Makuleke

The Makuleke Contractual Park or Pafuri Triangle constitutes the northernmost section of the Kruger National Park, South Africa, and comprises approximately 240 square kilometres of land.[2] The "triangle" is a wedge of land created by the confluence of the Limpopo and Luvuvhu Rivers at the tripoint Crook's Corner, which forms a border with Zimbabwe along the Limpopo River. It is a natural choke point for wildlife crossing from North to South and back, and forms a distinct ecological region.

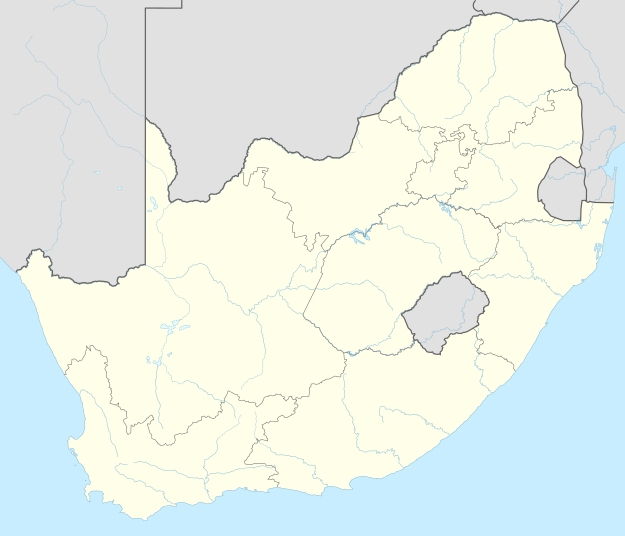

| Makuleke, Kruger National Park | |

|---|---|

Location in South Africa | |

| Location | Limpopo, South Africa |

| Nearest city | Tshipise, South Africa |

| Coordinates | 22°24′05″S 31°11′49″E |

| Area | 240 km2 (93 sq mi) |

| Established | Incorporated into Kruger Park 1969 Returned to Makuleke people 1998 |

| Governing body | South African National Parks and Makuleke People |

| Official name | Makuleke Wetlands |

| Designated | 22 May 2007 |

| Reference no. | 1687[1] |

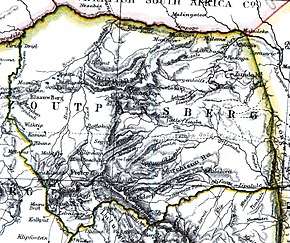

Pafuri (Tsonga) is derived from Mphaphuli, the dynastic name of Venda chieftains who ruled locally,[3] while the Luvuvhu River is named after a Combretum tree (Venda: muvuvhu, Tsonga Rivubye) growing on its banks.[4]

Geological history

The Makuleke region carries a remarkable geological and natural heritage that makes this region of interest to geographers and historians.[5][6] Some rocks in the area have been dated to over 250 million years old. In the bottom of Lanner Gorge are rocks that appear to be of Permian age, which indicate that the then interior of Pangea was harsh and arid.[7]

The rocks above the Permian ones are from the Triassic and date to between 248 million and 206 million years. Rocks of this age are found in the lower walls of Lanner Gorge and in these can be found fragments of bone and probably wood representing both holdovers from the Permian–Triassic extinction event like glossopetrids (a type of tree) and dicynodonts (a form of mammal-like reptile), and new forms that would dominate the Mesozoic, including modern conifers, cycads and of course dinosaurs, such as Euskelosaurus.[8]

Most of the sandstones in the Pafuri region however probably represent the great age of dinosaurs – the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. During the early parts of the Jurassic, which lasted from approximately 210 million years ago until about 144 million years ago, the area was almost certainly extremely arid as is evidenced by the great sandstones of the region and the many dune and desert structures – such as desert roses – that are found preserved within the rocks of the region.[7] In these sediments have been found the remains of early dinosaurs - possibly those of a species known as Massospondylus. It was also clearly a period of intense volcanism – with intrusive igneous rocks representing the ejected and intrusive molten matter from the interior of the Earth scattered about the region. The Jurassic was the age of great plant eating sauropods and smaller, carnivorous dinosaurs. This was the age of the origin of vertebrate flight with pterosaurs – flying dinosaurs – and the first birds appearing. The oceans themselves were full of a wide variety of life including many different types of fish, squids and ammonites – fossils of which are plentiful in the slightly younger rocks of the coastal regions to the southeast of the area. This was also a time of global upheaval as the World-continent of Pangea began to break up.

The Jurassic gives way to the Cretaceous Period in the upper rocks of the Makuleke area, and these are particularly evident in the North and East of the Pafuri triangle. In these upper-most rocks - the region still seems to be dominated by deserts but these seem to give way to water born gravels that may indicate the emergence of the ancient Limpopo in the region.[7] This is particularly evident in areas like Matule hill, where abundant gravels contain large and small bone fragments that appear to be those of medium-sized and small dinosaurs. Fossil wood typical of the Cretaceous flora have also been found in the rocks of the region. The Cretaceous Period lasted from about 144 million years ago until 66 million years when the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event occurred. While the Cretaceous is often referred to as the end of the age of dinosaurs, many new lifeforms appeared. This is the age of Tyrannosaurus rex and the ceratopsian dinosaurs (armoured and horned dinosaurs like Triceratops). The abundant marine deposits of the North East coast of South Africa are of this age. There is also the hope of finding the rarest forms of vertebrates alive in this time period – the tiny mammals which would eventually dominate the planet after the Cretaceous extinction event.[7]

The Cretaceous is followed by the Palaeogene Epoch – but this is apparently not well recorded in this region. The next sedimentary sequence is apparently just under two million years old – and comprises the Limpopo and Luvuvhu sands and gravels covering the lower parts of the region.[7] The landscape today in the Makuleke has been largely carved out by the meanderings and erosional activities of the two rivers. The sandy soils are sediments that have been brought from hundreds if not thousands of kilometers away by the Luvuvhu and the Limpopo.

Early human history

From about 1.5 million years ago, human ancestors, who were probably members of the species Homo erectus, were attracted to the area as a source of raw material for making early Stone Age tools.[7] The raw materials they were seeking are still visible today in the form of rocks and cobbles of non-native materials brought from the West and in abundance in channel lag deposits left by the ancient Limpopo. Homo erectus clearly found this raw material provided by the rivers of great importance and used these abundant gravel deposits as quarry sites – there are quite literally hundreds of thousands if not millions of stone tools, and the byproducts of their manufacturing process, which can be seen throughout the area.[7] Beautifully crafted hand axes – which are common – are evidence that this early stone tool culture represents the Acheulean industry and lasted from around 1.7 million years ago until around 250,000 years ago when it gave way to a slightly more advanced stone tool culture known as the Middle Stone Age. The vast numbers of Acheulean aged stone tools in the region are not only testimony of the large numbers of human ancestors that occupied the area, but also the vast amount of time in which this occupation occurred – more than 1.4 million years of continuous occupation.[7]

Tools of the Middle Stone Age are also in abundance in the area, particularly on top of hills and mountains in the region where these humans were apparently using overlooks and high spots to scout for game.[7] On top of many hills, at particularly good outlooks, can be found quite literally thousands of Middle Stone age knives, scrapers and spear-points. The Middle Stone Age begins around 250,000 years ago and ends around 25 – 35 thousand years ago. It holds within this temporal period not only the origins of a new and more complex toolkit used by humans, but the origin in Africa of modernity itself – it is during the middle part of this period that we see not only the emergence of the modern human brain and physical features but modern human culture – our infinite toolkit, artwork and burial of the dead.[9]

The Middle Stone age is followed in this region by the Latest Stone Age and most places have evidence of the micro-lithic cultures that characterize this hunter-gather lifestyle of modern humans.[7] The Latest Stone Age merges with the culture of Iron-aged Bantu speaking pastoralists who moved into the region around 1500 to 2000 years ago.[7][10] Rock art from this period is abundant in the region, particularly South of the Luvuvhu, but good examples have recently been discovered in the Pafuri region itself.[7]

Mapungubwe and the rise of Thulamela

From around 1200 a large cultural civilization and trade network began to emerge just to the North as is evidenced at such sites as Mapungubwe. Additionally, the idea of sacred leadership emerged – concept that transcends English terms such as "Kings" or "Queens".[11] Sacred leaders were elite members of the community, types of prophets, people with supernatural powers and the ability to predict the future. These early civilizations represented the rise of one of the greatest ancient trade networks the world has ever seen.[12][13]

Through interactions and trade with Muslim traders plying the Indian ocean as far south as present day Mozambique – the region emerged as a trade center producing gold and ivory and trading for glass beads and porcelain from as far away as China.[11][12]

The end of Mapungubwe occurred at the same time as the rise of an even greater trading and architectural civilization – that of Great Zimbabwe – which flourished for more than one hundred years. The centre of power then shifted to the south at a site known as Khami near present-day Bulawayo. It was then, around 1550, that groups crossed the Limpopo and founded numerous flourishing settlements in the Pafuri region including that of Thulamela on the southern bank of the Luvuvhu.[7] Thulamela was one of many walled cities that existed in the Pafuri triangle – almost every hill and overlook in the area has evidence of significant occupation during this period.[7] Thulamela and the other walled cities of the region were occupied at about the same time Portuguese trade began on the eastern coast of southern Africa.[11][12] The wealth and sophistication of these people is evident by the beautifully crafted gold jewelry, Arab glass beads and Chinese porcelain found in the sites and accompanying burials of sacred leaders.[11] The Thulamela culture ended around 1650.[14]

Political history

The Makuleke area was forcibly taken from the Makuleke people by the Apartheid South Africa government in 1969 and about 1500 of them were relocated to land to the South so that their original tribal areas could be integrated into the greater Kruger National Park.[5][15] In 1996 the Makuleke tribe submitted a land claim for 19,842 hectares (198.42 km2) in the northern park of the Kruger National Park.[16] The land was given back to the Makuleke people, however, they chose not to resettle on the land but to engage with the Private Sector to invest in tourism, thus resulting in the building of several game lodges.[17][18]

Reintroduction of game

Due to its proximity to Zimbabwe and Mozambique, the area had been heavily poached by the time the Makuleke people received the land back. Recent anti-poaching efforts and re-introduction of game including white rhino, have resulted in significant increases in the number of animals.[19]

The introduction of significant species which have been absent for many years (more than 120 years in the case of the white rhino), the protection of all animal and plant life, and partnering with the Makuleke people in sustainable ecotourism mark the beginning of the restoration of ecological integrity to the area.

Plants and animals

The Pafuri region is famous for its bird watching and more than 250 bird species have been recorded in a year. While comprising only about 1% of the Kruger National Park's actual area, the area contains plants and animals representing almost 75% of the Parks total diversity.[20]

The area has both semi-arid vegetation including numerous large baobabs as well as rich riverine forests with large nyala trees. While game is plentiful, one is most likely to encounter nyala, buffalo and bushbuck in the riverine areas and drier adapted game, including white rhino, in the uplands. The area is famous for its elephant herds in winter, which come to drink from the Luvuvhu River.[21]

Desertification

Many people visiting the modern Limpopo expecting the great grey-green greasy Limpopo of Kipling fame and yet seeing a great sand filled body instead. This is, however, a recent phenomenon, probably due to a great extent to the over utilization by agriculture of the water resources of the river. As recently as 1950, a Zambezi shark was caught at the confluence of the Luvuvhu and Limpopo rivers.[21]

Other facts

- Crook's Corner gained its name in the 19th century as the region was seen as a haven for criminals and poachers who would use the proximity of three countries at the join of the Limpopo and Luvuvhu rivers to escape police by fleeing out of their jurisdiction into an adjoining country.[22][23]

- The Makuleke area will form the core of the approximately 35,000 km² Transfrontier Park or "Peace Park".[17]

References

- "Makuleke Wetlands". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Wilderness Safaris (2007). "Pafuri Wilderness". Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- Bulpin, T. V. (1975). "The Kruger National Park". The Transvaal (A Collection of the Mobil Treasury of Travel Series covering the Transvaal). Cape Town: T. V. Bulpin. ISBN 0-949956-12-0.

- du Plessis, E.J. (1973). Suid-Afrikaanse berg- en riviername. Tafelberg-uitgewers, Cape Town. p. 265. ISBN 0-624-00273-X.

- Kruger National Park (2007). "Kruger History". Archived from the original on 1 January 2006. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- African adrenalin (2007). "Pafuri Camp". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- Berger, L.R. (2005). "the History of the Makuleke Concession" (PDF). Wilderness Safaris. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007.

- "Euskelosaurus Locations". 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- J. Shreeve (2006). "Human Journey". National Geographic. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- "Country Histories". 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- San Parks (2006). "Thulamela". Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- "Mapangubwe: History of Africa denied". 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- Wonders of the African World - PBS

- "The Thulamela Story". 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- Steenkamp, C. (2000). "The Makuleke Land Claim" (PDF). IIED Evaluating Eden Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011.

- "Commission on the Restitution of Land Rights, Media statement on a claim by the Makuleke Tribe on a Portion of the Kruger National Park and other areas". South African Commission on Restitution of Land Rights. 6 August 1996. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- Siyabona Africa (2007). "Pafuri Camp". Kruger Park. Archived from the original on 14 February 2007.

- Siyabona Africa (2007). "Outpost". Kruger Park.

- "Wilderness Trust". 2007. Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Kruger Park Lodges". 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- Hilton-Barber, B. & Berger, L.R. (2004). Exploring Kruger. Prime Origins Publishing. ISBN 0-620-31866-X.

- Rainbow Tours (2007). "Pafuri Camp". Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- San Parks (2006). "Pafuri Gate Fact Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2007.