Tamil Muslim

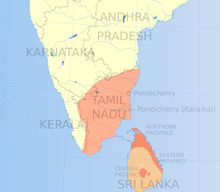

Tamil Muslims are Tamils who practise Islam. The community is at least 4.5 million people in India, primarily in the state of Tamil Nadu. In Tamil Nadu, Muslims consider themselves as "Tamils" but Tamil-speaking Muslims in Sri Lanka are classified as Moors due to independent lineage.[1][2] The Tamil-speaking Muslims are the descendants of the marriages between early Arab Muslim traders of the high seas and indigenous Tamil women, and also of local converts.[3]

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India, Malaysia, Singapore, Europe, Gulf states, Brunei | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tamil people |

| Part of a series on |

| Tamils |

|---|

|

|

|

People

|

Tamil Australians, French Tamils, British Tamils, Tamil Italians, Tamil Indonesians, Tamil Canadians, Tamil Americans, Tamil South Africans, Myanmar Tamils, Tamil Mauritians, Tamil Germans, Tamil Pakistanis, Tamil Seychellois, Tamil New Zealanders, Swiss Tamils, Dutch Tamils |

|

Politics

|

|

|

The community is predominantly urban. There is a substantial diaspora, particularly in Southeast Asia, which has seen their presence as early as the 13th century. In the late 20th century, the diaspora expanded to Western Europe, Gulf Countries and North America [4]

Ethnic identity

Though numerically nominal and collaborative, the community is not homogeneous. Its origin is shaped by miscegenation and centuries of trade between the Bay of Bengal and the Maritime Southeast Asia. By the 20th century, certain Tamil races began to be listed as social classes in official gazettes of different nations as Marakayar, Rowther and Labbay.[5][6][7][8]

Marakkayar

Of Arab descent, the Marakayar sect has dominated the educational side in Tamil Nadu since the 17th century.[3] One notable sea-faring merchant, as recorded in the Chronicles of Thondaiman, was Periya Thambi Nainar Marakkayar who is widely believed to be the first rupee millionaire in the community. His son Seethakaathi, an altruist, commissioned the penning of Seerapuranam by Umaru Pulavar, A. M. M Mohammad Ibrahim Sahib alias Irumbukadai as the philanthropist in the mid 20th century and B. S. Abdur Rahman as the first dollar billionaire. The 11th president of India A. P. J. Abdul Kalam was also born to a Marakkayar boat-builder.[9][10][3]

Rowther

Labbay

Similar to Gurukkal, the Labbay sect mainly engages in religious scholarship. The term ‘Lebbai’ is usually taken to mean people who are religious or follow religious occupations. The resemblance to the Hebrew ‘Levi’ (priest) is curious. Some try to trace the word to Arabic, thus investing it with a certain prestige and sacredness. The Arabic Labbaik, from which lebbai is believed to be derived, can be understood in the sense of submission to God or a master, whence the claim that the Lebbais were originally a religious people.[3]

Economy

In Tamil Nadu, the community is well known as rentiers, entrepreneurs, gemstone jewellers and money changers with above State-average GDP per capita incomes.[11]

Culture

Legends and rituals

As a mark of modesty, women usually wear white thuppatti (whilst travelling only) which is draped over their body on top of the saree but revealing face. Many visit dargah on major life milestones like births, marriages and deaths.[12]

Weddings have retained several Rajput traditions across generations like grooms going on a horseback procession.

Art

Music involves distinctively the Turkish daf and other percussion instruments.

Cuisine

Cuisine is a tell-tale syncretic mixture of Tamil and other Asian recipes.[13] Biriyani is the favourite dish in banquets while mild Malay-style congee is the favourite during the fasting month of Ramadan. There are many regional improvisations. For instance, dumroot, a semolina ghee cake with soft centre and hard crust at the top, is popular in the deltaic households.[14]

Literature

Culture and literature are heavily influenced by the Qadiri flavour of Sufism. Their domain range from mystical to medical, from fictional to political, from philosophical to legal and spiritual.[15][16]

The earliest literary works in the community could be traced to a work titled Palsanthmalai, a small work of eight stanzas. It was written sometime between the 12th and 14th centuries.[17] In 1572, Seyku Issaku, better known as Vanna Parimala Pulavar, published Aayira Masala Venru Vazhankum Adisaya Puranam detailing the Islamic principles and beliefs in a FAQ format. In 1592, Aali Pulavar wrote the Mikurasu Malai. The epic Seerapuranam by Umaru Pulavar is dated to the 17th century[18] and still considered as the crowning achievement in canonical literature.[17] Other significant works of 17th century include Thiruneri Neetham by Sufi master Pir Mohammad, Kanakabhisheka Malai by Seyku Nainar Khan (alias Kanakavirayar), Tirumana Katchi by Sekathi Nainar and the Iraqi war ballad Sackoon Pataippor.[19]

Nevertheless, an independent identity evolved only in the last quarter of the 20th century triggered by the rise of Dravidian politics as well as the introduction of new mass communications and lithographic technologies.[20][21] The world's first Tamil Islamic Literature Conference was held in Trichy in 1973. In early 2000. the Department of Tamil Islamic Literature was set up in the University of Madras.[22] Modern notable writers include Mu Metha and Pavalar Inqulab,[23]

Law and polity

Pre-independence

P. Kalifulla served as the minister for public works in the Cabinet of Kurma Venkata Reddy Naidu in 1937. He was sympathetic to the cause of Periyar E. V. Ramasamy and his Self-Respect Movement. He spoke against the introduction of compulsory Hindi classes in the Madras legislature and participated in the anti-Hindi agitations. He was a lawyer by profession and was known by the honorifics Khan Bahadur. He became the Dewan of Pudukottai after withdrawal from political work. Sir Mohammad Usman was the most prominent among the early political leaders of the community. In 1930, Jamal Mohammad became the president of the Madras Presidency Muslim League.[24] Until then, the party was dominated by Urdu speakers. Yakub Hasan Sait served as a minister in the Rajaji administration. Allama Karim Gani, veteran freedom fighter and a close associate of Subash Chandra Bose, who hailed from Ilayangudi, served as Information Minister in Netaji ministry during the 1930s.

Post-independence

Since the late 20th century, politicians like Quaid-e-Millat (first President of Indian Union Muslim League) and Dawood Shah advocated Tamil to be made an official language of India due to its antiquity in parliamentary debates[25] The community was united in a single political party under Quaid-e-Millath presidency for 27 years keeping rabble-rousers away until his death in 1972. His support was invaluable for ruling parties in the state, as well as in the Centre. He was instrumental in framing and obtaining the minority status and privileges for minorities in India thus safeguarding the Constitution of India. His newspaper Urimaikkural was a very popular daily.

S. M. Muhammed Sheriff, a.k.a. Madurai Sheriff Sahib was a charismatic and prominent leader groomed by Quaid-e-Millath. He was the first elected IUML MP from Tamil Nadu. He produced clear documentary evidence that Kachchatheevu belonged to India. During the Emergency, he was the advisor to the Governor. M. M. Ismail became Chief Justice in 1979 and was sworn in as Acting Governor of Tamil Nadu in 1980. As Kamban Kazhagam president, he organised literary festivals, that focussed on classical Tamil literature. Justice S. A. Kader who was the Judge of Madras High Court during 1983-89 became the President of Tamil Nadu State Government Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission on retirement.[26] In the early 1990s, the Indian National League split from the IUML.[27] The non-denominational social reform movements (called Ghair Muqallid) began to take the front stage (supposedly to fight superstition creep) spearheaded by P. Jainulabdeen further weakening the IUML and causing unrest among community elders who preferred status quo and conservatism. Nevertheless, the Tamil Nadu Muslim Munnetra Kazagham was constituted in 1995. This non-profit organisation quickly became popular and assertive among the working class youth.

21st century

In 2009, the Manithaneya Makkal Katchi, the political arm of TMMK was formed. The TMMK itself split to form the break-away organisation Tamil Nadu Thowheed Jamath soon. In 2011, MMK won 2 of 3 contested Assembly seats viz. Ambur (A. Aslam Basha) and Ramanathapuram (M. H. Jawahirullah). But in 2016, MMK was defeated in all 4 contested seats. Broadly speaking, the community vote bank tends to support laissez faire and free trade; and have been unimpressed by Communism as a public policy though fringe working class factions often called for affirmative action in the last quarter of the 20th century.[28] New generation of leaders like Daud Sharifa Khanum have been active in pioneering social reforms like independent mosques for women.[29][30][31][32] MLAs and MPs such as A. Anwar Rhazza, J. M. Aaroon Rashid, Abdul Rahman, Jinna, Khaleelur Rahman, S. N. M. Ubayadullah, Hassan Ali and T. P. M. Mohideen Khan are found across all major Dravidian political parties like DMK, DMDK and AIADMK, as well as national parties like the INC. At the age of 30, the award-winning documentarian Aloor Shanavas became the Deputy General Secretary of Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi.[33][34]

Notable Tamil Muslims

References

- Mines, Mattison (1978). "Social stratification among the Muslims in Tamil Nadu, South India". In Ahamed, Imtiaz (ed.). Caste and Social Stratification Among Muslims in India. Manohar.

- Muslim Merchants – The Economic Behaviours of the Indian Muslim Community, Shri Ram Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources, New Delhi, 1972

- Jean-Baptiste, Prashant More (1991). "THE MARAKKAYAR MUSLIMS OF KARIKAL, SOUTH INDIA". Journal of Islamic Studies. 2: 25–44 – via JSTOR, Oxford Academic Journals.

- Sayeed, A. R. (1977). "Indian Muslims and some Problems of Modernisation". In Srinivas, M. N. (ed.). Dimensions of Social Change in India. p. 217.

- Tamil Muslims dominate restaurant industry in Malaysia Archived 2010-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Appadurai, Arjun (1977). "Kings, Sects and Temples in South India, 1350-1700 A.D". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. XIV (1).

- Hiltebeitel, A (1999) Rethinking India's oral and classical epics. p. 376 (11). University of Chicago Press.ISBN 0-226-34050-3

- Zafar Anjum, Indians Roar In The Lion City. littleindia.com

- S. Arunachalam, The History of Pearl Fishery of Tamil Coast, Annamalai Nagar 1952, p. 11

- Sanjay Subramanian, The Political Economy of Commerce, Southern India 1500 – 1650, New York 1990

- Tyabji, Amina (1991). "Minority Muslim Businesses in Singapore". In Ariff, Mohamed (ed.). The Muslim Private Sector in Southeast Asia: Islam and the Economic Development of Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 60. ISBN 978-9-81301-609-5.

- Stephen F' Dale Recent Researches on the Islamic Communities of Peninsular India, Studies in South India, ed. Robert E. Frykenbers and Paulin Kolenda (Madras 1985)

- Business Line Archived 15 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Dumroot is a speciality of delta cuisine>

- Islam in Tamilnadu: Varia. (PDF) Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- 216th year commemoration today: Remembering His Holiness Bukhary Thangal Sunday Observer – 5 January 2003. Online version Archived 2012-10-02 at the Wayback Machine accessed on 2009-08-14

- Narayanan, Vasudha (2003). "Religious Vocabulary and Regional Identity: A Study of the Tamil Cirappuranam ('Life of the Prophet')". In Eaton, Richard M. (ed.). India's Islamic Traditions, 711-1750. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 393–408. ISBN 0-19-568334-X.

- The Diversity in Indian Islam. International.ucla.edu. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- N. A. Ameer Ali, Vallal Seethakkathiyin Vaazhvum Kaalamum, Madras 1983, p. 30-31, Ka. Mu. Sheriff, Vallal Seethakkathi Varalaru, 1986, pp. 60–62, M. Idris Marakkayar, Nanilam Potrum Nannagar Keelakkarai, 1990

- Tamil Muslim identity. Hindu.com (2004-10-12). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- J.B.P.More (1 January 2004). Muslim Identity, Print Culture, and the Dravidian Factor in Tamil Nadu. Orient Blackswan. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-250-2632-7. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- Islamic Voice

- Irandaam Jaamangalin Kathai. Hindu.com. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- J.B.P.More (1 January 1997). Political Evolution of Muslims in Tamilnadu and Madras 1930–1947. Orient Blackswan. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-81-250-1192-7. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- Tamil Muslim Periyar Thatstamil.oneindia.in. Retrieved on 2012-06-27

- http://www.supremecourtofindia.nic.in/circular/senioradvocates.pdf

- Tamil Nadu / Chennai News : Indian National League State unit dissolved. The Hindu (2011-01-21). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- Susan Bayly, Saints, Goddesses and Kings — Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, Cambridge, 1989

- Biswas, Soutik. (2004-01-27) World's first Masjid for Women. BBC News. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- Pandey, Geeta. (2005-08-19) World | South Asia | Women battle on with mosque plan. BBC News. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- S.T.E.P.S.

- Taking on patriarchy

- "Kunnam constituency candidates list".

- "Aloor Shanavas at age 30".

Further reading

- Sinnappa Arasaratnam, Merchants, Companies and Commerce on the Coromandel Coast 1650 – 1740, New Delhi 1986

- Maritime India in the Seventeenth Century, New Delhi 1994

- Maritime Commerce and English Power (South East India), 1750 – 1800, New Delhi 1996

- Dutch East Indian Company and the Kingdom of Madura, 1650 – 1700, Tamil Culture, Vol. 1, 1963, pp. 48–74

- A Note on Periyathambi Marakkayar, 17th century Commercial Magnate, Tamil Culture, Vol. 10, No.1, 1964, pp. 1–7

- Indian Merchants and the Decline of Indian Mercantile Activity, the Coromandel case, The Calcutta Historical Journal, Vol. VII, No. 2/1983, pp. 27–43

- Commerce, Merchants and Entrepreneurship in Tamil Country in 18th century, paper presented in the 8th World Tamil Conference seminar, Thanjavur, 1995

External links

- TNTJ demands 10 percentage reservation for Muslims. The Hindu (2010-06-13). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.