Simon Vouet

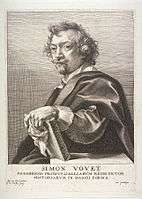

Simon Vouet (French: [vwɛ]; 9 January 1590 – 30 June 1649) was a French painter who studied and rose to prominence in Italy before being summoned by Louis XIII to serve as Premier peintre du Roi in France. He and his studio of artists created religious and mythological paintings, portraits, frescoes, tapestries, and massive decorative schemes for the king and for wealthy patrons, including Richelieu. During this time, "Vouet was indisputably the leading artist in Paris,"[1] and was immensely influential in introducing the Italian Baroque style of painting to France. He was also "without doubt one of the outstanding seventeenth-century draughtsmen, equal to Annibale Carracci and Lanfranco."[2]

Simon Vouet | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait (c. 1626–1627) Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon | |

| Born | 9 January 1590 Paris, France |

| Died | 30 June 1649 (aged 59) Paris, France |

| Education | Father's studio, years in Italy (1613–1627) |

| Known for | Painting, Drawing |

| Movement | Baroque |

| Patron(s) | Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu |

Career

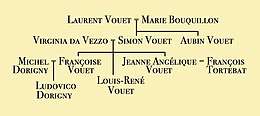

Simon Vouet was born on January 9, 1590 in Paris.[3] His father Laurent was a painter in Paris and taught him the rudiments of art. Simon's brother Aubin Vouet was also a painter, as also was Simon's wife Virginia da Vezzo, their son Louis-René Vouet, their two sons-in-law, Michel Dorigny and François Tortebat, and their grandson Ludovico Dorigny.

Simon began his career as a portrait painter. At age 14 he travelled to England to paint a commissioned portrait and in 1611 was part of the entourage of the Baron de Sancy, French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, for the same purpose. From Constantinople he went to Venice in 1612 and was in Rome by 1614.[4][5]

He remained in Italy until 1627, mostly in Rome where the Baroque style was becoming dominant. He received a pension from the King of France and his patrons included the Barberini family, Cassiano dal Pozzo, Paolo Giordano Orsini and Vincenzo Giustiniani.[4] He also visited other parts of Italy: Venice; Bologna (where the Carracci family had their academy); Genoa (where, from 1620 to 1622, he worked for the Doria princes); and Naples.

He was a natural academic, who absorbed what he saw and studied, and distilled it in his painting: Caravaggio's dramatic lighting; Italian Mannerism; Paolo Veronese's color and di sotto in su or foreshortened perspective; and the art of Carracci, Guercino, Lanfranco and Guido Reni.

Vouet's immense success in Rome led to his election as president of the Accademia di San Luca in 1624.[6] His most prominent official commission of the Italian period was an altarpiece for St Peter's in Rome (1625–1626), destroyed at some time after 1725 (though fragments remain.)[7]

In response to a royal summons, Vouet returned to France in 1627, where he was made Premier peintre du Roi. Louis XIII commissioned portraits, tapestry cartoons and paintings from him for the Palais du Louvre, the Palais du Luxembourg and the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. In 1632, he worked for Cardinal Richelieu at the Palais-Royal and the Château de Malmaison. In 1631 he decorated the château of the président de Fourcy, at Chessy, the hôtel Bullion, the château of Marshal d'Effiat at Chilly, the hôtel of the Duc d’Aumont, the Séguier chapel, and the gallery of the Château de Wideville.

Today, a number of Vouet's paintings are lost, and "only two major decorative schemes survive, those for the chateaux of Colombes and Chessy,"[8] but the details and imagery of many lost works are known from engravings by Michel Dorigny, François Tortebat, and Claude Mellan.[4]

Personal life

In 1626 he married Virginia da Vezzo, "a painter in her own right...known for her beauty,"[9]:10 who modeled as the Madonna and female saints for Vouet's religious commissions. The couple would have five children. Virginia Vouet died in France in 1638. Two years later Vouet married a French widow, Radegonde Béranger, with whom he had three more children.[9]:13

Legacy

As one art historian writes, "When Vouet returned to Paris in 1627, French art was painfully provincial and, by Italian standards, more than a quarter of a century behind the times. Vouet introduced the latest fashions, educated a group of talented young artists—and the public as well—and brought Paris up to date."[1]

Vouet's style became uniquely his own, but was distinctly Italian, importing the Italian Baroque into France. A French contemporary, lacking the term "Baroque," said, "In his time the art of painting began to be practiced here in a nobler and more beautiful way than ever before." In his anticipation of the "two-dimensional, curvilinear freedom of rococo compositions a hundred years later...Vouet should perhaps be counted among the more important sources of eighteenth-century painting."[9]:60 In his works for the French royal court, "Vouet's importance as a formulator of official decorations is in some ways comparable to that of Rubens."[9]:85

Vouet's sizeable atelier or workshop produced a whole school of French painters for the following generation. His most influential pupil was Charles le Brun, who organized all the interior decorative painting at Versailles and dictated the official style at the court of Louis XIV of France, but who jealously excluded Vouet from the Académie Royale in 1648.

Vouet's other students included Valentin de Boulogne (the main figure of the French "Caravaggisti"), François Perrier, Nicolas Chaperon, Michel Corneille the Elder, Charles Poërson, Pierre Daret, Charles Alphonse du Fresnoy, Pierre Mignard, Eustache Le Sueur, Claude Mellan, the Flemish artist Abraham Willaerts, Michel Dorigny, and François Tortebat. These last two became his sons-in-law. André Le Nôtre, the garden designer of Versailles, was a student of Vouet. Also in Vouet's circle was a friend from his Italian years, Claude Vignon.

During his lifetime, writes Arnaud Brejon de Lavergnée, "Vouet's stature increased continually, his paintings becoming ever more beautiful, particularly in the last decade." But, "although his career was as brilliant as can be imagined," Vouet "played no role in the foundation of the Académie Royale" that was to be so dominant after his death, "and was neglected by the biographers and more influential amateurs. Between 1660 and 1690 only Poussin and Rubens were taken seriously...and later generations drew their own conclusions from this." Further eroding his legacy, "Vouet was undoubtedly at his greatest in these ensembles [his magnificent decorative schemes for chateaux and churches], most of which were destroyed during the Revolution" of the next century.[8]

Though never entirely forgotten by connoisseurs and collectors (such as William Suida), Vouet fell into a relative obscurity that was not remedied until William R. Crelly's monograph of 1962,[9] and then by the major retrospective of Vouet's work at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1990–1991 with its colloquium[10] and catalogue,[11] which Brejon de Lavergnée says fulfilled "its aim of rehabilitating the artist."[8] "The Simon Vouet retrospective…is still vividly remembered. Since then, studies of the painter, his circle and his students have abounded, defining the image of the artist and his workshop ever more clearly."[12]

The exhibition's organizer, Jacques Thuillier, "is surely justified in claiming the altarpiece of the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple as among the greatest masterpieces of seventeenth-century monumental painting," writes Brejon de Lavergnée, who further asserts that in the artist's works of the 1640s, such as Saint Francis of Paola Resuscitating a Child, "one can see Vouet concluding his career with pictures of an immense gravity informed by an intense spiritual energy. Images of the greatesf force, these paintings constitute the apogee of French seventeenth-century painting."[8]

Two Modelli for Altarpiece in St. Peter's (1625), LACMA

Two Modelli for Altarpiece in St. Peter's (1625), LACMA

Exhibitions

- 1967: Vouet to Rigaud: French Masters of the Seventeenth Century, Finch College Museum of Art, New York, 20 April 1967 – 18 June 1967.

- 1971: Simon Vouet 1590-1649: First Painter to the King, University of Maryland Art Gallery, College Park, MD, 18 February 1971 – 28 March 1971.

- 1990–1991: Vouet, Galeries Nationales of the Grand Palais, Paris, 6 November – 11 February 1991; a major retrospective of Simon Vouet's work.

- 1991: Simon Vouet : 100 neuentdeckte Zeichnungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich, 9 May – 30 June 1991; exhibition of 100 newly discovered drawings from the holdings of the Bavarian State Library.

- 2002–2003 : Simon Vouet ou l'éloquence sensible, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, 5 December 2002 – 20 February 2003; exhibition of drawings from the Bavarian State Library in Munich.

- 2005–2006: Loth et ses filles de Simon Vouet: Éclairages sur un chef-d'œuvre, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, 22 October 2005 – 22 January 2006.

- 2008–2009: Simon Vouet, les années italiennes (1613–1627), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, 21 November 2008 – 23 February 2009, and Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie de Besançon, 27 March – 29 June 2009.

.jpg)

Works

Paintings

Crelly's catalogue raisonné of 1962[9]:147 lists more than 150 preserved paintings by Vouet. Since that publication, "a number of paintings, some of them of considerable importance, have turned up in various parts of the world and the list of his work continues to grow."[15] A new catalogue raisonné, by Arnauld and Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée, is forthcoming.[16] This is a partial list by present location, and then, as possible, by date.

Louvre, Paris

- Prince Marcantonio Doria d'Angri (1621)

- Saint William of Aquitaine (1622–1627)

- The Holy Family with St Elisabeth and the Infant St John the Baptist (1625–1650)

- Allegory of Wealth (c. 1635–1640)

- Allegory of Charity (1630–1635)

- Gaucher de Châtillon (1632–1635)

- Allegory of Virtue (c. 1634)

- Heavenly Charity (c. 1640)

- Presentation of Jesus in the Temple (1641)

- Hesselin Madonna or Madonna of the Oak Cutting (c.1640–1645)

- Portrait of Louis XIII between two female figures symbolising France and Navarre (1643)

- Portrait of a Young Man

- Polymnia, Muse of Eloquence

Elsewhere in France

- Presumed portrait of Aubin Vouet, the artist's brother (c. 1620), Musée Réattu, Arles

- Cupid and Psyche (1626–1629), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

- Self-portrait (1626–1627), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

- Suite of the loves of Rinaldo and Armida (1631), based on Tasso's epic poem Jerusalem Delivered, collection of Guyot de Villeneuve, Paris

- Repentant Magdalen (1633), Musée de Picardie, Amiens

- Ceres Trampling the Attributes of War (1635), Musée des Beaux-arts Thomas Henry, Cherbourg-Octeville

- Deposition of Christ (c.1635), Musée d'art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre

- Lot and his Daughters (1633), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, subject of a special exhibit in 2005-2006[17]

- Crucifixion (1636–1637), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

- The Four Cardinal Virtues—Allegory of Temperance, Allegory of Force, Allegory of Prudence, Allegory of Justice (1638), Salon de Mars, Versailles

- Death of Dido (c. 1641), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dole

- Time Vanquished by Love, Venus and Hope (1640-1645), Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Bourges

- Last Supper, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

Italy

- Mary Magdalene (1614–1615), Quirinal Palace, Rome

- Angel with Dice and Tunic and Angel with Spear of the Passion (1615–1625), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

- Last Supper (1616–1620), Palazzo Comunale, Loreto

- Crucifixion (1621–6122), Chiesa del Gesù, Genoa

- David with the Head of Goliath (1620–1622), Palazzo Bianco, Genoa

- Nativity of the Virgin (c. 1629), San Francesco a Ripa, Rome

- Annunciation (c. 1621–1622), Uffizi, Florence

- Circumcision of Jesus (1622), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

- Portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi with Painting Implements (c. 1623–1625), private collection

- Temptation of Saint Francis and Saint Francis Renouncing His Goods (1624–1625), San Lorenzo in Lucina, Rome

- Saint Agatha's Vision of Saint Peter in Prison (c. 1625), Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo

Elsewhere in Europe

- The Annunciation (n.d.), Pushkin Museum, Moscow

- Lovers (1614–1618), Pushkin Museum, Moscow

- Judith (1620–1622), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Ill-Matched Couple (Vanitas) (c. 1621), National Museum, Warsaw

- Sophonisba Receiving the Poisoned Chalice (c. 1623), Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

- Time Vanquished by Love, Beauty and Hope (1627), Prado, Madrid

- Diana (1637), Cumberland Gallery, Hampton Court Palace, England

- Sleeping Venus (1630–1640), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- Parnassus, or Apollo and the Muses (c. 1640) Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- The Awakening of Europa (1640), Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

- Artemisia Building the Mausoleum (early 1640s), Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

- Judith, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- Saint Jerome (c.1620), National Library of Wales, Wales

United States

- Saint Agnes (c. 1615), Blanton Museum of Art, Austin

- The Halberdier (c. 1615–1620), Dayton Art Institute

- Woman Playing a Guitar (c. 1618), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Portrait of a Gentleman (c. 1620), Blanton Museum of Art, Austin

- Saint Luke and Saint John (1622–1625), Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Saint Jerome and the Angel (c. 1622–1625), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Two Modelli for Altarpiece in St. Peter's (1625), LACMA, Los Angeles

- Saint Sebastian (c. 1625), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (1626), Legion of Honor, San Francisco

- Saint Cecilia (c. 1626), Blanton Museum of Art, Austin

- Salome (1626–1627), Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento

- Angels with Attributes of the Passion: Angel Holding the Vessel and Towel for Washing the Hands of Pontius Pilate and Angel with the Superscription from the Cross (1627), Minneapolis Institute of Arts

- Virginia da Vezzo, the Artist's Wife, as the Magdalen (c. 1627), LACMA, Los Angeles

- Saint Mary Magdalen (c. 1630), Cleveland Museum of Art

- Diana and Endymion and Neptune and Amphitrite (1630s),[15] Hearst Castle, San Simeon

- Madonna and Child (1633), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Aeneas and His Father Fleeing Troy (c. 1635), San Diego Museum of Art

- The Toilet of Venus (1640), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

- Venus and Adonis (1642), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Canada

- The Fortune-teller (c. 1620), National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- Apparition of the Virgin and the Infant Jesus to Saint Anthony (1630–1631), by Vouet in collaboration with François Perrier, L’église Saint-Roch de Quebec, Quebec City

- Saint Francis of Paola Resuscitating a Child (1648), L'église-Saint-Henri de Lévis, Quebec

Japan

- St. Catherine (n.d.), National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

%2C_tapestry_from_the_workshop_of_Raphael_de_la_Planche_based_on_design_by_Simon_Vouet.jpg)

Tapestries

Compositions by Vouet preserved in tapestries[9]:266 include:

- Twelve tapestries based on scenes from Tasso's epic poem Jerusalem Delivered, including Rinaldo in the Arms of Armida at the Louvre.

- Six tapestries from the series The Story of Theagenes and Chariclea (1634–1635), based on scenes from the ancient Greek novel Aethiopica, at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco.

- Eight tapestries based on scenes from the Old Testament, including Moses Saved from the Waters (The Finding of Moses) (c. 1630) at the Louvre.

- Eight tapestries based on scenes from the Oddysey.

- Twenty-three tapestries based on Loves of the Gods, including Neptune and Ceres and Aurora and Cephalus at the Hôtel de Sully.

Gallery of paintings (chronological)

Parnassus, or Apollo and the Muses (c. 1640), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Parnassus, or Apollo and the Muses (c. 1640), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

St. Catherine (n.d.), National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

St. Catherine (n.d.), National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo Mary Magdalen (1614–1615), Quirinal Palace, Rome

Mary Magdalen (1614–1615), Quirinal Palace, Rome Lovers (1614–1618), Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Lovers (1614–1618), Pushkin Museum, Moscow Saint Agnes (c. 1615), Blanton Museum of Art

Saint Agnes (c. 1615), Blanton Museum of Art Woman Playing a Guitar (c. 1618), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Woman Playing a Guitar (c. 1618), Metropolitan Museum of Art- The Halberdier (c. 1615–1620), Dayton Art Institute

Angel with Dice and Tunic (1615–1625), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

Angel with Dice and Tunic (1615–1625), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples Angel with Spear of the Passion (1615–1625), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

Angel with Spear of the Passion (1615–1625), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples Portrait of a Gentleman (c. 1620), Blanton Museum of Art

Portrait of a Gentleman (c. 1620), Blanton Museum of Art_(kwf00534).jpg) Saint Jerome (c..1620), National Library of Wales, Wales

Saint Jerome (c..1620), National Library of Wales, Wales The Fortune-teller (c. 1620), National Gallery of Canada

The Fortune-teller (c. 1620), National Gallery of Canada- The Ill-Matched Couple (Vanitas) (c. 1621), National Museum, Warsaw

Judith (1620–1622), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Judith (1620–1622), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Circumcision of Jesus (1622), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

Circumcision of Jesus (1622), Museo di Capodimonte, Naples- Judith (c.1620-1625), Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Saint Luke (1622–1625), Philadelphia Museum of Art

Saint Luke (1622–1625), Philadelphia Museum of Art Saint John (1622–1625), Philadelphia Museum of Art

Saint John (1622–1625), Philadelphia Museum of Art Saint Jerome and the Angel (c. 1622–1625), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Saint Jerome and the Angel (c. 1622–1625), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Saint William of Aquitaine (1622–1627), Louvre

Saint William of Aquitaine (1622–1627), Louvre Sophonisba Receiving the Poisoned Chalice (c. 1623), Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

Sophonisba Receiving the Poisoned Chalice (c. 1623), Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi with Painting Implements (c. 1623–1625), private collection

Portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi with Painting Implements (c. 1623–1625), private collection Saint Agatha's Vision of Saint Peter in Prison (c. 1625), Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo

Saint Agatha's Vision of Saint Peter in Prison (c. 1625), Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo Saint Sebastian (c. 1625), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Saint Sebastian (c. 1625), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Saint Cecilia (c. 1626), Blanton Museum of Art

Saint Cecilia (c. 1626), Blanton Museum of Art- The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (1626), Legion of Honor, San Francisco

Salome (1626–1627), Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento

Salome (1626–1627), Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento Cupid and Psyche (1626-1629), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

Cupid and Psyche (1626-1629), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon Angel Holding the Vessel and Towel for Washing the Hands of Pontius Pilate (1627), Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Angel Holding the Vessel and Towel for Washing the Hands of Pontius Pilate (1627), Minneapolis Institute of Arts Angel with the Superscription from the Cross (1627), Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Angel with the Superscription from the Cross (1627), Minneapolis Institute of Arts Time Vanquished by Love, Beauty and Hope (1627), Prado

Time Vanquished by Love, Beauty and Hope (1627), Prado Nativity of the Virgin (c. 1629), San Francesco a Ripa, Rome

Nativity of the Virgin (c. 1629), San Francesco a Ripa, Rome Saint Mary Magdalene (c. 1630), Cleveland Museum of Art

Saint Mary Magdalene (c. 1630), Cleveland Museum of Art Neptune and Amphitrite (1630s) Hearst Castle

Neptune and Amphitrite (1630s) Hearst Castle Madonna and Child (1633), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Madonna and Child (1633), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Lot and His Daughters (1633), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg

Lot and His Daughters (1633), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg Ceres Trampling the Attributes of War (1635), Musée des Beaux-arts Thomas Henry, Cherbourg-Octeville

Ceres Trampling the Attributes of War (1635), Musée des Beaux-arts Thomas Henry, Cherbourg-Octeville- Aeneas and his Father Fleeing Troy (c. 1635), San Diego Museum of Art

Deposition of Christ (c.1635), Musée d'art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre

Deposition of Christ (c.1635), Musée d'art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre Allegory of Wealth (c. 1635–1640), Louvre

Allegory of Wealth (c. 1635–1640), Louvre Diana (1637), Cumberland Gallery, Hampton Court Palace

Diana (1637), Cumberland Gallery, Hampton Court Palace Sleeping Venus (1630–1640), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Sleeping Venus (1630–1640), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest Heavenly Charity (c. 1640), Louvre

Heavenly Charity (c. 1640), Louvre The Toilet of Venus (c. 1640), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

The Toilet of Venus (c. 1640), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh The Death of Dido (c. 1641), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dole

The Death of Dido (c. 1641), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dole_-_Nationalmuseum_-_22229.tif.jpg) Artemisia Building the Mausoleum (early 1640s), Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Artemisia Building the Mausoleum (early 1640s), Nationalmuseum, Stockholm Venus and Adonis (1642), J. Paul Getty Museum

Venus and Adonis (1642), J. Paul Getty Museum_n01.jpg) Portrait of Louis XIII (1643), Louvre

Portrait of Louis XIII (1643), Louvre Hesselin Madonna or Madonna of the Oak Cutting (c. 1640–1645), Louvre

Hesselin Madonna or Madonna of the Oak Cutting (c. 1640–1645), Louvre Time Vanquished by Love, Venus and Hope (1640-1645), Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Bourges

Time Vanquished by Love, Venus and Hope (1640-1645), Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Bourges- Cabinet attributed to Pierre Gole[18] (c.1620-1684), Legion of Honor, San Francisco

Gallery: Images of Vouet and his family

Circle of Simon Vouet, presumed portrait of Vouet (c. 1615–1620)

Circle of Simon Vouet, presumed portrait of Vouet (c. 1615–1620) Simon Vouet, Self-portrait, Uffizi

Simon Vouet, Self-portrait, Uffizi Simon Vouet, presumed self-portrait (c. 1620-1625), Musée de Picardie

Simon Vouet, presumed self-portrait (c. 1620-1625), Musée de Picardie Ottavio Leoni, Portrait of Simon Vouet (1625)

Ottavio Leoni, Portrait of Simon Vouet (1625) Simon Vouet, Self-portrait (c.1626–1627) Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

Simon Vouet, Self-portrait (c.1626–1627) Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon Nicolas Mignard, Portrait of Simon Vouet

Nicolas Mignard, Portrait of Simon Vouet François Perrier, Portrait of Simon Vouet (1632)

François Perrier, Portrait of Simon Vouet (1632) Robert Van Voerst (after Anthony van Dyck), Portrait of Simon Vouet

Robert Van Voerst (after Anthony van Dyck), Portrait of Simon Vouet Portrait of Simon Vouet by his son-in-law, François Tortebat, Versailles

Portrait of Simon Vouet by his son-in-law, François Tortebat, Versailles Simon Vouet, Presumed portrait of Aubin Vouet, the artist's brother (c. 1620), Musée Réattu, Arles

Simon Vouet, Presumed portrait of Aubin Vouet, the artist's brother (c. 1620), Musée Réattu, Arles Claude Mellan, Portrait of Virginia da Vezzo (1626), wife of Simon Vouet

Claude Mellan, Portrait of Virginia da Vezzo (1626), wife of Simon Vouet Simon Vouet, Virginia da Vezzo, the Artist's Wife, as the Magdalen (c. 1627), LACMA

Simon Vouet, Virginia da Vezzo, the Artist's Wife, as the Magdalen (c. 1627), LACMA Simon Vouet, Portrait of Angélique Vouet (his daughter), pastel, Louvre

Simon Vouet, Portrait of Angélique Vouet (his daughter), pastel, Louvre

References

- Posner, Donald. "The Paintings of Simon Vouet " (book review), The Art Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Sept., 1963), pp. 286-291.

- Rosenberg, Pierre."Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins, Inventaire général des dessins, École française, Dessins de Simon Vouet 1590-1649 by Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée" (book review). Master Drawings, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Winter, 1987), p. 414.

- Simon Vouet at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Barbara. 'Simon Vouet', Oxford Art Online.

- "Artist Info". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Bissell, R. Ward (2011). "Simon Vouet, Raphael, and the Accademia di San Luca in Rome". Artibus et Historiae. 32 (63): 55–72. JSTOR 41479737.

- Schleier, Erich. "A Bozzetto by Vouet, Not by Lanfranco." The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 109, No. 770 (May, 1967), pp. 272, 274–276.

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. "Paris: Vouet at the Grand Palais" (review of the exhibition). The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 133, No. 1055 (Feb. 1991), pp. 136–140.

- Crelly, William R. The Paintings of Simon Vouet. Yale University Press, 1962.

- Loire Stéphane, eitor. Simon Vouet: actes du colloque international Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 5-6-7 février 1991, Paris: Publication Information, c1992.

- Thuillier, Jacques. Vouet: Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, 6 novembre 1990-11 février 1991 (catalogue of the exhibition). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, c. 1990.

- Rykner, Didier. "Simon Vouet: The Italian Years 1613/1617 (review of the exhibit)". thearttribune.com. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- Durox, Solenne. "Confisqués pendant la Révolution, ces tableaux ont beaucoup voyagé." Le Parisien, 4 November 2017.

- "Patrimoine religieux : aide financière pour les églises Saint-Roch et Saint-Sauveur". monsaintroch.com. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- Fredericksen, Burton B. "Two Newly Discovered Ceiling Paintings by Simon Vouet." The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Vol. 5 (1977), pp. 95–100.

- "Simon Vouet, Study of a Young Woman as the Virgin". sothebys.com. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "Loth et ses filles de Simon Vouet: Éclairages sur un chef-d'œuvre". www.musees.strasbourg.eu.

- "The carvings on the exterior doors may derive from Simon Vouet," according to Renée Dreyfus, Legion of Honor: Selected Works, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco: 2007, p. 51.

Bibliography

- Bissell, R. Ward (2011). "Simon Vouet, Raphael, and the Accademia di San Luca in Rome." Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 32, No. 63 (2011), pp. 55–72.

- Blunt, Anthony. "Some Portraits by Simon Vouet." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 88, No. 524 (Nov., 1946), pp. 268+270-271+273.

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. "Four New Paintings by Simon Vouet." The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 124, No. 956 (Nov., 1982), pp. 685–689.

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. "Paris: Vouet at the Grand Palais" (review of the exhibition). The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 133, No. 1055 (Feb., 1991), pp. 136–140.

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. "Simon Vouet. Nantes and Besançon" (review of the exhibition). The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 151, No. 1272 (Mar., 2009), pp. 187–189.

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Barbara. Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins, Inventaire général des dessins, École française, Dessins de Simon Vouet 1590-1649. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1987. (Comprehensive catalogue of the drawings of Vouet in the Louvre and elsewhere.)

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Barbara. "New Attributions around Simon Vouet." Master Drawings, Vol. 23/24, No. 3 (1985/1986), pp. 347–351+425-432.

- Brejon de Lavergnée, Barbara. "Some New Pastels by Simon Vouet: Portraits of the Court of Louis XIII." The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 124, No. 956 (Nov., 1982), pp. 688–691+693.

- Crelly, William R. The Painting of Simon Vouet. Yale University Press, 1962.

- Fredericksen, Burton B. "Two Newly Discovered Ceiling Paintings by Simon Vouet." The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Vol. 5 (1977), pp. 95–100.

- Gomez, Susana. "The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics. The Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet". Nuncius: Journal of the Material and Visual History of Science, vol. 31, issue 2, pp. 288–331.

- Loire Stéphane, eitor. Simon Vouet: actes du colloque international Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 5-6-7 février 1991. Paris: Publication Information, c1992.

- Loth et ses filles de Simon Vouet: Éclairages sur un chef-d'œuvre (catalogue of the exhibition). Strasbourg: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, 2005.

- Lurie, Ann Tzeutschler. "The Repentant Magdalene by Simon Vouet." The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Vol. 80, No. 4 (Apr., 1993), pp. 158–163.

- Manning, Robert. "Some Important Paintings by Simon Vouet in America" in Studies in the History of Art, Dedicated to William E. Suida on His Eightieth Birthday. Kress Foundation/Phaidon Press, 1959.

- Markova, Vittoria. "A New Painting by Vouet in Russia." The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 132, No. 1050 (Sept., 1990), pp. 632–633.

- Posner, Donald. "The Painting of Simon Vouet " (book review). The Art Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Sept., 1963), pp. 286-291.

- Rice, Louise. "Simon Vouet's Hesperus and the Mythopoetics of Praise." Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 74, Symposium Papers LI: Dialogues in Art History, from Mesopotamian to Modern: Readings for a New Century (2009), pp. 236-251.

- Schleier, Erich. "A Bozzetto by Vouet, Not by Lanfranco." The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 109, No. 770 (May, 1967), pp. 272+274-276.

- Schleier, Erich. "Two New Modelli for Vouet's St. Peter's Altarpiece." The Burlington Magazine Vol. 114, No. 827 (Feb., 1972), pp. 90-94.

- Schleier, Erich. "Vouet's Destroyed St Peter Altar-Piece: Further Evidence." The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 110, No. 787 (Oct., 1968), pp. 572-575.

- Simon Vouet: 100 neuentdeckte Zeichnungen: aus den Beständen der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek (catalogue of the exhiition). München: Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München, 1991.

- Simon Vouet ou l'éloquence sensible: Dessins de la Staatsbibliothek de Munich (catalogue of the exhibition). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux; Nantes: Musée des beaux-arts de Nantes, c. 2002.

- Simon Vouet: les années italiennes, 1613-1627 (catalogue of the exhibition). Paris: Hazan; Nantes: Musée des beaux-arts; Besançon: Musée des beaux-arts et d'archéologie, 2008.

- Thuillier, Jacques. Vouet: Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, 6 novembre 1990-11 février 1991 (catalogue of the exhibition). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, c. 1990.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paintings by Simon Vouet. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Simon Vouet. |

- Three portraits by the artist who taught Louis XIII to draw, auctioned at Christie's 27 May 2020

- 10 paintings by or after Simon Vouet at the Art UK site

- Simon Vouet at Google Arts & Culture

- Works at WGA

- Simon Vouet paintings at the Hearst Castle in California

- Simon Vouet's Saint Agnes, Saint Cecilia, and Portrait of a Gentleman at the Blanton Museum of Art

- Simon Vouet at the J. Paul Getty Museum

- Online Vouet Gallery at MuseumSyndicate

- Article about Vouet and his wife and fellow painter Virginia da Vezzo (in Italian)

- Sylvain Kerspern on portraits depicting Simon Vouet (in French)

- L'homme à la figue (Man with figs), a look at the coded sexual meaning of Vouet's painting at Caen (in French)