Tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that can be played individually against a single opponent (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball covered with felt over or around a net and into the opponent's court. The object of the game is to maneuver the ball in such a way that the opponent is not able to play a valid return. The player who is unable to return the ball will not gain a point, while the opposite player will.

Roger Federer hitting a backhanded shot in 2012 | |

| Highest governing body | International Tennis Federation |

|---|---|

| First played | Between 1859 and 1865, Birmingham, England |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Team members | Singles or doubles |

| Mixed gender | Yes, separate tours & mixed doubles |

| Type | Outdoor or indoor |

| Equipment | Ball, Racket, Net |

| Venue | tennis court |

| Glossary | Glossary of tennis terms |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | part of Summer Olympic programme from 1896 to 1924 Demonstration sport in the 1968 and 1984 Summer Olympics Part of Summer Olympic programme since 1988 |

| Paralympic | part of Summer Paralympic programme since 1992 |

Tennis is an Olympic sport and is played at all levels of society and at all ages. The sport can be played by anyone who can hold a racket, including wheelchair users. The modern game of tennis originated in Birmingham, England, in the late 19th century as lawn tennis.[1] It had close connections both to various field (lawn) games such as croquet and bowls as well as to the older racket sport today called real tennis. During most of the 19th century, in fact, the term tennis referred to real tennis, not lawn tennis.

The rules of modern tennis have changed little since the 1890s. Two exceptions are that from 1908 to 1961 the server had to keep one foot on the ground at all times, and the adoption of the tiebreak in the 1970s. A recent addition to professional tennis has been the adoption of electronic review technology coupled with a point-challenge system, which allows a player to contest the line call of a point, a system known as Hawk-Eye.

Tennis is played by millions of recreational players and is also a popular worldwide spectator sport. The four Grand Slam tournaments (also referred to as the Majors) are especially popular: the Australian Open played on hard courts, the French Open played on red clay courts, Wimbledon played on grass courts, and the US Open also played on hard courts.

History

Predecessors

Historians believe that the game's ancient origin lay in 12th century northern France, where a ball was struck with the palm of the hand.[2] Louis X of France was a keen player of jeu de paume ("game of the palm"), which evolved into real tennis, and became notable as the first person to construct indoor tennis courts in the modern style. Louis was unhappy with playing tennis outdoors and accordingly had indoor, enclosed courts made in Paris "around the end of the 13th century".[3] In due course this design spread across royal palaces all over Europe.[3] In June 1316 at Vincennes, Val-de-Marne and following a particularly exhausting game, Louis drank a large quantity of cooled wine and subsequently died of either pneumonia or pleurisy, although there was also suspicion of poisoning.[4] Because of the contemporary accounts of his death, Louis X is history's first tennis player known by name.[4] Another of the early enthusiasts of the game was King Charles V of France, who had a court set up at the Louvre Palace.[5]

It was not until the 16th century that rackets came into use and the game began to be called "tennis", from the French term tenez, which can be translated as "hold!", "receive!" or "take!", an interjection used as a call from the server to his opponent.[6] It was popular in England and France, although the game was only played indoors where the ball could be hit off the wall. Henry VIII of England was a big fan of this game, which is now known as real tennis.[7] During the 18th and early 19th centuries, as real tennis declined, new racket sports emerged in England.[8]

The invention of the first lawn mower in 1830, in Britain, is believed to have been a catalyst, for the preparation of modern-style grass courts, sporting ovals, playing fields, pitches, greens, etc. This in turn led to the codification of modern rules for many sports, including lawn tennis, most football codes, lawn bowls and others.[9]

Origins of the modern game

Between 1859 and 1865 Harry Gem, a solicitor and his friend Augurio Perera developed a game that combined elements of racquets and the Basque ball game pelota, which they played on Perera's croquet lawn in Birmingham in England.[10][11] In 1872, along with two local doctors, they founded the world's first tennis club on Avenue Road, Leamington Spa.[12] This is where "lawn tennis" was used as a name of activity by a club for the first time. After Leamington, the second club to take up the game of lawn tennis appears to have been the Edgbaston Archery and Croquet Society, also in Birmingham.

In Tennis: A Cultural History, Heiner Gillmeister reveals that on December 8, 1874, British army officer Walter Clopton Wingfield wrote to Harry Gem, commenting that he (Wingfield) had been experimenting with his version of lawn tennis “for a year and a half”.[13] In December 1873, Wingfield designed and patented a game which he called sphairistikè (Greek: σφαιριστική, meaning "ball-playing"), and was soon known simply as "sticky" – for the amusement of guests at a garden party on his friend's estate of Nantclwyd Hall, in Llanelidan, Wales.[14] According to R. D. C. Evans, turfgrass agronomist, "Sports historians all agree that [Wingfield] deserves much of the credit for the development of modern tennis."[8][15] According to Honor Godfrey, museum curator at Wimbledon, Wingfield "popularized this game enormously. He produced a boxed set which included a net, poles, rackets, balls for playing the game – and most importantly you had his rules. He was absolutely terrific at marketing and he sent his game all over the world. He had very good connections with the clergy, the law profession, and the aristocracy and he sent thousands of sets out in the first year or so, in 1874."[16] The world's oldest annual tennis tournament took place at Leamington Lawn Tennis Club in Birmingham in 1874.[17] This was three years before the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club would hold its first championships at Wimbledon, in 1877. The first Championships culminated in a significant debate on how to standardise the rules.[16]

In the U.S. in 1874 Mary Ewing Outerbridge, a young socialite, returned from Bermuda with a sphairistikè set. She became fascinated by the game of tennis after watching British army officers play.[18] She laid out a tennis court at the Staten Island Cricket Club at Camp Washington, Tompkinsville, Staten Island, New York. The first American National championship was played there in September 1880. An Englishman named O.E. Woodhouse won the singles title, and a silver cup worth $100, by defeating Canadian I. F. Hellmuth.[19] There was also a doubles match which was won by a local pair. There were different rules at each club. The ball in Boston was larger than the one normally used in New York.

On 21 May 1881, the oldest nationwide tennis organization in the world[20] was formed, the United States National Lawn Tennis Association (now the United States Tennis Association) in order to standardize the rules and organize competitions.[21] The U.S. National Men's Singles Championship, now the US Open, was first held in 1881 at the Newport Casino, Newport, Rhode Island.[22] The U.S. National Women's Singles Championships were first held in 1887 in Philadelphia.[23]

Tennis also became popular in France, where the French Championships dates to 1891 although until 1925 it was open only to tennis players who were members of French clubs.[24] Thus, Wimbledon, the US Open, the French Open, and the Australian Open (dating to 1905) became and have remained the most prestigious events in tennis.[25][26] Together these four events are called the Majors or Slams (a term borrowed from bridge rather than baseball).[27]

In 1913, the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF), now the International Tennis Federation (ITF), was founded and established three official tournaments as the major championships of the day. The World Grass Court Championships were awarded to Great Britain. The World Hard Court Championships were awarded to France; the term "hard court" was used for clay courts at the time. Some tournaments were held in Belgium instead. And the World Covered Court Championships for indoor courts was awarded annually; Sweden, France, Great Britain, Denmark, Switzerland and Spain each hosted the tournament.[28] At a meeting held on 16 March 1923 in Paris, the title 'World Championship' was dropped and a new category of Official Championship was created for events in Great Britain, France, the United States, and Australia – today's Grand Slam events.[28][29] The impact on the four recipient nations to replace the ‘world championships’ with ‘official championships’ was simple in a general sense: each became a major nation of the federation with enhanced voting power and each now operated a major event.[28]

The comprehensive rules promulgated in 1924 by the ILTF, have remained largely stable in the ensuing eighty years, the one major change being the addition of the tiebreak system designed by Jimmy Van Alen.[30] That same year, tennis withdrew from the Olympics after the 1924 Games but returned 60 years later as a 21-and-under demonstration event in 1984. This reinstatement was credited by the efforts by the then ITF President Philippe Chatrier, ITF General Secretary David Gray and ITF Vice President Pablo Llorens, and support from IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch. The success of the event was overwhelming and the IOC decided to reintroduce tennis as a full medal sport at Seoul in 1988.[31][32]

The Davis Cup, an annual competition between men's national teams, dates to 1900.[33] The analogous competition for women's national teams, the Fed Cup, was founded as the Federation Cup in 1963 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the ITF.[34]

In 1926, promoter C. C. Pyle established the first professional tennis tour with a group of American and French tennis players playing exhibition matches to paying audiences.[26][35] The most notable of these early professionals were the American Vinnie Richards and the Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen.[26][36] Once a player turned pro he or she was no longer permitted to compete in the major (amateur) tournaments.[26]

In 1968, commercial pressures and rumors of some amateurs taking money under the table led to the abandonment of this distinction, inaugurating the Open Era, in which all players could compete in all tournaments, and top players were able to make their living from tennis. With the beginning of the Open Era, the establishment of an international professional tennis circuit, and revenues from the sale of television rights, tennis's popularity has spread worldwide, and the sport has shed its middle-class English-speaking image[37] (although it is acknowledged that this stereotype still exists).[37][38]

In 1954, Van Alen founded the International Tennis Hall of Fame, a non-profit museum in Newport, Rhode Island.[39] The building contains a large collection of tennis memorabilia as well as a hall of fame honouring prominent members and tennis players from all over the world. Each year, a grass court tournament and an induction ceremony honoring new Hall of Fame members are hosted on its grounds.

Equipment

Part of the appeal of tennis stems from the simplicity of equipment required for play. Beginners need only a racket and balls.

Rackets

The components of a tennis racket include a handle, known as the grip, connected to a neck which joins a roughly elliptical frame that holds a matrix of tightly pulled strings. For the first 100 years of the modern game, rackets were made of wood and of standard size, and strings were of animal gut. Laminated wood construction yielded more strength in rackets used through most of the 20th century until first metal and then composites of carbon graphite, ceramics, and lighter metals such as titanium were introduced. These stronger materials enabled the production of oversized rackets that yielded yet more power. Meanwhile, technology led to the use of synthetic strings that match the feel of gut yet with added durability.

Under modern rules of tennis, the rackets must adhere to the following guidelines;[40]

- The hitting area, composed of the strings, must be flat and generally uniform.

- The frame of the hitting area may not be more than 29 inches (74 cm) in length and 12.5 inches (32 cm) in width.

- The entire racket must be of a fixed shape, size, weight, and weight distribution. There may not be any energy source built into the rackets.

- The rackets must not provide any kind of communication, instruction or advice to the player during the match.

The rules regarding rackets have changed over time, as material and engineering advances have been made. For example, the maximum length of the frame had been 32 inches (81 cm) until 1997, when it was shortened to 29 inches (74 cm).[41]

Many companies manufacture and distribute tennis rackets. Wilson, Head and Babolat are some of the more commonly used brands; however, many more companies exist. The same companies sponsor players to use these rackets in the hopes that the company name will become more well known by the public.

Balls

Tennis balls were originally made of cloth strips stitched together with thread and stuffed with feathers.[42] Modern tennis balls are made of hollow vulcanized rubber with a felt coating. Traditionally white, the predominant colour was gradually changed to optic yellow in the latter part of the 20th century to allow for improved visibility. Tennis balls must conform to certain criteria for size, weight, deformation, and bounce to be approved for regulation play. The International Tennis Federation (ITF) defines the official diameter as 65.41–68.58 mm (2.575–2.700 in). Balls must weigh between 56.0 and 59.4 g (1.98 and 2.10 oz).[43] Tennis balls were traditionally manufactured in the United States and Europe. Although the process of producing the balls has remained virtually unchanged for the past 100 years, the majority of manufacturing now takes place in the Far East. The relocation is due to cheaper labour costs and materials in the region.[44] Tournaments that are played under the ITF Rules of Tennis must use balls that are approved by the International Tennis Federation (ITF) and be named on the official ITF list of approved tennis balls.[45]

Miscellaneous

Advanced players improve their performance through a number of accoutrements. Vibration dampeners may be interlaced in the proximal part of the string array for improved feel. Racket handles may be customized with absorbent or rubber-like materials to improve the players' grip. Players often use sweat bands on their wrists to keep their hands dry and head bands or bandanas to keep the sweat out of their eyes as well. Finally, although the game can be played in a variety of shoes, specialized tennis shoes have wide, flat soles for stability and a built-up front structure to avoid excess wear.

Manner of play

Court

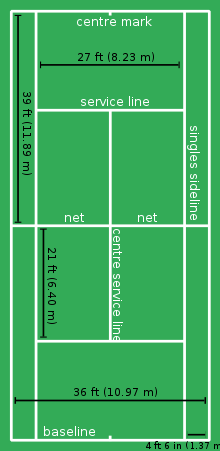

Tennis is played on a rectangular, flat surface. The court is 78 feet (23.77 m) long, and 27 feet (8.2 m) wide for singles matches and 36 ft (11 m) for doubles matches.[46] Additional clear space around the court is required in order for players to reach overrun balls. A net is stretched across the full width of the court, parallel with the baselines, dividing it into two equal ends. It is held up by either a cord or metal cable of diameter no greater than 0.8 cm (1⁄3 in).[47] The net is 3 feet 6 inches (1.07 m) high at the posts and 3 feet (0.91 m) high in the center.[46] The net posts are 3 feet (0.91 m) outside the doubles court on each side or, for a singles net, 3 feet (0.91 m) outside the singles court on each side.

The modern tennis court owes its design to Major Walter Clopton Wingfield. In 1873, Wingfield patented a court much the same as the current one for his stické tennis (sphairistike). This template was modified in 1875 to the court design that exists today, with markings similar to Wingfield's version, but with the hourglass shape of his court changed to a rectangle.[48]

Tennis is unusual in that it is played on a variety of surfaces.[49] Grass, clay, and hardcourts of concrete or asphalt topped with acrylic are the most common. Occasionally carpet is used for indoor play, with hardwood flooring having been historically used. Artificial turf courts can also be found.

Lines

The lines that delineate the width of the court are called the baseline (farthest back) and the service line (middle of the court). The short mark in the center of each baseline is referred to as either the hash mark or the center mark. The outermost lines that make up the length are called the doubles sidelines; they are the boundaries for doubles matches. The lines to the inside of the doubles sidelines are the singles sidelines, and are the boundaries in singles play. The area between a doubles sideline and the nearest singles sideline is called the doubles alley, playable in doubles play. The line that runs across the center of a player's side of the court is called the service line because the serve must be delivered into the area between the service line and the net on the receiving side. Despite its name, this is not where a player legally stands when making a serve.[50]

The line dividing the service line in two is called the center line or center service line. The boxes this center line creates are called the service boxes; depending on a player's position, they have to hit the ball into one of these when serving.[51] A ball is out only if none of it has hit the area inside the lines, or the line, upon its first bounce. All lines are required to be between 1 and 2 inches (25 and 51 mm) in width, with the exception of the baseline which can be up to 4 inches (100 mm) wide, although in practice it is often the same width as the others.[50]

Play of a single point

The players or teams start on opposite sides of the net. One player is designated the server, and the opposing player is the receiver. The choice to be server or receiver in the first game and the choice of ends is decided by a coin toss before the warm-up starts. Service alternates game by game between the two players or teams. For each point, the server starts behind the baseline, between the center mark and the sideline. The receiver may start anywhere on their side of the net. When the receiver is ready, the server will serve, although the receiver must play to the pace of the server.

For a service to be legal, the ball must travel over the net without touching it into the diagonally opposite service box. If the ball hits the net but lands in the service box, this is a let or net service, which is void, and the server retakes that serve. The player can serve any number of let services in a point and they are always treated as voids and not as faults. A fault is a serve that falls long or wide of the service box, or does not clear the net. There is also a "foot fault" when a player's foot touches the baseline or an extension of the center mark before the ball is hit. If the second service, after a fault, is also a fault, the server double faults, and the receiver wins the point. However, if the serve is in, it is considered a legal service.

A legal service starts a rally, in which the players alternate hitting the ball across the net. A legal return consists of a player hitting the ball so that it falls in the server's court, before it has bounced twice or hit any fixtures except the net. A player or team cannot hit the ball twice in a row. The ball must travel over the net into the other players' court. A ball that hits the net during a rally is considered a legal return as long as it crosses into the opposite side of the court. The first player or team to fail to make a legal return loses the point. The server then moves to the other side of the service line at the start of a new point.[52]

Scoring

Game, set, match

Game

A game consists of a sequence of points played with the same player serving. A game is won by the first player to have won at least four points in total and at least two points more than the opponent. The running score of each game is described in a manner peculiar to tennis: scores from zero to three points are described as "love", "15", "30", and "40", respectively. If at least three points have been scored by each player, making the player's scores equal at 40 apiece, the score is not called out as "40–40", but rather as "deuce". If at least three points have been scored by each side and a player has one more point than his opponent, the score of the game is "advantage" for the player in the lead. During informal games, "advantage" can also be called "ad in" or "van in" when the serving player is ahead, and "ad out" or "van out" when the receiving player is ahead; alternatively, either player may simply call out "my ad" or "your ad" during informal play.

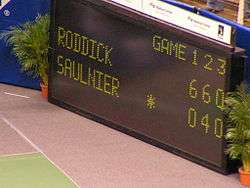

The score of a tennis game during play is always read with the serving player's score first. In tournament play, the chair umpire calls the point count (e.g., "15-love") after each point. At the end of a game, the chair umpire also announces the winner of the game and the overall score.

Set

A set consists of a sequence of games played with service alternating between games, ending when the count of games won meets certain criteria. Typically, a player wins a set by winning at least six games and at least two games more than the opponent. If one player has won six games and the opponent five, an additional game is played. If the leading player wins that game, the player wins the set 7–5. If the trailing player wins the game (tying the set 6–6) a tie-break is played. A tie-break, played under a separate set of rules, allows one player to win one more game and thus the set, to give a final set score of 7–6. A "love" set means that the loser of the set won zero games, colloquially termed a 'jam donut' in the US.[53] In tournament play, the chair umpire announces the winner of the set and the overall score. The final score in sets is always read with the winning player's score first, e.g. "6–2, 4–6, 6–0, 7–5".

Match

A match consists of a sequence of sets. The outcome is determined through a best of three or five sets system. On the professional circuit, men play best-of-five-set matches at all four Grand Slam tournaments, Davis Cup, and the final of the Olympic Games and best-of-three-set matches at all other tournaments, while women play best-of-three-set matches at all tournaments. The first player to win two sets in a best-of-three, or three sets in a best-of-five, wins the match.[54] Only in the final sets of matches at the French Open, the Olympic Games, and Fed Cup are tie-breaks not played. In these cases, sets are played indefinitely until one player has a two-game lead, occasionally leading to some remarkably long matches.

In tournament play, the chair umpire announces the end of the match with the well-known phrase "Game, set, match" followed by the winning person's or team's name.

Special point terms

Game point

A game point occurs in tennis whenever the player who is in the lead in the game needs only one more point to win the game. The terminology is extended to sets (set point), matches (match point), and even championships (championship point). For example, if the player who is serving has a score of 40-love, the player has a triple game point (triple set point, etc.) as the player has three consecutive chances to win the game. Game points, set points, and match points are not part of official scoring and are not announced by the chair umpire in tournament play.

Break point

A break point occurs if the receiver, not the server, has a chance to win the game with the next point. Break points are of particular importance because serving is generally considered advantageous, with servers being expected to win games in which they are serving. A receiver who has one (score of 30–40 or advantage), two (score of 15–40) or three (score of love-40) consecutive chances to win the game has break point, double break point or triple break point, respectively. If the receiver does, in fact, win their break point, the game is awarded to the receiver, and the receiver is said to have converted their break point. If the receiver fails to win their break point it is called a failure to convert. Winning break points, and thus the game, is also referred to as breaking serve, as the receiver has disrupted, or broken the natural advantage of the server. If in the following game the previous server also wins a break point it is referred to as breaking back. Except where tie-breaks apply, at least one break of serve is required to win a set (otherwise a two-game lead would never occur).

Rule variations

- No ad

- From 'No advantage'. Scoring method created by Jimmy Van Alen. The first player or doubles team to win four points wins the game, regardless of whether the player or team is ahead by two points. When the game score reaches three points each, the receiver chooses which side of the court (advantage court or deuce court) the service is to be delivered on the seventh and game-deciding point. Utilized by World Team Tennis professional competition, ATP tours, WTA tours, ITF Pro Doubles and ITF Junior Doubles.[55][56]

- Pro set

- Instead of playing multiple sets, players may play one "pro set". A pro set is first to 8 (or 10) games by a margin of two games, instead of first to 6 games. A 12-point tie-break is usually played when the score is 8–8 (or 10–10). These are often played with no-ad scoring.

- Match tie-break

- This is sometimes played instead of a third set. A match tie-break (also called super tie-break) is played like a regular tie-break, but the winner must win ten points instead of seven. Match tie-breaks are used in the Hopman Cup, Grand Slams (excluding Wimbledon) and the Olympic Games for mixed doubles; on the ATP (since 2006), WTA (since 2007) and ITF (excluding four Grand Slam tournaments and the Davis Cup) tours for doubles and as a player's choice in USTA league play.

- Fast4

- Fast4 is a shortened format that offers a "fast" alternative, with four points, four games and four rules: there are no advantage scores, lets are played, tie-breakers apply at three games all and the first to four games wins the set.

Another, however informal, tennis format is called Canadian doubles. This involves three players, with one person playing against a doubles team. The single player gets to utilize the alleys normally reserved only for a doubles team. Conversely, the doubles team does not use the alleys when executing a shot. The scoring is the same as for a regular game. This format is not sanctioned by any official body.

"Australian doubles", another informal and unsanctioned form of tennis, is played with similar rules to the Canadian doubles style, only in this version, players rotate court position after each game, each player taking a turn at playing alone against the other two. As such, each player plays doubles and singles over the course of a match, with the singles player always serving. Scoring styles vary, but one popular method is to assign a value of 2 points to each game, with the server taking both points if he or she holds serve and the doubles team each taking one if they break serve.

Wheelchair tennis can be played by able-bodied players as well as people who require a wheelchair for mobility. An extra bounce is permitted. This rule makes it possible to have mixed wheelchair and able-bodied matches. It is possible for a doubles team to consist of a wheelchair player and an able-bodied player (referred to as "one-up, one-down"), or for a wheelchair player to play against an able-bodied player. In such cases, the extra bounce is permitted for the wheelchair users only.

Officials

In most professional play and some amateur competition, there is an officiating head judge or chair umpire (usually referred to simply as the umpire), who sits in a raised chair to one side of the court. The umpire has absolute authority to make factual determinations. The umpire may be assisted by line judges, who determine whether the ball has landed within the required part of the court and who also call foot faults. There also may be a net judge who determines whether the ball has touched the net during service. The umpire has the right to overrule a line judge or a net judge if the umpire is sure that a clear mistake has been made.[57]

In past tournaments, line judges tasked with calling the serve were sometimes assisted by electronic sensors that beeped to indicate an out-of-bounds serve; one such system was called "Cyclops".[58] Cyclops has since largely been replaced by the Hawk-Eye system.[59][60] In professional tournaments using this system, players are allowed three unsuccessful appeals per set, plus one additional appeal in the tie-break to challenge close line calls by means of an electronic review. The US Open, Miami Masters, US Open Series, and World Team Tennis started using this challenge system in 2006 and the Australian Open and Wimbledon introduced the system in 2007.[61] In clay-court matches, such as at the French Open, a call may be questioned by reference to the mark left by the ball's impact on the court surface.

The referee, who is usually located off the court, is the final authority about tennis rules. When called to the court by a player or team captain, the referee may overrule the umpire's decision if the tennis rules were violated (question of law) but may not change the umpire's decision on a question of fact. If, however, the referee is on the court during play, the referee may overrule the umpire's decision. (This would only happen in Davis Cup or Fed Cup matches, not at the World Group level, when a chair umpire from a non-neutral country is in the chair).[57]

Ball boys and girls may be employed to retrieve balls, pass them to the players, and hand players their towels. They have no adjudicative role. In rare events (e.g., if they are hurt or if they have caused a hindrance), the umpire may ask them for a statement of what actually happened. The umpire may consider their statements when making a decision. In some leagues, especially junior leagues, players make their own calls, trusting each other to be honest. This is the case for many school and university level matches. The referee or referee's assistant, however, can be called on court at a player's request, and the referee or assistant may change a player's call. In unofficiated matches, a ball is out only if the player entitled to make the call is sure that the ball is out.

Junior tennis

In tennis, a junior is a player under 18 who is still legally protected by a parent or guardian. Players on the main adult tour who are under 18 must have documents signed by a parent or guardian. These players, however, are still eligible to play in junior tournaments.

The International Tennis Federation (ITF) conducts a junior tour that allows juniors to establish a world ranking and an Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) or Women's Tennis Association (WTA) ranking. Most juniors who enter the international circuit do so by progressing through ITF, Satellite, Future, and Challenger tournaments before entering the main circuit. The latter three circuits also have adults competing in them. Some juniors, however, such as Australian Lleyton Hewitt and Frenchman Gaël Monfils, have catapulted directly from the junior tour to the ATP tour by dominating the junior scene or by taking advantage of opportunities given to them to participate in professional tournaments.

In 2004, the ITF implemented a new rankings scheme to encourage greater participation in doubles, by combining two rankings (singles and doubles) into one combined tally.[62] Junior tournaments do not offer prize money except for the Grand Slam tournaments, which are the most prestigious junior events. Juniors may earn income from tennis by participating in the Future, Satellite, or Challenger tours. Tournaments are broken up into different tiers offering different amounts of ranking points, culminating with Grade A.

Leading juniors are allowed to participate for their nation in the Junior Fed Cup and Davis Cup competitions. To succeed in tennis often means having to begin playing at a young age. To facilitate and nurture a junior's growth in tennis, almost all tennis playing nations have developed a junior development system. Juniors develop their play through a range of tournaments on all surfaces, accommodating all different standards of play. Talented juniors may also receive sponsorships from governing bodies or private institutions.

Match play

Continuity

A tennis match is intended to be continuous.[63] Because stamina is a relevant factor, arbitrary delays are not permitted. In most cases, service is required to occur no more than 20 seconds after the end of the previous point.[63] This is increased to 90 seconds when the players change ends (after every odd-numbered game), and a 2-minute break is permitted between sets.[63] Other than this, breaks are permitted only when forced by events beyond the players' control, such as rain, damaged footwear, damaged racket, or the need to retrieve an errant ball. Should a player be deemed to be stalling repeatedly, the chair umpire may initially give a warning followed by subsequent penalties of "point", "game", and default of the match for the player who is consistently taking longer than the allowed time limit.[64]

In the event of a rain delay, darkness or other external conditions halting play, the match is resumed at a later time, with the same score as at the time of the delay, and each player at the same end of the court as when rain halted play, or as close to the same relative compass point if play is resumed on a different court.

Ball changes

Balls wear out quickly in serious play and, therefore, in ATP and WTA tournaments, they are changed after every nine games with the first change occurring after only seven games, because the first set of balls is also used for the pre-match warm-up.[43] In ITF tournaments like Fed Cup, the balls are changed after every eleven games (rather than nine) with the first change occurring after only nine games (instead of seven). An exception is that a ball change may not take place at the beginning of a tiebreaker, in which case the ball change is delayed until the beginning of the second game of the next set.[47] As a courtesy to the receiver, the server will often signal to the receiver before the first serve of the game in which new balls are used as a reminder that they are using new balls. Continuity of the balls' condition is considered part of the game, so if a re-warm-up is required after an extended break in play (usually due to rain), then the re-warm-up is done using a separate set of balls, and use of the match balls is resumed only when play resumes.

Stance

Stance refers to the way a player prepares themselves in order to best be able to return a shot. Essentially, it enables them to move quickly in order to achieve a particular stroke. There are four main stances in modern tennis: open, semi-open, closed, and neutral. All four stances involve the player crouching in some manner: as well as being a more efficient striking posture, it allows them to isometrically preload their muscles in order to play the stroke more dynamically. What stance is selected is strongly influenced by shot selection. A player may quickly alter their stance depending on the circumstances and the type of shot they intend to play. Any given stance also alters dramatically based upon the actual playing of the shot with dynamic movements and shifts of body weight occurring.[70][71]

Open stance

This is the most common stance in tennis. The player’s feet are placed parallel to the net. They may be pointing sideways, directly at the net or diagonally towards it. This stance allows for a high degree of torso rotation which can add significant power to the stroke. This process is sometimes likened to the coiling and uncoiling of a spring. i.e the torso is rotated as a means of preloading the muscular system in preparation for playing the stroke: this is the coiling phase. When the stroke is played the torso rotates to face forwards again, called uncoiling, and adds significant power to the stroke. A disadvantage of this stance is that it does not always allow ‘for proper weight transfer and maintenance of balance’[70] when making powerful strokes. It is commonly used for forehand strokes; double-handed backhands can also be made effectively from it.

Semi-open stance

This stance is somewhere between open and closed and is a very flexible stance. The feet are aligned diagonally towards the net. It allows for a lot of shoulder rotation and the torso can be coiled, before being uncoiled into the shot in order to increase the power of the shot. It is commonly used in modern tennis especially by ‘top professional players on the forehand’.[72] Two-handed backhands can also be employed from this stance.

Closed stance

The closed stance is the least commonly used of the three main stances. One foot is placed further towards the net with the other foot further from it; there is a diagonal alignment between the feet. It allows for effective torso rotation in order to increase the power of the shot. It is usually used to play backhand shots and it is rare to see forehand shots played from it. A stroke from this stance may entail the rear foot coming completely off the floor with bodyweight being transferred entirely to the front foot.[70] [71]

Neutral stance

This is sometimes also referred to as the square stance. One foot is positioned closer to the net and ahead of the other which is behind and in line with it. Both feet are aligned at a 90 degree angle to the net. The neutral stance is often taught early because ‘It allows beginners to learn about shifting weight and rotation of the body.’[71] Forehands and backhands may be made from it.[73]

Shots

A competent tennis player has eight basic shots in his or her repertoire: the serve, forehand, backhand, volley, half-volley, overhead smash, drop shot, and lob.

Grip

A grip is a way of holding the racket in order to hit shots during a match. The grip affects the angle of the racket face when it hits the ball and influences the pace, spin, and placement of the shot. Players use various grips during play, including the Continental (The "Handshake Grip"), Eastern (Can be either semi-eastern or full eastern. Usually used for backhands.), and Western (semi-western or full western, usually for forehand grips) grips. Most players change grips during a match depending on what shot they are hitting; for example, slice shots and serves call for a Continental grip.[74]

Serve

A serve (or, more formally, a "service") in tennis is a shot to start a point. The serve is initiated by tossing the ball into the air and hitting it (usually near the apex of its trajectory) into the diagonally opposite service box without touching the net. The serve may be hit under- or overhand although underhand serving remains a rarity.[75] If the ball hits the net on the first serve and bounces over into the correct diagonal box then it is called a "let" and the server gets two more additional serves to get it in. There can also be a let if the server serves the ball and the receiver isn't prepared.[47] If the server misses his or her first serve and gets a let on the second serve, then they get one more try to get the serve in the box.

Experienced players strive to master the conventional overhand serve to maximize its power and placement. The server may employ different types of serve including flat serve, topspin serve, slice serve, and kick (American twist) serve. A reverse type of spin serve is hit in a manner that spins the ball opposite the natural spin of the server, the spin direction depending upon right- or left-handedness. If the ball is spinning counterclockwise, it will curve right from the hitter's point of view and curve left if spinning clockwise.[76]

Some servers are content to use the serve simply to initiate the point; however, advanced players often try to hit a winning shot with their serve. A winning serve that is not touched by the opponent is called an "ace".

Forehand

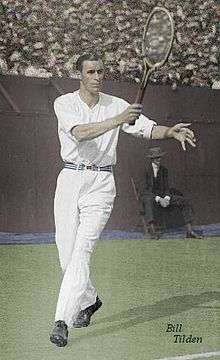

For a right-handed player, the forehand is a stroke that begins on the right side of the body, continues across the body as contact is made with the ball, and ends on the left side of the body. There are various grips for executing the forehand, and their popularity has fluctuated over the years. The most important ones are the continental, the eastern, the semi-western, and the western. For a number of years, the small, frail 1920s player Bill Johnston was considered by many to have had the best forehand of all time, a stroke that he hit shoulder-high using a western grip. Few top players used the western grip after the 1920s, but in the latter part of the 20th century, as shot-making techniques and equipment changed radically, the western forehand made a strong comeback and is now used by many modern players. No matter which grip is used, most forehands are generally executed with one hand holding the racket, but there have been fine players with two-handed forehands. In the 1940s and 50s, the Ecuadorian/American player Pancho Segura used a two-handed forehand to achieve a devastating effect against larger, more powerful players. Players such as Monica Seles or France's Fabrice Santoro and Marion Bartoli are also notable players known for their two-handed forehands.[77]

Backhand

For right-handed players, the backhand is a stroke that begins on the left side of their body, continues across their body as contact is made with the ball, and ends on the right side of their body. It can be executed with either one hand or with both and is generally considered more difficult to master than the forehand. For most of the 20th century, the backhand was performed with one hand, using either an eastern or a continental grip. The first notable players to use two hands were the 1930s Australians Vivian McGrath and John Bromwich, but they were lonely exceptions. The two-handed grip gained popularity in the 1970s as Björn Borg, Chris Evert, Jimmy Connors, and later Mats Wilander and Marat Safin used it to great effect, and it is now used by a large number of the world's best players, including Rafael Nadal and Serena Williams.[78]

Two hands give the player more control, while one hand can generate a slice shot, applying backspin on the ball to produce a low trajectory bounce. Reach is also limited with the two-handed shot. The player long considered to have had the best backhand of all time, Don Budge, had a powerful one-handed stroke in the 1930s and 1940s that imparted topspin onto the ball. Ken Rosewall, another player noted for his one-handed backhand, used a very accurate slice backhand through the 1950s and 1960s. A small number of players, notably Monica Seles, use two hands on both the backhand and forehand sides.

Other shots

A volley is a shot returned to the opponent in mid-air before the ball bounces, generally performed near the net, and is usually made with a stiff-wristed punching motion to hit the ball into an open area of the opponent's court. The half volley is made by hitting the ball on the rise just after it has bounced, also generally in the vicinity of the net, and played with the racket close to the ground.[79] The swinging volley is hit out of the air as the player approaches the net. It is an offensive shot used to take preparation time away from the opponent, as it returns the ball into the opponent's court much faster than a standard volley.

From a poor defensive position on the baseline, the lob can be used as either an offensive or defensive weapon, hitting the ball high and deep into the opponent's court to either enable the lobber to get into better defensive position or to win the point outright by hitting it over the opponent's head. If the lob is not hit deeply enough into the other court, however, an opponent near the net may then hit an overhead smash, a hard, serve-like shot, to try to end the point.

A difficult shot in tennis is the return of an attempted lob over the backhand side of a player. When the contact point is higher than the reach of a two-handed backhand, most players will try to execute a high slice (under the ball or sideways). Fewer players attempt the backhand sky-hook or smash. Rarely, a player will go for a high topspin backhand, while themselves in the air. A successful execution of any of these alternatives requires balance and timing, with less margin of error than the lower contact point backhands, since this shot is a break in the regular pattern of play.

If an opponent is deep in his court, a player may suddenly employ an unexpected drop shot, by softly tapping the ball just over the net so that the opponent is unable to run in fast enough to retrieve it. Advanced players will often apply back spin to a drop shot, causing the ball to "skid" upon landing and bounce sideways, with less forward momentum toward their opponent, or even backwards towards the net, thus making it even more difficult to return.

Injuries

Muscle strain is one of the most common injuries in tennis.[80] When an isolated large-energy appears during the muscle contraction and at the same time body weight apply huge amount of pressure to the lengthened muscle, muscle strain can occur.[81] Inflammation and bleeding are triggered when muscle strain occurs, which can result in redness, pain and swelling.[81] Overuse is also common in tennis players of all levels. Muscle, cartilage, nerves, bursae, ligaments and tendons may be damaged from overuse. The repetitive use of a particular muscle without time for repair and recovery is the most common cause of injury.[81]

Tournaments

Tournaments are often organized by gender and number of players. Common tournament configurations include men's singles, women's singles, and doubles, where two players play on each side of the net. Tournaments may be organized for specific age groups, with upper age limits for youth and lower age limits for senior players. Example of this include the Orange Bowl and Les Petits As junior tournaments. There are also tournaments for players with disabilities, such as wheelchair tennis and deaf tennis.[82] In the four Grand Slam tournaments, the singles draws are limited to 128 players for each gender.

Most large tournaments seed players, but players may also be matched by their skill level. According to how well a person does in sanctioned play, a player is given a rating that is adjusted periodically to maintain competitive matches. For example, the United States Tennis Association administers the National Tennis Rating Program (NTRP), which rates players between 1.0 and 7.0 in 1/2 point increments. Average club players under this system would rate 3.0–4.5 while world class players would be 7.0 on this scale.

Grand Slam tournaments

The four Grand Slam tournaments are considered to be the most prestigious tennis events in the world. They are held annually and comprise, in chronological order, the Australian Open, the French Open, Wimbledon, and the US Open. Apart from the Olympic Games, Davis Cup, Fed Cup, and Hopman Cup, they are the only tournaments regulated by the International Tennis Federation (ITF).[83] The ITF's national associations, Tennis Australia (Australian Open), the Fédération Française de Tennis (French Open), the Lawn Tennis Association (Wimbledon) and the United States Tennis Association (US Open) are delegated the responsibility to organize these events.[83]

Aside from the historical significance of these events, they also carry larger prize funds than any other tour event and are worth double the number of ranking points to the champion than in the next echelon of tournaments, the Masters 1000 (men) and Premier events (women).[84][85] Another distinguishing feature is the number of players in the singles draw. There are 128, more than any other professional tennis tournament. This draw is composed of 32 seeded players, other players ranked in the world's top 100, qualifiers, and players who receive invitations through wild cards. Grand Slam men's tournaments have best-of-five set matches while the women play best-of-three. Grand Slam tournaments are among the small number of events that last two weeks, the others being the Indian Wells Masters and the Miami Masters.

Currently, the Grand Slam tournaments are the only tour events that have mixed doubles contests. Grand Slam tournaments are held in conjunction with wheelchair tennis tournaments and junior tennis competitions. These tournaments also contain their own idiosyncrasies. For example, players at Wimbledon are required to wear predominantly white. Andre Agassi chose to skip Wimbledon from 1988 through 1990 citing the event's traditionalism, particularly its "predominantly white" dress code.[86] Wimbledon has its own particular methods for disseminating tickets, often leading tennis fans to follow complex procedures to obtain tickets.[87]

| Date | Tournament | Location | Surface | Prize Money | First Held |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January–February | Australian Open | Melbourne | Hard (Plexicushion) | A$55,000,000 (2018) | 1905 |

| May–June | French Open | Paris | Clay | €39,197,000 (2018) | 1891* |

| June–July | Wimbledon | London | Grass | £31,600,000 (2017) | 1877 |

| August–September | US Open | New York City | Hard (DecoTurf) | US$50,400,000 (2017) | 1881 |

* The international tournament began in 1925

Men's tournament structure

Masters 1000

The ATP World Tour Masters 1000 is a group of nine tournaments that form the second-highest echelon in men's tennis. Each event is held annually, and a win at one of these events is worth 1000 ranking points. When the ATP, led by Hamilton Jordan, began running the men's tour in 1990, the directors designated the top nine tournaments, outside of the Grand Slam events, as "Super 9" events.[88] In 2000 this became the Tennis Masters Series and in 2004 the ATP Masters Series. In November at the end of the tennis year, the world's top eight players compete in the ATP World Tour Finals, a tournament with a rotating locale. It is currently held in London, England.[89]

In August 2007 the ATP announced major changes to the tour that were introduced in 2009. The Masters Series was renamed to the "Masters 1000", the addition of the number 1000 referring to the number of ranking points earned by the winner of each tournament. Contrary to earlier plans, the number of tournaments was not reduced from nine to eight and the Monte Carlo Masters remains part of the series although, unlike the other events, it does not have a mandatory player commitment. The Hamburg Masters has been downgraded to a 500-point event. The Madrid Masters moved to May and onto clay courts, and a new tournament in Shanghai took over Madrid's former indoor October slot. As of 2011 six of the nine "1000" level tournaments are combined ATP and WTA events.[90]

250 and 500 Series

The third and fourth tier of men's tennis tournaments are formed by the ATP World Tour 500 series, consisting of 11 tournaments, and the ATP World Tour 250 series with 40 tournaments.[91] Like the ATP World Tour Masters 1000, these events offer various amounts of prize money and the numbers refer to the amount of ranking points earned by the winner of a tournament.[84] The Dubai Tennis Championships offer the largest financial incentive to players, with total prize money of US$2,313,975 (2012).[92] These series have various draws of 28, 32, 48 and 56 for singles and 16 and 24 for doubles. It is mandatory for leading players to enter at least four 500 events, including at least one after the US Open.

Challenger Tour and Futures tournaments

The Challenger Tour for men is the lowest level of tournament administered by the ATP. It is composed of about 150 events and, as a result, features a more diverse range of countries hosting events.[93] The majority of players use the Challenger Series at the beginning of their career to work their way up the rankings. Andre Agassi, between winning Grand Slam tournaments, plummeted to World No. 141 and used Challenger Series events for match experience and to progress back up the rankings.[94] The Challenger Series offers prize funds of between US$25,000 and US$150,000.

Below the Challenger Tour are the Futures tournaments, events on the ITF Men's Circuit. These tournaments also contribute towards a player's ATP rankings points. Futures Tournaments offer prize funds of between US$10,000 and US$15,000.[95] Approximately 530 Futures Tournaments are played each year.

Women's tournament structure

Premier events

Premier events for women form the most prestigious level of events on the Women's Tennis Association Tour after the Grand Slam tournaments. These events offer the largest rewards in terms of points and prize money. Within the Premier category are Premier Mandatory, Premier 5, and Premier tournaments. The Premier events were introduced in 2009 replacing the previous Tier I and II tournament categories. Currently four tournaments are Premier Mandatory, five tournaments are Premier 5, and twelve tournaments are Premier. The first tiering system in women's tennis was introduced in 1988. At the time of its creation, only two tournaments, the Lipton International Players Championships in Florida and the German Open in Berlin, comprised the Tier I category.

International events

International tournaments are the second main tier of the WTA tour and consist of 31 tournaments, with a prize money for every event at U.S.$220,000, except for the year-ending Commonwealth Bank Tournament of Champions in Bali, which has prize money of U.S.$600,000.

Players

Professional players

Professional tennis players enjoy the same relative perks as most top sports personalities: clothing, equipment and endorsements. Like players of other individual sports such as golf, they are not salaried, but must play and finish highly in tournaments to obtain prize money.

In recent years, some controversy has surrounded the involuntary or deliberate noise caused by players' grunting.

Singles and doubles professional careers

While players are gradually less competitive in singles by their late 20s and early 30s, they can still continue competitively in doubles (as instanced by Martina Navratilova and John McEnroe, who won doubles titles in their 40s).

In the Open Era, several female players such as Martina Navratilova, Margaret Court, Martina Hingis, Serena Williams, and Venus Williams (the latter two sisters playing together) have been prolific at both singles and doubles events throughout their careers. John McEnroe is one of the very few professional male players to be top ranked in both singles and doubles at the same time,[96][97][98] and Yevgeny Kafelnikov is the most recent male player to win multiple Grand Slams in both singles and doubles during the same period of his career.

In terms of public attention and earnings (see below), singles champions have far surpassed their doubles counterparts. The Open Era, particularly the men's side, has seen many top-ranked singles players that only sparingly compete in doubles, while having "doubles specialists" who are typically being eliminated early in the singles draw but do well in the doubles portion of a tournament. Notable doubles pairings include The Woodies (Todd Woodbridge and Mark Woodforde) and the Bryan Brothers (identical twin brothers Robert Charles "Bob" Bryan and Michael Carl "Mike" Bryan). Woodbridge has disliked the term "doubles ‘specialists’", saying that he and Woodforde "set a singles schedule and doubles fitted in around that", although later in Woodbridge's career he focused exclusively on doubles as his singles ranking fell too low that it was no longer financially viable to recover at that age. Woodbridge noted that while top singles players earn enough that they don't need to nor want to play doubles, he suggested that lower-ranked singles players outside the Top Ten should play doubles to earn more playing time and money.[99][100]

Olympics

The Olympics doubles tennis tournament necessitates that both members of a doubles pairing be from the same country, hence several top professional pairs such as Jamie Murray and Bruno Soares cannot compete in the Olympics. Top-ranked singles players that are usually rivals on the professional circuit, such as Boris Becker and Michael Stich, and Roger Federer and Stan Wawrinka have formed a rare doubles partnership for the Olympics. Unlike professional tennis tournaments (see below) where singles players receive much more prize money than doubles players, an Olympic medal for both singles and doubles has similar prestige. The Olympics is more of a priority for doubles champions while singles champions often skip the tournament.[99][100] While the ATP has voted for Olympic results to count towards player ranking points, WTA players voted against it.[101]

For the 2000 Olympics, Lisa Raymond was passed over for Team USA in favor of Serena Williams by captain Billie Jean King, even though Raymond was the top-ranked doubles player in the world at the time, and Raymond unsuccessfully challenged the selection.[101]

Prize money

In professional tennis tournaments such as Wimbledon, the singles competition receives the most prize money and coverage, followed by doubles, and then mixed doubles usually receive the lowest monetary awards.[102] For instance in the US Open as of 2018, the men's and women's singles prize money (US$40,912,000) accounts for 80.9 percent of total player base compensation, while men's and women's doubles (US$6,140,840), men's and women's singles qualifying (US$3,008,000), and mixed doubles (US$505,000) account for 12.1 percent, 5.9 percent, and 1.0 percent, respectively. The singles winner receives US$3,800,000, while the doubles winning pair receives $700,000 and the mixed doubles winning pair receives US$155,000.[103]

Grand Slam tournament winners

The following players have won at least five singles titles at Grand Slam tournaments:

- Active players in bold

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Greatest male players

A frequent topic of discussion among tennis fans and commentators is who was the greatest male singles player of all time. By a large margin, an Associated Press poll in 1950 named Bill Tilden as the greatest player of the first half of the 20th century.[104] From 1920 to 1930, Tilden won singles titles at Wimbledon three times and the U.S. Championships seven times. In 1938, however, Donald Budge became the first person to win all four major singles titles during the same calendar year, the Grand Slam, and won six consecutive major titles in 1937 and 1938. Tilden called Budge "the finest player 365 days a year that ever lived."[105] In his 1979 autobiography, Jack Kramer said that, based on consistent play, Budge was the greatest player ever.[106] Some observers, however, also felt that Kramer deserved consideration for the title. Kramer was among the few who dominated amateur and professional tennis during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Tony Trabert has said that of the players he saw before the start of the Open Era, Kramer was the best male champion.[107]

By the 1960s, Budge and others had added Pancho Gonzales and Lew Hoad to the list of contenders. Budge reportedly believed that Gonzales was the greatest player ever.[108] Gonzales said about Hoad, "When Lew's game was at its peak nobody could touch him. ... I think his game was the best game ever. Better than mine. He was capable of making more shots than anybody. His two volleys were great. His overhead was enormous. He had the most natural tennis mind with the most natural tennis physique."[109]

Before and during the Open Era, Rod Laver remains the only male player in history to have won the calendar year Grand Slam twice in 1962 and 1969 [110] and also the calendar year Professional Grand Slam in 1967.[111] More recently Björn Borg and Pete Sampras were regarded by many of their contemporaries as among the greatest ever. Andre Agassi, the first of two male players in history to have achieved a Career Golden Slam in singles tennis (followed by Rafael Nadal), has been called the best service returner in the history of the game.[112][113][114][115] He is the first man to win grand slams on all modern surfaces (previous holders of all grand slam tournaments played in an era of grass and clay only), and is regarded by a number of critics and fellow players to be among the greatest players of all time.[112][116][117] Both Rod Laver and Ken Rosewall also won major Pro Slam tournaments on all three surfaces (grass, clay, hard court) Rosewall in 1963 and Laver in 1967.[118]

By the early twenty-first century, Roger Federer is considered by many observers to have the most "complete" game in modern tennis. He has won 20 grand slam titles and 6 World Tour Finals, the most for any male player. Many experts of tennis, former tennis players and his own tennis peers believe Federer is the greatest player in the history of the game.[119][120][121][122][123][124] Federer's biggest rival Rafael Nadal is regarded as the greatest competitor in tennis history by some former players and is regarded to have the potential to be the greatest of all time.[125][126] Nadal is regarded as the greatest clay court player of all time.[127] Novak Djokovic, a rival of both Nadal and Federer, is also considered to be one of the greatest tennis players of all time.[128]

Greatest female players

As with the men there are frequent discussions about who is the greatest female singles player of all time with Steffi Graf, Martina Navratilova and Serena Williams being the three players most often nominated.

In March 2012 the TennisChannel published a combined list of the 100 greatest men and women tennis players of all time.[129] It ranked Steffi Graf as the greatest female player (in 3rd place overall), followed by Martina Navratilova (4th place) and Margaret Court (8th place). The rankings were determined by an international panel.

Sportswriter John Wertheim of Sports Illustrated stated in an article in July 2010 that Serena Williams is the greatest female tennis player ever with the argument that "Head-to-head, on a neutral surface (i.e. hard courts), everyone at their best, I can't help feeling that she crushes the other legends.".[130] In a reaction to this article Yahoo sports blog Busted Racket published a list of the top-10 women's tennis players of all time placing Martina Navratilova in first spot.[131] This top-10 list was similar to the one published in June 2008 by the Bleacher Report who also ranked Martina Navratilova as the top female player of all time.[132]

Steffi Graf is considered by some to be the greatest female player. Billie Jean King said in 1999, "Steffi is definitely the greatest women's tennis player of all time."[133] Martina Navratilova has included Graf on her list of great players.[133] In December 1999, Graf was named the greatest female tennis player of the 20th century by a panel of experts assembled by the Associated Press.[134] Tennis writer Steve Flink, in his book The Greatest Tennis Matches of the Twentieth Century, named her as the best female player of the 20th century, directly followed by Martina Navratilova.[135]

Tennis magazine selected Martina Navratilova as the greatest female tennis player for the years 1965 through 2005.[136][137] Tennis historian and journalist Bud Collins has called Navratilova "arguably, the greatest player of all time."[138] Billie Jean King said about Navratilova in 2006, "She's the greatest singles, doubles and mixed doubles player who's ever lived."[139]

In popular culture

- "Tennis balles" are mentioned by William Shakespeare in his play Henry V (1599), when a basket of them is given to King Henry as a mockery of his youth and playfulness.

- David Foster Wallace, an amateur tennis player himself at Urbana High School in Illinois,[140] included tennis in many of his works of nonfiction and fiction including "Tennis Player Michael Joyce's Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff about Choice, Freedom, Discipline, Joy, Grotesquerie, and Human Completeness," the autobiographical piece "Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley," and Infinite Jest, which is partially set at the fictional "Enfield Tennis Academy" in Massachusetts.

- Japanese Manga series The Prince of Tennis revolves around the tennis prodigy Echizen Ryoma and tennis matches between rival schools.

- The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) features Richie Tenenbaum (Luke Wilson), a tennis pro who suffers from depression and has a breakdown on court in front of thousands of fans.[141]

- Wimbledon (2004) is a film about a discouraged pro tennis player (Paul Bettany) who meets a young woman on the women's tennis circuit (Kirsten Dunst) who helps him find his drive to go and win Wimbledon.[142]

- In The Squid and the Whale (2005), Joan (Laura Linney) has an affair with her kids' tennis coach, Ivan (William Baldwin). In a symbolic scene, Joan's ex-husband, Bernard (Jeff Daniels), loses a tennis match against Ivan in front of the kids.[143]

- Woody Allen's Match Point (2005) features a love affair between a former tennis pro, Chris Wilton (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), and his best friend's fiancé, Nola Rice (Scarlett Johansson). A scene of the movie includes a brief comparison between Andre Agassi and Tim Henman, with Chris Wilton calling both of them "geniuses".[144]

- Confetti (2006) is a mockumentary which sees three couples competing to win the title of "Most Original Wedding of the Year". One competing couple (Meredith MacNeill and Stephen Mangan) are a pair of hyper-competitive professional tennis players holding a tennis-themed wedding.[145]

- There are several tennis video games including the Mario Tennis series, the TopSpin series, the Virtua Tennis series, Sega Superstars Tennis, Grand Slam Tennis and Wii Sports.[146][147]

See also

References

- William J. Baker (1988). "Sports in the Western World". p. 182. University of Illinois Press,

- Gillmeister, Heiner (1998). Tennis : A Cultural History. Washington Square, N.Y.: New York University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-8147-3121-X.

- Newman, Paul B. (2001). Daily life in the Middle Ages. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-7864-0897-9.

- Gillmeister, Heiner (1998). Tennis : A Cultural History (Repr. ed.). London: Leicester University Press. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-0-7185-0195-2.

- John Moyer Heathcote; C. G. Heathcote; Edward Oliver Pleydell-Bouverie; Arthur Campbell Ainger (1901). Tennis. p. 14.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. 10 June 1927. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Crego, Robert. Sports and Games of the 18th and 19th Centuries, page 115 (2003).

- J. Perris (2000) Grass tennis courts: how to construct and maintain them p.8. STRI, 2000

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Radio National Ockham's Razor, first broadcast 6 June 2010.

- Tyzack, Anna, The True Home of Tennis Country Life, 22 June 2005

- "The Harry Gem Project". theharrygemproject.co.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Leamington Tennis Club". Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- "Leamington Tennis Court Club".

- E. M. Halliday. "Sphairistiké, Anyone?". American Heritage. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- Major Walter Clopton Wingfield International Tennis Hall of Fame. Retrieved 24 September 2011

- "125 years of Wimbledon: From birth of lawn tennis to modern marvels". CNN. Retrieved 21 September 2011

- [Tennis: A Cultural History by Heiner Gillmeister]

- Grimsley, Will (1971). Tennis: Its History, People and Events. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. p. 9. ISBN 0-13-903377-7.

- "Lawn-Tennis on Staten Island" (PDF). The New York Times. 4 September 1880. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- [Heiner Gillmeister Tennis: A Cultural History]

- "History of United States Tennis Association". Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- "Fact & History". Rhodes Island Government. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- "History of the U.S. National Championships/US Open". USOpen.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "History of the French Open". Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- "History of Tennis". International Tennis Federation. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- "Suzanne Lenglen and the First Pro Tour". Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- "Originality of the phrase "Grand Slam"". Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- Bensen, Clark (2013–2014). "The World Championships of 1913 to 1923: the Forgotten Majors" (PDF). tenniscollectors.org. Newport, RI, United States: Journal of The Tennis Collectors of America. p. 470. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

Number 30

CS1 maint: date format (link) - "ITF: History". ITF Tennis. London, United Kingdom: International Tennis Federation. 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "James Henry Van Alen in the Tennis Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- "Olympic Tennis Event". ITF. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "The Tennis and Olympics Love Affair". SportsPundit.com. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Davis Cup History". ITF. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Fed Cup History". ITF. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "History of the Pro Tennis Wars Chapter 2, part 1 1927–1928". Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- Open Minded Archived 31 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Bruce Goldman

- Henderson, Jon (10 December 2008). "Middle-class heroes can lift our game". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- Kate Magee (10 July 2008). "Max Clifford to help shed tennis' middle-class image". PR Week. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- "International Tennis Hall of Fame Information". Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- "ITF Tennis – Technical – Appendix II". ITF. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "ITF Tennis – Technical – The Racket". ITF. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Grimsley, Will (1971). Tennis: Its History, People and Events: Styles of the Greats. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 14. ISBN 0-13-903377-7.

- "History of Rule 3 – The Ball". ITF. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- "Balls- Manufacture". ITF. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- "ITF Rules of Tennis" (PDF). International Tennis Federation. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Tennis court dimensions". Sportsknowhow.com. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- International Tennis Federation. "ITF Rules of Tennis" (PDF). United States Tennis Association Website. USTA. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- "Tennis court history – Grass". ITF. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- "Surface Descriptions". International Tennis Federation. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "ITF Rules of Tennis – Rule 1 (The Court)" (PDF). ITF. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "ITF Rules of Tennis – Rule 17 (Serving)" (PDF). ITF. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Tennis Terminology". cbs.com. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- "ATP Most Jam Donuts Served". Tennis.com. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- From 1984 through 1998, women played first-to-win-three-sets in the final of the year-ending WTA Tour Championships.

- "WTT Firsts & Innovations". WTT.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Alternative Procedures and Scoring Methods". ITF. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "ITF Rules of Tennis – Appendix V (Role of Court Officials)" (PDF). ITF. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Cyclops and speed guns". BBC. 20 June 2003. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Cyclops knocked off centre as Wimbledon adopts Hawkeye". The Guardian. London. 24 April 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Evans, Richard (27 June 2009). "Hawk-eye Vision". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "The History Of Hawk-Eye". WTA Tour. 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "ITF Announce Combined Junior Rankings" (PDF). ITF. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "The ITF states this in Rule No. 29" (PDF).

- "Code of Conduct for 2012 ITF Pro Circuits Tournaments" (PDF). ITF. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

The first violation of this Section shall be penalised by a Time Violation warning and each subsequent violation shall be penalised by the assessment of one Time Violation point penalty.

- "Tennis On-Court Coaching". Expert-tennis-tips.com.

- "Coaching during a match". USTA. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Tennis Coaching Debate". NPR. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Does on-court coaching have a future?". ESPN. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- WTA 2012 Official Rulebook Chapter XVII/H

- "Tennis Stances". Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Tennis Techniques for Beginners". Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Tennis Stances". Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Tennis Footwork: Different Hitting Stances Explained". 27 March 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Grip Guide — A Grip on Your Game". Tennis.com. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Chang refused to lose 20 years ago". ESPN.com. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Serves". BBC. 12 September 2005. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "The Two-handed Forehand Revisited". TennisONE. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Damir Popadic. "Two-Handed is Superior to One-Handed Backhand" (PDF). ITF. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Grasso, John (2011). Historical Dictionary of Tennis. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8108-7237-0.

- Abrams, Geoffrey D.; Renstrom, Per A.; Safran, Marc R. (1 June 2012). "Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injury in the tennis player". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 46 (7): 492–498. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091164. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 22554841.

- Levangie, P. K., & Norkin, C. C. (2011). Joint structure and function: A comprehensive analysis (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co. ISBN 9780803623620.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Lawn Tennis Association Deaf tennis". Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "Grand Slams Overview". ITF. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "ATP Rankings FAQ". ATP. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "WTA Tour Rankings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- Sarah Holt (15 June 2005). "What not to wear at Wimbledon". BBC Sport. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "10 Ways to Grab a Seat at Wimbledon 2010". Wimbledondebentureholders.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- "History of Tennis". Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "London to host World Tour Final". BBC Sport, Piers Newbery. 3 July 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "ATP Tour 2009". Coretennis.net. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- "ATP World Tour Season". ATP. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships". ATP. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "About the Challenger Circuit". Association of Tennis Professionals. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "An appreciation of Andre Agassi". ESPN, Matt Wilansky. 1 July 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- "About the ITF Men's Circuit". International Tennis Federation. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- Rubinstein, Julian (30 January 2000). "Being John McEnroe". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "John McEnroe". International Tennis Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Cronin, Matthew (10 March 2011). Epic: John McEnroe, Bjorn Borg, and the Greatest Tennis Season Ever. Wiley. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-118-01595-7.

- "Doubles specialists face unusual pressure, atmosphere in Olympic tennis". Tennis.com.

- "Woodbridge: Doubles 'specialists' or tennis players?". Tennismash. 14 March 2017.

- "Raymond Is Taking Issue With a Doubles Standard". Los Angeles Times. 6 August 2000.

- "Wimbledon Prize Money". Associated Press. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- "2018 US Open Prize Money". United States Tennis Association. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "ESPN.com: Tilden brought theatrics to tennis". www.espn.com.

- "Don Budge's Comments After 1937 Davis Cup Semi-final Match Against Baron Gottfried von Cramm (1:07)". Archived from the original on 26 April 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- Kramer, Jack; Deford, Frank (1979). The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis. ISBN 0-399-12336-9.

- Richard Pagliaro (26 February 2004). "The Tennis Week Interview: Tony Trabert Part II". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- Will Grimsley, Tennis: Its History, People, and Events (1971)

- "Hoad" (PDF). Jame Buddell. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- Sclink, Leo (20 January 2012). "Rod Laver's priceless Grand Slam". Herald Sun. Australia. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- Bercow, John (2014). "Chapter 9: Rod Laver". Tennis Maestros: The Twenty Greatest Male Tennis Players of All Time. London, England: Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84954-765-9.

- Molinaro, John. "CBC Sports: "Tennis's love affair with Agassi comes to an end"". Cbc.ca. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "Reed's shotmakers: Men's return of serve". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Adjectives Tangled in the Net". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Dwyre, Bill (14 March 1995). "Sampras, Agassi Have Just Begun to Fight". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Parsons, John (26 June 2002). "Grand-slammed". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 6 May 2012.