Oslo Airport, Fornebu

Oslo Airport, Fornebu (IATA: FBU, ICAO: ENFB) (Norwegian: Oslo lufthavn, Fornebu) was the main airport serving Oslo and Eastern Norway from 1 June 1939 to 7 October 1998. It was then replaced by Oslo Airport, Gardermoen and the area has since been redeveloped. The airport was located at Fornebu in Bærum, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from the city center. Fornebu had two runways, one 2,370-metre (7,780 ft) 06/24 and one 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) 01/19, and a capacity of 20 aircraft. In 1996, the airport had 170,823 aircraft movements and 10,072,054 passengers. The airport served as a hub for Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS), Braathens SAFE and Widerøe. In 1996, they and 21 other airlines served 28 international destinations. Due to limited terminal and runway capacity, intercontinental and charter airlines used Gardermoen. The Royal Norwegian Air Force retained offices at Fornebu.

Oslo Airport, Fornebu Oslo lufthavn, Fornebu | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||

| Operator | Norwegian Civil Airport Administration | ||||||||||||||

| Serves | Oslo, Norway | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Fornebu, Bærum | ||||||||||||||

| Hub for |

| ||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 56 ft / 17 m | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 59°53′N 010°37′E | ||||||||||||||

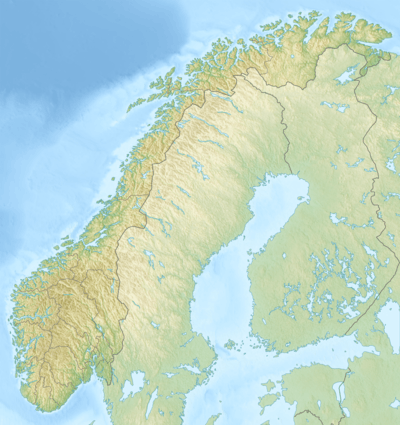

| Map | |||||||||||||||

FBU Location within Norway | |||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Statistics (1996) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

No longer operational | |||||||||||||||

The airport opened as a combined sea and land airport, serving both domestic and international destinations. It replaced the land airport at Kjeller and the sea airport at Gressholmen. In 1940, it was taken over by the German Luftwaffe, but civilian air services began again in 1946 and it was then taken over by the Norwegian Civil Airport Administration. The airport at first had three runways, each at 800 metres (2,600 ft), but these were gradually expanded, first the north–south runway and finally the east–west one to the current length in 1962. The same year the terminal moved south to the final location. A large-scale expansion to the terminal was made during the 1980s.

Facilities

At the time of closing, the airport consisted of a single terminal with three satellites: two domestic and one international. The service building had three stories, one for arrival, one for departure and one for administration. Airplane capacity at the airport was 20 craft;[1] five planes parked at the international terminal could be served with jetbridges, while passengers had to walk outdoors to get to domestic planes. The airport terminals were 36,000 square metres (390,000 sq ft), of which 16,000 square metres (170,000 sq ft) were for the public.[2] In the main hall of the terminal were two murals made by Kai Fjell, both which have been preserved. The largest was the 310-square-metre (3,300 sq ft) Arrival and Departure which was completed in 1968 and covered three stories.[3]

At the north part of the airport, located where the former main terminal was until 1964, were the offices of the Air Force and Fred. Olsen Airtransport, the main hangar for Braathens SAFE, as well as mechanical facilities for SAS and Fred. Olsen. The fire station and snowplowing facilities were also located there, along with the main radar center. All the terminal buildings built until the early 1960s were still intact until the closing of the airport.[4]

In 1989, about 5,500 people worked at Fornebu. Of these, 3,600 worked for the airlines, including ground services. The airport administration had 350 employees, including administration, air control, fire fighters, meteorology and maintenance. The remaining 500 people worked for other public offices, including the police and customs, as well as service employees working for private companies involved with passenger services.[2]

Fornebu had two runways: a main 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) east–west runway and a secondary 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) north–south. Only the main runway was used under ordinary weather conditions, with the north–south runway only being used if there was strong winds from the north and for general aviation, helicopters and ambulance aircraft.[5] The main runway was equipped with instrument landing system category 1.[6] Under ordinary weather conditions, flights to Fornebu were to, as soon as possible, divert southwards along the Oslo Fjord to avoid noise pollution to residential areas. However, when necessary, a direct approach could be made eastwards from Drammen or westwards from Grefsenåsen.[7] Until 1996, Oslo Air Traffic Control Center (Oslo ATCC) was located at Fornebu. It had the responsibility to oversee all air traffic in southeastern Norway, bordering to Dovre in the north, almost to Stavanger in the west, halfway to Stockholm to the east and almost to Denmark in the south.[8]

Since Fornebu is located on a peninsula, all transport to the airport needed to go via Lysaker. A branch from the motorway European Route E18 allowed access to the airport. Lysaker Station is on the Drammen Line, and was served by both local and regional trains, including services to Oslo Central Station. In addition, Stor-Oslo Lokaltrafikk offered bus transport to the airport from Asker and Bærum, including Lysaker. A limited number of services were extended to Snarøya. An airport coach connected the airport to the city center.[9]

Airlines and destinations

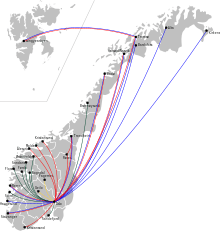

Blue = Scandinavian Airlines System

Red = Braathens SAFE

Green = Widerøe

Yellow = Other

In 1996, the airport had 170,823 aircraft movement and 10,072,054 passengers, making it the busiest airport in the country.[10] It served as the main hub for Braathens SAFE, one of three main hubs for SAS and as one of many for Widerøe.[11][12][13]

Prior to 1 April 1994, all air transport in Norway was restricted to airlines that had received concession from the ministry. On the primary domestic routes, the traffic was split between SAS and Braathens SAFE, although both had services to Trondheim and Stavanger. SAS had a monopoly to Bergen and Northern Norway (Alta, Bardufoss, Bodø, Harstad/Narvik, Kirkenes, Longyearbyen and Tromsø), while Braathens SAFE had a monopoly to the other primary airports in Southern Norway (Haugesund, Kristiansand, Kristiansund, Molde, Røros and Ålesund).[12] Widerøe had a monopoly on the regional state-supported routes (Brønnøysund, Florø, Førde, Sandane, Sogndal and Ørsta/Volda), and also served Stord and Sandefjord.[13]

Following Norway joining the European Economic Area (EEA), the airline industry was deregulated, allowing any airline from any EEA member country to make domestic or international flights to Norway. However, by 1994 there was no available slots at Fornebu during the morning and evening rush hours, limiting the number of new routes that could be established. After the deregulation, Fornebu could not offer slots to new airlines, and SAS and Braathens could not establish as many competing routes as they wanted to.[14] However, domestic services were provided by both SAS and Braathens SAFE to Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim, Bodø, Harstad/Narvik, Tromsø and Longyearbyen. The remaining domestic airports were only served by the incumbent.[15] In addition, Teddy Air offered services to Fagernes.[16]

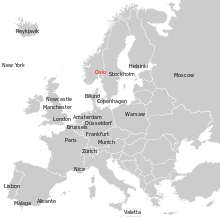

International services were provided by 21 airlines to 28 destinations. SAS had international flights to Amsterdam, Brussels, Billund, Copenhagen, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Helsinki, London-Heathrow, Manchester, Munich, New York, Nice, Paris, Stockholm and Zurich.[11] Braathens SAFE offered international services to Alicante, Billund, London-Gatwick, Málaga, Newcastle and Stockholm.[12] Lufthansa offered flights to Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Munich.[11] Other European airlines that provided services to their main hubs included Aeroflot (Moscow-Sheremetyevo), Air France (Paris-Charles de Gaulle), Air Malta (Valletta), TAP Air Portugal (Lisbon), AirUK (London-Stansted), Alitalia (Milan), British Airways (London-Heathrow), Dan-Air (London-Gatwick), Delta Air Lines (New York-JFK), Iberia (Madrid) and (Barcelona), Icelandair (Reykjavík), KLM (Amsterdam), LOT Polish Airlines (Warsaw), Pan Am (New York-JFK) and Sabena (Brussels).[17][18]

History

Background

Aviation in Oslo started in 1909, when Carl Cederström of Sweden made exhibition flights from fields at Etterstad. Following this, the Norwegian Army decided that it needed a military land airport, and established itself at Kjeller, outside Oslo, in 1912. Kjeller Airport served as the main airport for Norway until the 1930s, being the main base of the newly established Norwegian Army Air Service and the first place to have air services.[19]

In 1918, the first Norwegian airline, Det Norske Luftfartrederi, was established, and plans were made to start flying to Trondheim. The following year, civil aviation was discussed in the Norwegian Parliament for the first time. Norsk Luftfartsrederi wanted to start seaplane routes from Oslo, and applied to the state to be allowed to lease 2 hectares (4.9 acres) of the island Lindøya for 99 years. The Oslo Port Authority recommended that the application be denied, since it was already in negotiations with the state to purchase the island and seaplane services would interfere with ship traffic. The ministry recommended a ten-year lease. Sam Eyde, who was a member of parliament, recommended that the state should be responsible for all airports, and suggested a state-owned seaplane airport be built at Gressholmen. However no money was granted for construction of the airport until 1926, when Gressholmen Airport opened.[20] Gressholmen was served by Norsk Luftfartsrederi and Deutsche Luft Hansa.[21]

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, the politicians became less satisfied with the solution. Kjeller was considered too far away from the city center (about 20 kilometres (12 mi), but along the mainline railway), while travel to Gressholmen needed to be made by ferry. The politicians also wanted to have a combined land- and seaplane airport, and it had become clear that serving Gressholmen was interfering with ship traffic. A committee was established to look into the matter. While considering many locations, it made detail surveys of only two places: Ekeberg, located southeast of the city center, and Fornebu, to the southwest.[22]

Construction

At the time, Fornebu was a mostly unpopulated area. Until 1907, a lumber mill was located at Snarøya on the southern tip. From 1921, Snarøya had received a coach service, and had grown with many single dwellings. About 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) northeast of Fornebu is the town of Lysaker, which had a railway station on the Drammen Line. The committee decided to purchase 90 hectares (220 acres) on the northern part of the peninsula. The Fornebu solution would be more expensive, but would yield a larger airport and better landing conditions. The formal decision to build the airport was taken in 1934.[23]

It was the Municipality of Oslo which built the airport, having bought the land from the Municipality of Bærum. Construction was to serve as work creation for the unemployed, and workers were selected based on how long they had been unemployed and the number of people in their family. Because the need for workplaces was greatest in the winter, most of the construction was done during the winters of 1935, 1936 and 1937. Not until 1937 was a normal 48-hour week throughout the year introduced. 1,000,000 cubic metres (35,000,000 cu ft) of rock was blasted and, along with garbage from Oslo, used to fill in the swamps and depressions. Because of the delays, plans were changed and three runways were built, two 800 metres (2,600 ft) long and one 700 metres (2,300 ft) long. The airport was equipped with a control tower; administration building; a hangar with a workshop; and a service building. Docks for seaplanes were constructed about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) to the south, on the east shore of the peninsula.[24]

In 1934, there were three domestic airlines in Norway: Det Norske Luftfartsselskap (DNL), Norske Luftruter and Widerøe's Flyveselskap. All three applied to the state for subsidies to operate routes. DNL applied for a ten-year concession with a 500,000 kr annual subsidy to fly Oslo–Kristiansand–Amsterdam, continuing northwards to Ålesund. Widerøe applied for NOK 265,000 per year for a three-year concession for the seaplane routes Oslo–Bergen and Bergen–Trondheim. Norske Luftruter applied for NOK 250,000 per year for a route from Bergen to Copenhagen via Kristiansand and Oslo. The following year, parliament passed a long-term plan for construction of airports, which would be located in Oslo, Telemark, Kristiansand, Stavanger, Bergen, Ålesund and Trondheim. In each case, the municipalities would have to purchase land and build the airport, but the state would reimburse 50% of the investments. Due to the high cost burden on the municipalities, only Stavanger Airport, Sola and Kristiansand Airport, Kjevik were operational by the time Fornebu opened.[25]

Opening and war

The first aircraft at Fornebu was a Lufthansa Junkers Ju 52 in September 1938. It had flown a scheduled route to Kjeller, and the captain had continued to Fornebu to try the new airport. On 16 April 1939, the seaplane section came into regular use. The first seaplane was a Ju 52 operated by DNL to Copenhagen. The official opening was on 1 June 1939. The first aircraft to land after the official opening was a Douglas DC-2 operated by KLM from Amsterdam. The first departure was on the Danish airline Det Danske Luftfartsselskab, when a Focke-Wulf Fw 200 took off to Copenhagen. The captain made a mistake, and took off from the parking space instead of the runway. In addition to these two routes, Luft Hansa started flights to Germany and DNL flew to Amsterdam. During the fall, DNL also flew from Perth, Scotland, via Oslo to Stockholm, but this route was soon canceled.[26]

As part of the invasion of Norway by Nazi Germany on 9 April 1940, German Luftwaffe-aircraft landed at Fornebu. There was no attempt by the civilian airport authorities to hinder this, such as driving cars onto the runway, although several German aircraft collided with each other during the landing. A KLM aircraft had a scheduled service that morning, and the captain was ordered to leave the passengers, take the crew and return to Oslo. On 12 April, the airport was bombed by the British Royal Air Force. On 14 April, the KLM captain was granted permission to fly back to Amsterdam with the crew, albeit without any passengers. The German military used Fornebu heavily during the war, but it was never of any strategic importance, since it was located far from any battle zones. During the war, the airport officially remained owned by the municipality. By orders of the German authorities, the main north–south runway was expanded to 1,200 metres (3,900 ft), and all facilities not yet built were completed. However, during the war all other runways than the main north–south were taken out of use. At the north end of the runway, the Luftwaffe built several hangars and a prison camp. Prisoners were used to keep the runways free of snow during winter, by marching along them and stomping the snow down.[27]

In May 1945, as German forces were ousted from Norway, the airport was taken over by the Allies and the Royal Norwegian Air Force. None of the civilian airlines were in operation, and the Air Force started flying commercial flights. In addition to previous lines, a route was started to Northern Norway, although it had to be terminated for the winter. Due to the lack of qualified personnel, the international services had to be terminated as well. In early 1946, management of the airport was transferred back to the municipality. Due to the technological development of aviation during the war, the runway needed to be expanded. The 1,200-metre (3,900 ft) runway was sufficient for Douglas DC-3 aircraft, but insufficient for larger Douglas DC-4s. The latter were all used by American Overseas Airways, DNL on its North America routes and British European Airways on its route to London, which were all transferred to Oslo Airport, Gardermoen.[28]

Expansion

On 1 November 1947, Norsk Spisevognselskap established a restaurant at the airport.[29] In 1946, DNL launched plans to expand the north–south runway to 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) by taking into use the whole peninsula. In addition, it wanted a second east–west runway to be built. The state took over ownership of the airport—without compensation—in 1946, albeit with the clause that if the airport ever should close, the real estate should be returned to the municipality. Stavanger Airport had been a candidate for intercontinental travel, but a state committee in 1949 decided that instead this should be shared between Fornebu and Gardermoen. Another committee was established in 1948, and in 1950 it recommended that all airport services in the Oslo region should be concentrated at Gardermoen, and that a new motorway be built to the airport. Among politicians and planners, there were two main ideologies: The first, which dominated in political circles, stated that Fornebu's close proximity to the city center was a key to reaching a market in Oslo and for the growth of the airlines. The second emphasized that, in the long run, Fornebu could not fulfill the requirements of a central airport, and that a better location should be established.[30]

Following the political processes, the north–south runway was extended to 1,600 metres (5,200 ft). With the completion of this, intercontinental traffic was moved from Gardermoen to Fornebu. In 1946, Overseas Scandinavian Airlines System had been established between DNL, DDL and the Swedish Aerotransport.[31] The same year, shipowner Ludvig G. Braathen established Braathens South American and Far East (Braathens SAFE), which started with charter flights using DC-4s. The first civilian route was operated by KLM, who started the route Oslo–Kristiansand–Amsterdam in March 1946. From 1 April, DNL operated a route to Copenhagen, followed a week later with the route via Stavanger to London, using DC-3s. The third DNL route was to Stockholm using Ju 52s, and the fourth via Gothenburg and Copenhagen to Zurich and Marseilles. In May, DNL started routes to Trondheim and Tromsø, and later onwards to Kirkenes. It also started a direct service to Copenhagen. In October, routes were established via Kristiansand to Amsterdam, Brussels and Paris. Finally, a route was started via Copenhagen to Prague and to Stavanger. In 1946, DNL had 47,000 passengers (although not all flew through Fornebu). The company operated six DC-3s and five Ju 52s.[32]

In 1947, Icelandair started flights to Reykjavík and the same year British European Airways transferred its London route from Gardermoen to Fornebu.[33] DNL bought three Short Sandringham flying boats which were put into service along the coast as the "Flying Coastal Express". They remained in service from 1947 until May 1950, but proved expensive in operation.[34] In 1949, Braathens SAFE introduced scheduled flights from Fornebu using DC-3s; it had long-haul flights to the Far East, with stops in Amsterdam, Geneva, Rome, Cairo, Basra, Karachi, Bombay, Calcutta and Bangkok before arriving in Hong Kong.[35] Following the establishment of Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) in 1949, all international concessions were transferred to that company, and Braathens SAFE started domestic services, although it kept its existing concessions on international routes until 1954.[36]

Braathens SAFE's first domestic service was via Tønsberg Airport, Jarlsberg to Stavanger, and later a route to Trondheim. These were both operated with Heron aircraft. At first the Trondheim route was flown to Lade, but were quickly transferred to the current airport at Værnes.[37] Loftleiðir started flights to Reykjavík in 1952.[33]

In 1953, work started with expanding the north–south runway to 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) and building a new east–west runway which also was to become 1,800 metres (5,900 ft). The same year a new commission was established, which in 1957 recommended that the east–west runway be expanded to 3,300 metres (10,800 ft) and the north–south runway to 2,150 metres (7,050 ft). Local residents and politicians were opposed to the expansion plans, and Akershus County Council voted against them. The ministry then chose to expand the east–west runway to only 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) and leave the north–south runway untouched. The plans would allow the east–west runway to be expanded to 2,800 metres (9,200 ft) in the future, if necessary. The north–south runway had difficult landing conditions, in part because of the residential areas north of the line. From 1959, the ministry denied jet aircraft from using the then longer runway.[38] In the 1950s, SAS started using Convair 440s, while Braathens SAFE took into use Fokker F-27s. Both companies later also took into use Douglas DC-6s.[39]

In 1952, SAS started flights to Bodø Airport and in 1955 to Bergen Airport, Flesland.[39] In 1955, Braathens SAFE also started flights to Kristiansand and Farsund Airport, Lista, and the following year to Notodden Airport, Tuven. That year also saw some of its Trondheim flights land at Hamar Airport, and in 1957 at Røros Airport.[40] In 1958, Ålesund Airport, Vigra was opened and became served by Braathens SAFE.[41] The Røros stops were terminated in 1958, but reinstated in 1963 after the runway had been extended. The Hamar stops were permanently terminated in 1959.[42]

In 1960, Finnair started flying to Helsinki, although direct flights were not introduced until 1971.[33] After 1962, the east–west runway became the main runway. Along with the runway expansion, a new service building, with a capacity for 2 million passengers, was opened in 1964. It was located about half a kilometer (quarter of a mile) south of the former terminal. Designed by Odd Nansens Arkitektkontor, it had two stories, one for arrivals and one for departures, and two wings, one for domestic and one for international flights. It included a central hall that had a panorama view over the aircraft.[43] The expanded facilities allowed SAS to take into use Sud Aviation Caravelle jets on the Copenhagen routes, although they were also occasionally used to Bodø.[44]

Cramped quarters

Three airports were opened in Finnmark in 1963, all served by SAS: Alta Airport, Kirkenes Airport, Høybuktmoen and Lakselv Airport, Banak. The following year, SAS also started flights to Tromsø Airport. In 1966, Lufthansa started flights to Hamburg, and later also introduced services to Düsseldorf, Frankfurt and Munich. During the 1960s, SAS introduced Caravelles on most of the domestic routes.[17]

During the 1970s, Douglas DC-8s were also taken into use. Pan American World Airways had flights to New York City from 1967 to 1973 and from 1976 to 1978. Braathens SAFE started taking delivery of Boeing 737-200s and Fokker F-28s in 1969, and these gradually took over most of the domestic routes.[45] In 1970, Air France and Swissair started flying to Fornebu from Paris and Zurich, respectively. They were supplemented by Aeroflot's Moscow route in 1972.[46]

In 1971, a state committee recommended that Gardermoen be expanded to take a larger share of the traffic from Fornebu. At the same time, a new main airport was eventually to be built at Hobøl. From 1971, charter flights were moved to Gardermoen, although SAS and Braathens SAFE were granted dispensation so they only needed to serve one Oslo airport.[47] On 1 July 1971, Widerøe also started serving domestic routes to Fornebu, with the opening of a regional airport in Sogn og Fjordane. These routes were served using de Havilland Canada Twin Otter and later de Havilland Canada Dash 7 aircraft, although regular services to all airports were not introduced until the late 1970s, with the introduction of the Dash 7.[48] The last four primary airports were opened during the 1970s. Braathens SAFE started flights to Kristiansund Airport, Kvernberget in 1972, Molde Airport, Årø in 1972 and Harstad/Narvik Airport, Evenes in 1973. In 1975, SAS started flights to Haugesund Airport, Karmøy.[49]

During the 1980s, the airport was again deemed too small. In 1983, all charter flights operated by SAS and Braathens were forced to move to Gardermoen.[50] Additional foreign services were introduced, namely Sabena to Brussels in 1985, Dan-Air to London-Gatwick and Newcastle in 1986 and Alitalia to Milan in 1988. During a period of reconstruction at Gardermoen, Trans World Airlines also served Fornebu, and the same year Pan American reintroduced its route to New York.[46] Air Europe also started to fly from London-Gatwick to Fornebu.[51] An additional storey was added to the service building, allowing office space to be moved there and free up space for check-in and traveler service on the two main storeys. Two satellites were built for the domestic terminal, one each for Braathens SAFE and SAS, allowing increased waiting area for travelers. The international terminal was expanded with a five-gate pier with jetbridges. A multi-story parking house was also built.[52]

Norsk Air started serving Fornebu following the opening of Fagernes Airport, Leirin in 1987.[53] The route was closed within a year, but taken up again by Coast Air in 1990.[54] From 1996, the route was taken over by Teddy Air.[16]

In 1989, Braathens SAFE started its first international scheduled service since 1960, from Fornebu to Billund in Denmark. Two years later, the company started flying to Newcastle, after Dan-Air had withdrawn from the route, and to Malmö in Sweden. That year also saw the start of Norway Airlines, who started a base at Fornebu and offered flights to London-Gatwick, as well as to Stockholm, in cooperation with Transwede, and to Copenhagen, in cooperation with Sterling Airlines. In 1992, both Norway Airlines and Dan-Air went bankrupt, and Braathens SAFE started flights to London-Gatwick. It terminated the Malmö route in 1994.[55] After the deregulation, Braathens SAFE also introduced flights to Alicante, Málaga, Rome and Stockholm.[12] Widerøe introduced international services to Gothenburg and Berlin.[13]

In 1994, the domestic and international flights to the European Union were deregulated, and the number of international services increased and Fornebu received airlines such as Air Malta, Air Portugal, AirUK and LOT Polish Airlines. Other airlines to fly from Fornebu during the 1980s and 1990s includes Delta Air Lines, Northwest Orient and Tower Air.[18] Domestically, Braathens SAFE introduced flights to Bergen, Bodø, Harstad/Narvik and Tromsø.[15]

Closing

During the 1960s, a political debate started concerning whether or not a new main airport should be built for Oslo and Eastern Norway. A government report launched in 1970, suggested surveys for five locations: Gardermoen, Hurum, Askim, Nesodden and Ås. Hobøl was preliminarily selected and areas reserved for a future airport. During the 1970s, the Labour Party became concerned that Hobøl was located too centrally in relation to the growth areas around Oslo, and instead wanted to use Gardermoen, in an attempt to force the population growth further north. Commercial interests and the airlines supported Hobøl. In 1983, Parliament decided to abandon the plans for Hobøl and continue with a divided solution. Fornebu would be expanded, and all charter traffic be moved to Gardermoen. From 1988, all international traffic would also be moved, making Fornebu a purely domestic airport.[56]

Increased traffic in the mid-1980s changed the politician's interests, and in 1988 Parliament voted to build a new main airport at Hurum, located on the same side of Oslo as Fornebu, but further away. However, new weather data showed that Hurum was unsuitable, and the location was discarded. There were accusations that the data was fabricated to manipulate the political decision. In 1992, parliament made a final vote that started construction of a new airport at Gardermoen and mandated the closure of Fornebu.[57]

Financing of the airport at Gardermoen would be done through a state loan issued to a limited company owned by the Civil Airport Administration. This company would build and operate Gardermoen, but from 1 January 1997 it also took over operation of Fornebu. After the last aircraft took off from Fornebu on 7 October 1998, 300 people spent the night transporting 500 truckloads of equipment from Fornebu to Gardermoen. The new airport opened on the morning of 8 October 1998.[57]

Some locals wanted to keep Fornebu as a regional airport for the Oslo and Bærum area. The proposal was to keep part of the runway and terminals and allow aircraft such as the Bombardier Dash 8, Fokker 50 and British Aerospace 146 to use the airport. Proponents argued that a similar role was filled by Stockholm-Bromma Airport and Chicago's Midway Airport.[58]

The opening of Gardermoen had a strategic impact on aviation in Norway. Despite the deregulation of the market in 1994, the lack of free slots at Fornebu made it impossible to have free competition, since no new airlines could establish themselves and no new international airlines could fly to Fornebu.[59] Gardermoen allowed this to happen, and from 1 August 1998, Color Air started with flights from Oslo, pressing down prices on domestic routes.[60] Although the airline went bankrupt the following year,[61] the losses for Braathens were so high that it was taken over by SAS.[62] The gap was then filled by Norwegian Air Shuttle.[63]

Redevelopment

Since closing in 1998, the former airport site has been renovated and redeveloped. The headquarter offices of Telenor (NBBJ architects, 2001), regional and international offices for Equinor (formerly Statoil, a-lab architects (no)), Telenor Arena (HRTB architects, 2009), as well as other office and housing projects.[64] Prior to redevelopment, the airport site was used in the music video for Norwegian artist Hanah's 2001 song "Hollywood Lie".

Several buildings from the former airport have been preserved, including the control tower, the terminal building and two distinctive aircraft hangars. In the western part of the peninsula, a 50m x 20m section of former runway 06/24 has been restored in memory of the airport. In the northwest, the seaplane base "Kilen Sjøflyklubb" is still in operation.

Accidents and incidents

- On 26 May 1946, a DNL Junkers Ju 52 en route to Stockholm crashed into the houses at Halden Terrasse after take-off, due to a technical error on the aircraft. All people on board were killed, but no-one on the ground.[65]

- On 20 November 1949, a Dutch DC-3 crashed in Hurum while approaching Fornebu. All but one of the passengers, plus all the crew, died.[66]

- On 14 April 1963, Vickers Viscount TF-ISU Hrímfaxi of Icelandair Flugfélag Islands crashed at Nesøya on approach to Fornebu. All 12 people on board were killed.[66][67]

- On 23 December 1972, Braathens SAFE Flight 239, with a Fokker F-28 from Ålesund to Oslo, crashed in Asker during approach to Fornebu. Forty people were killed, while five people survived. This was the first-ever fatal accident with an F-28, and until 1989 the deadliest air accident in Norway.[68]

- Braathens SAFE Flight 139 occurred on 21 June 1985, when a Boeing 737-200 from Braathens SAFE en route from Trondheim Airport, Værnes to Fornebu was hijacked by a drunk student who demanded to talk to the prime minister and minister of justice. The plane landed at Fornebu, and the hijacker eventually surrendered his gun in exchange for more beer. No-one was injured in the incident.[69][70]

Notes

- Wisting, 1989: 80

- Wisting, 1989: 99

- "Konservering og restaurering av Kai Fjells malerier på Fornebu" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- Wisting, 1989: 92

- Wisting, 1989: 60

- Bredal, 1998: 176

- Wisting, 1989: 94–97

- Malmø, 1997: 94

- Wisting, 1989: 90

- Malmø, 1997: 77

- "European Routes". Scanorama. Scandinavian Airlines System. September: 112–115. 1997.

- "Braathens SAFEs rutenett". Wings of Norway. Braathens SAFE. Winter: 58. 1997.

- "Widerøes totale rutenett". Perspektiv. Widerøe. 4: 52. 1997.

- Bredal, 1998: 164–165

- Tjomsland and Wilsberg, 1995: 340

- Norwegian Ministry of Transport and Communications (14 June 1996). "Teddy Air AS får enerett" (in Norwegian). Government.no. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- Wisting, 1989: 74–76

- Malmø, 1997: 25–26

- Wisting, 1989: 10–12

- Wisting, 1989: 13–20

- Wisting, 1989: 30

- Wisting, 1989: 20–22

- Wisting, 1989: 22–26

- Wisting, 1989: 26–33

- Wisting, 1989: 31–35

- Wisting, 1989: 35–41

- Wisting, 1989: 42–46

- Wisting, 1989: 47–48

- Just (1949): 72

- Wisting, 1989: 48–49

- Wisting, 1989: 53–55

- Wisting, 1989: 67–68

- Wisting, 1989: 74

- Wisting, 1989: 69–70

- Tjomsland and Wilsberg, 1995: 45

- Wisting, 1989: 70–71

- Wisting, 1989: 71

- Wisting, 1989: 53–58

- Wisting, 1989: 71–72

- Tjomsland and Wilsborg, 1995: 105–106

- Tjomsland and Wilsborg, 1995: 114

- Tjomsland and Wilsborg, 1995: 106

- Wisting, 1989: 58–61

- Wisting, 1989: 72

- Wisting, 1989: 72–73

- Wisting, 1989: 76

- Wisting, 1989: 63–64

- Arnesen, 1984: 117–119

- Malmø, 1997: 65

- Wisting, 1989: 64–65

- Tjomsland and Wilsberg, 1995: 300

- Wisting, 1989: 80–83

- "NorskAIR skal fly på Valdres". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 21 October 1987. p. 38.

- ""Valdresflya" på vingene fra 3. september". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 14 August 1990. p. 4.

- Tjomsland and Wilsberg, 1995: 295–304

- Bredal, 1998: 17–20

- Bredal, 1998: 23–29

- Blindheim, Richard (27 October 1998). "Fornebu – ikke for sent!". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 35.

- Valestrand, Terje (19 January 1998). "Color Air: Ingen politisk sak". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). p. 6.

- Lillesund, Geir (5 August 1998). "Mange ledige seter Oslo-Ålesund" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. p. 10.

- "Color-avviklingen: – Som en bombe på de ansatte" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 27 September 1999.

- Meyer, Henrik D. (23 October 2001). "SAS får kjøpe Braathens". Dagens Næringsliv (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- Dahl, Flemming (17 April 2002). "Lavprisselskap kan ta av". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 23.

- "Fornebu –transformation of an airport". Guiding Architects. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Wisting, 1989: 48

- Malmø, 1997: 118

- "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Tjomsland and Wilsberg, 1996: 48

- Tjomsland and Wilsberg (1995): 279

- "21 June 1985". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oslo Airport, Fornebu. |

- Arnesen, Odd (1984). På grønne vinger over Norge (in Norwegian). Widerøe's Flyveselskap.

- Bredal, Dag (1998). Oslo lufthavn Gardermoen: Porten til Norge (in Norwegian). Schibsted. ISBN 82-516-1719-7.

- Just, Carl (1949). A/S Norsk Spisevognselskap 1919–1949 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Norsk Spisevognselskap. OCLC 40310643.

- Malmø, Morten (1997). Norge på vingene! (in Norwegian). Oslo: Andante Forlag. ISBN 82-91056-13-7.

- Tjomsland, Audun and Kjell G. Wilsberg (1995). Mot alle odds (in Norwegian). Braathens SAFE. ISBN 82-990400-1-9.

- Wisting, Tor (1989). Oslo lufthavn Fornebu 1939–1989 (in Norwegian). TWK-forlaget. ISBN 82-90884-00-1.

Further reading

- Guhnfeldt, Cato (1990). Fornebu 9. april (in Norwegian). Oslo: Wings. ISBN 82-992194-1-8.