Burying the Hatchet ceremony (Nova Scotia)

The Burying the Hatchet Ceremony (also known as the Governor's Farm Ceremony) happened in Nova Scotia on June 25, 1761 and was one of many such ceremonies where the Halifax Treaties[1] were signed. The treaties ended a protracted period of warfare which had lasted more than 75 years and encompassed six wars between the Mi'kmaq people and the British. The Burying the Hatchet Ceremonies and the treaties that they commemorated created an enduring peace and a commitment to obey the rule of law.

Many of British commitments were not delivered on, despite the intentions of the British dignitaries who attended the ceremony and helped draft the treaty, such as the right afforded to the Mi'kmaq for becoming British subjects. The treaties were enshrined into the Canadian Constitution in 1982, and there have since been numerous judicial decisions that have upheld them in the Canadian Supreme Court, the most recognized being the Donald Marshall case. Nova Scotians celebrate the Treaties of 1760-61 every year on Treaty Day (October 1).

Historical context

The northeastern region of North America encompassing New England and Acadia increasingly became an area of conflict between the French and British Empires, and there was a long history of the Wabanaki Confederacy (which included the Mi'kmaq) killing British colonists along the border of New England and Acadia in Maine. Several Governors of the Massachusetts Bay Colony attempted to prevent these French and Wabanaki massacres by issuing a bounty for the scalps of men of the Wabanaki Confederacy.[2] During Father Le Loutre's War, Edward Cornwallis followed that example after the Raid on Dartmouth (1749) when he attempted to protect the first British settlers in Nova Scotia from being scalped by putting a bounty on the Mi'kmaq (1749).

The final period of this conflict was the French and Indian War, when French officers, Mi'kmaq, and Acadians carried out military strikes against the New Englanders, particularly after the deportation of the Acadians and the bounty proclamation of 1756. The Mi'kmaq and their French allies conducted the Northeastern Coast Campaign (1755) in Maine and extended this campaign into Nova Scotia, attacking civilians during the raids on Lunenburg. The British captured Louisbourg in 1758 and battled Quebec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760, and the French imperial power was destroyed in North America. With the loss of their French ally, the Mi'kmaq recognized the need for a new relationship with the British colonists.

There were various treaties signed with other tribes of the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet before the formal burying the hatchet ceremony. On 11 February 1760, two tribes of the Passamaquoddy and Saint John River came to Halifax with Colonel Arbuthnot and appeared before council, renewing the treaty of 1725 and giving hostages for their good behavior. On Feb 13, a treaty was ratified with Roger Morris and one of the Mi'kmaq chiefs.[3] On 10 March 1760, Mi'kmaq chiefs Paul Laret, Michael Austine, and Calude Renie made a treaty.[4] On 15 October 1761, Jannesvil Peitougashwas (Pictock and Malogomish) made a treaty.[4]

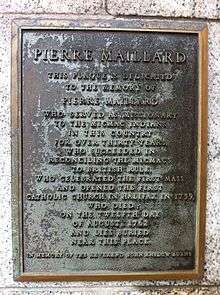

French priest Pierre Maillard accepted an invitation from Nova Scotia Governor Charles Lawrence to travel to Halifax and assist in negotiating with the Mi'kmaq peoples. He also received permission to maintain an oratory at a Halifax battery, where he held Catholic services for Acadians and Mi'kmaqs in the area.[5] In his official capacity, Maillard was able to persuade most of the tribal chiefs to sign peace treaties with the British in Halifax.

The Ceremony

On June 25, 1761,[6] a "Burying of the Hatchet Ceremony" was held at Governor Jonathan Belcher's garden on present-day Spring Garden Road, Halifax in front of the Court House.

Representing the colony were Belcher and four members of the Nova Scotia Council: Richard Bulkeley, John Collier,[7] Joseph Gerrish,[8] and Alexander Grant.[9] Also present were Admiral Lord Colville, commander-in-chief of British naval forces in North America, Major-General John Henry Bastide, the chief engineer in Nova Scotia and Colonel William Forster, the commander of Nova Scotia's army regiments. These three men were accompanied by a detachment of soldiers.[10]

There were at least four Mi'kmaq chiefs that signed the treaty: Jeannot Peguidalonet (representing Cape Breton), Claude Atouach (Shediac), Joseph Sabecholouet (Miramichi), and Aikon Ashabuc (Pokemouche). Representatives from other villages were also present at the treaty signing.[10]

The occasion was one of "great pomp and ceremony". The two parties faced each other near a British flag. French priest Pierre Maillard was in the middle acting as the interpreter. Belcher promised the crown would protect the Mi'kmaq from unscrupulous traders, protect their religion and not interfere with Catholic missionaries living among them. Belcher gave presents to each chief along with medals that were passed down through generations as testimony to the words that bound their people to uphold the peace. Both Belcher and the chiefs then moved to the flag post, where Belcher and the chiefs formally buried the hatchet.[10]

One of the Mi'kmaq Chiefs declared that "he now buried the hatchet on behalf of himself and his whole tribe, a token of their submission and of their having made peace."[11] The Chief of the Cape Breton Mi'kmaq's declared: "As long as the Sun and the Moon shall endure, as long as the Earth on which I dwell shall exist in the same State as you this day, with the Laws of your Government, faithful and obedient to the Crown".[12]

At the same time the hatchet was being buried, the Chiefs went through the ceremony of washing the paint from their bodies in token of hostilities being ended. The whole ceremony was concluded by all present drinking to the king's health. The cornerstone of the Halifax Provincial Court (Spring Garden Road) now stands beside the spot of the burial, a symbol of peace and the rule of law.[13]

Aftermath

The Halifax Treaties effectively established peace between the Mi'kmaq and the British by both committing to uphold the rule of law. Historians disagree about whether or not the Treaties reflect that the Mi'kmaq surrendered or not to the British.[1] Daniel N. Paul notes that the wording of the document ascribed to the Chiefs uses language and knowledge of European conventions that would be incomprehensible or unknown to the Mi'kmaq.[14]

See also

References

- Endnotes

- Patterson, Stephen (2009). "Eighteenth-Century Treaties:The Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy Experience" (PDF). Native Studies Review. 18 (1).

- A particular history of the five years French and Indian War in New England ... By Samuel Gardner Drake, William Shirley. p. 134

- (Atkins, p. 64)

- (Atkins, p. 65)

- These services were held "with great freedom" according to Maillard's report. Dictionary

- Some accounts give the date as 8 July 1761

- Hamilton, William B. (1974). "Collier, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Patterson, Stephen E. (1979). "Gerrish, Joseph". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Alexander Grant, Esq. of London who moved to Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1760. He apparently received an appointment as Indian Commerce Contractor for Canada and as Agent Victualer to His Majesty's Ships at Halifax. I have also found a vague reference to him being a member of His Majesty's Council of Nova Scotia from which point he was referred to as the Hon. Alexander Grant Esq. Alexander returned to London about 1766.

- Wicken, p. 216

- Thomas Radall. Halifax: Warden of the North. p. 62

- Stephen Patterson. Atlantic Canada to Confederation. p. 150

- Atkins, History of Halifax. p. 66; Radall,

- Paul 2006, p. 168.

- Texts

- Paul, Daniel N. (2006). We Were Not the Savages: Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations (3rd ed.). Fernwood. ISBN 978-1-55266-209-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Stephen. "Eighteenth-Century Treaties:The Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy Experience" (PDF). Native Studies Review (18, no. 1 (2009)).

- Reid, John G. (2009). "Empire, the Maritime Colonies, and the Supplanting of Mi'kma'ki/Wulstukwik, 1780-1820". Acadiensis. 38 (2): 78–97. JSTOR 41501739.

- Baker, Emerson W.; Reid, John G. (January 2004). "Amerindian Power in the Early Modern Northeast: A Reappraisal". William and Mary Quarterly. Third Series. 61: 77–106. doi:10.2307/3491676. JSTOR 3491676.

- Wicken, William C. (2002). Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press. pp. 215–218. ISBN 978-0-8020-7665-6.

.jpg)