Miꞌkmaq

The Miꞌkmaq or Miꞌgmaq (also Micmac, Lnu, Miꞌkmaw or Miꞌgmaw; English: /ˈmɪɡmɑː/; Miꞌkmaq: [miːɡmax])[4][5][6] are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas now known as Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the northeastern region of Maine. They call their national territory Miꞌkmaꞌki (or Miꞌgmaꞌgi). The nation has a population of about 170,000 (including 18,044 members in the recently formed Qalipu First Nation in Newfoundland[7][8]), of whom nearly 11,000 speak Miꞌkmaq, an Eastern Algonquian language.[9][10] Once written in Miꞌkmaq hieroglyphic writing, it is now written using most letters of the Latin alphabet.

Lnu | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Grand Council Flag of the Miꞌkmaq Nation.[1] Although the flag is meant to be displayed hanging vertically as shown here, it is quite commonly flown horizontally, with the star near the upper hoist. | |

A Miꞌkmaq father and child at Tufts Cove, Nova Scotia, around 1871 | |

| Total population | |

| 168,480 (2016 census)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada, United States (Maine) | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 36,470 |

| Nova Scotia | 34,130 |

| Ontario | 32,095 |

| Quebec | 25,230 |

| New Brunswick | 18,525 |

| British Columbia | 6,410 |

| Prince Edward Island | 2,330 |

| Languages | |

| English, Miꞌkmaq, French | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (mostly Roman Catholic), Miꞌkmaq traditionalism and spirituality, others | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Algonquian people, Abenaki, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Acadians | |

.svg.png)

The Santé Mawiómi, or Grand Council, was the traditional senior level of government for the Miꞌkmaq people until Canada passed the Indian Act (1876) to require First Nations to establish representative elected governments. After implementation of the Indian Act, the Grand Council took on a more spiritual function. The Grand Council was made up of chiefs of the seven district councils of Miꞌkmaꞌki.[11][12]

In 2011, the Government of Canada announced recognition to a group in Newfoundland and Labrador called the Qalipu First Nation. The new band, which is landless, had accepted 25,000 applications to become part of the band by October 2012.[13] In total over 100,000 applications were sent in to join the Qalipu, equivalent of 1/5 of the province's population. Several Miꞌkmaq institutions, including the Grand Council, had argued that the Qalipu Mi'kmaq Band did not have legitimate aboriginal heritage and was accepting too many members.[14][15][16] In November 2019, all concerns about Mi'kmaq Legitimacy had been addressed, and the Qalipu First Nation has been accepted by the Mi'kmaq Grand Council as being part of the Mi'kmaq Nation. "Chief Mitchell added, “Our inclusion into the AFN, APC and acknowledgement by the Mi’kmaq Grand Council are important to us; it is part of our reconciliation as Mi’kmaq people. Friendships are being formed, and relationships are being established. It is a good time for the Qalipu First Nation.”[17]

Etymology

The ethnonym has traditionally been spelled Micmac in English. The people have used different spellings: Miꞌkmaq (singular Miꞌkmaw) in Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland; Miigmaq (Miigmao) in New Brunswick; Miꞌgmaq by the Listuguj Council in Quebec; and Mìgmaq (Mìgmaw) in some native literature.[18]

Until the 1980s, "Micmac" remained the most common spelling in English. Although still referred to, this spelling has fallen out of favour in recent years. Most scholarly publications now use the spelling Miꞌkmaq, as preferred by the people. The media have adopted this spelling practice,[19] acknowledging that the Miꞌkmaq consider the spelling Micmac as "colonially tainted".[18] The Miꞌkmaq prefer to use one of the three current Miꞌkmaq orthographies when writing the language.[20]

Lnu (the adjectival and singular noun, previously spelled "L'nu"; the plural is Lnúk, Lnuꞌk, Lnuꞌg, or Lnùg) is the term the Miꞌkmaq use for themselves, their autonym, meaning "human being" or "the people".[21]

Various explanations exist for the origin of the term Miꞌkmaq. The Miꞌkmaw Resource Guide says that "Miꞌkmaq" means "the family":

The definite article "the" suggests that "Miꞌkmaq" is the undeclined form indicated by the initial letter "m". When declined in the singular it reduces to the following forms: nikmaq - my family; kikmaq - your family; wikma - his/her family. The variant form Miꞌkmaw plays two grammatical roles: 1) It is the singular of Miꞌkmaq and 2) it is an adjective in circumstances where it precedes a noun (e.g., miꞌkmaw people, miꞌkmaw treaties, miꞌkmaw person, etc.)[22]

The Anishinaabe refer to the Miꞌkmaq as Miijimaa(g), meaning "The Brother(s)/Ally(ies)", with the use of the nX prefix m-, opposed to the use of n1 prefix n- (i.e. Niijimaa(g), "my brother(s)/comrade(s)") or the n3 prefix w- (i.e., Wiijimaa(g), "brother(s)/compatriot(s)/comrade(s)").[23]

Other hypotheses include the following:

The name "Micmac" was first recorded in a memoir by de La Chesnaye in 1676. Professor Ganong in a footnote to the word megamingo (earth), as used by Marc Lescarbot, remarked "that it is altogether probable that in this word lies the origin of the name Micmac." As suggested in this paper on the customs and beliefs of the Micmacs, it would seem that megumaagee the name used by the Micmacs, or the Megumawaach, as they called themselves, for their land, is from the words megwaak, "red", and magumegek, "on the earth", or, as Rand recorded, "red on the earth", megakumegek, "red ground", "red earth". The Micmacs may have thought of themselves as the Red Earth People, or the People of the Red Earth. Others seeking a meaning for the word Micmac have suggested that it is from nigumaach, my brother, my friend, a word that was also used as a term of endearment by a husband for his wife ... Still another explanation for the word Micmac suggested by Stansbury Hagar in "Micmac Magic and Medicine" is that the word megumawaach is from megumoowesoo, the name of the Micmacs' legendary master magicians, from whom the earliest Micmac wizards are said to have received their power.[24]

Members of the Miꞌkmaq historically referred to themselves as Lnu, but used the term níkmaq (my kin) as a greeting.[25] The French initially referred to the Miꞌkmaq as Souriquois[26] and later as Gaspesiens, or (transliterated through English) Mickmakis. The British originally referred to them as Tarrantines.[27]

History

Pre-contact culture

Archaeologist Dean Snow says that the fairly deep linguistic split between the Miꞌkmaq and the Eastern Algonquians to the southwest suggests the Miꞌkmaq developed an independent prehistoric cultural sequence in their territory. It emphasized maritime orientation, as the area had relatively few major river systems.[28] According to ethnologist T. J. Brasser, as the indigenous people lived in a climate unfavorable for agriculture, small semi-nomadic bands of a few patrilineally related families subsisted on fishing and hunting. Developed leadership did not extend beyond hunting parties.[29]

Food and hunting

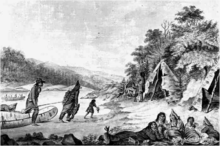

The Miꞌkmaq lived in an annual cycle of seasonal movement between living in dispersed interior winter camps and larger coastal communities during the summer. The spawning runs of March began their movement to converge on smelt spawning streams. They next harvested spawning herring, gathered waterfowl eggs, and hunted geese. By May, the seashore offered abundant cod and shellfish, and coastal breezes brought relief from the biting black flies, stouts, midges and mosquitoes of the interior. Autumn frost killed the biting insects during the September harvest of spawning American eels. Smaller groups would disperse into the interior where they hunted moose and caribou.[30] The most important animal hunted by the Miꞌkmaq was the moose, which was used in every part: the meat for food, the skin for clothing, tendons and sinew for cordage, and bones for carving and tools. Other animals hunted/trapped included deer, caribou, bear, rabbit, beaver and porcupine.[31]

Bear teeth and claws were used as decoration in regalia. The women also used porcupine quills to create decorative beadwork on clothing, moccasins, and accessories. The weapon used most for hunting was the bow and arrow. The Miꞌkmaq made their bows from maple. They would store lobsters in the ground for later consumption. They ate fish of all kinds, such as salmon, sturgeon, lobster, squid, shellfish, and eels, as well as seabirds and their eggs. They hunted marine mammals: porpoises, whales, walrus, and seals.[31]

Hunting moose

Throughout the Maritimes, moose was the most important animal to the Miꞌkmaq. It was their second main source of meat, clothing and cordage, which were all crucial commodities. They usually hunted moose in groups of 3 to 5 men. Before the moose hunt, they would starve their dogs for two days to make them fierce in helping to finish off the moose. To kill the moose, they would injure it first, by using a bow and arrow or other weapons. After it was down, they would move in to finish it off with spears and their dogs. The guts would be fed to the dogs. During this whole process, the men would try to direct the moose in the direction of the camp, so that the women would not have to go as far to drag the moose back. A boy became a man in the eyes of the community after he had killed his first moose. It marked the passage after which he earned the right to marry. Once moose were introduced to the island of Newfoundland, the practice of hunting moose with dogs was used in the Bay of Islands region of the province.

First contacts

The Miꞌkmaq territory was the first portion of North America that Europeans exploited at length for resource extraction. Reports by John Cabot, Jacques Cartier, and Portuguese explorers about conditions there encouraged visits by Portuguese, Spanish, Basque, French, and English fishermen and whalers, beginning in the early years of the 16th century. Early European fishermen salted their catch at sea and sailed directly home with it. But they set up camps ashore as early as 1520 for dry-curing cod. During the second half of the century, dry curing became the preferred preservation method.[32]

These European fishing camps traded with Miꞌkmaq fishermen; and trading rapidly expanded to include furs. By 1578 some 350 European ships were operating around the Saint Lawrence estuary. Most were independent fishermen, but increasing numbers were exploring the fur trade.[33]

Trading furs for European trade goods changed Miꞌkmaq social perspectives. Desire for trade goods encouraged the men devoting a larger portion of the year away from the coast trapping in the interior. Trapping non-migratory animals, such as beaver, increased awareness of territoriality. Trader preferences for good harbors resulted in greater numbers of Miꞌkmaq gathering in fewer summer rendezvous locations. This in turn encouraged their establishing larger bands, led by the ablest trade negotiators.[34]

Geography

The Miꞌkmaq territory was divided into seven traditional districts. Each district had its own independent government and boundaries. The independent governments had a district chief and a council. The council members were band chiefs, elders, and other worthy community leaders. The district council was charged with performing all the duties of any independent and free government by enacting laws, justice, apportioning fishing and hunting grounds, making war and suing for peace.

The eight Miꞌkmaq districts (including Ktaqmkuk which is often not counted) are:

- Epekwitk aq Piktuk (Epegwitg aq Pigtug)

- Eskikewaꞌkik (Esgeꞌgewaꞌgi)

- Kespek (Gespeꞌgewaꞌgi)

- Kespukwitk (Gespugwitg)

- Siknikt (Signigtewaꞌgi)

- Sipekniꞌkatik (Sugapuneꞌgati)

- Ktaqmkuk (Gtaqamg)

- Unamaꞌkik (Unamaꞌgi)

Note : The orthography between parentheses is the one used in the Gespeꞌgewaꞌgi area.

In addition to the district councils, the Mꞌikmaq had a Grand Council or Santé Mawiómi. The Grand Council was composed of Keptinaq ("captains" in English), who were the district chiefs. There were also Elders, the Putús (Wampum belt readers and historians, who also dealt with the treaties with the non-natives and other Native tribes), the women's council, and the Grand Chief. The Grand Chief was a title given to one of the district chiefs, who was usually from the Miꞌkmaq district of Unamáki or Cape Breton Island. This title was hereditary within a clan and usually passed on to the Grand Chief's eldest son.

The Grand Council met on a little island on the Bras d'Or lake in Cape Breton called Mniku. Today the site is within the reserve called Chapel Island or Potlotek. To this day, the Grand Council still meets at Mniku to discuss current issues within the Miꞌkmaq Nation. Taqamkuk was defined as part of Unamaꞌkik historically and became a separate district at an unknown point in time. ...

Housing

The Miꞌkmaq lived in structures called wigwams. They cut down saplings, which were usually spruce, and curved them over a circle drawn on the ground. These saplings were lashed together at the top, and then covered with birch bark. The Miꞌkmaq had two different sizes of wigwams. The smaller size could hold 10-15 people and the larger size 15-20 people. Wigwams could be either conical or domed in shape.

On June 24, 1610, Grand Chief Membertou converted to Catholicism and was baptised. He concluded an alliance with the French Jesuits which affirmed the right of Miꞌkmaq to choose Catholicism and\or Miꞌkmaq tradition. The Miꞌkmaq, as trading allies with the French, were amenable to limited French settlement in their midst.

17th and 18th centuries

Colonial wars

In the wake of King Phillips War between English colonists and Native Americans in southern New England (which included the first military conflict between the Miꞌkmaq and New England), the Miꞌkmaq became members of the Wapnáki (Wabanaki Confederacy), an alliance with four other Algonquian-language nations: the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet.[35]The Wabanaki Confederacy were also allied with the Acadian people in Acadia.

Over a period of seventy-five years, during six wars in Miꞌkmaꞌki (Acadia and Nova Scotia), the Miꞌkmaq and Acadians fought to keep the British from taking over the region (See the four French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War). France lost military control of Acadia in 1710, and political claim (apart from Cape Breton) by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht with England. But the Míꞌkmaq were not included in the treaty and never conceded any land to the British.

In 1715, the Miꞌkmaq were told that the British now claimed their ancient territory by the Treaty of Utrecht, which the Miꞌkmaq were no party to. They formally complained to the French commander at Louisbourg about the French king transferring the sovereignty of their nation when he did not possess it. They were only then informed that the French had claimed legal possession of their country for a century, on account of laws decreed by kings in Europe, that no land could be legally owned by any non-Christian, and that such land was therefore freely available to any Christian prince who claimed it. Miꞌkmaw historian Daniel Paul observes that

If this warped law were ever to be accorded recognition by modern legalists they would have to take into consideration that, after Grand Chief Membertou and his family converted to Christianity in 1610, the land of the Miꞌkmaq had become exempt from being seized because the people were Christians. However, it's hard to imagine that a modern government would fall back and try to use such uncivilized garbage as justification for non-recognition of aboriginal title.[36]

Along with Acadians, the Miꞌkmaq used military force to resist the founding of British (Protestant) settlements by making numerous raids on Halifax, Dartmouth, Lawrencetown and Lunenburg. During the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War between France and Britain in Europe, the Miꞌkmaq assisted the Acadians in resisting the British during the Expulsion. The military resistance was reduced significantly with the French defeat at the Siege of Louisbourg (1758) in Cape Breton. In 1763, Great Britain formalized its colonial possession of all of Miꞌkmaki in the Treaty of Paris.

Treaties

The Míꞌkmaq signed a series of peace and friendship treaties with Great Britain. The first was after Father Rale's War (1725). In 1725 the British signed a treaty (or "agreement") with the Miꞌkmaq, but the rights of the Miꞌkmaq defined in it to hunt and fish on their lands have often been disputed by the authorities.[37][38]

The nation historically consisted of seven districts, which was later expanded to eight with the ceremonial addition of Great Britain at the time of the 1749 treaty.

Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope signed a Peace Treaty in 1752 on behalf of the Shubenacadie Miꞌkmaq.[39] With the signing of various treaties, the 75 years of regular warfare ended in 1761 with the Halifax Treaties. According to Historian Stephen Patterson, the British imposed the treaties on the Miꞌkmaq to confirm the British conquest of Miꞌkmaꞌki.[40]

According to historian John G. Reid, although the treaties of 1760-61 contain statements of Miꞌkmaw submission to the British crown, he believes that the Miꞌkmaw intended a friendly and reciprocal relationship. This assertion, Reid proposes, is based on what is known of the surrounding discussions, combined with the strong evidence of later Miꞌkmaw statements. Reid suggests that the Miꞌkmaw fighters negotiated the Treaties from a position of power (The census data indicates there were about 300 Miꞌkmaw fighters in the region compared to thousands of British soldiers). Reid asserts the Miꞌkmaw leaders who represented their people in the Halifax negotiations in 1760 had clear goals: to make peace, establish secure and well-regulated trade in commodities such as furs, and begin an ongoing friendship with the British crown. In return, Reid suggests they offered their own friendship and a tolerance of limited British settlement, although without any formal land surrender.[41] To fulfill the reciprocity intended by the Miꞌkmaq, Reid reports that any additional British settlement of land would have to be negotiated, and accompanied by giving presents to the Miꞌkmaq. (There was a long history of the French giving Miꞌkmaq people presents to be accommodated on their land, starting with the first colonial contact.) The documents summarizing the peace agreements failed to establish specific territorial limits on the expansion of British settlements, but assured the Miꞌkmaq of access to the natural resources that had long sustained them along the regions' coasts and in the woods. Their conceptions of land use were quite different. The Miꞌkmaq believed they could share the land, with the British growing crops, and their people hunting as usual and getting to the coast for seafood.[42]

The arrival of the New England Planters and United Empire Loyalists in greater number put pressure on land use and the treaties. This migration into the region created significant economic, environmental and cultural pressures on the Miꞌkmaq. The Miꞌkmaq tried to enforce the treaties through threat of force. At the beginning of the American Revolution, many Miꞌkmaq and Maliseet tribes supported the Americans against the British. They participated in the Maugerville Rebellion and the Battle of Fort Cumberland in 1776. (Míꞌkmaq delegates concluded the first international treaty, the Treaty of Watertown, with the United States soon after it declared its independence in July 1776. These delegates did not officially represent the Miꞌkmaq government, although many individual Miꞌkmaq did privately join the Continental army as a result.) In June 1779, Miꞌkmaq in the Miramichi valley of New Brunswick attacked and plundered some of the British in the area. The following month, British Captain Augustus Harvey, in command of HMS Viper, arrived and battled with the Miꞌkmaq. One Miꞌkmaq was killed and 16 were taken prisoner to Quebec. The prisoners were eventually taken to Halifax. They were released on 28 July 1779 after signing the Oath of Allegiance to the British Crown.[43][44][45]

As their military power waned in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Miꞌkmaq people made explicit appeals to the British to honour the treaties and reminded them of their duty to give "presents" to the Miꞌkmaq in order to occupy Miꞌkmaꞌki. In response, the British offered charity or, the word most often used by government officials, "relief". The British said the Miꞌkmaq must give up their way of life and begin to settle on farms. Also, they were told they had to send their children to British schools for education.[46]

The Treaties did not gain legal status until they were enshrined into Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982. Every October 1, "Treaty Day" is now celebrated by people in Nova Scotia.

Burials

During this time period two colonial figures were honoured at their deaths by the Miꞌkmaq. Two hundred Miꞌkmaq chanted their death song at the burial of Governor Michael Francklin.[47] They also celebrated the life of Pierre Maillard.[48]

American Revolution

During the American Revolution, some Miꞌkmaq supported the British while others did not. In 1780, they gave shelter to the 84th Regiment of Foot that had been shipwrecked off Cape Breton.[49]

19th century

Royal Acadian School

Walter Bromley was a British officer and reformer who established the Royal Acadian School and supported the Miꞌkmaq over the thirteen years he lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia (1813-1825).[51] Bromley devoted himself to the service of the Miꞌkmaq people.[52] The Miꞌkmaq were among the poor of Halifax and in the rural communities. According to historian Judith Finguard, his contribution to give public exposure to the plight of the Miꞌkmaq "particularly contributes to his historical significance". Finguard writes:

Bromley's attitudes towards the Indians were singularly enlightened for his day. ... Bromley totally dismissed the idea that native people were naturally inferior and set out to encourage their material improvement through settlement and agriculture, their talents through education, and their pride through his own study of their languages.[51]

MicMac Missionary Society

Silas Tertius Rand in 1849 help found the Micmac Missionary Society, a full-time Miꞌkmaq mission. Basing his work in Hantsport, Nova Scotia, where he lived from 1853 until his death in 1889, he travelled widely among Miꞌkmaq communities, spreading the Christian faith, learning the language, and recording examples of the Miꞌkmaq oral tradition. Rand produced scriptural translations in Miꞌkmaq and Maliseet, compiled a Miꞌkmaq dictionary and collected numerous legends, and through his published work, was the first to introduce the stories of Glooscap to the wider world. The mission was dissolved in 1870. After a long period of disagreement with the Baptist church, he eventually returned to the church in 1885.

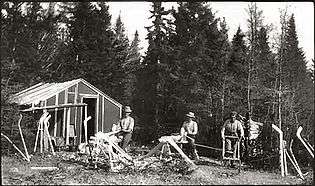

Mic-Mac hockey sticks

The Miꞌkmaq practice of playing hockey appeared in recorded colonial histories from as early as the 18th century. Since the nineteenth century, the Miꞌkmaq were credited with inventing the ice hockey stick.[53] The oldest known hockey stick was made between 1852 and 1856. Recently, it was appraised at $4 million US and sold for $2.2 million US. The stick was carved by Miꞌkmaq from Nova Scotia, who made it from hornbeam, also known as ironwood.[54]

In 1863, the Starr Manufacturing Company in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia began to sell the Mic-Mac hockey sticks nationally and internationally.[55] Hockey became a popular sport in Canada in the 1890s.[56] Throughout the first decade of the twentieth century, the Mic-Mac Hockey Stick was the best-selling hockey stick in Canada. By 1903, apart from farming, the principal occupation of the Miꞌkmaq on reserves throughout Nova Scotia, and particularly on the Shubenacadie, Indian Brook and Millbrook Reserves, was producing the Mic-Mac Hockey Stick.[55] The department of Indian Affairs for Nova Scotia noted in 1927, that the Miꞌkmaq remained the "experts" at making hockey sticks.[57] The Miꞌkmaq continued to make hockey sticks until the 1930s, when the product was industrialized.[58]

20th and 21st centuries

Jerry Lonecloud (1854–1930) worked with historian and archivist Harry Piers to document the ethnography of the Miꞌkmaq people in the early 20th century. Lonecloud wrote the first Miꞌkmaq memoir, which his biographer entitled "Tracking Dr. Lonecloud: Showman to Legend Keeper".[59] Historian Ruth Holmes Whitehead wrote, "Ethnographer of the Micmac nation could rightly have been his epitaph, his final honour."[60]

World Wars

In 1914, over 150 Miꞌkmaq men signed up during World War I. During the First World War, thirty-four out of sixty-four male Miꞌkmaq from Lennox Island First Nation, Prince Edward Island enlisted in the armed forces, distinguishing themselves particularly in the Battle of Amiens.[61] In 1939, over 250 Miꞌkmaq volunteered in World War II. (In 1950, over 60 Miꞌkmaq enlisted to serve in the Korean War.)

Treaty Day

Gabriel Sylliboy was the first Miꞌkmaq elected as Grand Chief (1919) and the first to fight for treaty recognition - specifically, the Treaty of 1752 - in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia (1929).

In 1986, the first Treaty Day was celebrated by Nova Scotians on October 1 in recognition of the Treaties signed between the British Empire and the Miꞌkmaq people. The first treaty was signed in 1725 after Father Rale's War. The final treaties of 1760-61, marked the end of 75 years of regular warfare between the Miꞌkmaq and the British (see the four French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War). The treaty-making process of 1760-61, ended with the Burying the Hatchet ceremony (1761).

The treaties were only formally recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada once they were enshrined in Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982. The first Treaty Day occurred the year after the Supreme Court upheld the Peace Treaty of 1752 signed by Jean-Baptiste Cope and Governor Peregrine Hopson. Since that time there have been numerous judicial decisions that have upheld the other treaties in the Supreme Court, the most recognized being the Donald Marshall case.

Tripartite Forum

In 1997, the Miꞌkmaq–Nova Scotia–Canada Tripartite Forum was established.

On August 31, 2010, the governments of Canada and Nova Scotia signed a historic agreement with the Miꞌkmaq Nation, establishing a process whereby the federal government must consult with the Miꞌkmaq Grand Council before engaging in any activities or projects that affect the Miꞌkmaq in Nova Scotia. This covers most, if not all, actions these governments might take within that jurisdiction. This is the first such collaborative agreement in Canadian history including all the First Nations within an entire province.[62]

Miꞌkmaq Kinaꞌ matnewey

The Nova Scotia government and the Miꞌkmaq community have made the Miꞌkmaq Kinaꞌ matnewey, which is the most successful First Nation Education Program in Canada.[63][64] In 1982, the first Miꞌkmaq-operated school opened in Nova Scotia.[65] By 1997, all Miꞌkmaq on reserves were given the responsibility for their own education.[66] There are now 11 band-run schools in Nova Scotia.[67] Nova Scotia now has the highest rate of retention of aboriginal students in schools in the country.[67] More than half the teachers are Miꞌkmaq.[67] From 2011 to 2012 there was a 25% increase in Miꞌkmaq students going to university. Atlantic Canada has the highest rate of aboriginal students attending university in the country.[68][69]

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

In 2005, Nova Scotian Miꞌkmaq Nora Bernard led the largest class-action lawsuit in Canadian history, representing an estimated 79,000 survivors of the Canadian Indian residential school system. The Government of Canada settled the lawsuit for upwards of CA$5 billion.[70]

On June 11, 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper made an apology to the residential school survivors.[71]

In the fall of 2011, there was an Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission that travelled to various communities in Atlantic Canada, who were all served by the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. For 37 years (1930-1967), 10% of Miꞌkmaq children attended the institution.[72]

Miꞌkmaq of Newfoundland

Celebrations

In the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador, October is celebrated as Miꞌkmaq History Month. The entire Miꞌkmaq Nation celebrates Treaty Day annually on October 1. This was the date when the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1752 was signed by Jean-Baptiste Cope of Shubenacadie and the king's representative. It was stated that the natives would be given gifts annually," as long as they continued in Peace".[73]

Religion, spirituality, and tradition

Current forms of Miꞌkmaq faith

Some Miꞌkmaq people practice the Catholic faith, some only practice traditional Miꞌkmaq religion; but many have adopted both religions due to the compatibility between Christianity and traditional Miꞌkmaq faith.[74] Ethnologist Angela Robinson provides an in-depth study of both Traditionalist and Miꞌkmaw Catholic beliefs and practices in her monograph, Tán Teli-Ktlamsitasit (Ways of Believing): Míkmaw Religion in Eskasoni, 2005.

Oral traditions in Miꞌkmaq culture

The Miꞌkmaq people had very little in the way of physical recording and storytelling; petroglyphs, while used, are believed to have been extremely rare. In addition, it is not believed that pre-contact Miꞌkmaq had any form of written language. As such, almost all of Miꞌkmaq traditions were passed down orally, primarily via storytelling. There were traditionally three levels of oral traditions: religious myths, legends, and folklore.

- Myths are used to tell the stories of the earliest possible time, of things that are religiously and spiritually significant. This includes Miꞌkmaq creation stories, and myths which account for the organization of the world and society; for instance, how men and women were created and why they are different from one another. Myths are powerful symbolically and are the expression of how things came to be and should be. The most well known Miꞌkmaq myth is that of Glooscap.

- Legends are oral traditions related to particular places. Legends can involve the recent or distant past, but are most important in linking people and specific places in the land.

- Folktales are fictitious stories that involve all the people. These traditional tales are used to give moral or social lessons to youth, or are told for amusement about the way people are. Good storytellers are highly prized by the Miꞌkmaq,[75] as they provide important teachings that shape who a person grows to be, and they are sources of great entertainment. A good story was, and is, an experience often treasured by Miꞌkmaq children.

There is one myth explaining that the Miꞌkmaq once believed that evil and wickedness among men is what causes them to kill each other. This causes great sorrow to the creator-sun-god, who weeps tears that become rains sufficient to trigger a deluge. The people attempt to survive the flood by traveling in bark canoes, but only a single old man and woman survive to populate the earth.[76]

Spiritual sites

One spiritual capital of the Miꞌkmaq nation is Mniku, the gathering place of the Míkmaq Grand Council or Santé Mawiómi, Chapel Island in Bras d'Or Lake of Nova Scotia. The island is also the site of the St. Anne Mission, an important pilgrimage site for the Miꞌkmaq (Robinson 2005). The island has been declared a historic site.[77]

First Nation subdivisions

Miꞌkmaw names in the following table are spelled according to several orthographies. The Miꞌkmaw orthographies in use are Míkmaw pictographs, the orthography of Silas Tertius Rand, the Pacifique orthography, and the most recent Smith-Francis orthography. The latter has been adopted throughout Nova Scotia and in most Miꞌkmaw communities.

Demographics

| Year | Population | Verification |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 4,500 | Estimation |

| 1600 | 3,000 | Estimation |

| 1700 | 2,000 | Estimation |

| 1750 | 3,000[80] | Estimation |

| 1800 | 3,100 | Estimation |

| 1900 | 4,000 | Census |

| 1940 | 5,000 | Census |

| 1960 | 6,000 | Census |

| 1972 | 10,000 | Census |

| 1998 | 15,000 | SIL |

| 2006 | 20,000 | Census |

The pre-contact population is estimated at 3,000–30,000.[81] In 1616, Father Biard believed the Miꞌkmaq population to be in excess of 3,000, but he remarked that, because of European diseases, there had been large population losses during the 16th century. Smallpox and other endemic European infectious diseases, to which the Miꞌkmaq had no immunity, wars and alcoholism led to a further decline of the native population. It reached its lowest point in the middle of the 17th century. Then the numbers grew slightly again, before becoming apparently stable during the 19th century. During the 20th century, the population was on the rise again. The average growth from 1965 to 1970 was about 2.5%.

Commemorations

The Miꞌkmaq people have been commemorated in numerous ways, including HMCS Micmac (R10), and place names such as Lake Micmac, and the Mic Mac Mall.[82]

Notable Miꞌkmaq

Academics

- Pamela Palmater, professor at Ryerson University

- Patricia Doyle-Bedwell, professor at Dalhousie University

- Marie Battiste, professor at the University of Saskatchewan

Activists

- Anna Mae Aquash, activist (1946–1976)

- J. Kevin Barlow, health campaigner

- Nora Bernard, Canadian Indian residential school system activist

- Donald Marshall, Jr., wrongly convicted of murder

- Daniel N. Paul, Elder, author, tribal historian, columnist, and human rights activist

- Gabriel Sylliboy, Grand Chief of the Miꞌkmaq Nation, 1918 to 1964

Artists

- Rita Joe, poet

- Ursula Johnson, visual artist

- Phyllis Grant, film maker and artist

- Jessica Harmon, actress[83]

- Richard Harmon, actor[83]

Athletes

- Patti Catalano, marathon runner

- Sandy McCarthy, played for the Calgary Flames ice hockey team

- Everett Sanipass, played for the Quebec Nordiques ice hockey team

Military

- Étienne Bâtard (18th century)

- Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope

- Sam Gloade

- Paul Laurent[84]

Other

- Judge Timothy Gabriel, first Miꞌkmaq judge in Nova Scotia[85]

- Peter Paul Toney Babey, a Miꞌkmaq chief

- Indian Joe, a scout around the time of the American Revolutionary War

- Nikki Gould, actress, Degrassi: Next Class

- Noel Jeddore, Saqmaw forced into exile (1865–1944)[86]:5[87]:33[88]:163

- Noel Knockwood, Grand Council member and spiritual leader of the Miꞌkmaq people

- Jerry Lonecloud, entertainer, ethnographer and medicine man

- Henri Membertou, Grand Chief and spiritual leader (c.1525-1611)

- Lawrence Paul, a chief of Millbrook First Nation

- Peter Paul Toney Babey, medical practitioner in the 1850s

Maps

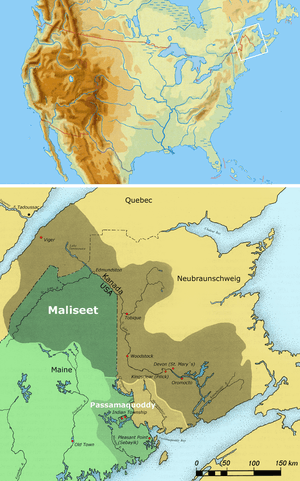

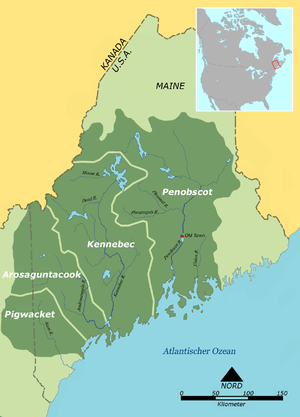

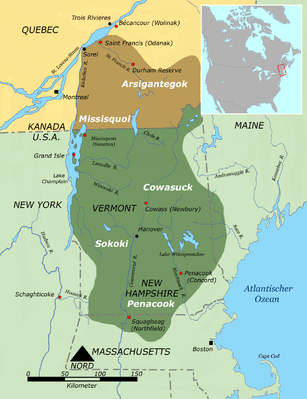

Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket) Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

See also

- Algonquian peoples

- List of Grand Chiefs

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Silas Tertius Rand

- Tarrantine

- Qalipu Miꞌkmaq First Nation Band

Notes

- "Flags of the World". Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- "Aboriginal Ancestry Responses (73)". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Government of Canada. 2017-10-25. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- Jeddore, John Nick (August 25, 2011). "There were no Indians here ..." TheIndependent.ca.

- "Native Languages of the Americas: Miꞌkmaq (Miꞌkmawiꞌsimk, Miꞌkmaw, Micmac, Míkmaq)". Native-Languages.org. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Lockerby, Earle (2004). "Ancient Miꞌkmaq Customs: A Shaman's Revelations" (PDF). The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. 24 (2): 403–423. see page 418, note 2

- Sock, S., & Paul-Gould, S. (2011). Best Practices and Challenges in Miꞌkmaq and Maliseet/Wolastoqi Language Immersion Programs.

- "Programs and Services". Qalipu.ca.

- "Thousands of Qalipu Miꞌkmaq applicants rejected again", CBC, Dec 08, 2017.

- "Table 1: Indigenous Languages Spoken in the United States (by Language)". YourDictionary.

- contenu, English name of the content author / Nom en anglais de l'auteur du. "English title / Titre en anglais". www12.statcan.ca.

- Julien, Donald M. (October 2007). Kekina'muek (learning)Learning about the Mi'kmaq of Nova Scotia (PDF). Eastern Woodland Print Communication. p. 11. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- "Mi'kmaq Historical Overview". Cape Breton University. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Qalipu Miꞌkmaq Membership Claims, CBC Canada, 04 October 2012

- Battiste, Jaimie. "Nova Scotia Chiefs Raise Concerns over Qalipu Miꞌkmaq Band" (PDF). mikmaqrights.com. Miꞌkmaq Rights Initiative. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- Grand Council of Micmacs (4 October 2013). "STATEMENT TO UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ANAYA" (PDF). Retrieved 4 January 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Battiste, Jaime. "Defining Aboriginal Identity: What the Courts Have Stated" (PDF). Mikmaqrights.com. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- "Search Results for "grand council" – Qalipu". Retrieved Jul 31, 2020.

- Emmanuel Metallic et al., 2005, The Metallic Mìgmaq-English Reference Dictionary

- Anne-Christine Hornborg, Miꞌkmaq Landscapes (2008), p. 3

- Paul (2000), p. 10: "It is now the preferred choice of our People."

- The Nova Scotia Museum's Míkmaq Portraits database

- Miꞌkmaw Resource Guide, Eastern Woodlands Publishing (1997)

- Weshki-ayaad, Lippert, Gambill (2009). Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary

- cited in Paul to Marion Robertson, Red Earth: Tales of the Micmac, with an introduction to their customs and beliefs (1965) p. 5.

- Johnston, A. J. B. (2013). Niꞌn na L'nu: The Miꞌkmaq of Prince Edward Island. Acorn Press. p. 96.

- Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France

- Lydia Affleck and Simon White. "Our Language". Native Traditions. Archived from the original on 2006-12-16. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- Snow, p.69

- Brasser, p.78

- Bock, pp.109&110

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-01-25. Retrieved 2007-01-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Brasser, pp.79&80

- Costain, Thomas B. (1954). The White and The Gold. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. p. 54.

- Brasser, pp.83&84

- The allied tribes occupied the territory which the French named Acadia. The tribes ranged from present-day northern and eastern New England in the United States to the Maritime Provinces of Canada. At the time of contact with the French (late 16th century), they were expanding from their maritime base westward along the Gaspé Peninsula /St. Lawrence River at the expense of Iroquoian-speaking tribes. The Miꞌkmaq name for this peninsula was Kespek (meaning "last-acquired").

- Paul (2000), pp. 74-75.

- Historian William Wicken notes that there is controversy about this assertion. While there are claims that Cope made the treaty on behalf of all the Miꞌkmaq, there is no written documentation to support this assertion (Wicken 2002, p. 184)

- Patterson, Stephen (2009). "Eighteenth-Century Treaties:The Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy Experience" (PDF). Native Studies Review. 18 (1).

- John Reid. Nova Scotia: A Pocket History, Fernwood Press. 2009. p. 23

- Plank, Unsettled Conquest, p. 163

- Upton, L.F.S. (1983). "Julien, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Sessional papers, Volume 5 By Canada. Parliament July 2 - September 22, 1779; Wilfred Brenton Kerr. The Maritime Provinces of British North America and the American Revolution], p. 96

- Among the annual festivals of the old times, now ylost, was the celebration of St. Aspinquid's Day; he was known as the Indian Saint. St. Aspinquid appeared in the Nova Scotia almanacks from 1774 to 1786. The festival was celebrated on or immediately after the last quarter of the moon in the month of May, when the tide was low. The townspeople assembled on the shore of the North West Arm and shared a dish of clam soup, the clams being collected on the spot at low water. There is a tradition that in 1786, soon after the American Revolutionary War, when there were threats of American invasion of Canada, agents of the US were trying to recruit supporters in Halifax. As people were celebrating St. Aspinquid with wine, they suddenly hauled down the Union Jack and replaced it with the Stars and Stripes [US flag]. This was soon reversed, but public officials quickly left, and St. Aspinquid was never after celebrated at Halifax. (See Akins. History of Halifax, p. 218, note 94)

- Reid. p. 26

- Nova Scotia Historical Society; Nova Scotia Historical Society. Report and collections. Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Halifax – via Internet Archive.

- "Burial celebration of Pierre Maillard", Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. 1, p. 44

- Clarke, James Stanier; Jones, Stephen; Jones, John (8 June 2019). "The Naval Chronicle". J. Gold – via Google Books.

- "Explore the Royal Collection Online". www.rct.uk.

- Fingard, Judith (1988). "Bromley, Walter". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. VII (1836–1850) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Nova Scotia Historical Society; Nova Scotia Historical Society. Report and collections. Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Halifax – via Internet Archive.

- Cutherbertson, Brian (2005). "The Starr Manufacturing Company: Skate Exporter to the World". Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. 8: 60.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Slingshot: Improving the Modern Hockey Stick". www.odec.ca.

- Cutherbertson (2005), p. 61.

- Cutherbertson (2005), p. 58.

- Cutherbertson (2005), p. 73.

- Cutherbertson (2005), p. 63.

- "New Book Features First Known Memoir of a Miꞌkmaq" (Press release). Nova Scotia Museum. October 11, 2002.

- Whitehead, Ruth Holmes (2005). "Lonecloud, Jerry". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XV (1921–1930) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Sark, John Joe (December 2013). "In our words, stories of Veterans". Miꞌkmaq Maliseet Nations News.

- "Miꞌkmaq of Nova Scotia, Province of Nova Scotia and Canada Sign Landmark Agreement" (Press release). Indian and Northern Affairs Canada and Government of Nova Scotia - Aboriginal Affairs. August 31, 2010 – via Market Wire.

- Benjamin, Chris (2014). Indian School Road: Legacies of the Shubenacadie Residential School. Nimbus. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-77108-213-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey". Retrieved Jul 31, 2020.

- Benjamin (2014), p. 208.

- Benjamin (2014), p. 210.

- Benjamin (2014), p. 211.

- Benjamin (2014), p. 214.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-26. Retrieved 2014-10-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Police investigate death at Bernard's home". Halifax Daily News. Archived from the original on 2008-10-26. Retrieved 2018-11-10 – via Arnold Pizzo McKiggan.

- Benjamin (2014), p. 190.

- Benjamin (2014), p. 195.

- Branch, Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Communications (3 November 2008). "Treaty Texts - 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty". www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca.

- (Robinson 2005)

- "Mi'kmaq Spirit Home Page". www.muiniskw.org.

- Canada's First Nations - Native Creation Myths Archived 2014-01-14 at the Wayback Machine, University of Calgary

- CBCnews. Cape Breton Míkmaq site recognized

- "Government of Canada Announces the Creation of the Qalipu First Nation Band' by Marketwire". Retrieved Jul 31, 2020.

- "Press Release September 26, 2011". Retrieved Jul 31, 2020.

- Massachusetts Historical Society; John Davis Batchelder Collection (Library of Congress) (8 June 1792). Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Boston : The Society – via Internet Archive.

- "Micmac". www.dickshovel.com.

- Bates, George T. (1961). Megumaage: the home of the Micmacs or the True Men. A map of Nova Scotia.

- Shetty, Seine. "If I Had Wings wraps production in Maple Ridge". PlayBack. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Laurent, Paul". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Sawler, Sarah (30 July 2013). "50 Things You Don't Know About Halifax - Halifax Magazine".

- Tulk, Jamie Esther (July 2008), "Our Strength is Ourselves: Identity, Status, and Cultural Revitalization among the Miꞌkmaq in Newfoundland" (PDF), Memorial University via Collections Canada Theses, Newfoundland, retrieved August 5, 2008

- Jeddore, Roderick Joachim (March 2000), "Investigating the restoration of the Miꞌkmaq language and culture on the First Nations reserve of Miawpukek" (PDF), University of Saskatchewan (Master's), Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, retrieved August 5, 2016

- Jackson, Doug (1993). On the country: The Micmac of Newfoundland. St. John's, Newfoundland: Harry Cuff Publishing. ISBN 0921191804.

References

- Bock, Philip K. (1978). "Micmac". In Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 109–122.

- Brasser, T.J. (1978). "Early Indian-European Contacts". In Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 78–88.

- Davis, Stephen A. (1998). Míkmaq: Peoples of the Maritimes. Nimbus Publishing.

- Joe, Rita; Choyce, Lesley (2005). The Míkmaq Anthology. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1-895900-04-2.

- Johnston, A.J.B.; Francis, Jesse (2013). Niꞌn na L'nu: The Miꞌkmaq of Prince Edward Island. Charlottetown: Acorn Press. ISBN 978-1-894838-93-1.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert, ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Paul, Daniel N. (2000). We Were Not the Savages: A Miꞌkmaq Perspective on the Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations (2nd ed.). Fernwood. ISBN 978-1-55266-039-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prins, Harald E. L. (1996). The Míkmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival. Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology. Wadsworth.

- Robinson, Angela (2005). Tán Teli-Ktlamsitasit (Ways of Believing): Míkmaw Religion in Eskasoni, Nova Scotia. Pearson Education. ISBN 0-13-177067-5.

- Snow, Dean R. (1978). "Late Prehistory of the East Coast: Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Eastern New Brunswick Drainages". In Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 69.

- Speck, Frank (1922). Beothuk and Micmac.

- Whitehead, Ruth Holmes (2004). The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts from Míkmaq History 1500-1950. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 0-921054-83-1.

- Wicken, William C. (2002). Miꞌkmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7665-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

18th–19th centuries

- A Geographic History of Nova Scotia. 1749

- An account of the present state of Nova Scotia Hollingsworth. 1873

- Bromley, Walter (1814). Mr. Bromley's second address, on the deplorable state of the Indians delivered in the "Royal Acadian School," at Halifax, in Nova Scotia, March 8, 1814. [Halifax, N.S.?] : Printed at the Recorder Office.

- Bromley, Walter (1822). An account of the aborigines of Nova Scotia called the Micmac Indians. London? : s.n.

- Dickason, Olive Patricia; Hoad, Linda M. "Louisbourg et les Indiens : une étude des relations raciales de la France, 1713-1760".

- Elder, William (January 1, 1871). "The Aborigines of Nova Scotia". The North American Review.

- Malliard, Antoine Simon (1758). An account of the customs and manners of the MicMakis and Marichetts Savage Nations.

- Thomas Pichon on Miꞌkmaq

- Piers, Harry (1896). Relics of the stone age in Nova Scotia. S.l. : s.n.

- Rand, Silas Tertius (1850). A short statement of facts relating to the history, manners, customs, language, and literature of the Micmac tribe of Indians, in Nova-Scotia and P.E. Island: being the substance of two lectures delivered in Halifax, in November, 1819, at public meetings held for the purpose of instituting a mission to that tribe. Halifax, N.S.? : s.n.

- Rand and the Micmacs

- Vetromile, Eugene (1866). The Abnakis and their history: Historical notices on the aborigines of Acadia. New York : J.B. Kirker.

- Miꞌkmaq Language, 1797

- Upton, L.F.S. (1979). Micmacs and Colonists: Indian-White Relations in the Maritimes 1713-1867. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0114-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mi'kmaq. |

- Qalipu First Nation

- Benoit First Nation

- Bras D'Or First Nation

- Bras d'Or - Pitawpoꞌq, Indian name; Little Bras d'Or - Panuꞌskek, Indian name

- Micmac History

- Míkmaq Portraits Collection

- Miꞌkmaq Language. Mass Historical Society

- Míkmaq Dictionary Online

- The Micmac of Megumaagee

- Míkmaq Learning Resource

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Unamaꞌki Institute of Natural Resources

- Miꞌkmaw Native Friendship Centre

.jpg)