Muslims (ethnic group)

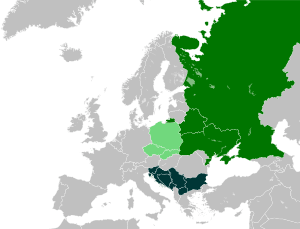

Muslims (in all South Slavic languages: Muslimani, Муслимани) as a designation for a particular ethnic group, refers to one of six officially recognized constituent peoples of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The term was adopted in 1971, as an official designation of ethnicity for Yugoslav Slavic Muslims, thus grouping together a number of distinct South Slavic communities of Islamic ethnocultural tradition, among them most numerous being the modern Bosniaks of Bosnia and Herzegovina, along with some smaller groups of different ethnicity, such as Gorani and Torbeši. This designation did not include Yugoslav non-Slavic Muslims, such as Albanians, Turks and Romani.[2]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 100,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 27,553 (2011) | |

| 22,301 (2011) | |

| 20,537 (2011) | |

| 12,101 (2013)[1] | |

| 10,467 (2002) | |

| 7,558 (2011) | |

| 2,553 (2002) | |

| 97 | |

| Languages | |

| Bosnian and other Serbo-Croatian languages, Macedonian, along with Albanian, Turkish, Bulgarian | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bosniaks, Gorani, Macedonian Muslims, Pomaks, Torbeš | |

After the breakup of Yugoslavia (1991–1992) a majority of Slavic Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted the "Bosniak" ethnic designation in 1993, and they are today constitutionally recognized as one of three constituent peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Approximately 100,000 people across the former Yugoslavia still consider themselves to be Muslims in an ethnic sense. Remaining ethnic Muslims are most numerous in Serbia and they are constitutionally recognized as a distinctive ethnic minority in Montenegro.[3]

Background

Up until the 19th century, the word Bosniak (Bošnjak) came to refer to all inhabitants of Bosnia regardless of religious affiliation; terms such as "Boşnak milleti", "Boşnak kavmi", and "Boşnak taifesi" (all meaning, roughly, "the Bosnian people"), were used in the Ottoman Empire to describe Bosnians in an ethnic or "tribal" sense. After the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, the Austrian administration officially endorsed Bošnjaštvo ('Bosniakhood') as the basis of a multi-confessional Bosnian nation. The policy aspired to isolate Bosnia and Herzegovina from its irredentist neighbors (Orthodox Serbia, Catholic Croatia, and the Muslims of the Ottoman Empire) and to negate the concept of Croatian and Serbian nationhood which had already begun to take ground among Bosnia and Herzegovina's Catholic and Orthodox communities, respectively.[4][5] Nevertheless, in part due to the dominant standing held in the previous centuries by the native Muslim population in Ottoman Bosnia, a sense of Bosnian nationhood was cherished mainly by Muslim Bosnians, while fiercely opposed by nationalists from Serbia and Croatia who were instead opting to claim the Bosnian Muslim population as their own, a move that was rejected by most of them.[6] After World War I, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later "Kingdom of Yugoslavia") was formed and it recognized only those three nationalities in its constitution.

History

After World War II, in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the Bosnian Muslims continued to be treated as a religious group instead of an ethnic one.[7] Aleksandar Ranković and other Serb communist members opposed the recognition of Bosniak nationality.[8] Muslim members of the communist party continued in their efforts to get Tito to support their position for recognition.[8][9][10] Nevertheless, in a debate that went on during the 1960s, many Bosniak communist intellectuals argued that the Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina are in fact a distinct native Slavic people that should be recognized as a nation. In 1964, the Fourth Congress of the Bosnian branch of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia assured their Bosniaks membership the Bosniaks' right to self-determination will be fulfilled, thus prompting the recognition of Bosnian Muslims as a distinct nation at a meeting of the Bosnian Central Committee in 1968, however not under the Bosniak or Bosnian name, as opted by the Bosnian Muslim communist leadership.[7][11] As a compromise, the Constitution of Yugoslavia was amended to list "Muslims" in a national sense; recognizing a constitutive nation, but not the Bosniak name. The use of Muslim as an ethnic denomination was criticized early on, especially on account of motives and reasoning, as well as disregard of this aspect of Bosnian nationhood.[12] Following the downfall of Ranković, Tito had also changed his view and stated that recognition of Muslims and their national identity should occur.[8] In 1968 the move was protested in the Serbia and by Serb nationalists such as Dobrica Ćosić.[8] The change was opposed by the Macedonian branch of the Yugoslav Communist Party.[8] They viewed Macedonian speaking Muslims as Macedonians and were concerned that statewide recognition of Muslims as a distinct nation could threaten the demographic balance of the Macedonian republic.[8]

Sometimes other terms, such as Muslim with capital M were used, that is, "musliman" was a practicing Muslim while "Musliman" was a member of this nation (Serbo-Croatian uses capital letters for names of peoples but small for names of adherents).

After the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, the majority of these people, around two million, mostly located in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the region of Sandžak, declare as ethnic Bosniaks (Bošnjaci, sing. Bošnjak). On the other hand, some still use the old name Muslimani (Muslims), mostly outside Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The election law of Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, recognizes the results from 1991 population census as results referring to Bosniaks.[13][14]

Population

- In Serbia, according to the 2011 census there were 22,301 Muslims by nationality, 145,278 Bosniaks as well as few Serb Muslims (ethnic Serbs who are Muslims (adherents of Islam) by their religious affiliation).[15]

- In Montenegro census of 2011, 20,537 (3.3%) of the population declared as Muslims by nationality; while 53,605 (8.6%) declared as Bosniaks; while 175 (0.03%) Muslims by confession declared as Montenegrin Muslims.[16] Muslims and Bosniaks are considered as a two separate ethnic groups, and both of them have their own separate National Councils. Also to mention, many Muslims consider themselves as Montenegrins of Islamic faith. National Council of Muslims of Montenegro insists their mother tongue is Montenegrin.[17]

- In 2002 Slovenia census, 21,542 persons identified as Bosniaks (thereof 19,923 Bosniak Muslims); 8,062 as Bosnians (thereof 5,724 Bosnian Muslims), 2,804 were Slovenian Muslims. while 9,328 chose Muslims by nationality.[18]

- In North Macedonia, the census of 2002 registered 17,018 (1,15%)[19] Bosniaks and 2,553 (0.13%) Muslims by nationality. There is also a few number of Macedonian Muslims a minority religious group within the community of ethnic Macedonians who are Muslims by their religious affiliation. It is also important to note that most members of Pomaks and Torbeš ethnicities also declared as Muslims by nationality prior to 1990.

- In Croatia, according to the census of 2011 there were 6,704 Muslims by nationality, 27,959 Bosniak Muslims, 9,594 Albanian Muslims, 9,647 Croat Muslims and 5,039 Muslim Roma. The Bosniaks of Croatia are the largest minority practicing Islam in Croatia.[20][21][22][23]

See also

References

- "Popis 2013 BiH". www.popis.gov.ba. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Dimitrova 2001, p. 94-108.

- Đečević, Vuković-Ćalasan & Knežević 2017, p. 137-157.

- Donia & Fine 1994.

- Velikonja 2003, p. 130-135.

- Publications, Europa (2003). Central and South-Eastern Europe 2004, Volume 4, Routledge, p 110. ISBN 9781857431865.

- Banac 1988, p. 287–288.

- Bećirević, Edina (2014). Genocide on the Drina River. Yale University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9780300192582.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Indiana University Press. p. 286. ISBN 0-253-34656-8. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- Sancaktar, Caner (1 April 2012). "Historical Construction and Development of Bosniak Nation". Alternatives: Turkish Journal of International Relations. 11: 1–17. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- Kostić, Roland (2007). Kostic, Roland 2007. Ambivalent Peace: External Peacebuilding, Threatened Identity and Reconciliation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Report No. 78, Department of Peace and Conflict Research and the Programme for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden, p.65. ISBN 9789150619508.

- Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka. Sarajevo: BZK Preporod. ISBN 9958-815-00-1

- "Election law of Bosnia and Herzegovina" (PDF).

- "CONSTITUTION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA" (PDF). The Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- 2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia

- "MONTENEGRO STATISTICAL OFFICE, RELEASE, No: 83, 12 July 2011, Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011, p. 6" (PDF). Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Kurpejović 2018, p. 48, 73, 102, 143-144.

- "Population by religion and ethnic affiliation, Slovenia, 2002 Census". Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Statistics Office of Republic of Macedonia - Државен завод за статистика:Попис на населението, домаќинствата и становите во Република Македонија, 2002: Дефинитивни податоци (PDF) (in Macedonian)

- Population by ethnicity - 2001 Croatian Census (in Croatian)

- "SAS Output". www.dzs.hr. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "Central Bureau of Statistics". www.dzs.hr. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "4. Population by ethnicity and religion". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

Further reading

- Banac, Ivo (1988) [1984]. The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics (2. ed.). Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801494931.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ćerić, Salim (1968). Muslimani srpskohrvatskog jezika. Sarajevo: Svjetlost.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dimitrova, Bohdana (2001). "Bosniak or Muslim? Dilemma of one Nation with two Names" (PDF). Southeast European Politics. 2 (2): 94–108.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Đečević, Mehmed; Vuković-Ćalasan, Danijela; Knežević, Saša (2017). "Re-designation of Ethnic Muslims as Bosniaks in Montenegro: Local Specificities and Dynamics of This Process". East European Politics and Societies and Cultures. 31 (1): 137–157. doi:10.1177/0888325416678042.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donia, Robert J.; Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994). Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9781850652120.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Džaja, Srećko M. (2002). Die politische Realität des Jugoslawismus (1918-1991): Mit besonderer Berücksichtigung Bosnien-Herzegowinas. München: R. Oldenbourg Verlag. ISBN 9783486566598.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Džaja, Srećko M. (2004). Politička realnost jugoslavenstva (1918-1991): S posebnim osvrtom na Bosnu i Hercegovinu. Sarajevo-Zagreb: Svjetlo riječi. ISBN 9789958741357.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jović, Dejan (2013). "Identitet Bošnjaka/Muslimana". Politička Misao: Časopis Za Politologiju. 50 (4): 132–159.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2006). Slovenski muslimani zapadnog Balkana. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2008). Muslimani Crne Gore: Značajna istorijska saznanja, dokumenta, institucije, i događaji. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2011). Kulturni i nacionalni status i položaj Muslimana Crne Gore. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2014). Analiza nacionalne diskriminacije i asimilacije Muslimana Crne Gore. Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore. ISBN 9789940620035.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurpejović, Avdul (2018). Ko smo mi Muslimani Crne Gore (PDF). Podgorica: Matica muslimanska Crne Gore.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781603447249.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muslims (ethnic group). |