Macedonian Muslims

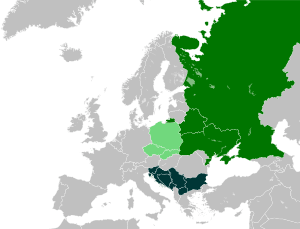

The Macedonian Muslims (Macedonian: Македонци-муслимани, romanized: Makedonci-muslimani), also known as Muslim Macedonians[3] or Torbeši (Macedonian: Торбеши), and in some sources grouped together with Pomaks,[4][5][6][7] are a minority religious group within the community of ethnic Macedonians in North Macedonia who are Muslims (primarily Sunni, with Sufism being widespread among the population). They have been culturally distinct from the majority Orthodox Christian Macedonian community for centuries, and are ethnically and linguistically distinct from the larger Muslim ethnic groups in the greater region of Macedonia: the Albanians, Turks and Roms. However, some Torbeši also still maintain a strong affiliation with Turkish identity and with Macedonian Turks.[8] The regions inhabited by these Macedonian-speaking Muslims are Debarska Župa, Oktisi, Drimkol, Reka, and Golo Brdo (in Albania).

Female folk dance of Macedonian Muslims in the village of Gorno Kosovrasti, near Debar | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 40,000–100,000 (2010) 39,555[1][2] (1981) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Macedonian, Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Macedonians, Pomaks, Slavic Muslims, Macedonian Turks, Bulgarians |

Origins

The Macedonian Muslims are largely the descendants of Orthodox Christian Slavs from the region of Macedonia who converted to Islam during the centuries when the Ottoman Empire ruled the Balkans.[9] The various Sufi orders (like the Khalwati, Rifa'is and Qadiris) all played a role in the conversion of the Slavic and Paulician population.[10]

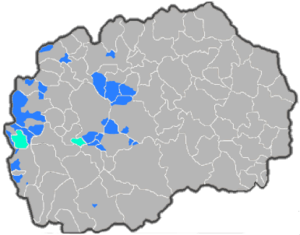

Areas of settlement

The largest concentration of Macedonian Muslims can be found in western North Macedonia and eastern Albania. Most of the villages in Debar regions are populated by Macedonian Muslims. The Struga municipality also holds a large number of Macedonian Muslims who are primarily concentrated in the large village of Labuništa. Further north in the Debar region many of the surrounding villages are inhabited by Macedonian Muslims. The Dolna Reka region is also primarily populated by Macedonian Muslims. They form the remainder of the population which emigrated to Turkey in the 1950s and 1960s. Places such as Rostuša and Tetovo also have large Macedonian Muslim populations. Most of the Turkish population along the western Macedonian border are in fact Macedonian Muslims. Another large concentration of Macedonian Muslims is in the so-called Torbešija which is just south of Skopje. There are also major concentrations of Macedonian Muslims in the central region of the Republic of Macedonia, surrounding the Plasnica municipality and the Dolneni municipality.

| Part of a series on |

| Macedonians |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Macedonia (region) |

| Diaspora |

|

|

|

|

|

Subgroups and related groups |

|

|

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Other topics |

Demographics

The exact numbers of Macedonian Muslims are not easy to establish. The historian Ivo Banac estimates that in the old Kingdom of Yugoslavia, before World War II, the Macedonian Muslim population stood at around 27,000.[11] Subsequent censuses have produced dramatically varying figures: 1,591 in 1953, 3,002 in 1961, 1,248 in 1971 and 39,355 in 1981. Commentators have suggested that the latter figure includes many who previously identified themselves as Turks. Meanwhile, the Association of Macedonian Muslims has claimed that since World War II more than 70,000 Macedonian Muslims have been assimilated by other Muslim groups, most notably the Albanians[12] (see Albanization). It can be estimated that the Macedonian Muslim population in North Macedonia in the year 2013 is 40.000 people.

Language and ethnic affiliation

Like their Christian ethnic kin, Macedonian Muslims speak the Macedonian language as their first language. Despite their common language and racial heritage, it is almost unheard of for Macedonian Muslims to intermarry with Macedonian Orthodox Christians. Macedonian ethnologists do not consider the Muslim Macedonians a separate ethnic group from the Christian Macedonians, but instead a religious minority within the Macedonian ethnic community. Intermarriage with the country's other Muslim groups (Bosniaks, Albanians and Turks) are much more accepted, given the bonds of a common religion and history.

When the Socialist Republic of Macedonia was established in 1944, the Yugoslav government encouraged the Macedonian Muslims to adopt an ethnic Macedonian identity. This has since led to some tensions with the Macedonian Christian community over the widespread association between Macedonian national identity and adherence to the Macedonian Orthodox Church.[13]

Political activities

The principal outlet for Macedonian Muslim political activities has been the Association of Macedonian Muslims. It was established in 1970 with the support of the authorities, probably as a means of keeping Macedonian Muslim aspirations in control.[14]

The fear of assimilation into the Albanian Muslim community has been a significant factor in Macedonian Muslim politics, amplified by the tendency of some Macedonian Muslims to vote for Albanian candidates. In 1990, the chairman of the Macedonian Muslims organization, Riza Memedovski, sent an open letter to the Chairman of the Party for Democratic Prosperity of Macedonia, accusing the party of using religion to promote the Albanisation of the Macedonian Muslims.[15] A controversy broke out in 1995 when the Albanian-dominated Meshihat or council of the Islamic community in North Macedonia declared that Albanian was the official language of Muslims in Macedonia. The decision prompted protests from the leaders and members of the Macedonian Muslim community.[13]

Occupation

Many Macedonian Muslims are involved in agriculture, and also work abroad. Macedonian Muslims are well known as fresco-painters, wood carvers and mosaic-makers. In the past few decades large numbers of Macedonian Muslims have emigrated to Western Europe and North America.

Gallery

Ottoman Bitola in the 1800s

Ottoman Bitola in the 1800s Prilep at the end of the 19th century

Prilep at the end of the 19th century Minarets in the Ottoman Skopje skyline

Minarets in the Ottoman Skopje skyline Ottoman Štip

Ottoman Štip

See also

- Macedonians (ethnic group)

- Greek Muslims

- Muslim Bulgarians and Pomaks

- Gorani

- Islam in North Macedonia

References

- Hugh, Poulton (2000). Who Are the Macedonians?. Hurst & Company, London. p. 124. ISBN 9781850655343.

- Pettifer, James (1999). The new Macedonian Question. Macmillan Press Ltd. p. 115. ISBN 9780230535794.

- Kowan, J. (2000). Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference. London: Pluto Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-7453-1594-1.

- Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars, published by the Endowment Washington, D.C. 1914, p.28, 155, 288, 317, Лабаури, Дмитрий Олегович. Болгарское национальное движение в Македонии и Фракии в 1894-1908 гг: Идеология, программа, практика политической борьбы, София 2008, с. 184-186, Поп Антов, Христо. Спомени, Скопje 2006, с. 22-23, 28-29, Дедиjeр, Jевто, Нова Србија, Београд 1913, с. 229, Петров Гьорче, Материали по изучаванието на Македония, София 1896, с. 475 (Petrov, Giorche. Materials on the Study of Macedonia, Sofia, 1896, p. 475)

- Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe - Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE). Muslims of Macedonia. p. 2, 11

- Лабаури, Дмитрий Олегович. Болгарское национальное движение в Македонии и Фракии в 1894-1908 гг: Идеология, программа, практика политической борьбы, София 2008, с. 184, Кънчов, Васил. Македония. Етнография и статистика, с. 39-53 (Kanchov, Vasil. Macedonia — ethnography and statistics Sofia, 1900, p. 39-53),Leonhard Schultze Jena. «Makedonien, Landschafts- und Kulturbilder», Jena, G. Fischer, 1927

- Fikret Adanir, Die Makedonische Frage: Ihre Entstehung und Entwicklung bis 1908, Wiesbaden 1979 (in Bulgarian: Аданър, Фикрет. Македонският въпрос, София2002, с. 20)

- Skutsch, Carl (2013-11-07). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. ISBN 9781135193881.

- Andrew Rossos, Macedonia and the Macedonians: a history, Hoover Institution Press, 2008, ISBN 0817948813, p. 52.

- Hugh Poulton, Who are the Macedonians?, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1995, ISBN 1850652384, pp. 29-31.

- Banac, Ivo (1989). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-8014-9493-1.

- Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who Are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. p. 124.

- Duncan M. Perry, "The Republic of Macedonia: finding its way", in Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe, ed. Karen Dawisha, Bruce Parrott, p. 256. (Cambridge University Press, 1997)

- Hugh Poulton, "Changing Notions of National Identity among Muslims", in Muslim Identity and the Balkan States, ed. Hugh Poulton, Suha Taji-Farouki (C. Hurst & Co, 1997)

- http://www.greekhelsinki.gr/pdf/cedime-se-macedonia-muslims.PDF

External links

- Literature about the Islam and the Muslims on the Balkans and in Southeast Europe at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009) (in Bulgarian)

- Muslims of Macedonia