Music of Minnesota

The music of Minnesota began with the native rhythms and songs of Indigenous peoples, the first inhabitants of the lands which later became the U.S. state of Minnesota. Their relatives, the half-breed Métis fur-trading voyageurs, introduced the chansons of their French ancestors in the late eighteenth century. As the territory was opened up to white settlement in the 19th century, each group of immigrants brought with them the folk music of their European homelands. Celtic, German, Scandinavian, and Central and Eastern European song and dance remain part of the vernacular music of the state today.

| Music of the United States |

|---|

Ethnic music has influenced and developed into modern folk music, and American musical genres such as gospel music, blues and jazz also are part of the state's musical fabric. Musicians, such as the Andrews Sisters and Bob Dylan, often started in Minnesota but left the state for the cultural capitals of the east and west coasts, but in recent years the development of an active music industry in Minneapolis has encouraged local talent to produce and record at home. The city's most influential contributions to American popular music happened in the 1980s, when the city's music scene "expanded the state's cultural identity" and launched the careers of acclaimed performers like the multi-platinum soul singer Prince. The Replacements and Hüsker Dü set off the national alternative rock boom of the 1990s. In the 1990s and 2000s, the Twin Cities played a role in the national hip hop scene with artists such as Atmosphere and Brother Ali.

The Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra was founded in the early 1900s, and by the 1930s it had attained international stature in performance and recording. Since renamed the Minnesota Orchestra, it regained much of its former renown in the first decade of the 21st century. Classical music aficianados also enjoy and support the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, the only full-time chamber orchestra in the nation. Choral groups and community ensembles are located in many communities. The state's educational system provides comprehensive programs in music education. The nation's largest public radio network provides classical and other music programming regionally and to the nation, and independent public stations program a variety of college, folk, and new music.

History

The music of Minnesota has its roots with the music of Indigenous peoples of the area. Traditional arrangements are generally based around vocal, percussive and dance music; Dakota folk songs can be celebratory, martial or ceremonial.[1] Early European settlers (French and Métis voyageurs) brought French chansons, which they sang while traveling along their fur trade routes.[2] These songs were described by one visitor as "light, airy & graceful", and were often adapted to the rhythm of their paddles while canoeing.[3] Later European settlers also brought with them traditional folk and classical music, especially choral and Christian-themed music, opera, and varieties of ethnic folk music including Slavic and Scandinavian styles. Modern-day traditional dance music is based mostly around schottisches, polkas and waltzes with instrumentation including fiddle, mandola, accordion and banjo.[4]

The first singing school in Minnesota opened in St. Anthony (now part of Minneapolis) in 1851. The Plymouth Congregational Church of Minneapolis began a singing group in 1857, followed by the first such club for women only, the Lorelei Club (later the Ladies' Thursday Musical Chorus), in 1892.[1]

Thousands of Norwegians settled in Minnesota in the last half of the 19th and first quarter of the 20th century. Subcultures formed based around village of origin (bygde), and then formed organizations to maintain their home dialect and musical traditions. These organizations held annual meetings (stevne) which featured folk dancing, singing, fiddling and poetry.[5] In the late 1860s, male choirs with Norwegian and Swedish singers formed in cities and Lutheran colleges in Minnesota. These choirs sang a variety of popular and patriotic songs, hymns and folk tunes. In the 1880s, these choirs inspired the organization of singing societies that sponsored music festivals; in 1886, five singing clubs joined to become the Union of Scandinavian Singers,[6] and the Norwegian Singers Association of America has met biannually since 1910.[7]

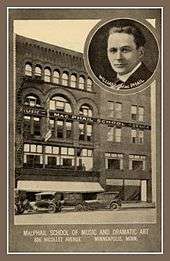

The end of the 19th century also saw the foundation of two long-running music groups, the Thursday Musical Chorus and the Apollo Men's Musical Group. Two of the most important Minnesota musical institutions were founded in the early 20th century, namely the MacPhail School of Violin (1907, later becoming the MacPhail Center for Music) and the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra (1903, later the Minnesota Orchestra).[1]

Minneapolis became a home for vaudeville comedy known as bondkomik (rustic humor), which featured multi-act plays, dances, songs and monologues.[8] Vaudeville shows usually ended with social dancing.[8] Minneapolis' most famous performers were the Norwegian-descended Eleonora and Ethel Olson and Ernest and Clarence Iverson (Slim Jim & the Vagabond Kid), and Swedish immigrant Hjalmar Peterson, whose company dominated the stage for two decades before the Great Depression.[6][8] General enthusiasm for Scandinavian musicals diminished in the face of intense propaganda and agitation toward foreign influence following the end of World War I, a process which was accelerated by the economic decline of the 1930s, and by the outbreak of World War II. Rural and regional dance music slowly died out, and became largely unknown.[5] During this era, however, the Leikarring movement (song-dances without instrumental accompaniment) began. Leikarring celebrated national Norwegian folk dance and song through musical societies like Minnesota's Norrona Leikarring.[7]

Education

Minnesotan law provides that public elementary and middle schools offer at least three and require at least two courses in the following four arts areas: dance, music, theater and visual arts. Public high schools must offer at least three and require at least one of the following five arts areas: dance, media arts, music, theater or visual arts.[10] Students may take music at the elementary and middle school ages, and many choose to take the subject as an elective in high school,[10] where schools often organize marching bands, choruses and other performance opportunities.[11] The Perpich Center for Arts Education is a school of choice which draws students from across the state, and has an extensive modern and classical music education program.[12]

The MacPhail Center for Music employs instructors from all over the world, who teach classes on 35 different instruments, the Suzuki method, and art therapy, to more than 7,200 students each year at 45 locations.[13][14]

Higher education in music is an important part of the programs at several of Minnesota's universities, including the University of Minnesota, which offers the Bachelor of Music degree in music education, therapy or performance, and graduate degrees in education, conducting and musicology.[15] The School of Music also offers masters and doctorate degrees.[16] The Duluth campus offers a Bachelor of Fine Arts in musical theatre.[17] McNally Smith College of Music, a college of contemporary music based in Saint Paul, offered Bachelor of Music degrees in music performance, recording technology, and music business, and Associates Degrees and diploma programs in recording technology[18] as well as the nation's first diploma in hip hop.[19] McNally Smith College of Music closed in December 2017 due to a lack of funds.[20]

Venues

Large venues for popular national music acts in Minnesota include the Target Center, Xcel Energy Center,[21] and US Bank Stadium. Northrop Auditorium on the University of Minnesota's main campus has a capacity of about 3,000, and hosts a variety of music and arts events.[22] Among these is the University of Minnesota Marching Band's annual indoor concert series, which have been performed at the venue since 1961.[23] The Armory and Roy Wilkins Auditorium also fill the need for mid-sized arenas at capacities of roughly 8,000 and 5,000 respectively.

Classical music is heard at Orchestra Hall in Minneapolis, a 2,500-seat auditorium "justly renowned for its rich, lively acoustics",[24] and St. Paul's 1,900-seat Ordway Center for the Performing Arts. Older traditional theaters seating about 2,000 include The Historic Orpheum Theatre, Pantages Theatre, and State Theatre, all in Minneapolis, and the Ordway Center for the Performing Arts in Saint Paul.[25][26] The Guthrie Theater holds over 1,000,[27] and The Cedar Cultural Center can seat 465.[28]

First Avenue, an influential music club in downtown Minneapolis, was opened as "The Depot" in 1970,[29][30][31] and went through several name changes until it became "First Avenue & 7th Street Entry" in 1980.[32] Its history of launching renowned acts such as Prince solidifies its importance in the current local scene and in Minnesota music history.[33][34] The owners of First Avenue also operate the Palace Theatre in St. Paul.

Mid-sized clubs also comprise a large part of the Twin Cities music scene. One popular club is the Myth Nightclub (Also referred to as Myth Live) in Maplewood, a suburb of St. Paul. Numerous bands/artists have performed there including Akon, All American Rejects, Fall Out Boy, Lifehouse, Maroon 5, and many more renowned bands. Others include the Cabooze and the Amsterdam Bar & Hall, all of which host all-ages shows as long as they meet local curfew laws (Although some may be listed as 15+ or 16+ for legal liability reasons involving hardcore dancing and other forms of moshing). A notable St. Paul venue that serves local musicians is Minnesota Music Cafe; opened in 1997 it continues to offer live music 7 days a week.[35]

Youth music venues, many of which operate as youth centers by day, include The Garage in Burnsville,[36] Depot Coffee House in Hopkins,[37] Enigma Teen Center in Shakopee,[38] and on some occasions the Apple Valley Teen Center.[39] Also, a few venues catering to crowds of all ages, now gone, are remembered as significant to the Twin Cities music scene. These include the Foxfire Coffee Lounge[40] in downtown Minneapolis and the Fireball Espresso Café[41] in Falcon Heights, St. Paul.

Other defunct but historically important venues include the Pence Opera House,[42] the Coffeehouse Extempore or Extemporé,[43] Jay's Longhorn Bar,[44] and the Uptown Bar.[45] The Prom Ballroom and Treasure Inn in Saint Paul and the Marigold Ballroom and the Flame Cafe[46] in Minneapolis featured prominent jazz, rock, country and other bands in the mid-20th century.[47][48]

Outside of the Twin Cities Metro Area important venues include the NorShor Theatre in Duluth,[49] Chisholm's Ironworld U.S.A. (renamed the Minnesota Discovery Center),[50] the Mayo Civic Center in Rochester, the Verizon Center in Mankato, and Ralph's Corner, for many years one of the premier indie rock clubs in the Fargo-Moorhead area.[51] These venues are often played by hard rock bands such as Halestorm[52] and Avenged Sevenfold that tend to draw more in "B-Markets".[53]

Radio

AMPERS is a state-wide association of independently-owned noncommercial stations that play music by local artists. These stations include KAXE, KBEM-FM, KFAI, KMOJ, KMSU, KMSK, KQAL, KSRQ, KUMD-FM, KUMM, KUOM (Radio K), KVSC and WTIP.[54]

Minnesota Public Radio's KCMP "The Current" also plays the music of Minnesota artists.

Recording studios and record stores

Minneapolis has been home to several important recording studios. The first studio in the state was Kay Bank, established by Amos Heilicher (who with his brother Daniel did "rack jobbing", jukebox distribution, and owned the Musicland chain[55]), Vern Bank, and studio engineer Bruce Swedien in 1955. The studio recorded hits from The Trashmen ("Surfin' Bird"), Dave Dudley ("Six Days on the Road"), The Underbeats, The Chancellors, The High Spirits, and The Castaways ("Liar, Liar" in 1965). Kay Bank helped popularize Soma Records and a distinctive style based on using three-track recording and echo effects.[56]

Herb Pilhofer and Tom Jung worked at Kay Bank before founding the world's first digital recording studio,[57] Sound 80 in 1969.[56] Sound 80 recorded numerous artists over the years, ranging from Bob Dylan's Blood on the Tracks to works from Dave Brubeck.[56] The studio now is the headquarters of Orfield Laboratories, whose anechoic chamber, is labeled the world's "quietest room" by the Guinness Book of World Records as of 2012.[58] Orfield lab also achieved the designation for their friends at Sound 80 as "the world's first digital recording studio" in the 2006 Guinness World Records. The two main studios are still fully intact, and they are filed for historic designation by the State and the Federal Government.

Other important studios in Minneapolis include the Dove studio,[56] which released several cult classic psychedelic and garage rock recordings in the 1960s, Blackberry Way,[56] founded by Paul Stark, who would later co-found the Twin/Tone record label. ESP Woody McBride's record label "Communique" and its subsidiaries "Sounds" and "Head in the Clouds" had released 100 records by 1998.[59]

Prince's Paisley Park Studios was used both by Prince and for outside music production by artists such as Madonna, Boy George, the Fine Young Cannibals and Paula Abdul.[60] The facility was also used for commercial production purposes like TV spots and movies, including 1993's Grumpy Old Men.[61] Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis founded Flyte Tyme on Nicollet Avenue in Minneapolis in 1985 and then moved to a 17,000-square-foot (1,600 m2) complex in Edina, Minnesota before relocating to Santa Monica, California in 2004.[56]

Flowers Studio in Minneapolis, founded in 1998 by the late Ed Ackerson, leader of the alternative rock bands Polara and the 27 Various, has hosted many notable musicians including the Jayhawks, The Replacements, Motion City Soundtrack, Golden Smog, and Soul Asylum.[62][63][64]

Pachyderm Recording Studio is a residential recording studio located in Cannon Falls within a secluded old-growth forest. The studio was founded in 1988 by Jim Nickel, Mark Walk and Eric S. Anderson, with acoustic design by Bret Theney of Westlake Audio. It boasts the same Neve 8068 recording console that was used in Jimi Hendrix's Electric Lady Studios as well as Studer tape machines. The house was designed by Herb Bloomberg, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Several other recording and production studios around Minnesota specialize in working with mainly independent artists like Carpet Booth Studios located in Rochester, MN. This specific studio finds its home in a renovated former, church building and hosts hundreds of musicians every year.

The Twin Cities are home to a few independent record stores, including Treehouse Records (previously known as "Oar Folkjokeopus" and "North Country Music"), the Electric Fetus (also in Duluth and Saint Cloud), Fifth Element, and Cheapo.[65] Let It Be Records, although its storefront has closed, still sells vinyl in occasional public sales and by mail order.[66][67] The now-defunct Northern Lights Music (and before it, Harpo's/Hot Licks) also carried many local and alternative artists during the 80s and 90s on Hennepin above 6th Street on Block E and at other metro locations in St. Paul's Midway, on White Bear Avenue (St. Paul) and Burnsville. The downtown Minneapolis Northern Lights store later moved to the former location of Music City, another retail music store, at 700 Hennepin.[68][69] The Midway Northern Lights location survives today as "Urban Lights" under different ownership and specializing in urban/funk/rap.

Genres

Classical, choral and opera

The Minnesota Orchestra was founded in 1903 as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. Although it was among the first to perform on the radio and to record,[70] it initially was not known as one of the country's great orchestras. In the 1930s, Eugene Ormandy transformed it into an excellent ensemble and expanded its repertory, making it the most-recorded orchestra in the United States, and giving it an international reputation.[71][72] Other illustrious conductors included Dimitri Mitropoulos and Antal Dorati.[73] Osmo Vänskä, a Finnish conductor, music director since 2003, took the orchestra into its second century. Its live performances and recordings in a program of the complete works of Ludwig van Beethoven have been received with enthusiasm,[74][75][76] the group has been called "brilliant",[77] and a critic has stated the musicians are enjoying "their first golden age" since the days of Ormandy and Mitropoulos.[78] Another critic wrote for The New Yorker of a concert in 2010 and its "uncanny, wrenching power, the kind you hear once or twice a decade" and thought that that day the Minnesota Orchestra was "the greatest orchestra in the world".[79] The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra is the only full-time professional chamber orchestra in the country,[80] and also tours and records. Professional orchestral ensembles outside the Twin Cities include the Duluth Superior Symphony Orchestra[81] and the Rochester Symphony Orchestra and Chorale.[82]

The Twin Cities' oldest major choral society is The Bach Society of Minnesota.[83] The New York Times International Datebook calls the Christmas performance of the St. Olaf College choir "one of the five significant global holiday events".[84] Extending choral work with VocalEssence, Philip Brunelle commissioned more than 100 works for chorus.[85]

For 42 years until 1986, the Metropolitan Opera was in residence at Northrop Auditorium during its spring tour.[86] Opera is now staged by the Minnesota Opera, co-founded as Center Opera by Dominick Argento in 1963, as part of the Walker Art Center.[87][88] With an early reputation as "progressive (and) 'alternative'",[88] the Minnesota Opera began to include traditional works in its repertory when it merged with Saint Paul Opera in 1975.[89]

The Minnesota Boychoir which is the oldest continuously operating Boys Choir in Minnesota and is currently under the leadership of Mark Johnson. The Boychoir has been involved with the Minnesota Orchestra, The Orpheum Theatre, The Zion dance company, as well as other regional and international tours.

Folk

Minnesota is home to many ethnic groups, who brought with them the folk music of their homelands. When these immigrants settled in rural farming areas, their communities retained Old World social and religious patterns that gave a context for music performance.[5] These ethnic communities frequently settled near each other, in Minnesota and in Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, North Dakota and South Dakota, and their musical and cultural identities blurred.[5] Norwegians and Swedes frequently lived near each other in Minnesota, and Swedish, Finnish and Norwegian music merged into Scandinavian music.[5] This music is perceived as a type of old-time music, which also developed from the area's German, Irish, English, Polish, Czech, and other Northern and Central European musics.[7]

Norwegian folk dance (bygdedanser) includes participatory social dances and dances performed for an audience like springar, gangar and halling.[91] The Norwegian gammeldans tradition, and those of other ancestries, continues in ethnic communities in Minnesota, where waltzes, schottisches or reinlander, and polkas are newer forms of old-time music.[8] Vocal music includes short poetic songs called stev, emigrant ballads which expressed nostalgia for Norway and express hope, despair and loss about life in the United States.[7] By the 1930s the Finnish epic Kalevala was still read and sometimes sung.[92]

For those whose social life centered on churches where music was prohibited by the Pietist and other movements, music was sometimes done at home or disguised as a game.[93] For others, secular, socialist and temperance halls became the community center where bands could include women.[94] Musical accompaniment includes the accordion, violin, guitar, bass guitar, piano, harmonica, organ, banjo and mandolin.[94] The Norwegian Hardanger fiddle or hardingfele tradition almost died out during the 1970s and then experienced a resurgence.[95]

Bob Dylan, a Duluth native, became the first major mainstream solo star from Minnesota in the 1960s, known for his unique lyricism and folk-rock style. He spent a brief period in Minneapolis during 1959–1961, attending the University of Minnesota, where he played shows at the Ten O'Clock Scholar on the West Bank of the University of Minnesota Minneapolis campus.[96] He was associated with Dinkytown, a bohemian area near the campus, where he listened to a wide variety of folk and blues.[96] As of 2007, Dylan maintained a home in Minnesota.[97] Bob Dylan the "King of Folk-Rock" had 5 #1 albums on the Billboard 200 from 1974 to 2009, including Planet Waves in '74.

The city's local folk scene produced a few well-known performers in the 1960s, besides Dylan who spent much of his early career based in New York, including the guitarist Leo Kottke and the trio Koerner, Ray & Glover.[96] Folk music continues to be a major part of the Minnesota music scene, and is broadcast by the Prairie Home Companion, a radio show hosted by author Garrison Keillor;[98] the Red House record label is the most influential local label for folk, and releases records by Ostroushko and Greg Brown, among others.[96] Boiled in Lead[96] who formed during the 1980s are still performing.[99]

Gospel

Minnesota is a creative center of the gospel music tradition. Robert Robinson, a musical treasure[100] who has been called "the Pavarotti of Gospel"[101] and whose voice has been called "too big for radio",[102] is the executive and artistic director of the Twin Cities Community Gospel Choir, which Minnesota Monthly said is the state’s most-decorated gospel group.[101]

Produced by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, the Sounds of Blackness won three Grammy Awards for their music and have performed three times for audiences of 1 billion: at the 1994 World Cup, the 1996 Summer Olympics and the 1998 World Figure Skating Championships.[103] Former Sounds of Blackness lead Ann Nesby has top-five hits on Billboard Hot Dance Club Songs charts and is the grandmother of American Idol finalist Paris Bennett.[103]

Blues

The blues tradition has been practiced in Minnesota for decades, notably by Lazy Bill Lucas and Percy Strother who lived and performed in Minneapolis.[104] Willie Murphy, who replaced Willie Walker in Willie & The Bees was named "one of the three charter members of the Minnesota Music Hall of Fame, along with Bob Dylan and Prince," according to Blues on Stage, who added, "the Minnesota Music Association has given more nominations and awards to Willie and his groups than anyone else".[105]

Other players gained loyal fans. Called "The Voice" by Tony Glover, Doug Maynard and his band backed Bonnie Raitt in 1982. Until he died at age 40, Maynard could "break a note into two and three parts simultaneously so that it sounded like he was harmonizing with himself".[106] Larry Hayes, formerly of the Lamont Cranston Band, wrote "Excusez Moi Mon Cheri" which The Blues Brothers recorded.[107] James Samuel "Cornbread" Harris, who collaborated with Augie Garcia and is the father of Jimmy Jam, is one of the area's senior players.[107][108]

Jazz

.jpg)

Jazz has been alive in the state since World War II when the Andrews Sisters from Minneapolis recorded the song "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy"[109] which Bette Midler covered decades later.[110] Local radio host Leigh Kamman covered jazz for more than sixty years, with vintage recordings and interviews with jazz artists.[111]

Pamela Espeland of MinnPost.com has chronicled many of the 3,500 live jazz performances in the Twin Cities during 2009.[112] Pianist Ethan Iverson and bassist Reid Anderson join Happy Apple drummer David King in The Bad Plus, who have performed during Christmas for ten years at the Dakota Jazz Club, a well-known local jazz venue.[113] Composer and pianist Carei Thomas recently celebrated his 70th birthday at the Walker Art Center.[114]

"No list of Minnesota music would be complete without mention of jazz great Jeanne Arland Peterson and her five children, Linda, Billy, Ricky, Patty, and Paul, as well as grandson Jason, who recently celebrated 22 years of performing their holiday shows." [115] Dave Koz said, "There is no family in the world quite like the Petersons. First of all, there's like 700 of 'em, and each one is more talented than the rest."[116]

Born, raised and residing in Minnesota, guitarist Reynold Philipsek performs gypsy jazz music as a solo artist, and with Minnesota gypsy jazz acts East Side, The Twin Cities Hot Club, and Sidewalk Café.[117]

Maria Schneider, born in Windom, is a composer and bandleader who studied music theory and composition at the University of Minnesota.

Other musicians that live and play in Minnesota:

Rhythm and blues

Minneapolis became noted as a center for rhythm and blues (R&B) in the 1980s, when the multi-talented star Prince (d. 2016) rose to fame. The city had little history in African American popular music, such as R&B, until Prince made his debut in 1978, eventually achieving five #1 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 with "When Doves Cry," "Let's Go Crazy," "Kiss," "Batdance" and "Cream." Prince also had eight #1 hits on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart from 1979 to 1991. He became the architect of the Minneapolis sound, a funk, rock and disco-influenced style of R&B, and inspired a legion of subsequent performers, including the Prince-related acts The Time, Wendy & Lisa and Vanity 6.[120] Curtiss A, who opened for Prince the first time Prince played First Avenue in 1980, at first thought that it was nice of Prince to let him open and then later realized: "You know: 'You guys think this is the top thing in town? Well, here: Minneapolis got a brand new bag.'"[33]

Prince fired Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis from The Time in 1983 because their production career began overtaking their roles in the band.[121] Their Flyte Tyme Productions began to gain national attention, and excelled at mainstream urban contemporary music, which had often been shunned by critics.[121] The pair's first mainstream breakthrough was Janet Jackson's Control in 1986,[122] which propelled her career and spawned numerous projects seeing the writing/production team work with artists as varied as Twin Cities acts Mint Condition,[123] Alexander O'Neal and Sounds of Blackness, to internationally-established acts Michael Jackson, New Edition, Boyz II Men, Patti LaBelle, and Human League.[121]

In 1980, Steven Greenberg and Cynthia Johnson, recording as Lipps Inc. at Sound 80, recorded "Funkytown,"[121] which reached #1 on both the U.S. and disco charts.[124][125] The song became a cultural touchstone; Homer Simpson of "The Simpsons" said the song moved him like few others,[126] and the song turned into the biggest seller in the history of the PolyGram label.[127] During the mid-1980s, eight children of the Wolfgramm family became The Jets, who enjoyed eight top 10 hits.[128] In 1998, Minneapolis R&B group Next had a #1 Hot 100 hit with "Too Close".

Rock

Rock and roll has a long history in the state. Garcia is remembered from the 1950s as the godfather of Minnesota rock 'n' roll.[129] Called by Billboard "one of the top 10 most consistent chartmakers ever", Bobby Vee, who had 38 songs in the Hot 100 charts, still tours with his sons, The Vees.[130] From the 1960s, a series of psychedelic and garage rock singles have become collector's items, including work of Mankato, Minnesota's The Gestures, The Litter's "Action Woman", "Faces" by T. C. Atlantic and Trip Thru Hell by the C. A. Quintet.[131] "Surfin' Bird" by The Trashmen reached #4 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1963,[132] "Liar, Liar" by The Castaways charted at number 12 in 1965, and the song "Evil Woman (Don’t Play Your Games With Me)" by the Minneapolis hard rock band Crow made the Billboard Top 20 in 1969.[133]

While attending the University of Minnesota in the late 1970s, Yanni played keyboards and synthesizers in several Twin Cities rock bands. He joined the band Chameleon in the early 1980s and enjoyed moderate regional commercial success before embarking on his solo new-age music career.[134]

Largely only known locally for new wave, The Suburbs were released under the local Twin/Tone Records label in 1978, and opened shows for Iggy Pop and The B-52's.[135] The Suicide Commandos helped to galvanize a punk, new-wave community based at first out of Jay's Longhorn Bar.[136]

Prior to the evolution of punk in the 1970s, there was little rock and roll tradition from Minneapolis, which author Steven Blush attributed to a lack of anything to "rebel against", noting that it was Minneapolis' friendly atmosphere that made future hardcore punk musicians "crazy and rebellious".[137] "Every A&R person in New York was present at CBs while The Replacements joyously flushed the set down the toilet, doing nothing but fractions of other people's songs," said Peter Jesperson who recorded them for Twin/Tone.[138]

In the mid-1970s, local musicians in the Minneapolis area began producing popular and innovative acts. Many signed to major record labels, and by the mid-1980s, some had achieved national prominence.[140] The first female rock bands, Vixen from Saint Paul went on to success in Los Angeles[141] and from Minneapolis, Têtes Noires released three albums.[142] The hardcore punk scene grew with The Replacements and Hüsker Dü, who started too early to profit from, but were pivotal in, the development of alternative rock.[143][144] The Replacements, who "might be the most legendary" Minnesota rock musicians,[145] eventually achieved some limited mainstream success, which led to member Paul Westerberg's solo career,[146] while Hüsker Dü started on local Reflex Records and became the first hardcore outfit to sign to a major label.[147] Soul Asylum was originally a Minneapolis hardcore band called Loud Fast Rules, who played with bands like Willful Neglect, Man Sized Action, Rifle Sport and Breaking Circus; they mixed funk and thrash metal with other influences.[148] The Twin Cities rock scene came to national prominence by 1984, when the Village Voice's critics poll, Pazz and Jop, named three Minneapolis recordings among the top ten of the year: Prince's Purple Rain, The Replacements' Let It Be, and Hüsker Dü's Zen Arcade.[140]

The late 1980s saw new sounds coming out of the state, when two singles from electronic band Information Society, "What's On Your Mind? (Pure Energy)" and "Walking Away", were MTV favorites.[135] The Jayhawks are a long-lived country-roots rock band who started in the mid-1980s.[149] Another group to form about the same time was Babes in Toyland, an early quasi-riot grrl band.[150] Many groups of the 1980s and 1990s eventually split up, and a number of other bands formed from the remnants. Bob Mould left Hüsker Dü after it imploded in 1988, to head Sugar and do solo projects.[151] Trip Shakespeare eventually transformed into Semisonic, who gained popularity in the late 1990s with the song "Closing Time".[152] Other prominent, recent rock acts from Minnesota include slowcore band Low and indie folk/bluegrass band Trampled by Turtles, both from Duluth,[153] experimental rock band Cloud Cult and indie rockers Tapes 'n Tapes, both from Minneapolis.[154] In the 2000s, Minnesota produced a number of acts such as Motion City Soundtrack, Owl City, Quietdrive, Sing It Loud and some metal and hardcore acts such as For All Those Sleeping, After the Burial, Write This Down and Four Letter Lie. Some of these acts like Motion City Soundtrack and Owl City went on to have minor mainstream success, Owl City gained a #1 Hot 100 hit with "Fireflies" in 2009. Emo pop-punk acts, such as Tiny Moving Parts, have been published in Alternative Press.

Hip hop

The Twin Cities region is home to a thriving underground hip hop scene,[155] due largely to the presence of Rhymesayers Entertainment.[156] Rhymesayers' artists, including Eyedea & Abilities, Brother Ali, Los Nativos, Musab, and, most notably, Atmosphere,[157] began to receive national attention in the late 1990s.[59]

Heiruspecs won City Pages "Best Live Artist" in 2004,[158] and in the same year Doomtree won "Best Hip Hop Artist".[159] For the past several years, through 2008, the scene owed some of its success to the annual Twin Cities Celebration of Hip Hop sponsored by Yo! The Movement and the website D. U. Nation.[160][161] In 2014 Manny Phesto was given "Best MN Releases" title by Pitchfork Media[162] and was credited by XXL with getting Ghosface Killah and Action Bronson to agree on something. In 2019, Lizzo had a #1 Hot 100 hit with "Truth Hurts". "[163]

Electronic dance music

Two locally and internationally-recognized Minneapolis electronic dance music artists are Woody McBride and Freddy Fresh (who walks a line with hip hop).[164][165]

Music about Minnesota

Several composers and performers have featured the state in their works. Classical composer Ferde Grofe depicted Minnesota in his Mississippi Suite.[166] John Philip Sousa wrote "Foshay Tower-Washington Memorial March" for the dedication of the Foshay Tower in 1929.[167] Sonja Thompson recorded "Dan Patch Two-Step", and Vern Sutton, Charlie Maguire, Peter Ostroushko and Ann Reed have recorded songs celebrating the Minnesota State Fair.[168] Tom Waits released two songs about Minneapolis, "Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis" (Blue Valentine 1978) and "9th & Hennepin" (Rain Dogs 1985).[169] In 1987, The Silencers released A Letter from St. Paul.[170] In 1997, The Mountain Goats released a song entitled "Minnesota" on their album Full Force Galesburg.[171] Lucinda Williams recorded "Minneapolis" (World Without Tears 2003).[172] In 1975, Northern Light reached the Billboard charts when they released a song titled "Minnesota" that sang the praises of the state's natural beauty.[173][174] In 2012, Ben Kyle released a song titled "Minneapolis" that illustrates the close relationship between St. Paul and Minneapolis.[175]

Notes

- Minneapolis Public Library (2001). "A History of Minneapolis: Music". Hennepin County Library. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- Nute, pp. 105–55

- Mayer, pp. 159–60

- "Leroy Larson and the Scandinavian Music Ensemble". Music Outfitters. Archived from the original on 2010-01-02. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Levy, p. 866

- Levy, p. 871

- Levy, p. 867

- Levy, p. 869

- Abbe, Mary (January 10, 2008). "Music Box". Star Tribune. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Minnesota Standards for Arts Education" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Education. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "MMEA All-State Program Eligibility Policies & FAQ's". Minnesota Music Educators Association. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Russell, Scott (March 5, 2008). "Perpich High School for the Arts—A mecca for creative teens". Twin Cities Daily Planet. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Combs, Marianne (September 13, 2006). "MacPhail Center for Music breaks new ground". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- "History". MacPhail Center for Music. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- "Degree Programs". University of Minnesota: School of Music. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Graduate School Catalog: Music". Regents of the University of Minnesota. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- "BFA Musical Theatre". University of Minnesota, Duluth, Department of Theatre. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Jossi, Frank (December 26, 2009). "McNally Smith College of Music: A music mecca in St. Paul". Dolan Media Newswires. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Baenen, Jeff (November 25, 2009). "Students Get Schooled on Hip-Hop at Minn. College". Associated Press via ABC News. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "McNally Smith College of Music closing due to lack of funds". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- Shepherd, p. 252

- "2002 Capital Request: Northrop Memorial Auditorium". Regents of the University of Minnesota. 2002. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- "History & Traditions". College of Liberal Arts | University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- Millett, Larry (2007). AIA Guide to the Twin Cities: The Essential Source on the Architecture of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-87351-540-4.

- "Hennepin Theatre Trust Fact Sheet". Hennepin Theatre Trust. September 29, 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-06-16. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- "History". Ordway Center for the Performing Arts. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- "About Our Spaces". Guthrie Theater. Archived from the original on 2010-01-11. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- "Who We Are/Where We Are". The Cedar. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- Moley, Raymond; et al. (1986). "Newsweek, Vol. 107, Issues 18–26". Newsweek. p. 71. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- Minnesota Society of Architects (2005). "Architecture Minnesota". 31. Minnesota Society American Institute of Architects: 54. Retrieved January 7, 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Noran, pp. 15–16

- "First Avenue & 7th Street Entry Band Files". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Scholtes, Peter (September 3, 2003). "First Love". City Pages. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- "Minneapolis Music & Nightlife - Local Bars". Boulevards. Archived from the original on April 2, 2004. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- "Minnesota Music Cafe". Minnesota Music Cafe. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- "THE GARAGE Youth Center". City of Burnsville. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "What Is the Depot?". City of Hopkins. Archived from the original on 2010-01-30. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Enigma Teen Center". City of Shakopee. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Teen Center". City of Apple Valley. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Weivoda, Amy. "21st-Century Fox". City Pages. Archived from the original on April 26, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Carlson, Keri. "Fireball Espresso Café". The Minnesota Daily. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Blegen, p. 504

- Keller, p. 42

- Cost, J., Earles, A., Fritch, M., Hickey, M., Klinge, S., Miller, E., Olson, D., Rowland, H., Ryan, M., and Valania, J.: A Tale Of Twin Cities: Hüsker Dü, The Replacements And The Rise And Fall Of The ’80s Minneapolis Scene, Magnet, June 12, 2005.

- Riemenschneider, Chris (October 30, 2009). "Thanks, Uptown Bar, we had a blast". Star Tribune. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- Meyer, Jim (October 11, 1995). "A New Flame". City Pages. Archived from the original on February 26, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Greene, p. 153

- "Lost Twin Cities II - Age of Big Band". Twin Cities Public Television. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Stodghill, Mark (October 9, 2009). "NorShor Experience strip club gets its liquor license back". Duluth News Tribune. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- "Ironworld announces new name, logo and mission". Minnesota Discovery Center. Jun 10, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- Byron, p. 111. Byron calls Ironworld a "theme park of iron-ore mining and European immigrant cultures".

- "Halestorm Book 'Halloween Scream' Tour With Starset + New Years Day". Loudwire. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- Sonicbids. "How to Book a DIY Tour Like a Pro". Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- "Independent Public Radio: An AMPERS Network". IPR Radio. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- Keller, pp. 7–17

- Herbers, Tom (June 8, 2005). "Three Tracks, Echo, and a Bunch of Hungry Teenagers". City Pages. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Wurzer, Cathy (July 28, 2006). "The quietest place on earth". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Weber, Tom (April 3, 2012). "In Minneapolis, the world's quietest room". MPR News. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- Gilmer, Vickie (November 21, 1998). "Local Noise: Five New Twin-City Acts". Billboard. p. 20. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- Shapiro, Eben (February 28, 1990). "Prince's Studio Makes A Star of Hometown". The New York Times. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- "Filming Locations for Grumpy Old Men". IMDb. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- Riemenschneider, Chris (5 October 2019). "Minneapolis 'musical wizard' and Polara frontman Ed Ackerson dies at 54". Star Tribune. Minneapolis-St. Paul. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Hoenak, Dave (6 February 2013). "Ed Ackerson on Flowers Studio: We let stuff come to us". City Pages. Minneapolis. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Bruch, Michelle (18 May 2018). "Inside Flowers Studio, a landmark hiding in the heart of Uptown". Southwest Journal. Minneapolis. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Bream, Jon (November 21, 1998). "Minneapolis Vital Statistics". Billboard. pp. 24–26. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Swensson, Andrea (February 16, 2009). "Let It Be Records to hold another huge sale this weekend". City Pages. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- "Let It Be Records". Let It Be. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- Goodman, Fred (May 11, 1985). "Twin Cities Dealer Finds His Own Niche". Billboard. p. 22. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- "Coinmen You Know: Twin Cities". Billboard. September 21, 1959. p. 94. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- "Brief History". Minnesota Orchestra. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- Rodríguez-Peralta, pp. 2–4

- Hassen, Marjorie. "Eugene Ormandy: A Centennial Celebration". Otto E. Albrecht Music Library, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- Oestreich, James R. (May 25, 2001). "Finn to Direct Minnesota Orchestra". The New York Times. p. E–3. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- Oestreich, James R. (December 17, 2006). "A Most Audacious Dare Reverberates". The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- Tsioulcas, Anastasia (July 2, 2005). "Vanska Big On Beethoven". Billboard. p. 40. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- The first disc was released on the BIS label in 2005, covering the 4th and 5th symphonies. "About the MOA". Minnesota Orchestra. Archived from the original on August 23, 2006. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- Fisher, Neil (February 26, 2009). "Minnesota Orch/Vanska at the Barbican". The Times. London. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- Finch, Hilary (August 28, 2006). "Minnesota Orchestra/Vänskä". The Times. London. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- Ross, Alex (March 22, 2010). "Battle of the Bands". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- "SPCO Announces balanced budget for 2007-08 Season" (Press release). Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. December 17, 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-01-08. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- "Mission, Vision and History". Duluth Superior Symphony Orchestra. 2009. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- "Rochester Symphony Orchestra & Chorale". Rochester Symphony Orchestra & Chorale. Archived from the original on June 30, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- "The Bach Society of Minnesota: An Inventory of Their Records". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- "St. Olaf Christmas Festival". American Public Media. December 2009. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- "Philip Brunelle is new music champion". Minnesota Public Radio. September 25, 2007. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- "Northrop Memorial Auditorium". Saint Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- Waleson, Hiedi (March 7, 2009). "Recession Isn't Pulling the Strings". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Zietz & Lynn, p. 142

- Zietz & Lynn, p. 143

- Jones, Chris (October 1, 2006). "The Best Bar in America". Esquire. Hearst Communications. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- Levy, pp. 866, 869

- Levy, p. 873

- Levy, pp. 867, 871, 874

- Levy, p. 874

- Levy, p. 870

- Unterberger, pg. 326

- Keller, p. 58

- Unterberger, p. 327

- Connelly, Dan and Poole, Jim Ed (March 17, 2008). "Boiled In Lead performs in The Current studios". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved January 2, 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Keller, p. 21

- Lewis, Courtney (February 2007). "Hear His Voice". Minnesota Monthly. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- "Robert Robinson: Biography". Robert Robinson. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- Keller, pp. 21–23

- Anderson, Corey (May 31, 2005). "Blues Great Percy Strother Dies at Age 58". City Pages. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- Keller, p. 64

- Keller, pp. 67–68

- Keller, p. 66

- Riemenschneider, Chris (April 20, 2006). "Past is present for Cornbread Harris". Star Tribune. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- Recording Industry of America, National Endowment for the Arts (March 7, 2001). "Songs of the Century". CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- Brackett & Hoard, p. 554

- "Leigh Kamman 60th Anniversary". Minnesota Public Radio. May 2003. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- Espeland, Pamela (December 30, 2009). "The year in jazz: Highs and lows". MinnPost. Archived from the original on 2010-01-02. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- McPherson, Steve (December 21, 2009). "The Bad Plus celebrate 10th annual holiday shows at the Dakota". City Pages. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- "Gift Shop: A Tribute to Carei F. Thomas". Walker Art Center. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- "Peterson Family Announces Holiday Shows" (Press release). The Peterson Family. November 16, 2009. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Keller, p. 33

- Riemenschneider, Chris (October 20, 2005). "Reynold's 25th parallel". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- "Conversations on Improvisation: George Cartwright". Mn Artists. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- "Anthony Cox". Allaboutjazz.com. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- Unterberger, pp. 323–325

- Unterberger, p. 325

- "Introducing: 'Producers of the Year' Jimmy (Jam) Harris and Terry Lewis". Ebony. July 1987. p. 126.

- "Flyte Time". Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- Whitburn, p. 121

- Keller, pp. 80, 84

- Brewster, p. 268

- Keller, p. 79

- Keller, p. 35

- Keller, p. 7

- Keller, p. 31

- Unterberger, p. 318

- Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music. Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 1-904041-96-5.

- "Minnesota's Fifty Greatest Hits". CityPages.com. June 8, 2005. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Yanni; Rensin, David (2002). Yanni in Words. Miramax Books. ISBN 1-4013-5194-8.

- "A Brief History of the Bands and Artists". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Unterberger, p. 319

- Blush, p. 224; "Prior to Punk, Minneapolis provided little fodder for the music industry. No Rock & Roll tradition existed. Maybe there was nothing to rebel against. Life in friendly places tends to make kids crazy and rebellious. Thus, Mpls cultivated its own brand of alienation and self-loathing." (sic)

- Keller, p. 116

- Walsh, Jim (October 31, 2005). "Tetes Noires founder Polly Alexander dead at 47". City Pages. The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- "The Minneapolis Music Collection". Minnesota Historical Society. 2002. Retrieved January 20, 2010. Purple Rain was at #2, Let It Be was at #4 and Zen Arcade at #8.

- "Vixen". Rita van Poorten (metalmaidens.com). Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- Walter, Kate (Nov–Dec 1987). "Têtes Noires: Clay Foot Gods (Rounder)". SPIN. 3 (7). Spin Media via Google Books. p. 32.

- Unterberger, p. 317

- Azerrad, p. 5

- Keller, p. 115

- Unterberger, pp. 319–320

- Blush, pp. 224, 226

- Blush, p. 224

- Unterberger, p. 322

- Unterberger, p. 323

- "Bob Mould". Trouser Press. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- "Semisonic". MTV Networks. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Sprague, David (April 1, 1995). "Vernon Yard/Virgin Is Counting On Low's 'Long Division'". Billboard. p. 14. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Menze, Jill (July 29, 2006). "Tapes N' Tapes Finds XL The Right Size". Billboard. p. 47. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Boller, Jay (March 26, 2009). "Sound Verité via Best of Twin Cities music blogs". The Minnesota Daily. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- Isa, Marisa (November 13, 2009). "NYC loves Twin Cities Hip-Hop: Session 1". Star Tribune. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- "Artists". Rhymesayers Entertainment. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- "Best Live Artist". City Pages. 2004. Archived from the original on February 26, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- "Best Hip Hop Artist". City Pages. 2004. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- Siasoco, Witt (August 20, 2008). "Yo! the Movement's 7th Annual Celebration of Hip Hop". Walker Art Center. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- Scholtes, Peter S. (August 19, 2008). "Yo! the Movement 7th Annual Celebration of Hip Hop". City Pages. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- Thompson, Paul (12/10/2014)"Minnesota Weird: The Best MN Hip-Hop Releases of 2014". Pitchfork.

- Thompson, Paul "Minneapolis Rapper Gets Action Bronson and Ghostface Killah To Agree on One Thing" (08/17/15) XXL Magazine

- Peloquin, Jahna (27 January 2014). "Local DJs Recall Playing Daft Punk's 1st U.S. Show in SPIN Article". Vita.MN. StarTribune. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Welch, Chris (10 November 2009). "They're rapping for a hip hop diploma". CNN.com. CNN. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "Around the World in 80 Minutes". West Valley Symphony – Utah. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- Douglas, pp. 236–238

- "Songs of the State and the Fair". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- "Blue Valentine". Amazon. ASIN B001EUMOP4. and "Rain Dogs". Amazon. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- The Silencers (1990). "A Letter from St. Paul". Amazon. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Darnielle, John (1997). ""Full Force Galesburg"". Amazon. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- Williams, Lucinda (2003). "World Without Tears". Amazon. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- Keller, p. 123

- "Northern Light-Minnesota video". NME. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- "Ben Kyle". Apple. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

References

- Azerrad, Michael (2002). Our Band Could Be Your Life. Back Bay Books. ISBN 0-316-78753-1.

- Blegen, Theodore Christian (1975). Minnesota: A History of the State (2nd ed.). University of Minnesota Press. p. 504. ISBN 0-8166-0754-0.

- Blush, Steven (2001). American Hardcore: A Tribal History. Feral House. ISBN 0-922915-71-7.

- Brackett, Nathan & Hoard, Christian (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Brewster, Bill (2000). Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3688-5.

- Byron, Janet (1996). Country Music Lover's Guide to the U.S.A. (1st ed.). St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-14300-1.

- Clarke, Gerald (2001). Get Happy: The Life of Judy Garland. Delta. ISBN 0-385-33515-6.

- Douglas, George H. (2004). Skyscrapers: A Social History Of The Very Tall Building In America. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2030-8.

- Keller, Martin (2007). Music Legends: A Rewind on the Minnesota Music Scene. D Media. ISBN 978-0-9787956-1-0.

- Levy, Mark; Rahkonen, Carl; and Haas, Ain in Koskoff, Ellen (ed.) (2001). "Scandinavian and Baltic Music". Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume Three: The United States and Canada. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-6040-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Greene, Victor R. (1992). A passion for polka: old-time ethnic music in America. University of California Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-520-07584-6.

- Mayer, Frank Blackwell (1986) [1932]. With Pen and Paper on the Frontier in 1851: The Diary and Sketches of Frank Blackwell Mayer. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-195-6.

- Mitchell, Jack W. (2005). Listener Supported: The Culture and History of Public Radio. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-98352-8.

- Noran, Rebecca (2000). First Avenue & 7th St Entry. First Avenue & 7th St. Entry. OCLC 47521819.

- Nute, Grace Lee (1955) [1931]. The Voyageur. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-012-7.

- Rodríguez-Peralta, Phyllis W. (2006). Philadelphia Maestros: Ormandy, Muti, Sawallisch. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-59213-487-4.

- Unterberger, Richie (1999). Music USA: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides. ISBN 1-85828-421-X.

- Shepherd, John; Horn, David & Laing, Dave (2003). Continuum encyclopedia of popular music of the world. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7436-5.

- Whitburn, Joel (2000). Top RandB Albums 1965-1998. Record Research. ISBN 0-89820-134-9.

- Zietz, Karyl Lynn & Lynn, Karyl Charna (1995). Opera companies and houses of the United States. McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-955-X.

External links

- Minnewiki: The Minnesota Music Encyclopedia – Wiki operated by Minnesota Public Radio

- Andersen, Jeanne. "Twin Cities Music Highlights". Jeanne Andersen's Timelines. Archived from the original on 2009-12-27. Retrieved January 2, 2010.