Labweh

Labweh (Arabic: اللبوة), Laboué, Labwe or Al-Labweh is a village at an elevation of 950 metres (3,120 ft) on a foothill of the Anti-Lebanon mountains in Baalbek District, Baalbek-Hermel Governorate, Lebanon.[1][2] It is famous because of the archaeological remains, like a Roman temple converted in a Byzantine fortress.

اللبوة | |

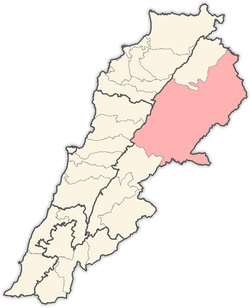

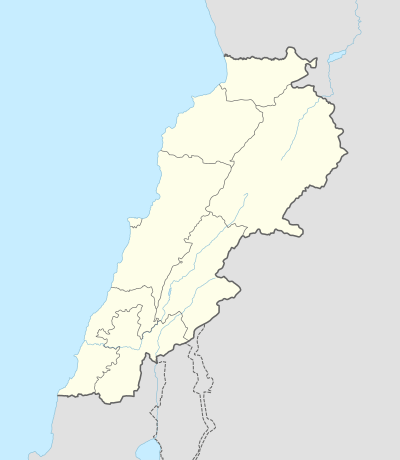

Shown within Lebanon | |

| Location | 26 kilometres (16 mi) northeast of Baalbek |

|---|---|

| Region | Bekaa Valley |

| Coordinates | 34.197317°N 36.352392°E |

| Type | Tells |

| Part of | Settlements |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 6910 to 6780 BC (from 3 limited samples) |

| Periods | PPNB |

| Cultures | Neolithic, Roman, Byzantine |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1966, 1969 |

| Archaeologists | Diana Kirkbride, Lorraine Copeland, Peter Wescombe |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Public access | Yes |

History

The Neolithic settlements represented at Labweh have been found dating to at least the 7th millennium BC. It has been suggested that it was known to the Egyptians as Lab'u, to the Assyrians as Laba'u and as Lebo-hamath to the Hebrews.[3] This has been associated with the "entrance of Hamath" mentioned in the Books of Kings[4] and the Book of Ezekiel, noted as the Northern border of King Solomon's territory,[5] but subsequently lost to the Syrians. Jeroboam II, king of Israel, is said to have "restored the territory of Israel from the entrance of Hamath to the Sea of the Arabah (the Dead Sea)".[6]

Labweh in the original Syriac tongue means "heart" or "center", it also has been suggested to come from the Arabic for "lion" or "lioness". The village has several archaeological sites of interest including three old caves with Roman-Byzantine sarcophagi and the remains of a temple. There are also remains of a Byzantine bastion and a Roman dam suggested to date to the reign of Queen Zenobia. Legend suggests that channels were carved through the rock to send water to her lands in Palmyra, Syria.[1]

Labweh Springs and Labweh River

The village is located on a hill 26 kilometres (16 mi) northeast of Baalbek, which gives its name to the Labweh Springs and Labweh River, one of the sources of the Orontes.[2] The Labweh river flows for approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) through rocky desert. It then cascades into a lake and wider stream at another village called Er-Ras, considered to be the source of the Orontes. This flows onwards northeast, fed by numerous other streams from Lebanon's mountains.[7][8]

Archaeological sites

Soundings and analysis of archaeological sites in Labweh were made by Lorraine Copeland and Peter Wescombe in 1966 with later excavations by Diana Kirkbride in 1969.[9] Tell Labweh, Tell Labweh South or Labweh I sits to the south of the village with another site to the north. The surface of Tell Labweh had been damaged by modern agriculture and it had been cut in half by road construction. Several burials were discovered inside the remains of rectangular buildings with white and red plaster floors. The remains of stone walls were found at lower levels and it is thought that the buildings may have used mud bricks at higher levels.[10]

Early neolithic finds included a large number of fragments of limestone White Ware or "Vaisselle Blanche", along with later pottery called dark faced burnished ware or DFBW. Only one vessel was reconstructed from the initial excavations; a bowl with combed finishing. Other shards included jars and bowls of a black, brown or red colour, one showed a straw wiped finish normally found in sites further South in the Jordan Valley. Others showed decorations such as chevrons, incised patterns and corded impressions.[10] Flints were similar to those found at Tell Ramad and included Byblos points, hooks, scrapers, borers and burins. Burials were found within two houses, which were excavated and found to be similar to those in earlier PPNB and PPNA sites. A range of sickle blades were found in the basal deposits and higher levels showing the evolution of denticulated and segmented cutting edges with similarities to those found at the oldest neolithic Byblos. Three initial samples were Radiocarbon dated suggesting a range of dates between 6780 and 6910 BC; a date range covering only c. 130 years.[11] The range of finds at the site has however helped to reveal some aspects of the transition through neolithic stages.[10]

Tell Labweh North is another large archaeological site, a few hundred metres north on the other side of the village and springs. Finely denticulated sickle blades, arrowheads and trapezoidal, flaked axes and fragments of white ware along with burnished pottery with patterns and a fragment of obsidian were collected from the surface of the site. Most of the finds indicated settlement around the time of Tell Labweh (South) and Byblos.[10] Fauna would have included forest animals and numerous domesticated cattle, sheep and goats.[12]

Roman temple

There are the ruins of a Roman temple in the village that are included in a group of Temples of the Beqaa Valley.[13]

It was a prostyle type but only one block of the western wall remained visible. Modern construction built a house inside the temple.[14] There are around twenty temples located between Labweh and Ain el-Baid.[15]

(The Roman temple was) converted into a fortress in a later era, the building blocks were used as reinforcements. A single section of the west wall remains in place, otherwise, only the podium (floor) of the temple is still visible.[16]

George F. Taylor divided up the Temples of Lebanon into three groups, one covering the Beqaa valley north of the road from Beirut to Damascus. Secondly a group to the south, including the Wadi al-Taym known as Temples of Mount Hermon. Thirdly a group in the area west of a line drawn along the ridge of Mount Lebanon.

The Temples of the Beqaa Valley in Taylor's first group included Labweh, Yammoune, Qasr Banat, Iaat, Nahle, Baalbek, Hadet, Kasr Neba, Temnin el-Foka, Nebi Ham, Saraain El Faouqa, Niha, Hosn Niha, Fourzol and Kafr Zebad.[17]

Literature

- Kirkbride, Diana., Early Byblos and the Bakaa, Volume 45 (Pages 43–60), Mélanges de l'Université Saint-Joseph (Beirut Lebanon), 1969.

- Copeland, Lorraine and Westcombe, Peter., Inventory of Stone Age Sites in Lebanon Part 2: North - South - East Central Lebanon Volume 42 (Pages 1–174) Mélanges de l'Université Saint-Joseph (Beirut Lebanon), 1966.

References

- Ba'albeck - Al-Hermal, Bekaa - Tourist Brochure

- Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain) (1837). The journal of the Royal Geographic Society of London. J. Murray. pp. 99–. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Mazar (Maisler), B. (1946). "Topographical Studies V: Lebo-Hamath and the Northern Boundary of Canaan". Bulletin of the Israel Exploration Society. 12: 91–102.

- 1 Kings 8:65

- Daniel Isaac Block (March 1998). The Book of Ezekiel: chapters 25-48. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 713–. ISBN 978-0-8028-2536-0. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- 2 Kings 14:25: NKJV translation; cf. NIV translation, which refers to the Dead Sea

- Sir. William Smith, LLD, Ed. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854)

- Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain) (1842). Penny cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. C. Knight. pp. 469–. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Zeidan Abdel-Kafi Kafafi (1982). The Neolithic of Jordan (East Bank). Papyrus Druck. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished PhD Thesis. pp. 192–198.

- University of Cologne - Radiocarbon Context Database

- Richard H. Meadow; Melinda A. Zeder (1978). Approaches to faunal analysis in the Middle East. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-87365-951-2. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- George Taylor (1967). The Roman temples of Lebanon: a pictorial guide. Dar el-Machreq Publishers. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Othmar Keel (1997). The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Eisenbrauns. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-1-57506-014-9. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Baal: Bulletin d'archéologie et d'architecture libanaises. Direction Générale des Antiquités. 2001. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Labweh, with photo

- George Taylor (1971). "The Roman temples of Lebanon: a pictorial guide". (Les temples romains au Liban; guide illustré). Dar el-Machreq Publishers

External links

- Lebwe temple on www.lebanon.com

- Laboueh, Localiban