Lord of the World

Lord of the World is a 1907 dystopian science fiction novel[1] by Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson that centres upon the reign of the Antichrist and the end of the world. It has been called prophetic by Dale Ahlquist, Joseph Pearce, Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis.[2]

| |

| Author | Robert Hugh Benson |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian novel, Christian novel |

| Publisher | Dodd, Mead and Company |

Publication date | 1908 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 352 pp |

Background

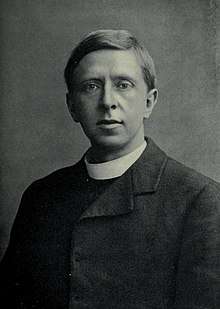

Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson, a former High Church Anglican Vicar, began writing Lord of the World two years after his conversion to Roman Catholicism rocked the Church of England in 1903.

The youngest son of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward White Benson, and the society hostess Mary Sidgwick Benson, Robert was descended from a very long line of Anglican clergymen. He had also read the litany at his father's 1896 funeral at Canterbury Cathedral and was widely expected to one day take his father's place as the most senior clergyman in the Anglican Communion. After a crisis of faith described in his 1913 memoir Confessions of a Convert, however, Benson was received into the Roman Catholic Church on September 11, 1903.[3]

According to Joseph Pearce, "The press made much of the story that the son of the former Archbishop of Canterbury had become a Catholic, and the revelation rocked the Anglican establishment in a way reminiscent of the days of the Oxford Movement and the conversion of Newman."[4]

The former Vicar found himself inundated with hate mail from Anglican clergy, men, women, and even children. Benson found himself accused of being "a deliberate traitor", "an infatuated fool", and of bringing dishonor upon his father's name and memory. Although he replied scrupulously to every letter, Benson was deeply hurt. He later wrote that he received considerable solace in the words that an Anglican Bishop had spoken to his mother, "Remember that he has followed his conscience after all, and what else could his father wish for him than that?"[5]

After his ordination as a Catholic priest at Rome in 1904, Fr. Benson had been assigned as a Catholic Chaplain at Cambridge University. It was during his stay at Cambridge Rectory that Lord of the World was conceived and written.

Inception

According to his biographer Fr. Cyril Martindale, the idea of a novel about the Antichrist was first suggested to Fr. Benson by his friend and literary mentor Frederick Rolfe in December 1905. It was Rolfe who also introduced Mgr. Benson to the writings of the French Utopian Socialist Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon.

According to Fr. Martindale, as Benson read Saint-Simon's writings, "A vision of a dechristianised civilisation, sprung from the wrecking of the old régime, arose before him and he listened to Mr. Rolfe's suggestion that he should write a book on Antichrist."[6]

Writing during the pontificate of Pope Pius X and prior to the First World War, Monsignor Benson accurately predicted interstate highways, weapons of mass destruction, the use of aircraft to drop bombs on both military and civilian targets, and passenger air travel in advanced Zeppelins called "Volors". Writing in 1916, Fr. Martindale compared Mgr. Benson's ideas for future technology with those of legendary French science fiction novelist Jules Verne.[7]

However, Mgr. Benson also presumed the survival of European colonialism in Africa, the continued expansion of Imperial Japan, and that predominant travel would continue to be by railway. Like many other Catholics of the era in which he wrote, Monsignor Benson believed in Masonic conspiracy theories and shared the political and economic views of G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc.

Synopsis

Prologue

In early 21st century London, two priests, the white-haired Father Percy Franklin and the younger Father John Francis, are visiting the subterranean lodgings of the elderly Mr. Templeton. A Catholic and former Conservative Member of Parliament who witnessed the marginalization of his religion and the destruction of his party, Mr. Templeton describes to the two priests the last century of British and world history.

Since the Labour Party took control of the British Government in 1917, the British Empire has been a single party state. The British Royal Family has been deposed, the House of Lords has been abolished, Oxford and Cambridge have been closed down, and all their professors sent into internal exile in Ireland. Marxism, atheism, and secular humanism, which Templeton describes as the tools of Freemasonry,[8] dominate culture and politics. The Anglican Communion has been disestablished since 1929 and, like all forms of Protestantism, is almost extinct. The world now has only three main religious forces: Catholicism, secular humanism, and "the Eastern religions".[9]

Nationalism has been destroyed by Marxist internationalism and the world has been divided into three power-blocs. The first, which is generally marked in red on maps, is a European Confederation of Marxist one-party states and their colonies in Africa that use Esperanto for a world language. The second, marked in yellow, is "the Eastern Empire", whose Emperor, the "Son of Heaven", descends from the Japanese and Chinese Imperial Families. The third, the blue marked, "the American Republic", consists of North, South, and Central America.

In a move that almost toppled Marxism in the Confederation during the 1970s and '80s, the Eastern Empire invaded, annexed, and now rules India, Australia, and New Zealand, as well as all of Russia east of the Ural Mountains. For this and other reasons, Mr. Templeton explains, the Confederation and the Eastern Empire are now on the brink of a global war.[10]

After Mr. Templeton completes his story, Fathers Franklin and Francis return to their spartan apartments at Westminster Cathedral.

Book I: The Advent

_Ramsay_MacDonald_by_Solomon_Joseph_Solomon.jpg)

Oliver Brand, an influential Labour MP from Croydon, listens as his secretary, Mr. Phillips, describes the seemingly inevitable rush toward war between Europe and the Eastern Empire. He mentions that a mysterious Senator Felsenburgh has unexpectedly taken charge of the American Republic's peace delegation. Felsenburgh is tirelessly crisscrossing the Empire, delivering speeches to rapt audiences. The Senator shows a remarkable fluency in the languages of his listeners.

In conversation with his wife, Mabel, Oliver comments that war between Europe and the Empire will be "Armageddon with a vengeance", and expresses hope that Senator Felsenburgh will save the day. Although Mabel Brand appears concerned, her husband responds, "My dear, you must not be downhearted. It may pass as it all passed before. It is a great thing that we are listening to America at all. And this Mr. Felsenburgh seems to be on the right side."[11]

Over breakfast, Oliver frets about his upcoming trip to Birmingham, where the outraged population is again demanding the right to trade freely with the American Republic. As his mind returns to the possible war against the Empire, Brand ponders that the real problem is the survival of religious belief in the Eastern Empire—Buddhism, Islam, Sufism, Confucianism, and Pantheism. In Great Britain, only Catholicism remains in "a few darkened churches" and "with hysterical sentimentality" in Westminster Cathedral. He ponders with disgust how, against his opposition, Ireland was granted Home Rule and "opted for Catholicism." Furthermore, the city of Rome was "given up wholly" in exchange for all church property in Italy to Pope John XXIV, who has transformed it into a Hong Kong-style enclave where "mediaeval darkness" reigns supreme. He recalls with outrage how the Italian Republic moved its capital to Turin. As he departs to catch a volor to Birmingham, Oliver looks out at "the grey haze of London, really beautiful, this vast hive of men and women who had learned at least the primary lesson of the gospel that there was no God but man, no priest but the politician, and no prophet but the schoolmaster."[12]

As she prepares to board a train to Brighton, Mabel Brand witnesses a Government volor crash into the station. As the Government's Ministers of Euthanasia arrive and begin to finish off the wounded, maimed and dying, Mrs. Brand witnesses Father Percy Franklin arrive. She is stunned to see the priest open his coat, pull out his crucifix and give the Last Rites to the dying Catholic lying next to her. After she returns home, deeply moved and traumatized by what she has witnessed, Mabel tells Oliver that both Father Franklin and the dying man seemed to believe in what they were doing.

While deeply grieved that his wife has witnessed the horrors of the accident, Oliver explains Catholic doctrine about the Afterlife, which he mocks as a ridiculous belief that a person's mind can survive despite their brain being dead. According to Brand, for Father Franklin, the soul of the man is either "in a sort of smelting works being burned", or if "that piece of wood took effect" he is "somewhere beyond the clouds" with the Holy Trinity, the Mother of God, and the Communion of Saints. He explains that "that kind of thing may be nice, but it isn't true." Impressed by her husband's explanation of the fallacy of religion, Mabel relaxes.[13]

At the residence of the Cardinal-Protector near Westminster Cathedral, Father Percy Franklin finishes writing his Latin language report to Rome about the mass defections taking place among English Catholics and the recent conversions from the crumbling Anglican Communion. As he walks toward the elevator, Father Franklin finds that Father John Francis, whom he has been attempting to nurse through his mounting doubts, has lost his faith and decided to leave the priesthood. In a last-ditch effort to prevent this, Father Franklin explains that Christianity "may be untrue", but it cannot be absurd and false as long as educated and intelligent people continue to believe in its teachings. Unmoved, Father Francis rebuffs Father Franklin's argument and, with bottomless self-pity, asks whether they can remain friends. Father Franklin responds, "What kind of friends could we be?" An infuriated Fr. Francis leaves in a huff.[14]

After saying his prayers before the Eucharist in the Tabernacle, Father Franklin joins his fellow priests as they discuss Felsenburgh over dinner. Later, as he ponders the disintegration of Catholicism throughout the world, Father Franklin decides that what the Church needs most is a new religious order, which will help the Faith to survive and spread in the catacombs.[15]

While giving a speech at Trafalgar Square (now with Nelson's Column replaced with statues of prominent socialists), Oliver Brand is wounded in the arm by a Catholic layman armed with a pistol. After the would-be assassin is beaten to death by the assembled crowd, Oliver informs Mabel of the news. Senator Felsenburgh is crisscrossing the East delivering multiple speeches, possibly on the behalf of the Emperor, trying to disperse the warmongering Eastern Convention (vaguely associated with the Sufis). Even so, Oliver explains that he must travel to Paris to prepare armaments for expected war. He explains that an explosives manufacturer named Benninschein has developed weapons of mass destruction and sold them to both power blocs. Therefore, a war will leave at least one power bloc completely annihilated.[16]

Hours later, a glowing Oliver returns from Paris and tells Mabel that, due to Felsenburgh, all chances of war have evaporated. It will soon be announced, and Oliver urges Mabel to come with him at once. Felsenburgh, he explains, will be there.[17]

As the Brands depart for their meeting with Felsenburgh, Oliver's secretary, Mr. Phillips arrives at the flat of Father Percy Franklin. Explaining that Oliver Brand's elderly mother used to be a Catholic, Phillips explains that she wishes to return to the Church before her imminent death. Although he knows it might be a setup, Father Franklin feels that he cannot refuse. After having what he expects to be his last Confession heard, he walks to London Victoria Station to catch a train to Croydon. To his shock, Father Franklin encounters cheering crowds and electrified letters announcing the dispersal of the Eastern Convention, the calling off of the expected war, the establishment of "universal brotherhood", and Felsenburgh's imminent arrival in London. After secretly arriving at the Brands' home, Fr. Franklin is met by Mrs. Brand and, realizing that she is completely sincere, he receives her back into the Catholic Church.[18]

The Brands return home an hour earlier than expected. Enraged that a priest would visit his home, Oliver is utterly infuriated that his mother would actually request such a thing. Despite his outraged demands, Father Franklin refuses to reveal who acted as the go-between. To Oliver's shock, Mabel urges Father Franklin to leave in peace. She explains that he will see Felsenburgh and the overflowing joy that his arrival has occasioned in England. This is why, Mabel explains, she is no longer afraid of him or of others like him. Deeply surprised that he will not be arrested, Father Franklin leaves into the summer night.[19]

As he returns to Victoria Station, Father Franklin encounters a rally being addressed by Senator Felsenburgh. For a brief moment, the Senator's hypnotic powers of persuasion cause the priest to believe in him, but Father Franklin's doubts about the Catholic Faith are soon overcome.[20]

Book II: The Encounter

As Oliver Brand reads Mabel an account of Felsenburgh's arrival in England in the Marxist newspaper New People, it is revealed that the Senator, who speaks all languages with equal fluency, has been hailed as the Mahdi throughout the Islamic World. It boasts that his background has nothing "that convicts him of sin", in contrast to the corrupt practices that have "made the sister continent what she is today".[21]

It adds, however, "Of his actual words we have nothing to say. So far as we are aware, no reporter made notes at the moment; but the speech, delivered in Esperanto, was a very simple one; and very short. It consisted of a brief announcement of the great fact of Universal Brotherhood, a congratulation to all who were yet as live to witness this consummation of history; and at the end, an ascription of praise to the Spirit of the World whose incarnation was now accomplished."[22]

The article proceeds to mock the supernatural as dead. It announces that a new and enlightened age has come and that mankind is finally ready for world peace.[23]

Meanwhile, as her son is away with Felsenburgh, Mrs. Brand takes a sudden turn for the worse. Ignoring Mabel's sermons about how Christianity has divided the human race and caused nothing but terrible violence, Mrs. Brand pleads for Father Franklin to be summoned. When Oliver returns home that day, a weeping Mabel informs him that his mother died an hour before. Clutching her rosary, Mrs. Brand had continued to scream for a priest as long as she was able to speak. Mabel explains, however, that she had had her mother-in-law involuntarily euthanised, knowing that her husband would desire it. Although moved to tears by his mother's passing, Oliver tells Mabel that she did the right thing.[24]

Meanwhile, Father Franklin, who has been summoned to Rome by Pope John XXIV, arrives in Paris to board a volor connection to Italy. As he waits at the main volor station in the former Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Montmartre, Father Franklin ponders how the England that he is leaving behind is beginning to resemble an earthly Hell. Upon his arrival in Rome, Father Franklin is greeted by the Cardinal Protector of England and informed that the Pope will receive him at eleven o'clock.[25]

Upon being shown into the presence of His Holiness, Father Franklin explains his ideas for the Church's survival under the rule of Julian Felsenburgh. The answer must be increasing standardization and centralization. After recounting the previous steps taken towards centralization, such as the forced merging of all religious orders, the abolition of the Eastern Catholic Churches, and the forced residence of all members of the College of Cardinals in Rome, Father Franklin recommends that violence must never be used – the Mass and the rosary must be the primary weapon against the coming persecution.[26] In conclusion, Father Franklin recommends the forming of a new religious order, with no habit or badge, "freer than the Jesuits, poorer than the Franciscans, more mortified than the Carthusians: men and women alike – the three vows for their Church; each Bishop responsible for their sustenance; a lieutenant in each country.... And Christ Crucified for their patron."[27]

After the audience, Father Franklin is assigned as an assistant to the ailing Cardinal Protector of England. His duties are to offer daily Mass in the Cardinal's Oratory and to read and summarize all reports from England. During his free hours, Father Franklin takes long walks through the city. He ponders how the Eternal City, which the Pope has divided into four national quarters, now represents a microcosm of the world.[28]

Towards the end of August, as Father Franklin walks toward the celebration of the Pope's Name Day – significantly, the Pope is named John, so the feast in question is the rather unusual choice of the Decapitation, not the more popular Nativity, of St. John the Baptist -, he passes the yoked carriages of the deposed Crowned Heads of Europe. As he recognizes the British Royal Family, the German House of Hohenzollern, the House of Romanov, the Spanish and French Houses of Bourbon, and scores of "lesser powers", Father Franklin ponders the "appalling danger" their presence constitutes "in a democratic world." The world, he knows, affects "to laugh at the desperate play-acting of Divine Right on the part of fallen and despised families", but he shudders to think what could happen if that sentiment ever turns to anger.[29]

Half an hour later, Father Franklin follows the Pope in a procession through the streets of Rome and ponders the contrast between the Church and the World. "The two Cities of Augustine lay for him to choose. The one was that of a world self-originated, self-organized and self sufficient, interpreted by such men as Marx and Herve, socialists, materialists, and, in the end, hedonists, summed up at last by Felsenburgh. The other lay displayed in the sight he saw before him, telling of a Creator and of a creation, of a Divine purpose, a redemption, and a world transcendent and eternal from which all sprang and moved. Of the two, John and Julian, was the Vicar, and the other the Ape, of God... And Percy's heart in one more spasm of conviction made its choice..."[30]

As the Pope, the College of Cardinals, and the deposed royals assemble in the Vatican, Father Franklin's heart quickens as he watches the Papal Mass that follows, in which the former monarchs serve the Pope at the Altar.[31]

As Pope John Elevates the Host, Father Franklin ponders that here lies the one hope of the world's dwindling Catholics, "as mighty and little as once within the manger. There was none other that fought for them but only God." He realizes that if God cannot be moved from His silence by the persecution of the Faithful, how could He not respond to the reenactment of His Son's Passion and Death, which pleads now within an "island of Faith amid a sea of laughter and hatred"?[32]

After the Mass, as an exhausted Father Franklin finally sits down, the heartbroken Cardinal-Protector of England arrives and informs him that Julian Felsenburgh is now President of Europe. As they examine the dispatches late into the night, it soon becomes clear that the news is true. After each of the Great Powers offered him the Presidency and was repeatedly refused, a Convention of Powers offered Felsenburgh a unified proposal. Felsenburgh was to "assume a position hitherto undreamed of in democracy"—a House of Government in every Capital, a final veto lasting three years on every motion submitted to him, legal power granted to every motion he submits on three consecutive years, and the title President of Europe.[33]

The narration reads, "...all this, Percy saw very well, involved the danger of a unified Europe increased tenfold. It involved all of the stupendous force of Socialism directed by a brilliant individual. It was a combination of the strongest characteristics of the two methods of Government. The offer had been accepted by Felsenburgh after eight hours silence."[33]

Tossing and turning through a sleepless night, Father Franklin ponders "the madness that had seized upon the nations; the amazing stories that had poured in that day of the men in Paris, Who, raving like Bacchantes, had stripped themselves naked in the Place de la Concorde, and stabbed themselves to the heart, crying to thunders of applause that life was too enthralling to be endured... of the crucifixion of the Catholics that morning in the Pyrenees, and the apostasy of three bishops in Germany..." Heartsick, Father Franklin ponders how God can make no sign and speak no word.[34]

As morning breaks, the Cardinal-Protector arrives and announces that he is terminally ill. When he dies, Pope John has decided that it will be Father Franklin who will succeed him.

The following day, Father Franklin arrives for a Papal Allocution. Fully expecting Pope John to issue another Anathema against both Marxism and Freemasonry—the ideological pillars of Felsenburgh's new order— Father Franklin silently laments that the world will simply ignore it. Instead, he is stunned as the Pope instead announces that he is creating an Order of Christ Crucified to spread the Faith in the face of persecution.[35]

Meanwhile, President Felsenburgh has instructed the Parliaments of Europe to institute weekly Humanist ceremonies, inspired by the rituals of Freemasonry,[36] in all the cathedrals and churches which are not in Catholic hands. Attendance is to be optional except for the four annual festivals of Maternity, Life, Sustenance, and Paternity. Those who refuse to attend are threatened with dire consequences.[37]

As Oliver Brand, now Minister of Public Worship,[38] plans the upcoming festival of the Maternity with ex-priest John Francis, he learns to his dismay that the Cardinal-Protector of England has died and that Father Percy Franklin has taken his place.[39] In conversation with Mabel, Oliver expresses contempt for the Pope's new religious order and calls it the most foolish thing that the Catholic Church could ever have done.[40]

Meanwhile, in Rome, Cardinal Franklin arrives at his offices and reads reports of the new Humanist rituals. He recalls with dismay that John Francis was only recently offering the Mass at Catholic Altars. He ponders that Felsenburgh's rituals are "Positivism of a kind, Catholicism without Christianity, Humanity worship without its inadequacy."[41]

With a deep sense of pessimism, the Cardinal recalls the outrage which these decrees have caused among the world's Catholics and how, in a recent Audience, he and Cardinal Hans Steinmann of Germany urged Pope John to issue "a stringent decree... forbidding acts of violence on the part of Catholics." The faithful are to be encouraged to be patient, to quietly avoid Humanist worship, to say nothing unless arrested and questioned, and to gladly suffer persecution for Christ's sake.[42] As the Pope considers their proposal, Cardinal Franklin learns that Mr. Phillips—Oliver Brand's now disgraced Secretary—urgently wishes to see him. He gives orders that Mr. Phillips is to arrive in January.[43]

As Advent proceeds to Christmas, Cardinal Franklin witnesses the new Order of Christ Crucified go forward "with almost miraculous success." Practically the entirety of Rome has enrolled, including the deposed monarchs. From throughout the world, long lists arrive of new members drawn up by their Bishops,[44] "...but better than all this was the tidings of victory in another sphere. In Paris forty of the new-born Order had been burned alive in one day in the Latin Quarter, before the Government intervened. From Spain, Holland, and Russia had come in other names. In Düsseldorf, eighteen men and boys, taken by surprise at the singing of Prime in the Church of St. Lawrence, had been cast down one by one into the city sewer, each chanting as he vanished: Christi Fili Dei vivi miserere nobis, and from the darkness had come the same broken song until it was silenced with stones. Meanwhile, German prisons were thronged with the first batches of recusants. The world shrugged its shoulders, and declared that they had brought it on themselves, while it yet deprecated mob violence, and requested the attention of the authorities and the decisive repression of this new conspiracy of superstition. And within St. Peter's Church the workmen were busy at the long rows of new altars, affixing to the stone diptychs the brass-forged names of those who had already fulfilled their vows and gained their crowns. It was the first word of God's reply to the world's challenge."[45]

When Mr. Phillips arrives in Rome on New Year's Day, his news horrifies Cardinal Franklin—English and German Catholics are plotting a suicide bombing against the Abbey where Felsenburgh's inner circle meets. Cardinal Franklin informs Pope John, who immediately dispatches him and the Cardinal Steinmann of Germany, to their respective homelands to try to prevent the bombing. As their volor flies over the Alps, the two Cardinals encounter an enormous squadron of volors heading south from England and Germany. Having also learned of the plot through Mr. Phillips, President Felsenburgh has ordered the Dresden-style destruction of Rome in retaliation.[46]

Using Benninschein's new explosives, the Anglo-German volors systematically firebomb the entire city of Rome, killing Pope John, all the assembled Cardinals, and countless unarmed men, women, and children. Meanwhile, news of the plot triggers anti-Christian pogroms to spread throughout the world. In London, Mabel Brand witnesses mobs of militant Atheists crucifying Christian men, women, and children and lynching priests before her very doors. Having believed that only religious belief could incite such violence, Mabel's faith in Felsenburgh is left deeply shaken.

Upon his return home, Oliver Brand attempts to console his wife. He explains that the pogrom has happened because the people of England have not yet been purged from the residue of Christianity. When Mabel asks why the riots were not obstructed by the police, however, Brand admits that the police have been ordered to stand down. Although she admits that she has been contemplating suicide, Mabel relaxes when informed that Felsenburgh will soon be arriving. Oliver reminds her, ominously, that it is over. Rome has already been destroyed and that he co-signed the orders. Devastated, Mabel dissolves in tears.[47]

The following day, Oliver Brand reads news reports of the riots. According to the Marxist newspaper New People, Westminster Cathedral has been sacked and every altar overthrown. A priest managed to consume the Eucharist moments before being seized and throttled. The Archbishop, two bishops, and eleven priests have been lynched in the sanctuary. Thirty-five convents have been destroyed and St George's Cathedral, Southwark, has been burned to the ground. It is alleged that for the first time since the introduction of Christianity to England that there is not a single functioning church.[48]

That afternoon, the Brands and all the people of London enter St. Paul's Cathedral for the Feast of Maternity, over which Felsenburgh will preside. After procession with incense and a few opening remarks by turncoat Mr. John Francis, Felsenburgh enters the Cathedral dressed in the red and black robes of a British High Court judge. As the crowd listens with rapt admiration, Felsenburgh speaks of the destruction of Rome and the recent pogroms against Christians. He explains that future generations of men must flush with shame to remember that mankind had once turned its back on the risen light.

Then, a curtain is torn aside, revealing a statue of a naked mother and child. Felsenburgh leads all the assembled worshipers in prayer to the "Mother of us all." All those present hail the statue as Queen and Mother. The chapter ends with the words, "Then in the heavenly light, to the crash of drums, above the screaming of the women and the battering of feet, in one thunder peal of worship ten thousand voices hailed Him Lord and God."[49]

Book III: The Victory

After the destruction of Rome, Cardinals Franklin and Steinmann traveled to the deathbed of the only other survivor of the College of Cardinals — the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. They held an impromptu Papal Conclave, which resulted in the election of Cardinal Franklin as Pope Sylvester III.[50] Soon after, the Latin Patriarch died and Cardinal Steinmann returned to Berlin, where he was promptly lynched.

Pope Sylvester has since reorganized the Church so that it will survive the global persecution under Felsenburgh's Government. He has secretly rebuilt the College of Cardinals, but his actual name and location (Nazareth) are known only to the members of the College.

Meanwhile, Felsenburgh has ordered the Test Act — all the world's people must either formally disavow the existence of God or be executed without trial. While large numbers of religious believers refuse and are slaughtered, many others agree without any qualms. Mr Philipps, who states that he cannot disavow the existence of God and cannot either confess to Him, is granted a week to make up his mind.

With the last remnant of her faith shattered, Mabel Brand secretly leaves her husband and checks into a voluntary euthanasia clinic. All of Oliver's attempts to find her are in vain. After the eight-day waiting period required by law, Mabel writes a suicide letter to her husband and voluntarily suffocates herself using a provided gas mask. As her life fades away, Mabel finds, "something resembling sound or light, something she knew in an instant to be unique, tear across her vision. Then she saw, and understood..."[51]

Due to an informer—Cardinal Dolgorovski of Moscow—the President has learned of the new Pope and his plans for a secret meeting of remaining Cardinals in Nazareth. The President demands the British Cabinet to join in a volor-bombing attack to wipe out the Church, while allowing the inhabitants of the village to escape. He further suggests that Cardinal Dolgorovski should be executed to prevent him from "relapse" and taking over the remnants of the Roman Catholic Church. Oliver Brand and the Cabinet give the President their unanimous assent.

In Nazareth, Pope Sylvester is told that Cardinal Dolgorovski has refused a direct order to attend. He realizes that Dolgorovski has been turned and that Nazareth is about to be destroyed. He gives orders to warn the city's residents to flee and then offers Mass followed by Eucharistic Adoration.

As Felsenburgh personally flies in the volor-squadron, the narration states, "He was coming now, swifter than ever, the heir of temporal ages and exile of eternity, the final piteous Prince of rebels, the creature against God, blinder than the sun which paled and the earth which shook; and, as He came, passing even then through the last material stage to the thinness of a spirit fabric, the floating circle swirled behind Him, tossing like phantom birds in the wake of a phantom ship.... He was coming, and the earth, rent once again in its allegiance, shrank and reeled in the agony of divided homage...."[52]

As volor firebombs begin to rain down on Nazareth, Pope Sylvester and the Cardinals calmly continue to chant the Pange Lingua before a Host exposed in a Monstrance on the altar. The last words of the novel are: "Then this world passed, and the glory of it."[53] (Sic transit gloria mundi).

Influences

Monsignor Benson drew upon history, other works of science fiction, and current events to create a fictional universe.

Literature

Frederick Rolfe's anti-Modernist satirical novel Hadrian VII inspired numerous aspects of Lord of the World, including the introductory first chapter.[54]

According to his biographer, Fr. Cyril Martindale, Mgr. Benson's depiction of the future was in many ways an inversion of the science fiction novels of H. G. Wells.[55] Like many other Christians of the era, Benson was sickened by Wells' belief that Atheism, Marxism, World Government, and Eugenics would lead to an earthly utopia. Due to his depiction of a Wellsian future as a murderous global police state, Benson's novel has been called one of the first modern works of dystopian science fiction.

History

A further source of inspiration was Mgr. Benson's interest in history.

Fr. Percy Franklin's constant fear of arrest while carrying out his priestly ministry in London is inspired by Mgr. Benson's research into the aftermath of the English Reformation. Fr. Franklin's suspicion that Fr. Francis may have become a police informant and his belief that Mrs. Brand's request for a priest is a trap to ensnare him are reminiscent of the tactics used by Elizabethan Era priest hunters like Sir Richard Topcliffe.

Julian Felsenburgh's leadership style was modeled after that of Napoleon Bonaparte, whose mistakes he was intended to correct. In one of the three notebooks he kept while writing Lord of the World, Mgr. Benson wrote that while Napoleon's weakness was "his soft heart: he forgave," Felsenburgh, "never forgives: for political crime he strips of position, making the man incapable of holding office; for treachery to himself he drops them out of his councils." He further described the Anti-Christ as "complete hardness, and kindness".[54]

The number of former priests and bishops who reject Catholicism are inspired by the priests who took an oath rejecting the authority of the Holy See following the French Revolution. All were excommunicated by the Pope and became employees of the French Government following the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

The word, "Recusants", which Fr. Franklin uses to describe Catholics who absent themselves from compulsory Humanist worship, dates from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England. The word was originally used to describe both Catholics and Puritans who, despite heavy fines and imprisonment, refused to attend weekly Anglican services.

The conspiracy to suicide bomb President Felsenburgh and its grisly aftermath are inspired by the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in which a small group of English Catholic noblemen led by Robert Catesby planned to blow up King James I of England during an address before Parliament. Like its fictional counterpart, the Gunpowder Plot was exploited for propaganda and used to justify a campaign to completely and permanently destroy Roman Catholicism.

The scene in which President Julian Felsenburgh leads an enormous congregation in the worship of a mother goddess inside St. Paul's Cathedral is inspired by the worship of the Goddess of Reason inside Notre Dame Cathedral during the Reign of Terror.

As acknowledged in the text, the character of Cardinal Dolgorovski of Moscow is inspired by Judas Iscariot.[56][57]

The word Test Act for Felsenburgh's legislative means to root out Catholicism is no invention of his or of his author, but there actually have been Test Acts in England.

Current events

Further inspiration was gleaned from Mgr. Benson's following of current events.

The fear among Europeans of the Eastern Empire and its ruler, the Son of Heaven, is inspired by the shock that greeted the territorial expansion of the Japanese Empire before, during, and after the Russo-Japanese War.

The dystopian Marxist Government of Britain is inspired by the events of the British general election of 1906. Prior to the election, a large number of small Marxist political parties consolidated to form a unified bloc called the Labour Party, which won 29 seats in the House of Commons. The first chapter, which describes the overthrow of the British royal family, the abolition of the House of Lords, the disestablishment of the Church of England, and the closing of the universities is inspired by the Labour Party's platform at the time the novel was written.

The Marxist uprising that topples the Son of Heaven is inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1905, which Mgr. Benson was following in the newspapers.

Julian Felsenburgh's sermon at St. Paul's and the emotional reaction of his listeners are inspired by press reports of the Reverend Evan Roberts and the 1904-1905 Welsh Revival. Rev. Roberts was similarly able to provoke public displays of emotion in his listeners and is regarded as the inventor of Pentecostalism. He was also the focus of a cult of personality which scandalized more traditional churches. At the height of his ministry, Rev. Roberts' denunciations of literary and cultural societies, competitive sports, and alcohol consumption temporarily caused a sea change in Welsh culture. Countless rugby teams and literary societies were voluntarily disbanded. In Welsh coal mining towns, pubs closed down for lack of business and the National Eisteddfod of Wales was almost deserted. Rev. Roberts, however, eventually came to believe that his ministry was not of God, voluntarily left the public eye, and spent the remaining years of his life resisting efforts to draw him back to the revival circuit. He died, a virtual recluse, in 1951.

The Anti-Catholic riots that follow the discovery of the planned suicide bombing are inspired by Anti-Jewish Pogroms in the Russian Empire, which also took place with the collusion of senior Government officials and policemen.

Composition

Benson first mentioned his ideas in a letter to his mother on 16 December 1905, "Yes, Russia is ghastly. Which reminds me that I have an idea for a book so vast and tremendous that I daren't think about it. Have you ever heard of Saint-Simon? Well, mix up Saint-Simon, Russia breaking loose, Napoleon, Evan Roberts, the Pope and Antichrist; and see if any idea suggests itself. But I'm afraid it is too big. I should like to form a syndicate on it, but that is an idea, I have no doubt at all."[58]

In a letter to Mr. Rolfe on 19 January 1906, Benson wrote, "Anti-Christ is beginning to obsess me. If it is ever written, it will be a BOOK. How much do you know about the Freemasons? Socialism? I am going to avoid scientific developments, and confine myself to social. This election seems to hold vast possibilities in the direction of Anti-Christ's Incarnation – I think he will be born of a virgin. Oh! If I dare to write all that I think! In any case, it will take years."[59]

According to Father Martindale, the gradual evolution of Lord of the World can be charted through three of Monsignor Benson's notebooks. The first two reveal that Benson based the physical appearances of Fr. Percy Franklin and President Julian Felsenburgh on "a rather prominent socialist politician" whose name Father Martindale does not disclose.[60] Mgr. Benson's notebooks also reveal that Pope Sylvester was originally "made to take refuge and confront Antichrist in Ireland."[61]

On 16 May 1906, Benson wrote in his diary, "Anti-Christ is going forward; and Rome is about to be destroyed. Oh, it is hard to keep it up! It seems to me that I am getting terser and terser until finally the entire story will end in a gap, like a stream disappearing in sand. It is such a fearful lot that one might say, that every word seems irrelevant."[62]

On 28 June 1906, Benson again wrote in his diary, "I HAVE FINISHED ANTI-CHRIST. And really there is no more to be said. Of course I am nervous about the last chapter – it is what one may call just a trifle ambitious to describe the End of the World. (No!) But it has been done."[63]

In a 28 January 1907 letter, Lord of the World was praised by Frederick Rolfe. Commenting on Benson's decision to satirize him as "Chris Dell" in The Sentimentalists, Rolfe wrote, "You are worrying yourself most unnecessarily about me, I assure you... I am laughing at the absurdity of the whole thing though I must confess that I was rather amazed when I heard that everybody recognized me in Chris. It was rather a blow to my amour propre... You will, I hope, reap a rich harvest of shekels from the transaction, and the world will forget The Sentimentalists when it stands wondering before The Lord of the World."[64]

Textual error in modern editions

Most modern editions of Lord of the World contain an error in Book III, Chapter Five, Section III, carried forward from a printer's error in the American edition of the book. A sentence in the second paragraph of Section III began as follows, in the British first edition:

“In short, it seemed that he could do no good by remaining in England, and the temptation to be present at the final act of justice in the East by which those who had indirectly been the cause of his tragedy were to be wiped out…”

In the corrupted text found in most modern editions, the passage reads (erroneous portion in italics):

"In short, it seemed that he could do no good by remaining in England, and the temptation to be present at the final act of justice in the East by which land, and, in fact, it was more than likely that if she were to be wiped out…”

Release and reception

Upon its 1907 publication, Lord of the World caused an enormous stir among Catholics, non-Catholics, and even among non-Christians. Mgr. Benson was therefore kept busy answering letters from both readers and literary critics. Mgr. Benson's reading of these letters helped inspire his novel The Dawn of All.

In reply to a critic who expressed a belief that Mabel Brand condemned herself to Hell by committing suicide, Mgr. Benson wrote, "I think Mabel was alright, really. Honestly, she had no idea that suicide was a sin; and she did pray as well as she knew how at the end."[65]

In a 16 December 1907 letter to Mgr. Benson's brother, British physicist Sir Oliver Lodge wrote, "The assumption that there can be no religion except a grotesque return to Paganism, short of admitting the supremacy of Mediaeval Rome, is an unexpected contention to find in a modern book... I am wondering what the leaders of the Church think of it. Perhaps Pius X may approve; but it is difficult to suppose that it can meet with general approbation. If it does, it is very instructive."[66]

Some critics and readers misinterpreted the novel's last sentence as meaning, "the destruction, not of the world, but of the Church." Some Marxists were reportedly "delighted" by the ending and one non-Catholic reader wrote that Lord of the World had, "struck heaven out of my sky, and I don't know how to get it back again."[67]

Other readers were more admiring. Although "grave exception" was taken there to Mgr. Benson's "sympathetic treatment" of Mabel Brand's suicide, Lord of the World was enthusiastically received in France.[68]

In a letter to Mgr. Benson, Jesuit priest Fr. Joseph Rickaby wrote, "I have long thought that Antichrist would be no monster, but a most charming, decorous, attractive person, exactly your Felsenburgh. This is what the enemy has wanted, something to counteract the sweetness of Christmas, Good Friday, and Corpus Christi, which is the strength of Christianity. The abstruseness of Modernism, the emptiness of Absolutism, the farce of Humanitarianism, the bleakness (so felt by Huxley and Oliver Lodge) of sheer physical science, that is what your Antichrist makes up for. He is, as you have made him, the perfection of the Natural, away from and in antithesis to God and His Christ.... As Newman says, a man may be near death and yet not die, but still the alarms of his friends are each time justified and are finally fulfilled; so of the approach of Antichrist."[69]

Shortly after Mgr. Benson's novel was published, British historian and future Catholic convert Christopher Dawson paid a visit to Imperial Germany. While there, Dawson witnessed the increasing de-Christianisation of German culture and the rapid growth of the Marxist Social Democratic Party. In response, Dawson called the Kaiser's Germany "a most soul-destroying place", and complained that German intellectuals, "examine Christianity as if it were a kind of beetle." Dawson further lamented that his stay in that "most dreadful" country reminded him of "the state of society in Lord of the World."[70]

Furthermore, despite Mgr. Benson's subtle contempt for "Greek Christianity",[71] Mother Catherine Abrikosova, a Byzantine Catholic Dominican nun, former Marxist, and future martyr in Joseph Stalin's concentration camps, translated Lord of the World from English to Russian shortly before the Bolshevik Revolution.[72]

Legacy

Catholic intellectuals

Although it is not as well known as the dystopian writings of Evgeny Zamyatin, George Orwell, and Aldous Huxley, Lord of the World continues to have many admirers—especially among Conservative and Traditionalist Catholics.

Reviewer Mary Whitebrough noted: [73] "It is commonly believed than Benson wrote Lord of the World at least partly in response to the writings of H.G.Wells with their vision of a technologically-advanced secularized future in store for humanity. But it is also possible that Wells, a veteran of numerous debates with Catholics, may have returned the favor. Wells' own The Shape of Things to Come takes up the basic plot element of Lord of the World and turns it upside down. In Things to Come, too, a secularized World Government embarks on a head-on confrontation with the Catholic Church and eventually destroys it - but for Wells, the World Secularists are the Good Guys and destroying the Church is a necessary, positive act. (...) To be sure, Wells' World Government is far less brutal than the one predicted by Benson. In Wells' version The Pope and Cardinals are simply dosed with sleeping gas, rather than being firebombed, and Catholics are mainly educated out of their reactionary ways rather than persecuted into martyrdom.(...) It is amusing to note that the Catholic Benson and the Secularist Wells were at one in dismissing the Protestants' power of resistance and seeing only the Catholic Church as a worthy opponent for Secularism. (...) The Three super states into which the world of "Lord of the World" is divided - American Republic, European Confederation and Eastern Empire - prefigure George Orwell's Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia in the world of Nineteen Eighty Four. Orwell, omnivorous relentless reader that he was, had likely read "Lord of the World".

In a 2005 essay, Joseph Pearce wrote that, while Orwell and Huxley's novels are "great literature", they "are clearly inferior works of prophecy." Pearce explains that while "the political dictatorships" that inspired Huxley and Orwell "have had their day", "Benson's novel-nightmare... is coming true before our very eyes."[74]

Pearce elaborates,

The world depicted in Lord of the World is one where creeping secularism and godless humanism have triumphed over traditional morality. It is a world where philosophical relativism has triumphed over objectivity; a world where, in the name of tolerance, religious doctrine is not tolerated. It is a world where euthanasia is practiced widely and religion hardly practiced at all. The lord of this nightmare world is a benign-looking politician intent on power in the name of "peace", and intent on the destruction of religion in the name of "truth". In such a world, only a small and shrinking Church stands resolutely against the demonic "Lord of the World".[75]

EWTN talk show host and American Chesterton Society President Dale Ahlquist has also praised Monsignor Benson's novel and said that it deserves a wider audience.[76]

Michael D. O'Brien's has cited it as an influence on his Apocalyptic series Children of the Last Days.

Papal statements

On February 8, 1992, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger criticized U. S. President George H. W. Bush's recent speech calling for "a New World Order" in a speech of his own at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore. In his discourse, the future Pope explained that Monsignor Benson's novel described "a similar unified civilization and its power to destroy the spirit. The anti-Christ is represented as the great carrier of peace in a similar new world order."[77]

Cardinal Ratzinger proceeded to quote from Pope Benedict XV's 1920 encyclical Bonum sane: "The coming of a world state is longed for, by all the worst and most distorted elements. This state, based on the principles of absolute equality of men and a community of possessions, would banish all national loyalties. In it no acknowledgement would be made of the authority of a father over his children, or of God over human society. If these ideas are put into practice, there will inevitably follow a reign of unheard-of terror."[77]

In a sermon in November, 2013, Pope Francis praised Lord of the World as depicting "the spirit of the world which leads to apostasy almost as if it were a prophecy."[2]

In early 2015, Pope Francis further revealed Benson's influence upon his thinking, speaking to a plane load of reporters. At first apologizing for making "a commercial", Pope Francis further praised Lord of the World, despite its being "a bit heavy at the beginning". Pope Francis elaborated, "It is a book that, at that time, the writer had seen this drama of ideological colonization and wrote that book... I advise you to read it. Reading it, you'll understand well what I mean by ideological colonization."[78]

External Link

References

- Robert Hugh Benson, Lord of the World, London. Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd. 1907.

- Pope Francis Denounces "Adolescent Progressivism" Calls "Lord of the World" Prophetic, Catholic News Service, November 19, 2013.

- Joseph Pearce (2006), Literary Converts: Spiritual Inspiration in an Age of Unbelief, Ignatius Press. Pages 17–27.

- Pearce (2006), page 27.

- Pearce (2006), pages 27–28.

- Martindale (1916) Volume II, page 65.

- Martindale (1916), page 78.

- Benson, Lord of the World, Saint Augustine's Press, 2011. Page 3.

- Benson (2011), page 7.

- In the European and Asian power blocs and their prevention from going to war by the intervention of the Anti-Christ, Lord of the World is very similar to "A Short Tale of the Anti-Christ", written in 1900 by Vladimir Solovyov. There is no evidence, however, that Monsignor Benson was in any way influenced by or even aware of Solovyov.

- Benson (2011), page 19.

- Benson (2011), pages 19–22

- Benson (2011), pages 22–25.

- Benson (2011), pages 28–33.

- Benson (2011), pages 37–41.

- Benson (2011), pages 44–52.

- Benson (2011), pages 52–56.

- Benson (2011), pages 58–68.

- Benson (2011), pages 69–74.

- Benson (2011), pages 74–78.

- Benson (2011), pages 79–81.

- Benson (2011), pages 81–82.

- Benson (2011), pages 82–84.

- Benson (2011), pages 87–93.

- Benson (2011), pages 94–107.

- Benson (2011), pages 106–110.

- Benson (2011), page 110.

- Benson (2011), pages 111–112.

- Benson (2011), pages 113–114.

- Benson (2011), page 115.

- Benson (2011), pages 115–116.

- Benson (2011), page 116.

- Benson (2011), page 117.

- Benson (2011), page 120.

- Benson (2011), pages 122–128.

- Benson (2011), page 137.

- Benson (2011), pages 133–135, 136–140.

- Benson (2011), page 136.

- Benson (2011), pages 129–133.

- Benson (2011), pages 140–141.

- Benson (2011), pages 143–144.

- Benson (2011), pages 144–145.

- Benson (2011), pages 145–146.

- Benson (2011), pages 147–149.

- Benson (2011), pages 149–150.

- Benson (2011), pages 152–166.

- Benson (2011), pages 167–176.

- Benson (2011), pages 177–178.

- Benson (2011), page 189.

- When Lord of the World was published in 1907, the Antipopes Alexander V and John XXIII were seen as validly elected Roman Pontiffs. Therefore, Monsignor Benson's Pope John is "XXIV" rather than "XXIII". As Pope Silvester III was then seen as an Antipope, Monsignor Benson's Pope Silvester is "III" rather than "IV".

- Benson (2011), page 236.

- Benson (2011), page 259.

- Benson (2011), page 260.

- Martindale (1916) Volume 2. pp. 68–69.

- Martindale (1916), pages 69, 78.

- Martindale (1916), page 74.

- Benson (2011), pages 240–244.

- C. C. Martindale, S.J. (1916), The Life Of Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson, Volume 2, Longmans, Green and Co, London. pp. 65–66.

- Martindale (1916), Volume 2, page 66.

- Martindale (1916), page 68.

- Martindale (1916), page 77.

- Martindale (1916), Volume 2, page 73.

- Martindale (1916), Volume 2, page 75.

- Martindale (1916), Volume 2, page 57.

- Martindale (1916), pages 74–75.

- Martindale (1916), page 79.

- Martindale (1916), pages 75–76.

- Martindale (1916), pages 78–79.

- Martindale (1916), page 76.

- Joseph Pearce (2006), Literary Converts: Spiritual Inspiration in an Age of Unbelief, Ignatius Press, San Francisco. Page 40-41.

- Benson (2011), page 195.

- Kathleen West, The Regular Tertiaries of St. Dominic in Red Moscow, Blackfriars, June 1925. pp. 322–327.

- Mary C. Whitebrough, "The Debates and Interactions of Catholics and Secularists in Early Twentieth Century England" in Dr. Bernard Weiman (ed.) "A Retrospective Look on the Intellectual Developments of the Twentieth Century"

- Pearce (2005), Literary Giants, Literary Catholics, page 141.

- Pearce (2005), page 141.

- Dale Ahlquist (May 2011). "A surprising book about the end of the world, but we know that the world ends" (PDF). The Catholic Servant. p. 12.

- "Who is Joseph Ratzinger? A biography of the new Pope". Michael (334). April 2005. p. 16.

- Alan Holdren (January 19, 2015). "Full text of Pope's in-flight interview from Manila to Rome". Catholic News Agency.

Further reading

- Ahlquist, Dale (2012). "The End of the World," The American Chesterton Society, March 12.

- Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers. p. 48.

- Cuddy, Denis L. (2005). "Lord of the World," News with Views, April 20.

- Martindale, C.C. (1916). The Life of Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson, Vol. 2. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- McCloskey, Fr. John. "Introduction to Benson's 'Lord of the World'," Catholic City, [n.d.].

- Rutler, Fr. George W. (2008). "The One We Were Waiting For," National Review, November 3.

- Schall, Rev. James V. (2012). "The Lord of the World," Crisis Magazine, July 10.

- Wood. Joseph (2009). "Lord of the World," The Catholic Thing, March 31.

External links

- "Lord of the World", Ex Fontibus Co., 2015. ISBN 978-1507790502

- "Lord of the World", St. Augustine's Press, 2001. ISBN 1-890318-38-8

- "Lord of the World" complete text online at Authorama.com – public domain books

- "Lord of the World" complete text from Project Gutenberg.

- "Lord of the World", Dood, Mead & Company, 1908 1917, from Internet Archive.

- "Lord of the World", Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1918, from Hathi Trust.

- "Lord of the World", YouTube film – free of copyright.

.jpg)