Lavengro

Lavengro: The Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest (1851) is a work by George Borrow, falling somewhere between the genres of memoir and novel, which has long been considered a classic of 19th-century English literature. According to the author lav-engro is a Romany word meaning "word master".[1] The historian G. M. Trevelyan called it "a book that breathes the spirit of that period of strong and eccentric characters".[2]

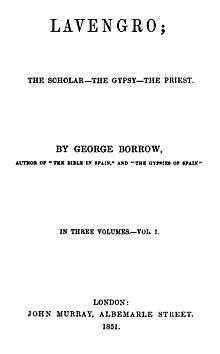

First edition title page | |

| Author | George Borrow |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiographical novel |

| Publisher | John Murray |

Publication date | 1851 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Followed by | The Romany Rye |

Its protagonist, whose name is George, is born the son of an officer in a militia regiment and is brought up in various barrack towns in England, Scotland and Ireland. After serving an apprenticeship to a lawyer he moves to London and becomes a Grub Street hack, an occupation which gives him ample opportunities to observe London low-life. Finally he takes to the road as a tinker. At various points through the book he associates with Romany travellers, of whom he gives memorable and generally sympathetic pen-portraits. Lavengro was followed by a sequel, The Romany Rye. However, neither of the two books are self-contained. Rather, Lavengro ends abruptly with chapter 100, and carries on directly in The Romany Rye. Thus both need to be read together, in order.

Borrow began work on Lavengro in 1842 and had written most of it by the end of 1843, but progress was then interrupted by a tour of eastern Europe and by bouts of ill-health, physical and mental.[3] He certainly intended the book to be an autobiography when he first set to work, and while writing it he more than once called it his Life in letters to his publisher, John Murray. In 1848 Murray advertised it as a forthcoming work to be called Lavengro, an Autobiography.[4] However the version Borrow finally delivered had been reshaped into an autobiographical novel whose fictional episodes are inextricably intertwined with genuine memoir.[5] Only the "scholar" in the book's subtitle refers to Borrow.[6]

The first edition had a print-run of only 3000 copies; it was such a slow seller that no reprint was needed until 1872.[7] Nor was it a critical success, reviewers being annoyed by the mix of fact and fiction and finding the treatment of Romany life insufficiently quaint. Blackwood's Magazine brought in a typical verdict:

We looked for some new revelations on the subjects of fortune-telling, hocus-pocus, and glamour. Lavengro, with his three attributes like those of Vishnu, might possibly be the Grand Cazique, the supreme prince of the nation of tinkers! We have read the book, and we are disappointed. The performance bears no adequate relation to the promise…The adventures, though interesting in their way, neither bear the impress of the stamp of truth, nor are they so arranged as to make the work valuable, if we consider it in the light of fiction.[8]

After Borrow's death in 1881 Lavengro began to find a new audience and enthusiastic praise from critics. Theodore Watts, in an introduction to the 1893 edition, declared that "There are passages in Lavengro which are unsurpassed in the prose literature of England".[9] This edition started a run of reprints which produced one or more almost every year for 60 years. Lavengro was included in the Oxford University Press World's Classics series in 1904, and in Everyman's Library in 1906.[10]

Notes

- George Borrow Lavengro (London: John Murray, 1851) p. 108.

- George M. Trevelyan British History in the Nineteenth Century and After (1782–1919) (London: Longmans, Green, 1941) p. 171.

- Herbert Jenkins The Life of George Borrow (London: John Murray, 1912) p. 366

- Herbert Jenkins The Life of George Borrow (London: John Murray, 1912) pp. 366, 388

- Walter Starkie, in his introduction to the Everyman edition, says, "We should approach Lavengro-Romany Rye as we do James Joyce's autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man."

- "Should you imagine that these three form one, permit me to assure you that you are very much mistaken." (Author's Preface to the First Edition)

- George A. Stephen Borrow House Museum: A Brief Account of the Life of George Borrow and his Norwich Home, with a Bibliography (Norwich: Norwich Public Libraries Committee, 1927) p. 18; Herbert Jenkins The Life of George Borrow (London: John Murray, 1912) p. 390.

- Blackwood's Magazine vol. 69, p. 323.

- George Borrow Lavengro (London: Ward, Lock, Bowden, 1893) p. vii.

- Catalogue entry at Copac.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Full-text online editions

Criticism

- Review of Lavengro and The Romany Rye by Anthony Campbell