Massagetae

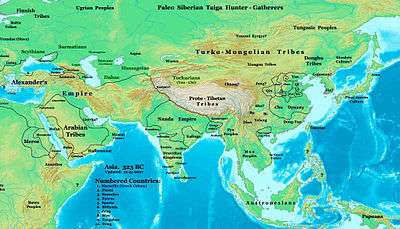

The Massagetae, or Massageteans,[1] were an ancient Eastern Iranian nomadic tribal confederation,[2][3][4][5] who inhabited the steppes of Central Asia, north-east of the Caspian Sea in modern Turkmenistan, western Uzbekistan, and southern Kazakhstan. They were part of the wider Scythian cultures.[6]

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

The Massagetae are known primarily from the writings of Herodotus who described the Massagetae as living on a sizeable portion of the great plain east of the Caspian Sea.[7] He several times refers to them as living "beyond the River Araxes", which flows through the Caucasus and into the west Caspian.[8] Scholars have offered various explanations for this anomaly. For example, Herodotus may have confused two or more rivers, as he had limited and frequently indirect knowledge of geography.[9]

According to Greek and Roman scholars, the Massagetae were neighboured by the Aspasioi (possibly the Aśvaka) to the north, the Scythians and the Dahae to the west, and the Issedones (possibly the Wusun) to the east. Sogdia (Khorasan) lay to the south.[10]

Possible connections to other ancient peoples

Ancient writers

Herodotus stated the Massagetae were great and warlike nation, dwelling beyond the river Araxes and that they are regarded as a Scythian race.

Ammianus Marcellinus considered the Alans to be the former Massagetae.[11] At the close of the 4th century CE, Claudian (the court poet of Emperor Honorius and Stilicho) wrote of Alans and Massagetae in the same breath: "the Massagetes who cruelly wound their horses that they may drink their blood, the Alans who break the ice and drink the waters of Maeotis' lake" (In Rufinem).

Medieval writers

Procopius writes in History of the Wars Book III: The Vandalic War:[12] "the Massagetae whom they now call Huns" (XI. 37.), "there was a certain man among the Massagetae, well gifted with courage and strength of body, the leader of a few men; this man had the privilege handed down from his fathers and ancestors to be the first in all the Hunnic armies to attack the enemy" (XVIII. 54.).

Evagrius Scholasticus (Ecclesiastical History. Book 3. Ch. II.): "and in Thrace, by the inroads of the Huns, formerly known by the name of Massagetae, who crossed the Ister without opposition".[13]

A 9th century work by Rabanus Maurus, De Universo, states: "The Massagetae are in origin from the tribe of the Scythians, and are called Massagetae, as if heavy, that is, strong Getae."[14][15] In Central Asian languages such as Middle Persian and Avestan, the prefix massa means "great", "heavy", or "strong".[16]

Modern writers

Some authors, such as Alexander Cunningham, James P. Mallory, Victor H. Mair, and Edgar Knobloch have proposed relating the Massagetae to the Gutians of 2000 BC Mesopotamia, and/or a people known in ancient China as the "Da Yuezhi" or "Great Yuezhi" (who founded the Kushan Empire in South Asia). Mallory and Mair suggest that Da Yuezhi may at one time have been pronounced d'ad-ngiwat-tieg, connecting them to the Massagetae.[17][18][19] These theories are not widely accepted, however.

Many scholars have suggested that the Massagetae were related to the Getae of ancient Eastern Europe.[20]

Tadeusz Sulimirski notes that the Sacae also invaded parts of Northern India.[21] Weer Rajendra Rishi, an Indian linguist[22] has identified linguistic affinities between Indian and Central Asian languages, which further lends credence to the possibility of historical Sacae influence in Northern India.[16][21]

According to Guive Mirfendereski at the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies (CAIS), the Massagetae are synonymous with the Sakā haumavargā of South Asian historiography.

Rüdiger Schmitt, notes Ptolemy's conflicting reports concerning the Massagetae.[23] First, localizing them near Margiana, then later Ptolemy calls them a tribe of the Saka in the vicinity of the Hindu Kush.[23] Schmitt, who states these terms are not relevant for ancient times, also notes that Byzantine authors used the word Massagetae as an antiquated term for Huns, Turks and Tatars.[23]

Culture

The original language of the Massagetae is little-known. While it appears to have had similarities to the Eastern Iranian languages, these may have resulted from interactions with neighbouring peoples, such as language contact or sprachbund-type assimilation.

According to Herodotus:

[1.215] In their dress and mode of living the Massagetae resemble the Scythians. They fight both on horseback and on foot, neither method is strange to them: they use bows and lances, but their favourite weapon is the battle-axe. Their arms are all either of gold or brass. For their spear-points, and arrow-heads, and for their battle-axes, they make use of brass; for head-gear, belts, and girdles, of gold. So too with the caparison of their horses, they give them breastplates of brass, but employ gold about the reins, the bit, and the cheek-plates. They use neither iron nor silver, having none in their country; but they have brass and gold in abundance.

[1.216] The following are some of their customs; – Each man has but one wife, yet all the wives are held in common; for this is a custom of the Massagetae and not of the Scythians, as the Greeks wrongly say. Human life does not come to its natural close with this people; but when a man grows very old, all his kinsfolk collect together and offer him up in sacrifice; offering at the same time some cattle also. After the sacrifice they boil the flesh and feast on it; and those who thus end their days are reckoned the happiest. If a man dies of disease they do not eat him, but bury him in the ground, bewailing his ill-fortune that he did not come to be sacrificed. They sow no grain, but live on their herds, and on fish, of which there is great plenty in the Araxes River. Milk is what they chiefly drink. The only god they worship is the sun, and to him they offer the horse in sacrifice; under the notion of giving to the swiftest of the gods the swiftest of all mortal creatures.

History

Concerning the death of Cyrus the Great of Persia by the Massagetae, Herodotus writes:

[1.201] When Cyrus had achieved the conquest of the Babylonians, he conceived the desire of bringing the Massagetae under his dominion. Now the Massagetae are said to be a great and warlike nation, dwelling eastward, toward the rising of the sun, beyond the river Araxes, and opposite the Issedones. By many they are regarded as a Scythian race.

[1.211] Cyrus advanced a day's journey into Massagetan territory from the Araxes... Many of the Massagetae were killed, but even more taken prisoner, including Queen Tomyris's son, who was commander of the army and whose name was Spargapises.

[1.214] Tomyris mustered all her forces and engaged Cyrus in battle. I consider this to have been the fiercest battle between non-Greeks that there has ever been.... They fought at close quarters for a long time, and neither side would give way, until eventually the Massagetae gained the upper hand. Most of the Persian army was wiped out there, and Cyrus himself died too.

See also

References

- Engels, Donald W. (1978). Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army. California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04272-7.

- Karasulas, Antony. Mounted Archers Of The Steppe 600 BC-AD 1300 (Elite). Osprey Publishing, 2004, ISBN 184176809X, p. 7.

- Wilcox, Peter. Rome's Enemies: Parthians and Sassanids. Osprey Publishing, 1986, ISBN 0-85045-688-6, p. 9.

- Gershevitch, I.; Fisher, William Bayne; Boyle, John Andrew; Yarshater, Ehsan; Frye, Richard Nelson (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780521200912.

- Grousset, René. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1989, ISBN 0-8135-1304-9, p. 547.

- Unterländer, Martina (March 3, 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

During the first millennium BCE, nomadic people spread over the Eurasian Steppe from the Altai Mountains over the northern Black Sea area as far as the Carpathian Basin... Greek and Persian historians of the 1st millennium BCE chronicle the existence of the Massagetae and Sauromatians, and later, the Sarmatians and Sacae: cultures possessing artefacts similar to those found in classical Scythian monuments, such as weapons, horse harnesses and a distinctive ‘Animal Style' artistic tradition. Accordingly, these groups are often assigned to the Scythian culture...

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Herodotus, The Histories, 1.204.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 1.202.

- Herodotus, The Histories, translation by Robin Waterfield, with notes by Carolyn Deward (1998), p. 613, notes on 1.201-16.

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel

- Ammianus Marcellinus: "iuxtaque Massagetae Halani et Sargetae"; "per Albanos et Massagetas, quos Alanos nunc appellamus"; "Halanos pervenit, veteres Massagetas".

- Procopius: History of the Wars. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/History_of_the_Wars/Book_III

- Ecclesiastical History. Book 3. http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/evagrius_3_book3.htm

- Maurus, Rabanus (1864). Migne, Jacques Paul (ed.). De universo. Paris.

The Massagetae are in origin from the tribe of the Scythians, and are called Massagetae, as if heavy, that is, strong Getae.

- Dhillon, Balbir Singh (1994). History and study of the Jats: with reference to Sikhs, Scythians, Alans, Sarmatians, Goths, and Jutes (illustrated ed.). Canada: Beta Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 1-895603-02-1.

- Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95.

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000), The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, London: Thames & Hudson. pages 98-99

- John F. Haskins (2016). Pazyrik - The Valley of the Frozen Tombs. Read Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4733-5279-7.

- THE STRONGEST TRIBE, Yu. A. Zuev, page 33: "Massagets of the earliest ancient authors... are the Yuezhis of the Chinese sources"

- Leake, Jane Acomb (1967). The Geats of Beowulf: a study in the geographical mythology of the Middle Ages (illustrated ed.). University of Wisconsin Press. p. 68.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114.

The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas)/Massagetan tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India.

- Indian Institute of Romani Studies Archived 2013-01-08 at Archive.today

- Schmitt 2018.

External links

- Herodotus Histories

- Ammianus Marcellinus

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2018). "MASSAGETAE". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)