Demonic possession

Demonic possession involves the belief that an alien spirit, demon, or entity controls a person's actions.[1] Those who believe themselves so possessed commonly claim that symptoms of demonic possession include missing memories, perceptual distortions, loss of a sense of control, and hyper-suggestibility.[2] Erika Bourguignon found in a study of 488 societies worldwide that seventy-four percent believe in possession by spirits, with the highest numbers of believing societies in Pacific cultures and the lowest incidence among Native Americans of both North and South America.[3]

Abrahamic religions

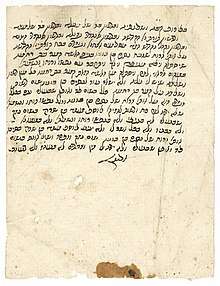

Judaism

While demons exist in the Jewish religion, they are seen as agents of God. In the Hebrew Bible, one of the very few mentions of demons harassing mortals is in the First Book of Samuel,

"Saul’s attendants said to him, “See, an evil spirit from God is tormenting you."[4] There are few mentions in other Judaic religious works, with only one in the Mishnah.[5] Both the Talmud and the Midrash[6] mention demons, but though Kabbalists trace demonology throughout the Jewish holy books, little is mentioned of possession.[5]

In the 16th century, Isaac Luria, a Jewish mystic, wrote about the transmigration of souls seeking perfection. His disciples took his idea a step further, creating the idea of a dybbuk, a soul inhabiting a victim until it had accomplished its task or atoned for its sin.[7] The dybbuk appears in Jewish folklore and literature, as well as in chronicles of Jewish life.[8]

Christianity

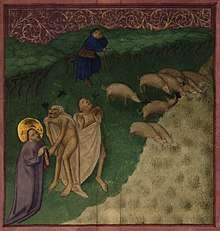

From its beginning,[1] Christianity has held that possession derives from the Devil, i.e. Satan, his lesser demons, the fallen angels.[4] In the battle between Satan and Heaven, one of Satan's strategies is to possess humans.[1] The New Testament mentions several episodes in which Jesus drove out demons from persons.[4]

Catholicism

Catholic exorcists differentiate between "ordinary" Satanic/demonic activity or influence (mundane everyday temptations) and "extraordinary" Satanic/demonic activity, which can take six different forms, ranging from complete control by Satan or some demon(s) to voluntary submission:[9]

- Possession, in which Satan or some demon(s) takes full possession of a person's body without their consent, but it's usually because this person did something that caused it to happen.

- Obsession, which includes sudden attacks of irrationally obsessive thoughts, usually culminating in suicidal ideation, and which typically influences dreams.

- Oppression, in which there is no loss of consciousness or involuntary action, such as in the biblical Book of Job in which Job was tormented by a series of misfortunes in business, material possessions, family, and health.

- External physical pain caused by Satan or some demon(s).

- Infestation, which affects houses, objects/things, or animals; and

- Subjection, in which a person voluntarily submits to Satan or some demon(s).

In the Roman Ritual, true demonic or satanic possession has been characterized since the Middle Ages, by the following four typical characteristics:[10][11]

- Manifestation of superhuman strength.

- Speaking in tongues or languages that the victim cannot know.

- Revelation of knowledge, distant or hidden, that the victim cannot know.

- Blasphemous rage, obscene hand gestures, using profanity and an aversion to holy symbols and names, relics or places.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia states, "Ecclesiastical authorities are reluctant to admit diabolical possession in most cases, because many can be explained by physical or mental illness alone. Therefore, medical and psychological examinations are necessary before the performance of major exorcism. The standard that must be met is that of moral certitude (De exorcismis, 16). For an exorcist to be morally certain, or beyond reasonable doubt, that he is dealing with a genuine case of demonic possession, there must be no other reasonable explanation for the phenomena in question."[12]

The New Testament (of The Holy Bible) indicates that people can be possessed by demons, but that the demons respond and submit to Jesus Christ's authority:

33In the synagogue, there was a man possessed by a demon, an evil spirit. He cried out at the top of his voice,34 "Ha! What do you want with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!"35 "Be quiet!" Jesus said sternly. "Come out of him!" Then the demon threw the man down before them all and came out without injuring him.36 All the people were amazed and said to each other, "What is this teaching? With authority and power he gives orders to evil spirits and they come out!"37 And the news about him spread throughout the surrounding area. (Luke 4:33-35 NIV)[13]

It also indicates that demons can possess animals as in the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac.[13]

Official Catholic doctrine affirms that demonic possession can occur as distinguished from mental illness,[14] but stresses that cases of mental illness should not be misdiagnosed as demonic influence. Catholic exorcisms can occur only under the authority of a bishop and in accordance with strict rules; a simple exorcism also occurs during baptism.[1]

Protestantism

The literal view of demonic possession is held by a number of Christian denominations. In both charismatic and evangelical Christianity, exorcisms of demons are often carried out by individuals or groups known as Deliverance ministries.[15] Symptoms of such possessions, according to these groups, can include chronic fatigue syndrome, homosexuality, addiction to pornography, and alcoholism.[16] The New Testament's description of people who had evil spirits includes a knowledge of future events (Acts 16:16) and great strength (Act 19:13-16),[4] among others, and shows that those with evil spirits can speak of Christ (Mark 3:7-11).[4]

In medieval Great Britain, the Christian church had offered suggestions on safeguarding one's home. Suggestions ranged from dousing a household with holy water, placing wax and herbs on thresholds to "ward off witches occult," and avoiding certain areas of townships known to be frequented by witches and Devil worshippers after dark.[17] Afflicted persons were restricted from entering the church, but might share the shelter of the porch with lepers and persons of offensive life. After the prayers, if quiet, they might come in to receive the bishop's blessing and listen to the sermon. They were daily fed and prayed over by the exorcists, and, in case of recovery, after a fast of from 20 to 40 days, were admitted to the Eucharist, and their names and cures entered in the church records.[18] In 1603, the Church of England forbade its clergy from performing exorcisms because of numerous fraudulent cases of demonic possession.[14]

Islam

Various types of creatures, such as jinn, shayatin, 'afarit and ruh, found within Islamic culture, are often held to be responsible for demonic possession. Usually, Iblis, the leader of evil spirits, only tempts humans into sin by following their lower desires.[19][20] Though not directly attested in the Quran, the notion of jinn possessing humans is widespread among Muslims and also accepted by most Islamic scholars.[21] There are various reasons given as to why a jinn might seek to possess an individual, such as falling in love with them, taking revenge for hurting them or their relatives, or other undefined reasons.[22][23] Since jinn are not necessarily evil, they are distinguished from cultural concepts of possession by devils/demons.[24] In contrast, the shayatin are inherently evil.[25] Hadiths suggest that the demons/devils whisper from within the human body, within or next to the heart, "devilish whisperings" (Arabic: waswās وَسْوَاس) are thought of as a kind of possession.[26]

Buddhism

In Buddhism, a demon can either be a being suffering in the hell realm[27] or it could be a delusion.[28] Before Siddhartha became Gautama Buddha, He was challenged by Mara, the embodiment of temptation, and overcame it.[29] In traditional Buddhism, four metaphorical forms of "māra" are given:[30]

- Kleśa-māra, or Ma̋ra as the embodiment of all unskillful emotions, such as greed, hate and delusion.(the Demons of delusions/defilement and unwholesome states)

- Mṛtyu-māra, or Māra as death. (the Demons of the Lord of death)

- Skandha-māra, or Māra as metaphor for the entirety of conditioned existence.(the Demons of contaminated aggregates)

- Devaputra-māra, the deva of the sensuous realm, who tries to prevent Gautama Buddha from attaining liberation from the cycle of rebirth on the night of the Buddha's enlightenment.(the Demons of sons of deva Gods/desire and temptation)[31]

It is believed that the demon will depart to a different realm once the demon is appeased.[27]

Other religions

In many of the Diasporic traditional African religions, possessing demons are not necessarily harmful or evil, but are rather seeking to rebuke misconduct in the living.[32] As Pentecostal and Charismatic Christian sects move into both African and Oceanic areas, a merger of belief can take place. Demons can be representative of the "old" indigenous religions, which the Christian ministers work to exorcise.[33]

Medicine and psychology

Those who profess a belief in demonic possession, also referred to as possessive trance disorder,[1] have sometimes ascribed to possession the symptoms associated with physical or mental illnesses, such as hysteria, Tourette syndrome, epilepsy,[34] schizophrenia,[35]conversion disorder or dissociative identity disorder.[36] In its article on Dissociative Identity Disorder, the DSM-5 states, "Possession-form identities in dissociative identity disorder typically manifest as behaviors that appear as if a 'spirit,' supernatural being, or outside person has taken control such that the individual begins speaking or acting in a distinctly different manner.[37]" It is not uncommon to ascribe the experience of sleep paralysis to demonic possession, although it's not a physical or mental illness.[38] The symptoms vary across cultures.[39] Demonic possession is not a valid psychiatric or medical diagnosis recognized by either the DSM-5 or the ICD-10.[40] The DSM-5 indicates that personality states of dissociative identity disorder may be interpreted as possession in some cultures, and instances of spirit possession are often related to traumatic experiences—suggesting that possession experiences may be caused by mental distress.[41] Some have expressed concern that belief in demonic possession can limit access to health care for the mentally ill.[42] Studies have found that alleged demonic possessions can be related to trauma.[41]

Notable cases of demonic possession

In chronological order:

- Aix-en-Provence possessions (1611)

- Mademoiselle Elizabeth de Ranfaing (1621)

- Loudun possessions (1634)

- Dorothy Talbye trial (1639)

- Louviers possessions (1647)

- The Possession of Elizabeth Knapp (1671)

- George Lukins (1788)

- Antoine Gay (1871)

- Johann Blumhardt (1842)

- Clara Germana Cele (1906)

- Exorcism of Roland Doe (1940)

- Anneliese Michel (1968)

- Michael Taylor (1974)

- Arne Cheyenne Johnson (1981)

Notable frauds

- Martha Brossier (1578)

- Tanacu exorcism (2005)

See also

Notes

- Casiola, Nancy (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion. Detroit: MacMillan Reference USA. p. 8687. ISBN 978-0-02-865733-2.

Spirit possession may be broadly defined as any altered or unusual state of consciousness and allied behavior that is indigenously understood in terms of the influence of an alien spirit, demon, or deity.

- "Hypnosis - Wikipedia". en.m.wikipedia.org. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

-

Jones, Lindsay (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 8687. ISBN 0-02-865733-0.

The anthropologist Erika Bourguignon found that in a sample of 488 societies 74 percent believe in spirit possession. The highest incidence is found in Pacific cultures and the lowest in North and South American Indian cultures.

- "The New Testament". Bible Gateway. 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "Demons and demonology". Jewish Virtual Library. 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- "Midrash". Project Gutenberg. 2004. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "Dybbuk". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- "Dybbuk". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- Amorth, Gabriele (1999). An Exorcist Tells His Story. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780898707106.

- p.25, The Vatican's Exorcists by Tracy Wilkinson; Warner Books, New York, 2007

- The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist by Matt Baglio; Doubleday, New York, 2009.

- New Catholic Encyclopedia Supplement. Detroit, MI: Gale. 2009. p. 359.

- "Bible: New International Version". Bible Gateway. 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- Netzley, Patricia D. (2002). The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Witchcraft. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. pp. 206. ISBN 9780737746389.

- Cuneo, Michael (1999). "Contemporary American Religion". Gale eBooks. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Tennant, Agnieszka (September 3, 2001). "In need of deliverance". Christianity Today. 45: 46–48+. ProQuest 211985417.

- Broedel, Hans Peter (2003). The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft. Great Britain: Manchester University Press. pp. 32–33.

-

- Michael Anthony Sells Early Islamic Mysticism: Sufi, Qurʼan, Miraj, Poetic and Theological Writings Paulist Press, 1996 ISBN 978-0-809-13619-3 page 143

- Islam and rationality : the impact of al-Ghazālī : papers collected on his 900th anniversary. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. 2005. p. 103. ISBN 978-9-004-29095-2.

- Dein, S. (2013). "Jinn and mental health: Looking at jinn possession in modern psychiatric practice". The Psychiatrist. 37 (9): 290–293. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.113.042721. S2CID 29032393.

- Dreaming in Christianity and Islam: Culture, Conflict, and Creativity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. 2009. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-813-54610-0.

- Rassool, G. Hussein (2015). Islamic Counselling: An Introduction to theory and practice. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-44124-3.

- Al-Krenawi, A. & Graham, J.R. Clinical Social Work Journal (1997) 25: 211. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025714626136

- Meldon, J.A. (1908). "Notes on the Sudanese in Uganda". Journal of the Royal African Society. 7 (26): 123–146. JSTOR 715079.

- Szombathy, Zoltan, “Exorcism”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 15 November 2019<http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_26268> First published online: 2014 First print edition: 9789004269637, 2014, 2014-4

- Hinich Sutherland, Gail (2013). "Demons and the Demonic in Buddhism". Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195393521-0171. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- "Tibetan Buddhist Psychology and Psychotherapy". Tibetan Medicine Education center. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- Kinnard, Jacob (2006). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practice. Gale Virtual Reference Library: Gale.

- Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 530–531, 550, 829. ISBN 9780691157863.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Four maras". Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Verter, Bradford (1999). Contemporary American Religions. Gale eBooks: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 187.

- Robbins, Joel (2004). "The globalization of pentecostal and charismatic Christianity". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33: 117–143. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093421. ProQuest 199862299.

- Pfeifer, S. (1994). Belief in demons and exorcism in psychiatric patients in Switzerland. British Journal of Medical Psychology 4 247-258.

- Tajima-Pozo, K.; Zambrano-Enriquez, D.; De Anta, L.; Moron, M. D.; Carrasco, J. L.; Lopez-Ibor, J. J.; Diaz-Marsá, M. (February 15, 2011). "Practicing exorcism in schizophrenia". BMJ Case Reports. 2011: bcr1020092350. doi:10.1136/bcr.10.2009.2350. PMC 3062860. PMID 22707465.

- Ross, C. A.; Schroeder, E.; Ness, L. (2013). "Dissociation and symptoms of culture-bound syndromes in North America: A preliminary study". Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 14 (2): 224–225. doi:10.1080/15299732.2013.724338. PMID 23406226.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. pp. 293. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- Beyerstein, Barry L. (1995). Dissociative States: Possession and Exorcism. In Gordon Stein (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 544-552. ISBN 1-57392-021-5

- Bhavsar, Vishal; Ventriglio, Antonio; Bhugra, Dinesh (2016). "Dissociative trance and spirit possession: Challenges for cultures in transition". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 70 (12): 551–559. doi:10.1111/pcn.12425. PMID 27485275.

- Henderson, J. (1981). Exorcism and Possession in Psychotherapy Practice. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 27: 129-134.

- Hecker, Tobias; Braitmayer, Lars; Van Duijl, Marjolein (2015). "Global mental health and trauma exposure: The current evidence for the relationship between traumatic experiences and spirit possession". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 6: 29126. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.29126. PMC 4654771. PMID 26589259.

- Karanci, A. Nuray (2014). "Concerns About Schizophrenia or Possession?". Journal of Religion and Health. 53 (6): 1691–1692. doi:10.1007/s10943-014-9910-7. PMID 25056667.

Further reading

- Calmet, Augustine (1751). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- Forcén, Carlos Espí; Forcén, Fernando Espí. (2014). Demonic Possessions and Mental Illness: Discussion of Selected Cases in Late Medieval Hagiographical Literature. Early Science and Medicine 19: 258-79.

- Hartwell, Abraham (1599). A True Discourse Upon the Matter of Martha Brossier of Romorantin, pretended to be possessed by a Devil. 2018. ISBN 1987654439.

- McNamara, Patrick, (2011). Spirit Possession and Exorcism: History, Psychology, and Neurobiology. 2 volumes, Praeger. Santa Barbara, California.

- Westerink, Herman. (2014). Demonic Possession and the Historical Construction of Melancholy and Hysteria. History of Psychiatry 25: 335-349.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Demonic possession |

- Catholic Encyclopedia "Demonical Possession"

- Andrew Lang, Demoniacal Possession, The Making of Religion, (Chapter VII), Longmans, Green, and Co., London, New York and Bombay, 1900, pp. 128–146.