Hawk-Eye

Hawk-Eye is a computer system used in numerous sports such as cricket, tennis, Gaelic football, badminton, hurling, rugby union, association football and volleyball, to visually track the trajectory of the ball and display a profile of its statistically most likely path as a moving image.[1] The onscreen representation of the trajectory results is called Shot Spot.[2]

The Sony-owned Hawk-Eye system was developed in the United Kingdom by Paul Hawkins. The system was originally implemented in 2001 for television purposes in cricket. The system works via six (sometimes seven) high-performance cameras, normally positioned on the underside of the stadium roof, which track the ball from different angles. The video from the six cameras is then triangulated and combined to create a three-dimensional representation of the ball's trajectory. Hawk-Eye is not infallible, but is accurate to within 3.6 millimetres and generally trusted as an impartial second opinion in sports.[3] It has been accepted by governing bodies in tennis, cricket and association football as a means of adjudication. Hawk-Eye is used for the Challenge System since 2006 in tennis and Umpire Decision Review System in cricket since 2009. The system was rolled out for the 2013–14 Premier League season as a means of goal-line technology.[4] In December 2014 the clubs of the first division of Bundesliga decided to adopt this system for the 2015–16 season.[5]

Method of operation

All Hawk-Eye systems are based on the principles of triangulation using visual images and timing data provided by a number of high-speed video cameras located at different locations and angles around the area of play.[6] For tennis there are ten cameras. The system rapidly processes the video feeds from the cameras and ball tracker. A data store contains a predefined model of the playing area and includes data on the rules of the game.

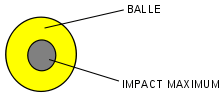

In each frame sent from each camera, the system identifies the group of pixels which corresponds to the image of the ball. It then calculates for each frame the position of the ball by comparing its position on at least two of the physically separate cameras at the same instant in time. A succession of frames builds up a record of the path along which the ball has travelled. It also "predicts" the future flight path of the ball and where it will interact with any of the playing area features already programmed into the database. The system can also interpret these interactions to decide infringements of the rules of the game.[6]

The system generates a graphic image of the ball path and playing area, which means that information can be provided to judges, television viewers or coaching staff in near real-time.

The tracking system is combined with a back-end database and archiving capabilities so that it is possible to extract and analyse trends and statistics about individual players, games, ball-to-ball comparisons, etc.

Hawk-Eye Innovations Ltd

Engineers at Roke Manor Research Limited, then a Siemens subsidiary in Romsey, England, developed the system in 2001. Paul Hawkins and David Sherry submitted a patent for the United Kingdom but withdrew their request.[6] All of the technology and intellectual property was spun off into a separated company, Hawk-Eye Innovations Ltd, based in Winchester, Hampshire.

On 14 June 2006 a group of investors—led by the Wisden Group and that included Mark Getty, a member of the wealthy American family and business dynasty— bought the company. The acquisition was intended to strengthen Wisden's presence in cricket and allow it to enter tennis and other international sports, with Hawk-Eye working on implementing a system for basketball. According to Hawk-Eye's website, the system produces much more data than that shown on television.

Put up for sale in September 2010, it was sold as a complete entity to Japanese electronic giant Sony in March 2011.[7][8]

Deployment in sports

Cricket

The technology was first used by Channel 4 during a Test match between England and Pakistan on Lord's Cricket Ground, on 21 May 2001. It is used primarily by the majority of television networks to track the trajectory of balls in flight. In the winter season of 2008/2009 the ICC trialled a referral system where Hawk-Eye was used for referring decisions to the third umpire if a team disagreed with an LBW decision. The third umpire was able to look at what the ball actually did up to the point when it hit the batsman, but could not look at the predicted flight of the ball after it hit the batsman.[9]

Its major use in cricket broadcasting is in analysing leg before wicket decisions, where the likely path of the ball can be projected forward, through the batsman's legs, to see if it would have hit the stumps. Consultation of the third umpire, for conventional slow motion or Hawk-Eye, on leg before wicket decisions, is currently sanctioned in international cricket even though doubts remain about its accuracy.[10]

The Hawk-Eye referral for a LBW decision is based on three criteria:

- Where the ball pitched

- The location of impact with the leg of the batsman

- The projected path of the ball past the batsman

In all three cases, marginal calls result in the on-field call being maintained.

Due to its real-time coverage of bowling speed, the systems are also used to show delivery patterns of a bowler's behaviour such as line and length, or swing/turn information. At the end of an over, all six deliveries are often shown simultaneously to illustrate a bowler's variations, such as slower deliveries, bouncers and leg-cutters. A complete record of a bowler can also be shown over the course of a match.

Batsmen also benefit from the analysis of Hawk-Eye, as a record can be brought up of the deliveries from which a batsman scored. These are often shown as a 2-D silhouetted figure of a batsman and colour-coded dots of the balls faced by the batsman. Information such as the exact spot where the ball pitches or speed of the ball from the bowler's hand (to gauge batsman reaction time) can also help in post-match analysis.

Tennis

.jpg)

In Serena Williams's quarter final loss to Jennifer Capriati at the 2004 US Open, three line calls went against Williams in the final set, and Auto-Ref system was being tested during the match. Though the calls were not reversed, there was one overrule of a clearly correct call by the chair umpire Mariana Alves that the TV replay showed to be good. These errors prompted talks about line calling assistance especially as the Auto-Ref system was being tested by the U.S. Open at that time and was shown to be very accurate.[11]

In late 2005 Hawk-Eye was tested by the International Tennis Federation (ITF) in New York City and was passed for professional use. Hawk-Eye reported that the New York tests involved 80 shots being measured by the ITF's high speed camera, a device similar to MacCAM. During an early test of the system at an exhibition tennis tournament in Australia (seen on local TV), there was an instance when the tennis ball was shown as "Out", but the accompanying word was "In". This was explained to be an error in the way the tennis ball was shown on the graphical display as a circle, rather than as an ellipse. This was immediately corrected.

Hawk-Eye has been used in television coverage of several major tennis tournaments, including Wimbledon, the Queen's Club Championships, the Australian Open, the Davis Cup and the Tennis Masters Cup. The US Open Tennis Championship announced they would make official use of the technology for the 2006 US Open where each player receives two challenges per set.[12] It is also used as part of a larger tennis simulation implemented by IBM called PointTracker.

The 2006 Hopman Cup in Perth, Western Australia, was the first elite-level tennis tournament where players were allowed to challenge point-ending line calls, which were then reviewed by the referees using Hawk-Eye technology. It used 10 cameras feeding information about ball position to the computers. Jamea Jackson was the first player to challenge a call using the system.

In March 2006, at the Nasdaq-100 Open in Miami, Hawk-Eye was used officially for the first time at a tennis tour event. Later that year, the US Open became the first grand-slam event to use the system during play, allowing players to challenge line calls.

The 2007 Australian Open was the first grand-slam tournament of 2007 to implement Hawk-Eye in challenges to line calls, where each tennis player in Rod Laver Arena was allowed two incorrect challenges per set and one additional challenge should a tiebreaker be played. In the event of an advantage final set, challenges were reset to two for each player every 12 games, i.e. 6 all, 12 all. Controversies followed the event as at times Hawk-Eye produced erroneous output. In 2008, tennis players were allowed three incorrect challenges per set instead. Any leftover challenges did not carry over to the next set. Once, Amélie Mauresmo challenged a ball that was called in, and Hawk-Eye showed the ball was out by less than a millimetre, but the call was allowed to stand. As a result, the point was replayed and Mauresmo did not lose an incorrect challenge.

The Hawk-Eye technology used in the 2007 Dubai Tennis Championships had some minor controversies. Defending champion Rafael Nadal accused the system of incorrectly declaring an out ball to be in following his exit. The umpire had called a ball out; when Mikhail Youzhny challenged the decision, Hawk-Eye said it was in by 3 mm.[13] Youzhny said after that he himself thought the mark may have been wide but then offered that this kind of technology error could easily have been made by linesmen and umpires. Nadal could only shrug, saying that had this system been on clay, the mark would have clearly shown Hawk-Eye to be wrong.[14] The area of the mark left by the ball on hard court is a portion of the total area that the ball was in contact with the court (a certain amount of pressure is required to create the mark) .

The 2007 Wimbledon Championships also implemented the Hawk-Eye system as an officiating aid on Centre Court and Court 1, and each tennis player was allowed three incorrect challenges per set. If the set produced a tiebreaker, each player was given an additional challenge. Additionally, in the event of a final set (third set in women's or mixed matches, fifth set in men's matches), where there is no tiebreak, each player's number of challenges was reset to three if the game score reached 6–6, and again at 12–12. Teymuraz Gabashvili, in his first round match against Roger Federer, made the first-ever Hawk-Eye challenge on Centre Court. Additionally, during the finals of Federer against Rafael Nadal, Nadal challenged a shot which was called out. Hawk-Eye showed the ball as in, just clipping the line. The reversal agitated Federer enough for him to request (unsuccessfully) that the umpire turn off the Hawk-Eye technology for the remainder of the match.[15]

In the 2009 Australian Open fourth round match between Roger Federer and Tomáš Berdych, Berdych challenged an out call. The Hawk-Eye system was not available when he challenged, likely due to a particularly pronounced shadow on the court. As a result, the original call stood.[16]

In the 2009 Indian Wells Masters quarterfinals match between Ivan Ljubičić and Andy Murray, Murray challenged an out call. The Hawk-Eye system indicated that the ball landed on the center of the line despite instant replay images showing that the ball was clearly out. It was later revealed that the Hawk-Eye system had mistakenly picked up the second bounce, which was on the line, instead of the first bounce of the ball.[17] Immediately after the match, Murray apologised to Ljubicic for the call, and acknowledged that the point was out.

The Hawk-Eye system was developed as a replay system, originally for TV broadcast coverage. As such, it initially could not call ins and outs live.

The Hawk-Eye Innovations website[18] states that the system performs with an average error of 3.6 mm. The standard diameter of a tennis ball is 67 mm, equating to a 5% error relative to ball diameter. This is roughly equivalent to the fluff on the ball.

Hawk-Eye is currently developing a technology called 'Hawk-Eye Live', which will use the 10 cameras to call shots in or out in real time, with an 'out' call being signified by a speaker emitting an 'out' sound that emulates a human line judge. The technology is currently in trials and is expected to be in place for the 2019 US Open.

Currently, only clay court tournaments, notably the French Open being the only Grand Slam, are found to be generally free of Hawk-Eye technology due to marks left on the clay where the ball bounced to evidence a disputed line call. Chair umpires are then required to get out of their seat and examine the mark on court with the player by his side to discuss the chair umpire's decision.

Unification of rules

Until March 2008, the International Tennis Federation (ITF), Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), Women's Tennis Association (WTA), Grand Slam Committee, and several individual tournaments had conflicting rules on how Hawk-Eye was to be utilised. A key example of this was the number of challenges a player was permitted per set, which varied among events.[19] Some tournaments allowed players a greater margin for error, with players allowed an unlimited numbers of challenges over the course of a match.[19] In other tournaments players received two or three per set.[19] On 19 March 2008, the aforementioned organizing bodies announced a uniform system of rules: three unsuccessful challenges per set, with an additional challenge if the set reaches a tiebreak. In an advantage set (a set with no tiebreak) players are allowed three unsuccessful challenges every 12 games. The next scheduled event on the men and women's tour, the 2008 Sony Ericsson Open, was the first event to implement these new, standardized rules.[20]

Association football

Hawk-Eye is one of the goal-line technology (GLT) systems authorised by FIFA. Hawk-Eye tracks the ball, and informs the referee if a ball fully crosses the goal line into the goal. The purpose of the system is to eliminate errors in assessing if a goal was scored. The Hawk-Eye system was one of the systems trialed by the sport's governors prior to the 2012 change to the Laws of the Game that made GLT a permanent part of the game,[21] and it has been used in various competitions since then. GLT is not compulsory and, owing to the cost of Hawk-Eye and its competitors, systems are only deployed in a few high-level competitions.

As of July 2017, licensed Hawk-Eye systems were installed at 96 stadiums. By number of installations, Hawk-Eye is the most popular GLT system.[22] Hawk-Eye is the system used in the Premier League,[23] and Bundesliga[24] among other leagues.

Snooker

At the 2007 World Snooker Championship, the BBC used Hawk-Eye for the first time in its television coverage to show player views, particularly of potential snookers.[25] It has also been used to demonstrate intended shots by players when the actual shot has gone awry. It is now used by the BBC at every World Championship, as well as some other major tournaments. The BBC used to use the system sporadically, for instance in the 2009 Masters at Wembley the Hawk-Eye was at most used once or twice per frame. Its usage has decreased significantly and is now only used within the World Championships and very rarely in any other tournament on the snooker tour. In contrast to tennis, Hawk-Eye is never used in snooker to assist referees' decisions and primarily used to assist viewers in showing what the player is facing.

Gaelic games

In Ireland, Hawk-Eye was introduced for all Championship matches at Croke Park in Dublin in 2013. This followed consideration by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) for its use in Gaelic football and hurling. A trial took place in Croke Park on 2 April 2011. The double-header featured football between Dublin and Down and hurling between Dublin and Kilkenny. Over the previous two seasons there had been many calls for the technology to be adopted, especially from Kildare fans, who saw two high-profile decisions go against their team in important games. The GAA said it would review the issue after the 2013 Sam Maguire Cup was presented.[26]

Hawk-Eye's use was intended to eliminate contentious scores.[27] It was first used in the Championship on Saturday 1 June 2013 for the Kildare versus Offaly game, part of a double header with a second game of Dublin versus Westmeath.[28] It was used to confirm that Offaly substitute Peter Cunningham's attempted point had gone wide 10 minutes into the second half.[29]

Use of Hawk-Eye was suspended during the 2013 All-Ireland hurling semi-finals on 18 August due to a human error during an Under-18 hurling game between Limerick and Galway.[30] During the minor game, Hawk-Eye ruled a point for Limerick as a miss although the graphic showed the ball passing inside the posts, causing confusion around the stadium – the referee ultimately waved the valid point wide provoking anger from fans, viewers and TV analysts covering the game live.[31] The system was subsequently stood down for the senior game which followed, owing to "an inconsistency in the generation of a graphic".[32] Limerick, who were narrowly defeated after extra-time, announced they would be appealing over Hawk-Eye's costly failure.[30] Hawk-Eye apologised for this incident and admitted that it was a result of human error. There have been no further incidents during the GAA. The incident drew attention from the UK, where Hawk-Eye had made its debut in English football's Premier League the day before.[33]

Hawk-Eye was introduced to a second venue, Semple Stadium, Thurles, in 2016. There is no TV screen at Semple: instead, an electronic screen displays a green Tá if a score has been made, and a red Níl if the shot is wide.[34]

It was used at a third venue, Páirc Uí Chaoimh, Cork, in July 2017, for the All-Ireland hurling quarter finals between Clare versus Tipperary and Wexford versus Waterford.[35]

No official Irish-language term exists, although some publications have used the direct translation Súil an tSeabhaic.[36][37][38]

Australian football

On 4 July 2013, the Australian Football League announced that they would be testing Hawk Eye technology to be used in the Score Review process. Hawk Eye was used for all matches played at the MCG during Round 15 of the 2013 AFL Season. The AFL also announced that Hawk Eye was only being tested, and would not be used in any Score Reviews during the round.

Badminton

BWF introduced Hawk-Eye technology in 2014 after testing other instant review technologies for line call decision in BWF major events.[39] Hawk-Eye's tracking cameras are also used to provide shuttlecock speed and other insight in badminton matches.[40] Hawk-Eye was formally introduced in 2014 India Super Series tournament.

Doubts

Hawk-Eye is now familiar to sport fans around the world for the views it brings into sports like cricket and tennis. Although this new technology has for the most part been embraced, it has received criticism from some quarters. In the 2007 Wimbledon Championships a shot that appeared to be out, was called by Hawk-Eye as in by 1 mm, a distance smaller than the advertised margin of error of 3.6 mm.[41] Some commentators have criticised the system's 3.6 mm statistical margin of error as too large.[42] Others have noted that while 3.6 mm is extraordinarily accurate, this margin of error is only for the witnessed trajectory of the ball. In 2008, an article in a peer-reviewed journal[43] consolidated many of these doubts. The authors acknowledged the value of the system, but noted that it was probably fallible to some extent, and that its failure to depict a margin of error gave a spurious depiction of events. The authors also argued that the probable limits to its accuracy were not acknowledged by players, officials, commentators or spectators. They hypothesised that Hawk-Eye may struggle with predicting the trajectory of a cricket ball after bouncing: the time between a ball bouncing and striking the batsman may be too short to generate the three frames (at least) needed to plot a curve accurately.

Use in computer games

The use of the Hawk-Eye brand and simulation has been licensed to Codemasters for use in the video game Brian Lara International Cricket 2005 to make the game appear more like television coverage, and subsequently in Brian Lara International Cricket 2007, Ashes Cricket 2009 and International Cricket 2010. A similar version of the system has since been incorporated into the Xbox 360 version of Smash Court Tennis 3, but it is not present in the PSP version of the game, although it does feature a normal challenge of the ball which does not use the Hawk-Eye feature. It is also featured (Called Big Eye) in Don Bradman Cricket 2014 and 2017.

See also

References

- Two British scientists call into question Hawk-Eye's accuracy – Tennis – ESPN. Sports.espn.go.com (19 June 2008). Retrieved on 15 August 2010.

- "Hawkeye and Shot Spot Technology on All Surfaces: The Red Clay Controversy". bleacherreport.com. 7 June 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- "Hawk-Eye at Wimbledon: it's not as infallible as you think". The Guardian. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Gibson, Owen (11 April 2013). "Premier League clubs choose Hawk-Eye to provide new goalline technology". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- "Bundesliga approves Hawk-Eye goal-line technology for new season". The Observer. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- VIDEO PROCESSOR SYSTEMS FOR BALL TRACKING IN BALL GAMES esp@cenet Patent document, 14 June 2001

- "Hawk-Eye ball-tracking firm bought by Sony". BBC News. 7 March 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- Website company: About Hawk Eye Archived 9 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, visited 25 May 2012

- "About ICC – Rules and Regulations". Icc-cricket.yahoo.com. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "Nine admits Hawk-Eye not foolproof » The Roar – Your Sports Opinion". The Roar. 24 January 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Can Cameras and Software Replace Referees?" Popular Mechanics. (12 May 2010). Retrieved on 3 September 2010.

- Archived 21 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Barry Wood (2 March 2007). "Tennis: Nadal blames line calling system for losing – 02 Mar 2007 – nzherald: Sports news – New Zealand and International Sport news and results". nzherald. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "Gulfnews: Hawk-Eye leaves Nadal and Federer at wits' end". Archive.gulfnews.com. 3 March 2007. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Pavia, Will (10 July 2007). "Hawk-Eye creator defends his system after Federers volley". The Times. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "Berdych joins Federer in anti-Hawk-Eye club". 27 January 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- "When computers get it wrong". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 24 March 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "Home :: Hawk-Eye". Hawkeyeinnovations.co.uk. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- Newman, Paul (23 June 2007). "Hawk-Eye makes history thanks to rare British success story at Wimbledon". The Independent. London. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- "Hawk-Eye challenge rules unified". BBC News. 19 March 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- Conway, Richard (15 April 2012). "Goal-line technology edges closer". BBC Sport. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Football Technology - RESOURCE HUB". FIFA. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Goal-line technology: Premier League votes in favour for 2013-14". BBC. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- "Bundesliga approves Hawk-Eye goal-line technology for new season".

- "Press Office – BBC Sport to feature Hawk-eye in World Snooker Championship coverage". BBC. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "GAA to trial Hawk-Eye at Croke Park". The Irish Times. 24 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Uses in Gaelic football and hurling.

- "GAA hopes Hawk-Eye will eliminate contentious points". RTÉ Sport. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "Live: Saturday's GAA Championship action". RTÉ Sport. 1 June 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

18:41 - A quick observation on Hawkeye which was used for the first time in the Kildare v Offaly game. It did not delay the game at all and the result came through on our screens within 15 seconds of the referee calling for Hawkeye. The composite picture on television showed clearly that the ball had gone wide. Good start for the new technology.

- "Hawkeye makes successful debut". Hogan Stand. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- "Hawk-Eye admits to human error at Croke Park as Limerick confirm appeal". RTÉ Sport. 19 August 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "GAA's 'Hawkeye' stood down following error during All-Ireland minor semi-final". Irish Independent. 18 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Limerick to appeal after Hawk-Eye blunder in minor hurling game". BBC Sport. 20 August 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- "Irish officials suspend Hawk-Eye system after glitch". Reuters. 19 August 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "Semple Stadium to use HawkEye for Cork clash".

- "Hawk-Eye will be used at Páirc Uí Chaoimh". RTÉ.

- "A bhfuil romhainn amach ar an ngarraí glas agus lasmuigh de as seo go ceann bliana…".

- "Colun: Cartai Cuil:". 29 September 2014.

- "Contae an Chláir i lár an aonaigh in athuair?".

- Alleyne, Gayle. "'Hawk-Eye' to Determine 'In or Out'". bwfbadminton.org. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- "Hawk-Eye in Badminton". hawkeyeinnovations.co.uk. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- IEEE Spectrum: Hawk-Eye in the Crosshairs at Wimbledon Again. Spectrum.ieee.org. Retrieved on 15 August 2010.

- Big debate: Was Roger Federer right to criticise Hawk-Eye? | Sport. The Guardian. Retrieved on 15 August 2010.

- Collins, H. and Evans, R. 2008. "You Cannot Be Serious! Public understanding of technology with special reference to 'Hawk-Eye'". Public Understanding of Science 17:3, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)