Mousehold Heath

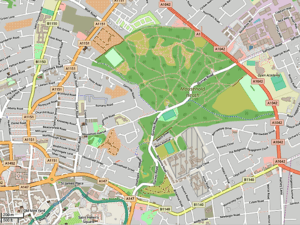

Mousehold Heath is a freely accessible area of heathland and woodland which lies to the north-east of the medieval city boundary of Norwich, in eastern England.

The name also refers to the much larger area of open heath that once extended from Norwich almost to the Broads, and which was kept free of trees by both human activity and the action of animals grazing on saplings. This landscape was transformed by enclosure during the nineteenth century and has now largely disappeared, as almost all of it has since been converted into farmland or landscaped parks, reverted to woodland, or has been absorbed by the rapid expansion of Norwich and its surrounding villages, where new roads, shops, houses and light industrial units have been built. The present Mousehold Heath consists of mostly broad-leaf woodland, with isolated areas of heath that are actively managed. It is home to a number of rare insects, birds and other vertebrates.

A chapel dedicated to William of Norwich (a local child who was murdered in 1114) was erected on the heath, of which little remains today. In 1549, Robert Kett camped on the heath with his followers, days before their uprising was suppressed by the authorities. The heath was in the past used by the local population to collect fuel, food and housing materials, as well as to extract sand, clay and gravel. Parts of it have previously been used as a cavalry training ground, a race course, a United States Army Air Forces base, an aerodrome and a prisoner-of-war camp. Nowadays the last remnant of the original Mousehold Heath, managed by Norwich City Council, is surrounded on all sides by housing and light industry.

Geology

Mousehold Heath is a 184-acre (74 ha) public area of heathland, woodland and recreational open space to be found to the north of Norwich city centre. It is the largest of the nature reserves managed by Norwich City Council. It was once an area of heathland that extended to the north and east of Norwich, which has since been largely converted to woods and farmland, or lost to housing development.[1]

The landscape of Mousehold Heath (as it was before enclosure occurred at the beginning of the nineteenth century) is part of an outwash plain created by fluvial processes. The geology of the area is complex, consisting of a set of vertical layers of glacial deposits from the Anglian Stage resting on a bedrock of Cretaceous chalk and the Norwich Crag Formation.[2]

Chalk was deposited 75 million years ago, when the area was part of a warm, tropical sea. The chalk is now exposed near the southern tip of the heath at St James' Pit, which is an 8.6-acre (3.5 ha) geological Site of Special Scientific Interest[3][4] and Geological Conservation Review site.[5] About two million years ago sands, gravels, quartz pebbles and clays were deposited across the area of Norfolk that now includes the heath. Similar materials were deposited during a glacial period that occurred more than 475,000 years ago. Clay, sand and gravel was laid over Mousehold Heath about 425,000 years ago, caused by the movement of melted ice. The heath's present landscape was more recently formed as a result of erosion, caused by streams cutting through the soft rocks. It later became altered when silts were blown over the topsoil, when the ground churned as a result of temperature variations and when sludge layers moved downhill during warmer seasons.[6]

Detailed information about the geological history of the present Mousehold Heath, in the form of a ‘Heritage Trail’ leaflet and accompanying notes for points around the trail, has been produced by Norwich City Council.[7]

Etymology

Various ideas have been proposed for the origin of the heath's name. The old name Mushold is nowadays interpreted as meaning 'mouse wood':[8] it was in the past thought the heath took its name from the Anglo-Saxon moch-holt ('thick wood'). John Stacy, writing in 1819, quoted earlier sources that derived the name from Moss-wold ('mossy hill') or - in his opinion, more probably - Monks-hold ('possessed by the monks').[9]

History

Medieval times

Extensive areas of heathland developed across Norfolk towards the end of the prehistoric period. It largely reverted to woodland again after the end of the Roman occupation, reappearing as heath as the population increased. According to the Domesday Book, the original area of Mousehold Heath was still substantially wooded, but the landscape changed as more trees were felled for fuel, and it eventually became largely treeless. This landscape was maintained by animal grazing and human activity, with parts of it being ploughed into fields, known as 'brecks'. The name Mousehold originally referred to the ‘holt’ or wood that existed before it became an area of heathland.[10]

St. Leonard's Priory was founded on the heath close to the city boundary in around 1094, as a temporary home for the monks of the unfinished Norwich Cathedral, and as a way of establishing Norman control over a nearby chapel. The priory was demolished in 1538 and nothing of it now survives above ground.[11]

In 1144 the body of a young apprentice boy called William was found on a part of the heath known at that time as Thorpe Wood. A false story was circulated that his death was the result of a 'ritual murder' carried out by local Jews. This was the first example in Europe of what became known as blood libel.[12] The sheriff of Norwich succeeded in protecting the innocent Jewish population from persecution in the wake of an angry reaction from the local people. The boy later attained the status of saint and martyr, and a chapel, originally dedicated to St. Catherine, was built where William's body was supposed to have been found. In 1168 it was rededicated as the chapel of St William in the Wood, and offerings continued to be made there until 1506. The overgrown remains of the site can be found on the northern edge of the present heath.[13][14]

In 1381 the final battle of the Peasants' Revolt took place a few days after a huge meeting of people on the heath occurred on 17 June. There Geoffrey Litster, later to be defeated at the Battle of North Walsham, was proclaimed "King of the Commons".[15]

1500-1810

.jpg)

In the Tudor period the heath was a continuously open countryside from Norwich to the edge of the Broads that was almost treeless.[1] The local population was free to collect wood from the heath, and to allow their stock to graze there.[16] Small villages bordered the heath: the parish of Salhouse, which was agrarian in nature, was typical of them. It consisted of a small settlement situated within a landscape of well-drained heath on slightly higher land, a mixture of woodland, marsh, arable land, and meadows on lower ground. Nearby ancient placenames such as Mouseholdheath Farm, Mousehold Cottage and Mousehold Farm, are an indicator of the proximity of the heath to Salhouse at that time.[17]

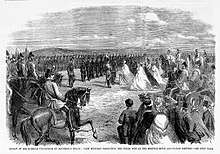

Kett's Rebellion began on 12 July 1549, during a period that became known as the 'commotion time'.[18] Led by Robert Kett (a local landowner and tanner) and his brother, it grew from a protest about enclosures into a full-scale insurgency. It culminated in the capture of the city of Norwich (then the largest English city outside London) and the surrounding countryside, with the rebels holding control of the city for over a month, basing themselves at a camp on Mousehold Heath and establishing other camps around Norfolk. After unsuccessfully petitioning the authorities for fairer treatment, they were able to defeat an attempt to oust them by the Marquis of Northampton, but a much larger government army, led by John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, succeeded in regaining control of Norwich and forcing them to abandon their camp. Six weeks after the start of the uprising, the rebellion was crushed by Warwick's forces in a decisive engagement, with perhaps three thousand insurgents being killed. There is some uncertainty about the exact site of the battle, said to have occurred at 'Dussindale'.[19]

Enclosure

.jpg)

Until the start of 19th century, Mousehold Heath still stretched to Woodbastwick, as can be see on Faden's 1797 map of Norfolk. A wide-open space crossed over with numerous paths and lanes, the heath dominated the countryside east of Norwich, and was entirely accessible to the local population. Self-interested landowners and city officials considered such an extensive area of uncultivated land as a prime target for development. As early as 1783 it was suggested that part of the heath near the city be made into a burial ground (an idea that was abandoned) and in 1792 there was a proposal to transform a large part of the heath into "pleasurable grounds". Those landowners whose large country houses were located around the borders of the heath pressed for the area to become enclosed. Rackheath’s common land was the first to be lost to enclosure in 1799, when Rackheath Park was enlarged.[20]

The entire heath was turned over to arable land and pasture by Parliamentary Enclosure Acts between 1799 and 1810, a process that produced long straight roads and new farms. There was little sympathy shown for the practical needs of the local population, many of whom became impoverished as they were increasingly denied access to the land. Parks surrounding large houses, such as at Sprowston, Rackheath, Thorpe St. Andrew and Little Plumstead, became enlarged by the acquisition of land, and new views were created for their owners by the removal of existing woodland and the planting of new belts of trees.[20]

1810–1914

.jpg)

Mousehold Heath was famously painted by a number of artists from the Norwich School of painters, including John Crome and John Sell Cotman,[21] as well as other painters such as John Constable. They found heathland landscapes intriguing and depicted them on a regular basis, despite the views of agriculturalists, who considered such landscapes to be valueless wasteland.[22] The Norwich school's depictions of Mousehold Heath lack human activity, animals or growing crops. The remoteness of Norfolk meant that few artists from outside the county could attempt to represent the heath. Many artists at the time preferred to depict what was considered to be the ideal form of landscape: lush, harmonious farming countryside containing pictorial devices such as woodland, which contrasted directly with the remote, barren environment of a heath such as Mousehold. The Norwich School witnessed the destruction of the heath following its enclosure, and their paintings of the heath would have brought back memories of a lost landscape.[23]

In his autobiographical work Lavengro, George Borrow recorded his meetings with gypsies on the heath.[24] The Norwich-born novelist and one-time Lord Mayor R. H. Mottram also valued the open space of Mousehold Heath. He once described it as "the property of those who have the privilege of Norwich birth".[25]

Public horse racing near Norwich first took place in 1838 and within a few years meetings were being held on a racecourse on Mousehold Heath.[26]

Before the 20th century the heath was used to extract sand and gravel. Victorian Ordnance Survey maps of the area show that there were lime kilns, marl pits and brick kilns, in addition to numerous extensive gravel pits, across the unenclosed part of the heath to the north-east of the city. The remains of the diggings can be found today.[27][28]

During much of the nineteenth century, the people of Pockthorpe, situated between Norwich's defensive walls and the heath, were relatively free from the control of local factory employers, being able to use Mousehold to graze their animals, and to collect food, fuel and raw materials for brick-making. The population of weavers, shop-keepers and labourers (as well as smugglers) was largely left to its own management, as local magistrates and the officials of Norwich Cathedral were more involved in city affairs. The people of Pockthorpe even parodied the authorities, for instance in electing their own ‘mayor’, and founding the Pockthorpe Guild in 1772. In 1844, in an attempt to preserve their traditional life, they began a campaign to establish full control over Mousehold Heath, for instance in forcing outsiders to accept a charge for taking materials off the land and making them use Pockthorpe men to do work on the heath. The Guild provided a number of benefits for the poor, but discriminated against people living in neighbouring communities.[29] The twenty-five year-long campaign failed, even when for a period it was supported by members of Norwich's political class. The local population then resorted to behaving badly towards the newly-created park, tearing notice boards, fighting and gambling in public, and consorting with the local regiment.[30]

The ownership of the remaining heathland was transferred to the city authorities in 1880, when the Church of England donated the land to the Corporation of Norwich, on the assurance that it prevented "the continuance of trespasses nuisances and unlawful acts" and held the heath "for the advantage of lawful recreation". The Pockthorpe committee was defeated, and the people of Pockthorpe, now forced to obey restrictive byelaws, could no longer use any part of the heath to support themselves. As a result of this change in the use of the land, the unmanaged part of heath remained ungrazed and it reverted to woodland.[31]

Despite strong local resistance, the 1884 Mousehold Heath Confirmation Act confirmed a local law establishing a number of ‘conservators’ to manage the transformation of the remaining part of the heath.[32][1] The current managers are Norwich City Council and the Mousehold Heath Conservators.[33]

The Britannia Barracks were built for the Norfolk Regiment on Mousehold Heath. After the Battle of Almansa in 1707, the regiment had been awarded the honour of wearing a figure of Britannia on their uniforms, and the new infantry barracks was named from the figure worn by the regiment. The main buildings were built between 1887 and 1897. The regiment left the barracks in 1959 when it amalgamated with the Suffolk Regiment to become the 1st East Anglian Regiment and moved to Bury St Edmunds. Most of the buildings subsequently became part of Norwich Prison.[34]

During the Second World War, a prisoner-of-war camp for German workers was established close to the old airport. Its exact location has yet to be verified.[35]

On 12 February 1942, the pilot of a Hampden bomber returning to RAF North Luffenham was killed when the aircraft crashed-landed on Mousehold Heath whilst attempting to reach Horsham St Faith, and on 25 July that year a Bristol Beaufort crashed on the heath, killing the crew of four.[36][37]

Mousehold Heath airfield

In October 1914 an old cavalry training drill ground on the heath was taken over by the Royal Flying Corps and converted into an aerodrome. It was used by several local firms in connection with aircraft production, including Boulton & Paul. Boulton & Paul employed up to 3000 people in assembling aircraft in Norwich, many of whom were women brought in to supplement the workforce. The women were trained in basic engineering skills in a specially provided training school. From October 1915, when the first aircraft was completed, over 2,500 machines were built by the company.[38]

In 1918 the Norwich Electric Tramways service from the city centre to Mousehold Heath was extended from Gurney Road to enable equipment and materials to run between Norwich railway station and the aerodrome.[39][40] The Norfolk & Norwich Aero Club was formed at Mousehold in 1927. From 1933 until the onset of the Second World War the aerodrome was the first Norwich Airport, with four grass landing strips.[41][42]

The airfield continued to be used until around 1950. Much of the old aerodrome was then built over when the Heartsease housing estate was created, but some of the airfield buildings survived and are now within the Roundtree Way industrial estate.[43]

The heath in recent years

Today there are numerous tracks and paths all over the remaining 184 acres (74 ha) of Mousehold Heath. There are two football pitches, a pitch and putt course, a restaurant, a bandstand and several parking areas. Various events are held there, including concerts, guided walks, conservation initiatives, football matches and fundraising events.[44] A single road, Gurney Road, passes through the middle of the heath. The original Ranger's house has been bought for renovation and restoration.

Vinegar Pond,[45] which was created by quarrying and subsequent wartime activity, is an important site for breeding frogs. It is fed by rain water and so has a tendency to dry out when the weather is hot.[46] 1946 aerial photographs of the area show the pond existed at this time, but it does not feature on earlier large-scale maps.[47][48]

In 1984 a new Mousehold Heath Act became law. In 1992 the bandstand by the football ground was rebuilt by the Mousehold Defenders using locally raised funds.[49]

The 67 acres (27 ha) Harrison's Wood, which was once originally part of the heath before it was enclosed and turned into a tree plantation, was opened to the public in May 2016. It lies within the White House Farm housing development.[50]

At the start of 2019 a draft version of the new Mousehold Heath Management Plan was made available online for public consultation. The Management Plan aimed to increase the safety and security of Mousehold Heath, increase the cleanliness of the heath and to safeguard the historic aspects and buildings of the heath among other aims.[51][52]

On 22 April 2019, a body was found in the heath. After investigation, the body was identified as that of Mark Sewell, 37, who had committed suicide by hanging.[53][54]

Wildlife

Mousehold Heath is a designated Local Nature Reserve[55][56] and County Wildlife Site.[57]

In recent years conservation management work has begun to restore the condition of the existing heathland and restore areas lost to woodland and scrub, so preserving a large number of scarce species present on the heathland. As grazing livestock cannot be used to remove encroaching woodland and so restore Mousehold's heathland areas, the Mousehold Heath Wardens, volunteers and contractors clear the woodland. Humus is removed so that heather species (Calluna vulgaris and Erica cinerea) can re-establish themselves from seed. Gorse, broom and saplings are removed and volunteers systematically ‘bruise’ the bracken with sticks, to reduce growth in future years.[58]

A variety of different vertebrates live on Mousehold Heath. Amphibians include the common frog and the common toad, while reptiles include the grass snake, the common lizard and the slowworm. Mammals on the heath include muntjac and roe deer, red fox, rabbits and various small rodents. As well as most common urban birds, the heath holds breeding sparrowhawks and tawny owls, as well as nuthatches, treecreepers and great spotted woodpeckers.

The heath is rich in invertebrates and is home to a number of rare butterflies, bees and other insects. Recorded species include the ruby-tailed wasp, digger wasp, Green Hairstreak butterfly, mottled grasshopper and tiger green beetle.[59]

Heathland plants to be found on Mousehold Heath include Sheep's Sorrel,[60] bracken, Wavy Hair-grass,[61] Mossy Stonecrop, Trailing St John's-wort, Common Cudweed and Viper's Bugloss.[59]

Footnotes

- "About Mousehold Heath". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Mousehold Heath Earth Heritage leaflet" (PDF). Norwich City Council and partners. p. 2. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Designated Sites View: St James' Pit". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- "Map of St James' Pit". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- "St James's Pit, Norwich (Jurassic - Cretaceous Reptilia)". Geological Conservation Review. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Origins of Mousehold Heath landscape" (PDF). Norwich City Council. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Mousehold Heath Earth Heritage Trail". Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- "Mousehold Heath". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Stacy, The city and county of Norwich, p. 74.

- Barnes and Williamson, Rethinking Ancient Woodland: The Archaeology and History of Woods in Norfolk.

- "Site of St Leonard's Priory, Norwich". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- The origin of the medieval accusation of 'ritual murder' known as blood libel and how it originated in Norwich is discussed in E.M.Rose's book The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe.

- "Remains of the chapel of St.William in the Wood". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Rose, E. M., The Murder of William of Norwich, p. 13.

- Walsingham, Thomas, (Editors Taylor, J., Childs, W. R., Watkiss, L.), The St Albans Chronicle: The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham Volume I 1376–1394 ISBN 0-19-820471-X

- Rawcliffe and Wilson, Medieval Norwich, pp. 292–3.

- Colin McCormick, The Book of Salhouse & Woodbastwick, p. 55.

- Rawcliffe and Wilson (eds.), Medieval Norwich, p. 285.

- "Introduction to Reconstructing Rebellion: Digital Terrain Analysis of the Battle of Dussindale (1549)". Internet Archaeology. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- Spooner, Sarah, Regions and Designed Landscapes in Georgian England, pp. 88–92.

- Paintings and etchings of the heath produced by members of the Norwich School are held by many different museums, including the British Museum.

- Waites, Ian, Common Land in English Painting 1700-1850, p. 65.

- "Mousehold Heath as a Location". Sam Smiles (ed.), In Focus: Mousehold Heath, Norwich c.1818–20 by John Crome, Tate Research Publication, 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Lavengro, by George Borrow". Project Gutenberg. p. 560. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Grimmer, Dan (12 May 2011). "Norwich memorial badly damaged in attack". Eastern Daily Press. Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Rawcliffe, Carole, Norwich Since 1550, p. 442.

- Norfolk LXIII.SE (includes: Norwich; Thorpe Next Norwich; Trowse with Newton.) (Map). Six Inches to One Mile. Cartography by the Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland. 1886. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Norfolk LXIII.NE (includes: Catton; Norwich; Spixworth; Sprowston.) (Map). Six Inches to One Mile. Cartography by the Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland. 1886. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Banks, Stephen, Informal Justice in England and Wales, pp. 160–2.

- Rawcliffe and Wilson, Norwich since 1550, p. 352.

- Meeres, Frank, A History of Norwich, p. 172.

- Banks, Stephen, Informal Justice in England and Wales, p. 163.

- "Management Plan - Mousehold Heath" (PDF). Norwich City Council and Mousehold Heath Conservators. p. 3. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Royle, Trevor. "Britain's Lost Regiments". Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Roger J. C. Thomas. "Prisoner of War Camps 1939-48" (PDF). English Heritage. p. 38. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "12.02.1942 No. 144 Squadron Hampden - AE141 PL-J Sgt. Nightingale D.F.M." Aircraft Remembered. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "The Crash of 1942". flickr. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- Rawcliffe and Wilson, Norwich since 1550, pp. 401–2.

- "Norwich Electric Tramway". George Plunkett's Photographs. Retrieved 3 May 2016. (see References below).

- "Mousehold - Tramway". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "Mousehold Heath Aerodrome". Norfolk Airfields. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- "Mousehold Heath Airfield". Pastscape. Historic England. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Record Details for Site of Mousehold Heath Aerodrome and World War Two heavy anti-aircraft battery". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Norfolk Historic Environment Service. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "About Mousehold Heath". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- The Ordnance Survey grid reference for Vinegar Pond is TG2409310495.

- "Mousehold Heath Earth Heritage Trail - Vinegar Road Gravel Pits". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Historic Map Explorer". Norfolk County Council. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Map Images". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Norwich Parks and Gardens". George Plunkett's Photographs. Retrieved 7 May 2018. (see References below).

- "New woodland near Sprowston is opened to the public". Eastern Daily Press. Archant Community Media Ltd. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- "Mousehold Heath Management Plan Review". Norwich City Council. 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Mousehold Heath Management Plan Summary 2019-2028 (PDF), Norwich City Council, retrieved 6 August 2019

- Grimmer, Dan (22 April 2019). "Body found at Mousehold Heath in Norwich". Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Ali, Taz (29 April 2019). "Man found dead at Mousehold Heath in Norwich is named". Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Mousehold LNR". Natural England. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "Map of Mousehold Heath". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "County Wildlife Sites". Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service (NBIS). Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "Volunteering in Norwich". The Conservation Volunteers. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Mousehold Heath Earth Heritage Trail (leaflet 12)". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "Mousehold Heath Earth Heritage Trail (leaflet 1)". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "Mousehold Heath Earth Heritage Trail (leaflet 11)". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

References

- Banks, Stephen (2014). Informal Justice in England and Wales, 1760-1914: The Courts of Public Opinion. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978 1 84383 940 8.

- Barnes, Gerry; Williamson, Tom (2015). Rethinking Ancient Woodland: The Archaeology and History of Woods in Norfolk. University of Hertfordshire Press. ISBN 978-1-909291-58-4.

- Funnell, B. M. (1975). "The Origin of Mousehold Heath, Norwich". Transactions of the Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists' Society. 23 (part 5): 251.

- Gunn, Peter (2017). Aviation Landmarks in Norfolk and Suffolk. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978 0 7509 8655 7.

- McCormick, Coiln (2016). The Book of Salhouse & Woodbastwick. Wellington, Somerset: Halgrove. ISBN 978 0 85704 292 7.

- Meeres, Frank (1998). A History of Norwich. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 1-86077-083-5.

- Plunkett, George A.F. (2007). Plunkett's Pictures of Norwich and Norfolk. Norfolk: Grey's Publishing. ISBN 9780955323416. The photographs and text from this book can be found at http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk.

- Rawcliffe, Carole; Wilson, Richard, eds. (2004). Medieval Norwich. London and New York: Hambleton and London. ISBN 1 85285 449 9.

- Rawcliffe, Carole; Wilson, Richard, eds. (2004). Norwich since 1550. London and New York: Hambleton and London. ISBN 1 85285 450 2.

- Rose, E. M. (2015). The murder of William of Norwich: The origins of the blood libel in medieval Europe. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978 0 19 021962 8.

- Spooner, Sarah (2016). Regions and Designed Landscapes in Georgian England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-85281-5.

- Stacy, John (1819). A topographical and historical account of the city and county of Norwich. London: Longman and others.

- Waites, Ian (2012). Common Land in English Painting 1700-1850. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-761-9.

External links

- Mousehold Heath Earth Heritage Trail

- Information from Norwich City Council about Mousehold Heath and the Mousehold Heath Conservators committee

- Mousehold Heath Conservators Draft annual report 2013 to 2014

- The Mousehold Heath Defenders' website

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mousehold Heath. |

- The 1585 map of Mousehold Heath from George Plunkett's Norwich Maps

- The archaeology of Mousehold Heath from Norfolk Heritage Explorer (showing the archaeological sites, historic buildings and former extent of the heath)

- Magic (UK Government website providing geographical information about Great Britain), centred on St. James Pit, Mousehold

- Mousehold Aerodrome silent Pathé News newsreel (1927), filmed at Mousehold Aerodrome

- Dragonflies on Mousehold Heath

- "Tales of Mousehold Heath". The Norwich Magazine. 1: 147–53, 178–82, 212–18, 247–52, 309–14. 1835.

- Drone flight over Mousehold Heath (YouTube)