity in their uncinate fasciculus—white matter connecting the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex. There is evidence from DT-MRI, of breakdowns in the white matter connections between these two important areas.[67][68][69][70][71]

Although some studies have suggested inverse relationships between psychopathy and intelligence, including with regards to verbal IQ, Hare and Neumann state that a large literature demonstrates at most only a weak association between psychopathy and IQ, noting that the early pioneer Cleckley included good intelligence in his checklist due to selection bias (since many of his patients were "well educated and from middle-class or upper-class backgrounds") and that "there is no obvious theoretical reason why the disorder described by Cleckley or other clinicians should be related to intelligence; some psychopaths are bright, others less so". Studies also indicate that different aspects of the definition of psychopathy (e.g. interpersonal, affective (emotion), behavioral and lifestyle components) can show different links to intelligence, and the result can depend on the type of intelligence assessment (e.g. verbal, creative, practical, analytical).[12][37][72][73]

Emotion recognition and empathy

A large body of research suggests that psychopathy is associated with atypical responses to distress cues (e.g. facial and vocal expressions of fear and sadness), including decreased activation of the fusiform and extrastriate cortical regions, which may partly account for impaired recognition of and reduced autonomic responsiveness to expressions of fear, and impairments of empathy.[33] The underlying biological surfaces for processing expressions of happiness are functionally intact in psychopaths, although less responsive than those of controls. The neuroimaging literature is unclear as to whether deficits are specific to particular emotions such as fear. The overall pattern of results across studies indicates that people diagnosed with psychopathy demonstrate reduced MRI, fMRI, aMRI, PET, and SPECT activity in areas of the brain.[74] Research has also shown that an approximate 18% smaller amygdala size contributes to a significantly lower emotional sensation in regards to fear, sadness, amongst other negative emotions, which may likely be the reason as to why psychopathic individuals have lower empathy.[75] Some recent fMRI studies have reported that emotion perception deficits in psychopathy are pervasive across emotions (positives and negatives).[76][77][78][79][80] Studies on children with psychopathic tendencies have also shown such associations.[80][81][82][83][84][85] Meta-analyses have also found evidence of impairments in both vocal and facial emotional recognition for several emotions (i.e., not only fear and sadness) in both adults and children/adolescents.[86]

Moral judgment

Psychopathy has been associated with amorality—an absence of, indifference towards, or disregard for moral beliefs. There are few firm data on patterns of moral judgment. Studies of developmental level (sophistication) of moral reasoning found all possible results—lower, higher or the same as non-psychopaths. Studies that compared judgments of personal moral transgressions versus judgments of breaking conventional rules or laws found that psychopaths rated them as equally severe, whereas non-psychopaths rated the rule-breaking as less severe.[87]

A study comparing judgments of whether personal or impersonal harm would be endorsed in order to achieve the rationally maximum (utilitarian) amount of welfare found no significant differences between subjects high and low in psychopathy. However, a further study using the same tests found that prisoners scoring high on the PCL were more likely to endorse impersonal harm or rule violations than non-psychopathic controls were. The psychopathic offenders who scored low in anxiety were also more willing to endorse personal harm on average.[87]

Assessing accidents, where one person harmed another unintentionally, psychopaths judged such actions to be more morally permissible. This result has been considered a reflection of psychopaths' failure to appreciate the emotional aspect of the victim's harmful experience.[88]

Cause

Behavioral genetic studies have identified potential genetic and non-genetic contributors to psychopathy, including influences on brain function. Proponents of the triarchic model believe that psychopathy results from the interaction of genetic predispositions and an adverse environment. What is adverse may differ depending on the underlying predisposition: for example, it is hypothesized that persons having high boldness may respond poorly to punishment but may respond better to rewards and secure attachments.[1][4]

Genetic

Genetically informed studies of the personality characteristics typical of individuals with psychopathy have found moderate genetic (as well as non-genetic) influences. On the PPI, fearless dominance and impulsive antisociality were similarly influenced by genetic factors and uncorrelated with each other. Genetic factors may generally influence the development of psychopathy while environmental factors affect the specific expression of the traits that predominate. A study on a large group of children found more than 60% heritability for "callous-unemotional traits" and that conduct problems among children with these traits had a higher heritability than among children without these traits.[4][72][89]

Environment

A study by Farrington of a sample of London males followed between age 8 and 48 included studying which factors scored 10 or more on the PCL:SV at age 48. The strongest factors included having a convicted parent, being physically neglected, low involvement of the father with the boy, low family income, and coming from a disrupted family. Other significant factors included poor supervision, harsh discipline, large family size, delinquent sibling, young mother, depressed mother, low social class, and poor housing.[90] There has also been association between psychopathy and detrimental treatment by peers.[91] However, it is difficult to determine the extent of an environmental influence on the development of psychopathy because of evidence of its strong heritability.[92]

Brain injury

Researchers have linked head injuries with psychopathy and violence. Since the 1980s, scientists have associated traumatic brain injury, such as damage to the prefrontal cortex, including the orbitofrontal cortex, with psychopathic behavior and a deficient ability to make morally and socially acceptable decisions, a condition that has been termed "acquired sociopathy", or "pseudopsychopathy".[77] Individuals with damage to the area of the prefrontal cortex known as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex show remarkable similarities to diagnosed psychopathic individuals, displaying reduced autonomic response to emotional stimuli, deficits in aversive conditioning, similar preferences in moral and economic decision making, and diminished empathy and social emotions like guilt or shame.[93] These emotional and moral impairments may be especially severe when the brain injury occurs at a young age. Children with early damage in the prefrontal cortex may never fully develop social or moral reasoning and become "psychopathic individuals ... characterized by high levels of aggression and antisocial behavior performed without guilt or empathy for their victims". Additionally, damage to the amygdala may impair the ability of the prefrontal cortex to interpret feedback from the limbic system, which could result in uninhibited signals that manifest in violent and aggressive behavior.[67][68][69][79]

Other theories

Evolutionary explanations

Psychopathy is associated with several adverse life outcomes as well as increased risk of disability and death due to factors such as violence, accidents, homicides, and suicides. This, in combination with the evidence for genetic influences, is evolutionarily puzzling and may suggest that there are compensating evolutionary advantages, and researchers within evolutionary psychology have proposed several evolutionary explanations. According to one hypothesis, some traits associated with psychopathy may be socially adaptive, and psychopathy may be a frequency-dependent, socially parasitic strategy, which may work as long as there is a large population of altruistic and trusting individuals, relative to the population of psychopathic individuals, to be exploited.[89][94] It is also suggested that some traits associated with psychopathy such as early, promiscuous, adulterous, and coercive sexuality may increase reproductive success.[89][94] Robert Hare has stated that many psychopathic males have a pattern of mating with and quickly abandoning women, and thereby have a high fertility rate, resulting in children that may inherit a predisposition to psychopathy.[4][91][95]

Criticism includes that it may be better to look at the contributing personality factors rather than treat psychopathy as a unitary concept due to poor testability. Furthermore, if psychopathy is caused by the combined effects of a very large number of adverse mutations then each mutation may have such a small effect that it escapes natural selection.[4][89] The personality is thought to be influenced by a very large number of genes and may be disrupted by random mutations, and psychopathy may instead be a product of a high mutation load.[89] Psychopathy has alternatively been suggested to be a spandrel, a byproduct, or side-effect, of the evolution of adaptive traits rather than an adaptation in itself.[94][96]

Mechanisms

Psychological

Some laboratory research demonstrates correlations between psychopathy and atypical responses to aversive stimuli, including weak conditioning to painful stimuli and poor learning of avoiding responses that cause punishment, as well as low reactivity in the autonomic nervous system as measured with skin conductance while waiting for a painful stimulus but not when the stimulus occurs. While it has been argued that the reward system functions normally, some studies have also found reduced reactivity to pleasurable stimuli. According to the response modulation hypothesis, psychopathic individuals have also had difficulty switching from an ongoing action despite environmental cues signaling a need to do so.[97] This may explain the difficulty responding to punishment, although it is unclear if it can explain findings such as deficient conditioning. There may be methodological issues regarding the research.[4] While establishing a range of idiosyncrasies on average in linguistic and affective processing under certain conditions, this research program has not confirmed a common pathology of psychopathy.[98]

Neurological

Thanks to advancing MRI studies, experts are able to visualize specific brain differences and abnormalities of individuals with psychopathy in areas that control emotions, social interactions, ethics, morality, regret, impulsivity and conscience within the brain. Blair, a researcher who pioneered research into psychopathic tendencies stated, “With regard to psychopathy, we have clear indications regarding why the pathology gives rise to the emotional and behavioral disturbance and important insights into the neural systems implicated in this pathology”.[79] Dadds et al., remarks that despite a rapidly advancing neuroscience of empathy, little is known about the developmental underpinnings of the psychopathic disconnect between affective and cognitive empathy.[99]

A 2008 review by Weber et al. suggested that psychopathy is sometimes associated with brain abnormalities in prefrontal-temporo-limbic regions that are involved in emotional and learning processes, among others.[100] Neuroimaging studies have found structural and functional differences between those scoring high and low on the PCL-R in a 2011 review by Skeem et al. stating that they are "most notably in the amygdala, hippocampus and parahippocampal gyri, anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, striatum, insula, and frontal and temporal cortex".[4] A 2010 meta-analysis found that antisocial, violent and psychopathic individuals had reduced structure function in the right orbitofrontal cortex, right anterior cingulate cortex and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.[101]

The amygdala and frontal areas have been suggested as particularly important.[70] People scoring 25 or higher in the PCL-R, with an associated history of violent behavior, appear on average to have significantly reduced microstructural integrity between the white matter connecting the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex (such as the uncinate fasciculus). The evidence suggested that the degree of abnormality was significantly related to the degree of psychopathy and may explain the offending behaviors.[71] Furthermore, changes in the amygdala have been associated with "callous-unemotional" traits in children. However, the amygdala has also been associated with positive emotions, and there have been inconsistent results in the studies in particular areas, which may be due to methodological issues.[4]

Some of these findings are consistent with other research and theories. For example, in a neuroimaging study of how individuals with psychopathy respond to emotional words, widespread differences in activation patterns have been shown across the temporal lobe when psychopathic criminals were compared to "normal" volunteers, which is consistent with views in clinical psychology. Additionally, the notion of psychopathy being characterized by low fear is consistent with findings of abnormalities in the amygdala, since deficits in aversive conditioning and instrumental learning are thought to result from amygdala dysfunction, potentially compounded by orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction, although the specific reasons are unknown.[79][102]

Proponents of the primary-secondary psychopathy distinction and triarchic model argue that there are neurological differences between these subgroups of psychopathy which support their views.[103] For instance, the boldness factor in the triarchic model is argued to be associated with reduced activity in the amygdala during fearful or aversive stimuli and reduced startle response, while the disinhibition factor is argued to be associated with impairment of frontal lobe tasks. There is evidence that boldness and disinhibition are genetically distinguishable.[4]

Biochemical

High levels of testosterone combined with low levels of cortisol and/or serotonin have been theorized as contributing factors. Testosterone is "associated with approach-related behavior, reward sensitivity, and fear reduction", and injecting testosterone "shift[s] the balance from punishment to reward sensitivity", decreases fearfulness, and increases "responding to angry faces". Some studies have found that high testosterone levels are associated with antisocial and aggressive behaviors, yet other research suggests that testosterone alone does not cause aggression but increases dominance-seeking. It is unclear from studies if psychopathy correlates with high testosterone levels, but a few studies have found psychopathy to be linked to low cortisol levels and reactivity. Cortisol increases withdrawal behavior and sensitivity to punishment and aversive conditioning, which are abnormally low in individuals with psychopathy and may underlie their impaired aversion learning and disinhibited behavior. High testosterone levels combined with low serotonin levels are associated with "impulsive and highly negative reactions", and may increase violent aggression when an individual is provoked or becomes frustrated.[104] Several animal studies note the role of serotonergic functioning in impulsive aggression and antisocial behavior.[105][106][107][108]

However, some studies on animal and human subjects have suggested that the emotional-interpersonal traits and predatory aggression of psychopathy, in contrast to impulsive and reactive aggression, is related to increased serotoninergic functioning.[109][110][111][112] A study by Dolan and Anderson on the relationship between setotonin and psychopathic traits in a sample of personality disordered offenders, found that serotonin functioning as measured by prolactin response, while inversely associated with impulsive and antisocial traits, were positively correlated with arrogant and deceitful traits, and, to a lesser extent, callous and remorseless traits.[113] Bariş Yildirim theorizes that the 5-HTTLPR "long" allele, which is generally regarded as protective against internalizing disorders, may interact with other serotoninergic genes to create a hyper-regulation and dampening of affective processes that results in psychopathy's emotional impairments.[114] Furthermore, the combination of the 5-HTTLPR long allele and high testosterone levels has been found to result in a reduced response to threat as measured by cortisol reactivity, which mirrors the fear deficits found in those afflicted with psychopathy.[115]

Studies have suggested other correlations. Psychopathy was associated in two studies with an increased ratio of HVA (a dopamine metabolite) to 5-HIAA (a serotonin metabolite).[104] Studies have found that individuals with the traits meeting criteria for psychopathy show a greater dopamine response to potential "rewards" such as monetary promises or taking drugs such as amphetamines. This has been theoretically linked to increased impulsivity.[116] A 2010 British study found that a large 2D:4D digit ratio, an indication of high prenatal estrogen exposure, was a "positive correlate of psychopathy in females, and a positive correlate of callous affect (psychopathy sub-scale) in males".[117]

Findings have also shown monoamine oxidase A to affect the predictive ability of the PCL-R.[118] Monoamine oxidases (MAOs) are enzymes that are involved in the breakdown of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine and are, therefore, capable of influencing feelings, mood, and behavior in individuals.[119] Findings suggest that further research is needed in this area.[120][121]

Diagnosis

Tools

Psychopathy Checklist

Psychopathy is most commonly assessed with the Psychopathy Checklist, Revised (PCL-R), created by Robert D. Hare based on Cleckley's criteria from the 1940s, criminological concepts such as those of William and Joan McCord, and his own research on criminals and incarcerated offenders in Canada.[72][122][123] The PCL-R is widely used and is referred to by some as the "gold standard" for assessing psychopathy.[124] There are nonetheless numerous criticisms of the PCL-R as a theoretical tool and in real-world usage.[125][126][127][128][129]

Psychopathic Personality Inventory

Unlike the PCL, the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) was developed to comprehensively index personality traits without explicitly referring to antisocial or criminal behaviors themselves. It is a self-report scale that was developed originally for non-clinical samples (e.g. university students) rather than prisoners, though may be used with the latter. It was revised in 2005 to become the PPI-R and now comprises 154 items organized into eight subscales.[130] The item scores have been found to group into two overarching and largely separate factors (unlike the PCL-R factors), Fearless-Dominance and Impulsive Antisociality, plus a third factor, Coldheartedness, which is largely dependent on scores on the other two.[4] Factor 1 is associated with social efficacy while Factor 2 is associated with maladaptive tendencies. A person may score at different levels on the different factors, but the overall score indicates the extent of psychopathic personality.[4]

DSM and ICD

There are currently two widely established systems for classifying mental disorders—the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) produced by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) produced by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Both list categories of disorders thought to be distinct types, and have deliberately converged their codes in recent revisions so that the manuals are often broadly comparable, although significant differences remain.

The first edition of the DSM in 1952 had a section on sociopathic personality disturbances, then a general term that included such things as homosexuality and alcoholism as well as an "antisocial reaction" and "dyssocial reaction". The latter two eventually became antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) in the DSM and dissocial personality disorder in the ICD. Both manuals have stated that their diagnoses have been referred to, or include what is referred to, as psychopathy or sociopathy, although neither diagnostic manual has ever included a disorder officially titled as such.[4][7][10]

Other tools

There are some traditional personality tests that contain subscales relating to psychopathy, though they assess relatively non-specific tendencies towards antisocial or criminal behavior. These include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Psychopathic Deviate scale), California Psychological Inventory (Socialization scale), and Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory Antisocial Personality Disorder scale. There is also the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP) and the Hare Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (HSRP), but in terms of self-report tests, the PPI/PPI-R has become more used than either of these in modern psychopathy research on adults.[4]

Comorbidity

As with other mental disorders, psychopathy as a personality disorder may be present with a variety of other diagnosable conditions. Studies especially suggest strong comorbidity with antisocial personality disorder. Among numerous studies, positive correlations have also been reported between psychopathy and histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, paranoid, and schizoid personality disorders, panic and obsessive–compulsive disorders, but not neurotic disorders in general, schizophrenia, or depression.[35][131][132][133][134]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is known to be highly comorbid with conduct disorder (a theorized precursor to ASPD), and may also co-occur with psychopathic tendencies. This may be explained in part by deficits in executive function.[131] Anxiety disorders often co-occur with ASPD, and contrary to assumptions, psychopathy can sometimes be marked by anxiety; this appears to be related to items from Factor 2 but not Factor 1 of the PCL-R. Psychopathy is also associated with substance use disorders.[37][131][133][135][136]

It has been suggested that psychopathy may be comorbid with several other conditions than these,[136] but limited work on comorbidity has been carried out. This may be partly due to difficulties in using inpatient groups from certain institutions to assess comorbidity, owing to the likelihood of some bias in sample selection.[131]

Further considerations

Sex differences

Research on psychopathy has largely been done on men and the PCL-R was developed using mainly male criminal samples, raising the question of how well the results apply to women. Men score higher than women on both the PCL-R and the PPI and on both of their main scales. The differences tend to be somewhat larger on the interpersonal-affective scale than on the antisocial scale. Most but not all studies have found broadly similar factor structure for men and women.[4]

Many associations with other personality traits are similar, although in one study the antisocial factor was more strongly related with impulsivity in men and more strongly related with openness to experience in women. It has been suggested that psychopathy in men manifest more as an antisocial pattern while in women it manifests more as a histrionic pattern. Studies on this have shown mixed results. PCL-R scores may be somewhat less predictive of violence and recidivism in women. On the other hand, psychopathy may have a stronger relationship with suicide and possibly internalizing symptoms in women. A suggestion is that psychopathy manifests more as externalizing behaviors in men and more as internalizing behaviors in women.[4]

Studies have also found that women in prison score significantly lower on psychopathy than men, with one study reporting only 11 percent of violent females in prison met the psychopathy criteria in comparison to 31 percent of violent males.[137] Other studies have also pointed out that high psychopathic females are rare in forensic settings.[138]

Management

Clinical

Psychopathy has often been considered untreatable. Its unique characteristics makes it among the most refractory of personality disorders, a class of mental illnesses that are already traditionally considered difficult to treat.[139][140] People afflicted with psychopathy are generally unmotivated to seek treatment for their condition, and can be uncooperative in therapy.[124][139] Attempts to treat psychopathy with the current tools available to psychiatry have been disappointing. Harris and Rice's Handbook of Psychopathy says that there is currently little evidence for a cure or effective treatment for psychopathy; as yet, no pharmacological therapies are known to or have been trialed for alleviating the emotional, interpersonal and moral deficits of psychopathy, and patients with psychopathy who undergo psychotherapy might gain the skills to become more adept at the manipulation and deception of others and be more likely to commit crime.[141] Some studies suggest that punishment and behavior modification techniques are ineffective at modifying the behavior of psychopathic individuals as they are insensitive to punishment or threat.[141][142] These failures have led to a widely pessimistic view on its treatment prospects, a view that is exacerbated by the little research being done into this disorder compared to the efforts committed to other mental illnesses, which makes it more difficult to gain the understanding of this condition that is necessary to develop effective therapies.[143][144]

Although the core character deficits of highly psychopathic individuals are likely to be highly incorrigible to the currently available treatment methods, the antisocial and criminal behavior associated with it may be more amenable to management, the management of which being the main aim of therapy programs in correctional settings.[139] It has been suggested that the treatments that may be most likely to be effective at reducing overt antisocial and criminal behavior are those that focus on self-interest, emphasizing the tangible, material value of prosocial behavior, with interventions that develop skills to obtain what the patient wants out of life in prosocial rather than antisocial ways.[145][146] To this end, various therapies have been tried with the aim of reducing the criminal activity of incarcerated offenders with psychopathy, with mixed success.[139] As psychopathic individuals are insensitive to sanction, reward-based management, in which small privileges are granted in exchange for good behavior, has been suggested and used to manage their behavior in institutional settings.[147]

Psychiatric medications may also alleviate co-occurring conditions sometimes associated with the disorder or with symptoms such as aggression or impulsivity, including antipsychotic, antidepressant or mood-stabilizing medications, although none have yet been approved by the FDA for this purpose.[4][7][10][148][149] For example, a study found that the antipsychotic clozapine may be effective in reducing various behavioral dysfunctions in a sample of high-security hospital inpatients with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathic traits.[150] However, research into the pharmacological treatment of psychopathy and the related condition antisocial personality disorder is minimal, with much of the knowledge in this area being extrapolations based on what is known about pharmacology in other mental disorders.[139][151]

Legal

The PCL-R, the PCL:SV, and the PCL:YV are highly regarded and widely used in criminal justice settings, particularly in North America. They may be used for risk assessment and for assessing treatment potential and be used as part of the decisions regarding bail, sentence, which prison to use, parole, and regarding whether a youth should be tried as a juvenile or as an adult. There have been several criticisms against its use in legal settings. They include the general criticisms against the PCL-R, the availability of other risk assessment tools which may have advantages, and the excessive pessimism surrounding the prognosis and treatment possibilities of those who are diagnosed with psychopathy.[4]

The interrater reliability of the PCL-R can be high when used carefully in research but tend to be poor in applied settings. In particular Factor 1 items are somewhat subjective. In sexually violent predator cases the PCL-R scores given by prosecution experts were consistently higher than those given by defense experts in one study. The scoring may also be influenced by other differences between raters. In one study it was estimated that of the PCL-R variance, about 45% was due to true offender differences, 20% was due to which side the rater testified for, and 30% was due to other rater differences.[4]

To aid a criminal investigation, certain interrogation approaches may be used to exploit and leverage the personality traits of suspects thought to have psychopathy and make them more likely to divulge information.[152]

United Kingdom

The PCL-R score cut-off for a label of psychopathy is 25 out of 40 in the United Kingdom, instead of 30 as it is in the United States.[4][6]

In the United Kingdom, "psychopathic disorder" was legally defined in the Mental Health Act (UK), under MHA1983,[6][153] as "a persistent disorder or disability of mind (whether or not including significant impairment of intelligence) which results in abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person concerned". This term was intended to reflect the presence of a personality disorder in terms of conditions for detention under the Mental Health Act 1983. Amendments to MHA1983 within the Mental Health Act 2007 abolished the term "psychopathic disorder", with all conditions for detention (e.g. mental illness, personality disorder, etc.) encompassed by the generic term of "mental disorder".[154]

In England and Wales, the diagnosis of dissocial personality disorder is grounds for detention in secure psychiatric hospitals under the Mental Health Act if they have committed serious crimes, but since such individuals are disruptive to other patients and not responsive to usual treatment methods this alternative to traditional incarceration is often not used.[155]

United States

"Sexual psychopath" laws

Starting in the 1930s, before some modern concepts of psychopathy were developed, "sexual psychopath" laws, the term referring broadly to mental illness, were introduced by some states, and by the mid-1960s more than half of the states had such laws. Sexual offenses were considered to be caused by underlying mental illnesses, and it was thought that sex offenders should be treated, in agreement with the general rehabilitative trends at this time. Courts committed sex offenders to a mental health facility for community protection and treatment.[156][157][158]

Starting in 1970, many of these laws were modified or abolished in favor of more traditional responses such as imprisonment due to criticism of the "sexual psychopath" concept as lacking scientific evidence, the treatment being ineffective, and predictions of future offending being dubious. There were also a series of cases where persons treated and released committed new sexual offenses. Starting in the 1990s, several states have passed sexually dangerous person laws, including registration, housing restrictions, public notification, mandatory reporting by health care professionals, and civil commitment, which permits indefinite confinement after a sentence has been completed.[158] Psychopathy measurements may be used in the confinement decision process.[4]

Prognosis

The prognosis for psychopathy in forensic and clinical settings is quite poor, with some studies reporting that treatment may worsen the antisocial aspects of psychopathy as measured by recidivism rates, though it is noted that one of the frequently cited studies finding increased criminal recidivism after treatment, a 2011 retrospective study of a treatment program in the 1960s, had several serious methodological problems and likely would not be approved of today.[4][124] However, some relatively rigorous quasi-experimental studies using more modern treatment methods have found improvements regarding reducing future violent and other criminal behavior, regardless of PCL-R scores, although none were randomized controlled trials. Various other studies have found improvements in risk factors for crime such as substance abuse. No study has yet examined whether the personality traits that form the core character disturbances of psychopathy could be changed by such treatments.[4][159]

Frequency

A 2008 study using the PCL:SV found that 1.2% of a US sample scored 13 or more out of 24, indicating "potential psychopathy". The scores correlated significantly with violence, alcohol use, and lower intelligence.[37] A 2009 British study by Coid et al., also using the PCL:SV, reported a community prevalence of 0.6% scoring 13 or more. However, if the scoring was adjusted to the recommended 18 or more,[160] this would have left the prevalence closer to 0.1%.[161] The scores correlated with younger age, male gender, suicide attempts, violence, imprisonment, homelessness, drug dependence, personality disorders (histrionic, borderline and antisocial), and panic and obsessive–compulsive disorders.[162]

Psychopathy has a much higher prevalence in the convicted and incarcerated population, where it is thought that an estimated 15–25% of prisoners qualify for the diagnosis.[163] A study on a sample of inmates in the UK found that 7.7% of the inmates interviewed met the PCL-R cut-off of 30 for a diagnosis of psychopathy.[35] A study on a sample of inmates in Iran using the PCL:SV found a prevalence of 23% scoring 18 or more.[164] A study by Nathan Brooks from Bond University found that around one in five corporate bosses display clinically significant psychopathic traits - a proportion similar to that among prisoners.[165]

Society and culture

In the workplace

There is limited research on psychopathy in the general work populace, in part because the PCL-R includes antisocial behavior as a significant core factor (obtaining a PCL-R score above the threshold is unlikely without having significant scores on the antisocial-lifestyle factor) and does not include positive adjustment characteristics, and most researchers have studied psychopathy in incarcerated criminals, a relatively accessible population of research subjects.[166]

However, psychologists Fritzon and Board, in their study comparing the incidence of personality disorders in business executives against criminals detained in a mental hospital, found that the profiles of some senior business managers contained significant elements of personality disorders, including those referred to as the "emotional components", or interpersonal-affective traits, of psychopathy. Factors such as boldness, disinhibition, and meanness as defined in the triarchic model, in combination with other advantages such as a favorable upbringing and high intelligence, are thought to correlate with stress immunity and stability, and may contribute to this particular expression.[166] Such individuals are sometimes referred to as "successful psychopaths" or "corporate psychopaths" and they may not always have extensive histories of traditional criminal or antisocial behavior characteristic of the traditional conceptualization of psychopathy.[56] Robert Hare claims that the prevalence of psychopathic traits is higher in the business world than in the general population, reporting that while about 1% of the general population meet the clinical criteria for psychopathy, figures of around 3–4% have been cited for more senior positions in business.[4][167][168] Hare considers newspaper tycoon Robert Maxwell to have been a strong candidate as a "corporate psychopath".[169]

Academics on this subject believe that although psychopathy is manifested in only a small percentage of workplace staff, it is more common at higher levels of corporate organizations, and its negative effects (for example, increased bullying, conflict, stress, staff turnover, absenteeism, reduction in productivity) often causes a ripple effect throughout an organization, setting the tone for an entire corporate culture. Employees with the disorder are self-serving opportunists, and may disadvantage their own organizations to further their own interests.[170] They may be charming to staff above their level in the workplace hierarchy, aiding their ascent through the organization, but abusive to staff below their level, and can do enormous damage when they are positioned in senior management roles.[171][172] Psychopathy as measured by the PCL-R is associated with lower performance appraisals among corporate professionals.[173] The psychologist Oliver James identifies psychopathy as one of the dark triadic traits in the workplace, the others being narcissism and Machiavellianism, which, like psychopathy, can have negative consequences.[174]

According to a study from the University of Notre Dame published in the Journal of Business Ethics, psychopaths have a natural advantage in workplaces overrun by abusive supervision, and are more likely to thrive under abusive bosses, being more resistant to stress, including interpersonal abuse, and having less of a need for positive relationships than others.[175][176][177]

In fiction

Characters with psychopathy or sociopathy are some of the most notorious characters in film and literature, but their characterizations may only vaguely or partly relate to the concept of psychopathy as it is defined in psychiatry, criminology, and research. The character may be identified as having psychopathy within the fictional work itself, by its creators, or from the opinions of audiences and critics, and may be based on undefined popular stereotypes of psychopathy.[178] Characters with psychopathic traits have appeared in Greek and Roman mythology, Bible stories, and some of Shakespeare's works.[179]

Such characters are often portrayed in an exaggerated fashion and typically in the role of a villain or antihero, where the general characteristics and stereotypes associated with psychopathy are useful to facilitate conflict and danger. Because the definitions, criteria, and popular conceptions throughout its history have varied over the years and continue to change even now, many of the characters characterized as psychopathic in notable works at the time of publication may no longer fit the current definition and conception of psychopathy. There are several archetypal images of psychopathy in both lay and professional accounts which only partly overlap and can involve contradictory traits: the charming con artist, the deranged serial killer and mass murderer, the callous and scheming businessperson, and the chronic low-level offender and juvenile delinquent. The public concept reflects some combination of fear of a mythical bogeyman, the disgust and intrigue surrounding evil, and fascination and sometimes perhaps envy of people who might appear to go through life without attachments and unencumbered by guilt, anguish or insecurity.[4]

History

Etymology

The word psychopathy is a joining of the Greek words psyche (ψυχή) "soul" and pathos (πάθος) "suffering, feeling".[180] The first documented use is from 1847 in Germany as psychopatisch,[181] and the noun psychopath has been traced to 1885.[182] In medicine, patho- has a more specific meaning of disease (thus pathology has meant the study of disease since 1610, and psychopathology has meant the study of mental disorder in general since 1847. A sense of "a subject of pathology, morbid, excessive" is attested from 1845,[183] including the phrase pathological liar from 1891 in the medical literature).

The term psychopathy initially had a very general meaning referring to all sorts of mental disorders and social aberrations, popularised from 1891 in Germany by Koch's concept of "psychopathic inferiority" (psychopathische Minderwertigkeiten). Some medical dictionaries still define psychopathy in both a narrow and broad sense, such as MedlinePlus from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.[184] On the other hand, Stedman's Medical Dictionary defines psychopathy only as an outdated term for an antisocial type of personality disorder.[185]

The term psychosis was also used in Germany from 1841, originally in a very general sense. The suffix -ωσις (-osis) meant in this case "abnormal condition". This term or its adjective psychotic would come to refer to the more severe mental disturbances and then specifically to mental states or disorders characterized by hallucinations, delusions or in some other sense markedly out of touch with reality.[186]

The slang term psycho has been traced to a shortening of the adjective psychopathic from 1936, and from 1942 as a shortening of the noun psychopath,[187] but it is also used as shorthand for psychotic or crazed.[188]

The media usually uses the term psychopath to designate any criminal whose offenses are particularly abhorrent and unnatural, but that is not its original or general psychiatric meaning.[189]

Sociopathy

The word element socio- has been commonly used in compound words since around 1880.[190][191] The term sociopathy may have been first introduced in 1909 in Germany by biological psychiatrist Karl Birnbaum and in 1930 in the US by educational psychologist George E. Partridge, as an alternative to the concept of psychopathy.[190] It was used to indicate that the defining feature is violation of social norms, or antisocial behavior, and may be social or biological in origin.[192][193][194][195]

The term is used in various different ways in contemporary usage. Robert Hare stated in the popular science book Snakes in Suits that sociopathy and psychopathy are often used interchangeably, but in some cases the term sociopathy is preferred because it is less likely than is psychopathy to be confused with psychosis, whereas in other cases the two terms may be used with different meanings that reflect the user's views on the origins and determinants of the disorder. Hare contended that the term sociopathy is preferred by those that see the causes as due to social factors and early environment, and the term psychopathy preferred by those who believe that there are psychological, biological, and genetic factors involved in addition to environmental factors.[91] Hare also provides his own definitions: he describes psychopathy as not having a sense of empathy or morality, but sociopathy as only differing from the average person in the sense of right and wrong.[196][197]

Precursors

Ancient writings that have been connected to psychopathic traits include Deuteronomy 21:18–21, which was written around 700 BCE, and a description of an unscrupulous man by the Greek philosopher Theophrastus around 300 BCE.[179]

The concept of psychopathy has been indirectly connected to the early 19th century with the work of Pinel (1801; "mania without delirium") and Pritchard (1835; "moral insanity"), although historians have largely discredited the idea of a direct equivalence.[198] Psychopathy originally described any illness of the mind, but found its application to a narrow subset of mental conditions when was used toward the end of the 19th century by the German psychiatrist Julius Koch (1891) to describe various behavioral and moral dysfunction in the absence of an obvious mental illness or intellectual disability. He applied the term psychopathic inferiority (psychopathischen Minderwertigkeiten) to various chronic conditions and character disorders, and his work would influence the later conception of the personality disorder.[4][199]

The term psychopathic came to be used to describe a diverse range of dysfunctional or antisocial behavior and mental and sexual deviances, including at the time homosexuality. It was often used to imply an underlying "constitutional" or genetic origin. Disparate early descriptions likely set the stage for modern controversies about the definition of psychopathy.[4]

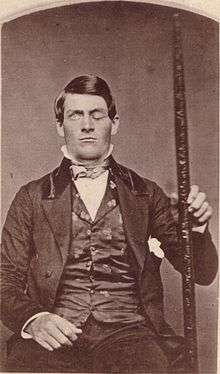

20th century

An influential figure in shaping modern American conceptualizations of psychopathy was American psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley. In his classic monograph, The Mask of Sanity (1941), Cleckley drew on a small series of vivid case studies of psychiatric patients at a Veterans Administration hospital in Georgia to describe the disorder. Cleckley used the metaphor of the "mask" to refer to the tendency of psychopaths to appear confident, personable, and well-adjusted compared to most psychiatric patients, while revealing underlying pathology through their actions over time. Cleckley formulated sixteen criteria to describe the disorder.[4] The Scottish psychiatrist David Henderson had also been influential in Europe from 1939 in narrowing the diagnosis.[200]

The diagnostic category of sociopathic personality in early editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)[201] had some key similarities to Cleckley's ideas, though in 1980 when renamed Antisocial Personality Disorder some of the underlying personality assumptions were removed.[7] In 1980, Canadian psychologist Robert D. Hare introduced an alternative measure, the "Psychopathy Checklist" (PCL) based largely on Cleckley's criteria, which was revised in 1991 (PCL-R),[163][202] and is the most widely used measure of psychopathy.[203] There are also several self-report tests, with the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) used more often among these in contemporary adult research.[4]

Famous individuals have sometimes been diagnosed, albeit at a distance, as psychopaths. As one example out of many possible from history, in a 1972 version of a secret report originally prepared for the Office of Strategic Services in 1943, and which may have been intended to be used as propaganda,[204][205] non-medical psychoanalyst Walter C. Langer suggested Adolf Hitler was probably a psychopath.[206] However, others have not drawn this conclusion; clinical forensic psychologist Glenn Walters argues that Hitler's actions do not warrant a diagnosis of psychopathy as, although he showed several characteristics of criminality, he was not always egocentric, callously disregarding of feelings or lacking impulse control, and there is no proof he could not learn from mistakes.[207]

See also

References

- Patrick, Christopher; Fowles, Don; Krueger, Robert (August 2009). "Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness". Development and Psychopathology. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 21 (3): 913–938. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000492. PMID 19583890.

- Hare, Robert D. (1999). Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. New York City: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1572304512.

- Stone, Michael H.; Brucato, Gary (2019). The New Evil: Understanding the Emergence of Modern Violent Crime. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 48–52. ISBN 978-1633885325.

- Skeem, Jennifer L.; Polaschek, Devon L.L.; Patrick, Christopher J.; Lilienfeld, Scott O. (December 15, 2011). "Psychopathic Personality: Bridging the Gap Between Scientific Evidence and Public Policy". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. 12 (3): 95–162. doi:10.1177/1529100611426706. PMID 26167886. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016.

- Partridge, George E. (July 1930). "Current Conceptions of Psychopathic Personality". The American Journal of Psychiatry. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Psychiatric Association. 1 (87): 53–99. doi:10.1176/ajp.87.1.53.

- Semple, David (2005). The Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 448–9. ISBN 978-0-19-852783-1.

- Patrick, Christopher (2005). Handbook of Psychopathy. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-60623-804-2.

- Hare, Robert D. (February 1, 1996). "Psychopathy and Antisocial Personality Disorder: A Case of Diagnostic Confusion". Psychiatric Times. New York City: MJH Associates. 13 (2). Archived from the original on May 28, 2013.

- Hare, Robert D.; Hart, Stephen D.; Harpur, Timothy J. (1991). "Psychopathy and the DSM-IV criteria for antisocial personality disorder". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 100 (3): 391–8. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.391. PMID 1918618.

- Andrade, Joel (23 Mar 2009). Handbook of Violence Risk Assessment and Treatment: New Approaches for Mental Health Professionals. New York City: Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8261-9904-1. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Hare Psychopathy Checklist". Encyclopedia of Mental Disorders. Archived from the original on September 4, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- Delisi, Matt; Vaughn, Michael G.; Beaver, Kevin M.; Wright, John Paul (2009). "The Hannibal Lecter Myth: Psychopathy and Verbal Intelligence in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study". Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. New York City: Springer Science+Business Media. 32 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1007/s10862-009-9147-z.

- Hare, Robert D. (1999). Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. New York City: Guilford Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-57230-451-2.

- Harris, Grant T.; Rice, Marnie E.; Quinsey, Vernon L. (1994). "Psychopathy as a taxon: Evidence that psychopaths are a discrete class". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 62 (2): 387–97. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.62.2.387. PMID 8201078.

- Marcus, David K.; John, Siji L.; Edens, John F. (2004). "A Taxometric Analysis of Psychopathic Personality". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. 113 (4): 626–35. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.626. PMID 15535794.

- Edens, John F.; Marcus, David K. (2006). "Psychopathic, Not Psychopath: Taxometric Evidence for the Dimensional Structure of Psychopathy". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. 115 (1): 131–44. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.131. PMID 16492104.

- Edens, John F.; Marcus, David K.; Lilienfeld, Scott O.; Poythress, Norman G., Jr. (2006). "Psychopathic, Not Psychopath: Taxometric Evidence for the Dimensional Structure of Psychopathy" (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. 115 (1): 131–44. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.131. PMID 16492104.

- Derefinko, Karen J. (December 2015). "Psychopathy and Low Anxiety: Meta-Analytic Evidence for the Absence of Inhibition, Not Affect". Journal of Personality. New York City: Wiley. 83 (6): 693–709. doi:10.1111/jopy.12124. PMID 25130868.

- Widiger, Thomas A.; Lynam, Donald R. (2002). "Psychopathy and the Five-Factor Model of Personality". In Millon, Theodore; Simonsen, Erik; Birket-Smith, Morten; et al. (eds.). Psychopathy: Antisocial, Criminal, and Violent Behavior. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 171–87. ISBN 978-1-57230-864-0.

- Zuckerman, Marvin (1991). Psychobiology of personality. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-521-35942-9.

- Otto F., Kernberg (2004). Aggressivity, Narcissism, and Self-Destructiveness in the Psychotherapeutic Relationship: New Developments in the Psychopathology and Psychotherapy of Severe Personality Disorders. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 130–153. ISBN 978-0-300-10180-5.

- Paulhus, Delroy L.; Williams, Kevin M. (December 2002). "The Dark Triad of Personality". Journal of Research in Personality. New York City: Elsevier. 36 (6): 556–563. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6.

- Regoli, Robert M.; Hewitt, John D.; DeLisi, Matt (2011). Delinquency in Society: The Essentials. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7637-7790-6.

- Campbell, W. Keith; Miller, Joshua D. (2011). The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments. New York City: Wiley. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-118-02924-4.

- Leary, Mark R.; Hoyle, Rick H. (2009). Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. New York City: Guilford Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-59385-647-2.

- Jones, Daniel N.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (2010). "Differentiating the Dark Triad within the interpersonal circumplex". In Horowitz, Leonard M.; Strack, Stephen (eds.). Handbook of interpersonal theory and research. New York City: Guilford Press. pp. 249–67. ISBN 978-1118001868.

- Chabrol H.; Van Leeuwen N.; Rodgers R.; Sejourne N. (2009). "Contributions of psychopathic, narcissistic, Machiavellian, and sadistic personality traits to juvenile delinquency". Personality and Individual Differences. 47 (7): 734–739. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.020.

- Buckels, E. E.; Jones, D. N.; Paulhus, D. L. (2013). "Behavioral confirmation of everyday sadism". Psychological Science. 24 (11): 2201–9. doi:10.1177/0956797613490749. PMID 24022650.

- Benjamin, Sadock; Virginia, Sadock; Pedro, Ruiz (2017). Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry (2 Volume Set) (10th ed.). ISBN 978-1451100471.

- Lewis, Dorothy; Yeager, Catherine; Blake, Pamela; Bard, Barbara; Strenziok, Maren (2004). "Ethics Questions Raised by the Neuropsychiatric, Neuropsychological, Educational, Developmental, and Family Characteristics of 18 Juveniles Awaiting Execution in Texas". J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 32: 408–429. PMID 15704627.

- Walters, GD (April 2004). "The trouble with psychopathy as a general theory of crime". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 48 (2): 133–48. doi:10.1177/0306624X03259472. PMID 15070462.

- Martens, WH (June 2008). "The problem with Robert Hare's psychopathy checklist: incorrect conclusions, high risk of misuse, and lack of reliability". Medicine and Law. 27 (2): 449–62. PMID 18693491.

- de Almeida, Rosa Maria Martins; Cabral, João Carlos Centurion; Narvaes, Rodrigo (2015). "Behavioural, hormonal and neurobiological mechanisms of aggressive behaviour in human and nonhuman primates". Physiology & Behavior. 143: 121–135. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.02.053. PMID 25749197.

- Patrick, Christopher J, ed. (2005). Handbook of Psychopathy. New York City: Guilford Press. pp. 440–3. ISBN 978-1593855918.