Melodrama

A melodrama is a dramatic work wherein the plot, which is typically sensational and designed to appeal strongly to the emotions, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue, which is often bombastic or excessively sentimental, rather than action. Characters are often simply drawn and may appear stereotyped. Melodramas are typically set in the private sphere of the home, and focus on morality and family issues, love, and marriage, often with challenges from an outside source, such as a "temptress", a scoundrel, or an aristocratic villain. A melodrama on stage, filmed or on television is usually accompanied by dramatic and suggestive music that offers cues to the audience of the drama being presented.

In scholarly and historical musical contexts, melodramas are Victorian dramas in which orchestral music or song was used to accompany the action. The term is now also applied to stage performances without incidental music, novels, movies, television and radio broadcasts. In modern contexts, the term "melodrama" is generally pejorative,[1] as it suggests that the work in question lacks subtlety, character development, or both. By extension, language or behavior which resembles melodrama is often called melodramatic; this use is nearly always pejorative.

Etymology

The term originated from the early 19th-century French word mélodrame. It is derived from Greek μέλος mélos, "song, strain" (compare "melody", from μελωδία melōdia, "singing, song"), and French drame, drama (from Late Latin drāma, eventually deriving from classical Greek δράμα dráma, "theatrical plot", usually of a Greek tragedy).[2][3][4]

Characteristics

The relationship of melodrama compared to realism is complex. The protagonists of melodramatic works may either be ordinary (and hence realistically drawn) people who are caught up in extraordinary events, or highly exaggerated and unrealistic characters. Peter Brooks writes that melodrama, in its high emotions and dramatic rhetoric, represents a "victory over repression."[5] According to Singer, late Victorian and Edwardian melodrama combined a conscious focus on realism in stage sets and props with "anti-realism" in character and plot. Melodrama in this period strove for "credible accuracy in the depiction of incredible, extraordinary" scenes.[6] Novelist Wilkie Collins is noted for his attention to accuracy in detail (e.g. of legal matters) in his works, no matter how sensational the plot. Melodramas were typically 10 to 20,000 words in length. [7]

Melodramas put most of their attention on the victim and a struggle between good and evil choices, such as a man being encouraged to leave his family by an "evil temptress".[8] Other stock characters are the "fallen woman", the single mother, the orphan and the male who is struggling with the impacts of the modern world.[9] The melodrama examines family and social issues in the context of a private home, with its intended audience being the female spectator; secondarily, the male viewer is able to enjoy the onscreen tensions in the home being resolved.[10] Melodrama generally looks back at ideal, nostalgic eras, emphasizing "forbidden longings". [11]

Types

Origins

The melodrama approach was revived in the 18th- and 19th-century French romantic drama and the sentimental novels that were popular in both England and France.[12] These dramas and novels focused on moral codes in regards to family life, love, and marriage, and they can be seen as a reflection of the issues brought up by the French Revolution, the industrial revolution and the shift to modernization.[12] Many melodramas were about a middle-class young woman who experienced unwanted sexual advances from an aristocratic miscreant, with the sexual assault being a metaphor for class conflict.[12] The melodrama reflected post-industrial revolution anxieties of the middle class, who were afraid of both aristocratic power brokers and the impoverished working class "mob".[12]

Beginning in the 18th century, melodrama was a technique of combining spoken recitation with short pieces of accompanying music. In such works, music and spoken dialogue typically alternated, although the music was sometimes also used to accompany pantomime.

The earliest known examples are scenes in J. E. Eberlin's Latin school play Sigismundus (1753). The first full melodrama was Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Pygmalion,[13] the text of which was written in 1762 but was first staged in Lyon in 1770. The overture and an Andante were composed by Rousseau, but the bulk of the music was composed by Horace Coignet.

A different musical setting of Rousseau's Pygmalion by Anton Schweitzer was performed in Weimar in 1772, and Goethe wrote of it approvingly in Dichtung und Wahrheit. Pygmalion is a monodrama, written for one actor.

Some 30 other monodramas were produced in Germany in the fourth quarter of the 18th century. When two actors were involved, the term duodrama could be used. Georg Benda was particularly successful with his duodramas Ariadne Auf Naxos (1775) and Medea (1778). The sensational success of Benda's melodramas led Mozart to use two long melodramatic monologues in his opera Zaide (1780).

Other later, and better-known examples of the melodramatic style in operas are the grave-digging scene in Beethoven's Fidelio (1805) and the incantation scene in Weber's Der Freischütz (1821).[14][15]

After the English Restoration of Charles II in 1660, most British theatres were prohibited from performing "serious" drama, but were permitted to show comedy or plays with music. Charles II issued letters patent to permit only two London theatre companies to perform "serious" drama. These were the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and Lisle's Tennis Court in Lincoln's Inn Fields, the latter of which moved to the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in 1720 (now the Royal Opera House). The two patent theatres closed in the summer months. To fill the gap, the Theatre Royal, Haymarket became a third patent theatre in London in 1766.

Further letters patent were eventually granted to one theatre in each of several other English towns and cities. To get around the restriction, other theatres presented dramas that were underscored with music and, borrowing the French term, called it melodrama. The Theatres Act 1843 finally allowed all the theatres to play drama.[16]

19th century: operetta, incidental music, and salon entertainment

In the early 19th century, the influence of opera led to musical overtures and incidental music for many plays. In 1820, Franz Schubert wrote a melodrama, Die Zauberharfe ("The Magic Harp"), setting music behind the play written by G. von Hofmann. It was unsuccessful, like all Schubert's theatre ventures, but the melodrama genre was at the time a popular one. In an age of underpaid musicians, many 19th-century plays in London had an orchestra in the pit. In 1826, Felix Mendelssohn wrote his well-known overture to Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, and later supplied the play with incidental music.

In Verdi's La Traviata, Violetta receives a letter from Alfredo's father where he writes that Alfredo now knows why she parted from him and that he forgives her ("Teneste la promessa..."). In her speaking voice, she intones the words of what is written, while the orchestra recapitulates the music of their first love from Act I: this is technically melodrama. In a few moments Violetta bursts into a passionate despairing aria ("Addio, del passato"): this is opera again.

In a similar manner, Victorians often added "incidental music" under the dialogue to a pre-existing play, although this style of composition was already practiced in the days of Ludwig van Beethoven (Egmont) and Franz Schubert (Rosamunde). (This type of often-lavish production is now mostly limited to film (see film score) due to the cost of hiring an orchestra. Modern recording technology is producing a certain revival of the practice in theatre, but not on the former scale.) A particularly complete version of this form, Sullivan's incidental music to Tennyson's The Foresters, is available online,[17] complete with several melodramas, for instance, No. 12 found here.[18] A few operettas exhibit melodrama in the sense of music played under spoken dialogue, for instance, Gilbert and Sullivan's Ruddigore (itself a parody of melodramas in the modern sense) has a short "melodrame" (reduced to dialogue alone in many productions) in the second act;[19] Jacques Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld opens with a melodrama delivered by the character of "Public Opinion"; and other pieces from operetta and musicals may be considered melodramas, such as the "Recit and Minuet"[20] in Gilbert and Sullivan's The Sorcerer. As an example from the American musical, several long speeches in Lerner and Loewe's Brigadoon are delivered over an accompaniment of evocative music. The technique is also frequently used in Spanish zarzuela, both in the 19th and 20th centuries, and continued also to be used as a "special effect" in opera, for instance Richard Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten.

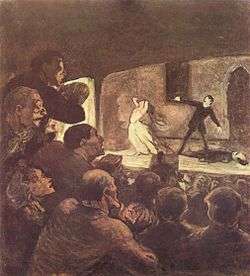

In Paris, the 19th century saw a flourishing of melodrama in the many theatres that were located on the popular Boulevard du Crime, especially in the Gaîté. All this came to an end, however, when most of these theatres were demolished during the rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann in 1862.[21]

By the end of the 19th century, the term melodrama had nearly exclusively narrowed down to a specific genre of salon entertainment: more or less rhythmically spoken words (often poetry) – not sung, sometimes more or less enacted, at least with some dramatic structure or plot – synchronised to an accompaniment of music (usually piano). It was looked down on as a genre for authors and composers of lesser stature (probably also the reason why virtually no realizations of the genre are still remembered). Probably also the time when the connotation of cheap overacting first became associated with the term. As a cross-over genre-mixing narration and chamber music, it was eclipsed nearly overnight by a single composition: Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire (1912), where Sprechgesang was used instead of rhythmically spoken words, and which took a freer and more imaginative course regarding the plot prerogative.

Opera

The great majority of operas are melodramas. The emotional tensions are both communicated and amplified by the appropriate music. The majority of plots involve characters overcoming or succumbing to larger than life events of war, betrayal, monumental love, murder, revenge, filial discord or similar grandiose occurrences. Most characters are simplistically drawn with clear distinctions between virtuous and evil ones and character development and subtlety of situations is sacrificed. Events are arranged to fit with the character's traits to best demonstrate their emotional effects on the character and others.

The predominance of melodrama in bel canto works of Donizzetti, Bellini and virtually all Verdi and Puccini is clear with examples too numerous to list. The great multitude of heroines needing to deal with and overcome situations of love impossible in the face of grandiose circumstances is amply exemplified by Lucia, Norma, Leonora, Tosca, Turandot, Mimi, Cio-Cio-San Violetta, Gilda and many others.

Czech

Within the context of the Czech National Revival, the melodrama took on a specifically nationalist meaning for Czech artists, beginning roughly in the 1870s and continuing through the First Czechoslovak Republic of the interwar period. This new understanding of the melodrama stemmed primarily from such nineteenth-century scholars and critics as Otakar Hostinský, who considered the genre to be a uniquely "Czech" contribution to music history (based on the national origins of Georg Benda, whose melodramas had nevertheless been in German). Such sentiments provoked a large number of Czech composers to produce melodramas based on Czech romantic poetry such as the Kytice of Karel Jaromír Erben.

The romantic composer Zdeněk Fibich in particular championed the genre as a means of setting Czech declamation correctly: his melodramas Štědrý den (1874) and Vodník (1883) use rhythmic durations to specify the alignment of spoken word and accompaniment. Fibich's main achievement was Hippodamie (1888–1891), a trilogy of full-evening staged melodramas on the texts of Jaroslav Vrchlický with multiple actors and orchestra, composed in an advanced Wagnerian musical style. Josef Suk's main contributions at the turn of the century include melodramas for two-stage plays by Julius Zeyer: Radúz a Mahulena (1898) and Pod Jabloní (1901), both of which had a long performance history.

Following the examples of Fibich and Suk, many other Czech composers set melodramas as stand-alone works based on poetry of the National Revival, among them Karel Kovařovic, Otakar Ostrčil, Ladislav Vycpálek, Otakar Jeremiáš, Emil Axman, and Jan Zelinka. Vítězslav Novák included portions of melodrama in his 1923 opera Lucerna, and Jaroslav Ježek composed key scenes for the stage plays of the Osvobozené divadlo as melodrama (most notably the opening prologue of the anti-Fascist farce Osel a stín (1933), delivered by the character of Dionysus in bolero rhythm). The practice of Czech melodramas tapered off after the Nazi Protectorate.

Victorian

The Victorian stage melodrama featured six stock characters: the hero, the villain, the heroine, an aged parent, a sidekick and a servant of the aged parent engaged in a sensational plot featuring themes of love and murder. Often the good but not very clever hero is duped by a scheming villain, who has eyes on the damsel in distress until fate intervenes at the end to ensure the triumph of good over evil.[22] Two central features were the coup de théàtre, or reversal of fortune, and the claptrap: a back-to-the-wall oration by the hero which forces the audience to applaud.[23]

English melodrama evolved from the tradition of populist drama established during the Middle Ages by mystery and morality plays, under influences from Italian commedia dell'arte as well as German Sturm und Drang drama and Parisian melodrama of the post-Revolutionary period.[24] A notable French melodramatist was Pixérécourt whose La Femme à deux maris was very popular.[25]

The first English play to be called a melodrama or 'melodrame' was A Tale of Mystery (1802) by Thomas Holcroft. This was an example of the Gothic genre, a previous theatrical example of which was The Castle Spectre (1797) by Matthew Gregory Lewis. Other Gothic melodramas include The Miller and his Men (1813) by Isaac Pocock, The Woodsman's Hut (1814) by Samuel Arnold and The Broken Sword (1816) by William Dimond.

Supplanting the Gothic, the next popular subgenre was the nautical melodrama, pioneered by Douglas Jerrold in his Black-Eyed Susan (1829). Other nautical melodramas included Jerrold's The Mutiny at the Nore (1830) and The Red Rover (1829) by Edward Fitzball (Rowell 1953).[22] Melodramas based on urban situations became popular in the mid-nineteenth century, including The Streets of London (1864) by Dion Boucicault; and Lost in London (1867) by Watts Phillips, while prison melodrama, temperance melodrama, and imperialist melodrama also appeared – the latter typically featuring the three categories of the 'good' native, the brave but wicked native, and the treacherous native.[26]

The sensation novels of the 1860s and 1870s not only provided fertile material for melodramatic adaptations but are melodramatic in their own right. A notable example of this genre is Lady Audley's Secret by Elizabeth Braddon adapted, in two different versions, by George Roberts and C.H. Hazlewood. The novels of Wilkie Collins have the characteristics of melodrama, his best-known work The Woman in White being regarded by some modern critics as "the most brilliant melodrama of the period".[27]

The villain is often the central character in melodrama and crime was a favorite theme. This included dramatizations of the murderous careers of Burke and Hare, Sweeney Todd (first featured in The String of Pearls (1847) by George Dibdin Pitt), the murder of Maria Marten in the Red Barn and the bizarre exploits of Spring Heeled Jack. The misfortunes of a discharged prisoner are the theme of the sensational The Ticket-of-Leave Man (1863) by Tom Taylor.

Early silent films, such as The Perils of Pauline had similar themes. Later, after silent films were superseded by the 'talkies', stage actor Tod Slaughter, at the age of 50, transferred to the screen the Victorian melodramas in which he had played a villain in his earlier theatrical career. These films, which include Maria Marten or Murder in the Red Barn (1935), Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1936) and The Ticket of Leave Man (1937) are a unique record of a bygone art-form.

Generic offshoots

- Northrop Frye saw both advertising and propaganda as melodramatic forms which the cultivated cannot take seriously.[28]

- Politics at the time calls on melodrama to articulate a world-view. Thus Richard Overy argues that 1930s Britain saw civilisation as melodramatically under threat - "In this great melodrama Hitler's Germany was the villain; democratic civilization the menaced heroine";[29] - while Winston Churchill provided the necessary larger-than-life melodramatic hero to articulate back-to-the-wall resistance during The Blitz.[30]

Modern

Classic melodrama is less common than it used to be on television and in movies in the Western world. However, it is still widely popular in other regions, particularly in Asia and in Hispanic countries. Melodrama is one of the main genres (along with romance, comedy and fantasy) used in Latin American television dramas (telenovelas), particularly in Venezuela, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina and Brazil, and in Asian television dramas, particularly in South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, China, Pakistan, Thailand, India, Turkey and (in a fusion of the Hispanic and Asian cultures) the Philippines. Expatriate communities in the diaspora of these countries give viewership a global market.

Film

Melodrama films are a subgenre of drama films characterised by a plot that appeals to the heightened emotions of the audience. They generally depend on stereotyped character development, interaction, and highly emotional themes. Melodramatic films tend to use plots that often deal with crises of human emotion, failed romance or friendship, strained familial situations, tragedy, illness, neuroses, or emotional and physical hardship. Victims, couples, virtuous and heroic characters or suffering protagonists (usually heroines) in melodramas are presented with tremendous social pressures, threats, repression, fears, improbable events or difficulties with friends, community, work, lovers, or family. The melodramatic format allows the character to work through their difficulties or surmount the problems with resolute endurance, sacrificial acts, and steadfast bravery.

Film critics sometimes use the term pejoratively to connote an unrealistic, pathos-filled, campy tale of romance or domestic situations with stereotypical characters (often including a central female character) that would directly appeal to feminine audiences."[31] Melodramas focus on family issues and the themes of duty and love.[32] As melodramas emphasize the family unit, women are typically depicted in a subordinate, traditional role, and the woman is shown as facing self-sacrifice and repression.[33] In melodramas, men are shown in the domestic, stereotypically female home environment; as such, to resolve the challenges presented by the story, the male must learn to negotiate this "female" space.[34] Since men who are learning to operate in the domestic sphere appear "less male...and more feminized", this makes melodramas appealing to female viewers.[35] Melodramas place their attention on a victim character.[36]

Since melodramas are set in the home and in a small town, it can be challenging for the filmmaker to create a sense of action given that it all takes place in one claustrophobic sphere; one way to add in more locations is through flashbacks to the past.[37]The sense of being trapped often causes challenges for children, teen and female characters. [38] The sense of being trapped leads to obsessions with unobtainable objects or other people, and to inner aggressiveness or "aggressiveness by proxy".[39] Feminists have noted four categories of themes: those with a female patient, a maternal figure, an "impossible love", and the paranoid melodrama.[40]

Most film melodramas from the 1930s and 1940s, known as "weepies" or "tearjerkers", were adaptations of women's fiction, such as romance novels and historical romances.[41] Melodramas focus on women's subjectivity and perspective and female desire; however, due to the Hay's Code, this desire could not be explicitly shown on screen from the 1930s to the late 1960s, so female desire is de-eroticized.[42]

During the 1940s the British Gainsborough melodramas were successful with audiences. A director of 1950s melodrama films was Douglas Sirk who worked with Rock Hudson on Written on the Wind and All That Heaven Allows, both staples of the genre. Melodramas like the 1990s TV Moment of Truth movies targeted audiences of American women by portraying the effects of alcoholism, domestic violence, rape and the like. Typical of the genre is Anjelica Huston's 1999 film Agnes Browne.[43] In the 1970s, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who was very much influenced by Sirk, contributed to the genre by engaging with class in The Merchant of Four Seasons (1971) and Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven (1975), with sexual orientation and codependency in The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) and with racism, xenophobia and ageism in Fear Eats the Soul (1974). More recently, Todd Haynes has renewed the genre with his 2002 film Far from Heaven.

See also

References

- Brooks, Peter (1995). The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. Yale University Press. p. xv.

- Costello, Robert B., ed. (1991). Random House Webster's College Dictionary. New York: Random House. p. 845. ISBN 978-0-679-40110-0.

- Stevenson, Angus; Lindberg, Christine A., eds. (2010). New Oxford American Dictionary, Third Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1091. ISBN 978-0-19-539288-3.

- Pickett, Joseph P., ed. (2006). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 544, 1095. ISBN 978-0-618-70173-5.

- Brooks, Peter (1995). The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. Yale University Press. p. 41.

- Singer, Ben (2001). Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 44–53.

- Peters, Catherine. The King of Inventors.

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 236

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 236

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cimena Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 236

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 236

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 236

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Apel, Willi, ed. (1969). Harvard Dictionary of Music, Second Edition, Revised and Enlarged. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-674-37501-7. OCLC 21452.

- Branscombe, Peter. "Melodrama". In Sadie, Stanley; John Tyrrell, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition. New York: Grove's Dictionaries. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Fisk, Deborah Payne (2001). "The Restoration Actress", in Owen, Sue, A Companion to Restoration Drama. Oxford: Blackwell.

- The Foresters Archived 2006-09-03 at the Wayback Machine from Gilbert and Sullivan online archive

- "The Foresters - Act I Scene II". Gilbert and Sullivan Archive. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018.

- Gilbert, W. S.; Sullivan, Arthur. "Ruddigore: Dialogue following No. 24". Gilbert and Sullivan Archive.

- Gilbert, W. S.; Sullivan, Arthur. "The Sorcerer: No. 4: Recitative & Minuet". Gilbert and Sullivan Archive.

- The golden age of the Boulevard du Crime Theatre online.com (in French)

- Williams, Carolyn. "Melodrama", in The New Cambridge History of English Literature: The Victorian Period, ed. Kate Flint, Cambridge University Press (2012), pp. 193–219 ISBN 9780521846257

- Rose, Jonathan (2015). The Literary Churchill: Author, Reader, Actor. Yale University Press. pp. 11 and 174. ISBN 9780300212341.

- Booth, Michael Richard (1991). Theatre in the Victorian Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0521348379.

- Jean Tulard (1985) Naploleon: The Myth of the Saviour. London, Methuen: 213-14

- J. Rose, The Literary Churchill (Yale 2015) p. 11-13

- Collins, Wilkie, ed. Julian Symons (1974). The Woman in White (Introduction). Penguin.

- N. Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (Princeton 1971) p. 47

- Quoted in J. Rose, The Literary Churchill (Yale 2015) p. 291

- J. Webb, I Heard My Country Calling (2014) p. 68

- Dirks T Melodrama Films filmsite.org website opinion

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 238

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 238

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 239

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 239

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 240

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 242

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 242

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 242

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 243

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 244

- Hayward, Susan. "Melodrama and Women's Films" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 242-244

- Levy, Emanuel (31 May 1999) "Agnes Browne (period drama)" Variety

External links

| Look up melodrama in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |