New Woman

The New Woman was a feminist ideal that emerged in the late 19th century and had a profound influence on feminism well into the 20th century. In 1894, Irish writer Sarah Grand used the term "new woman" in an influential article, to refer to independent women seeking radical change, and in response the English writer 'Ouida' (Maria Louisa Rame) used the term as the title of a follow-up article.[1][2] The term was further popularized by British-American writer Henry James, who used it to describe the growth in the number of feminist, educated, independent career women in Europe and the United States.[3] Independence was not simply a matter of the mind: it also involved physical changes in activity and dress, as activities such as bicycling expanded women's ability to engage with a broader more active world.[4]

%2C_1896.jpg)

The New Woman pushed the limits set by a male-dominated society, especially as modeled in the plays of Norwegian Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906).

Changing social roles

Writer Henry James was among the authors who popularized the term "New Woman", a figure who was represented in the heroines of his novels—among them the title character of the novella Daisy Miller (serialized 1878), and Isabel Archer in Portrait of a Lady (serialized 1880–81). According to historian Ruth Bordin, the term New Woman was

intended by [James] to characterize American expatriates living in Europe: women of affluence and sensitivity, who despite or perhaps because of their wealth exhibited an independent spirit and were accustomed to acting on their own. The term New Woman always referred to women who exercised control over their own lives be it personal, social, or economic.[5]

The "New Woman" was also a nickname given to Ella Hepworth Dixon, the English author of the novel The Story of a Modern Woman.[6]

Postsecondary and professional education

Although the New Woman was becoming a more active participant in life as a member of society and the workforce, she was most often depicted exerting her autonomy in the domestic and private spheres in literature, theatre, and other artistic representations.[5] The 19th-century suffragette movement to gain women's democratic rights was the most significant influence on the New Woman. Education and employment opportunities for women were increasing as western countries became more urban and industrialized. The "pink-collar" workforce gave women a foothold in the business and institutional sphere. In 1870, women in the professions comprised only 6.4 percent of the United States' non-agricultural workforce; by 1910, that figure had risen to 10 percent, then to 13.3 percent in 1920.[7]

More women were winning the right to attend university or college. Some were obtaining a professional education and becoming lawyers, doctors, journalists, and professors, often at prestigious all-female colleges such as the Seven Sisters schools: Barnard, Bryn Mawr, Mount Holyoke, Radcliffe, Smith, Vassar, and Wellesley. The New Woman in the United States was participating in post-secondary education in larger numbers by the turn of the 20th century. Alice Freeman Palmer became Wellesley's first woman president in 1881, while Mount Holyoke had elected female leadership since its founding in 1837.

Sexuality and social expectations

Autonomy was a radical goal for women at the end of the 19th century. It was historically a truism that women were always legally and economically dependent on their husband, male relatives, or social and charitable institutions. The emergence of education and career opportunities for women in the late 19th century, as well as new legal rights to property (although not yet the vote), meant that they stepped into a new position of freedom and choice when it came to marital and sexual partners. The New Woman placed great importance on her sexual autonomy, but that was difficult to put into practice as society still voiced loud disapproval of any sign of female licentiousness. For women in the Victorian era, any sexual activity outside of marriage was judged to be immoral. Divorce law changes during the late 19th century gave rise to a New Woman who could survive a divorce with her economic independence intact, and an increasing number of divorced women remarried. Maintaining social respectability while exercising legal rights still judged to be immoral by many was a challenge for the New Woman:

Mary Heaton Vorse put her compromise this way: "I am trying for nothing so hard in my own personal life as how not to be respectable when married."[7]

It was clear in the novels of Henry James that however free his heroines felt to exercise their intellectual and sexual autonomy, they ultimately paid a price for their choices.

Some admirers of the New Woman trend found freedom to engage in lesbian relationships through their networking in women's groups. It has been said that for some of them, "loving other women became a way to escape what they saw as the probabilities of male domination inherent in a heterosexual relationship".[7] For others, it may have been the case that economic independence meant that they were not answerable to a guardian for their sexual or other relationship choices, and they exercised that new freedom.

Class differences

The New Woman was a result of the growing respectability of postsecondary education and employment for women who belonged to the privileged upper classes of society. University education itself was still a badge of affluence for men at the turn of the 20th century, and fewer than 10 percent of people in the United States had a postsecondary education during the era.

The women entering universities generally belonged to the white middle class. Consequentially, the working class, people of color, and immigrants were often left behind in the race to achieve this new feminist model. Woman writers belonging to these marginalized communities often critiqued the way in which their newfound freedom regarding their gender came at the expense of their race, ethnicity, or class. Although they acknowledged and respected the independence of the New Woman, they could not ignore the issue that the standards for a New Woman of the Progressive Era could, for the most part, only be attained by white middle-class women.[8]

Literature

Literary discussions of the expanding potential for women in English society date back at least to Maria Edgeworth's Belinda (1801) and Elizabeth Barrett's Aurora Leigh (1856), which explored a woman's plight between conventional marriage and the radical possibility that a woman could become an independent artist. In drama, the late nineteenth century saw such "New Woman" plays as Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House (1879) and Hedda Gabler (1890), Henry Arthur Jones's play The Case of Rebellious Susan (1894) and George Bernard Shaw's controversial Mrs. Warren's Profession (1893) and Candida (1898). According to a joke by Max Beerbohm (1872–1956), "The New Woman sprang fully armed from Ibsen's brain"[9] (an allusion to the birth of Athena).

Bram Stoker's Dracula makes prominent mention of the New Woman in its pages, with its two main female characters discussing the changing roles of women and the New Woman in particular. Mina Harker goes on to embody several characteristics of the New Woman, employing skills such as typing and deductive reasoning, to the amusement of the older male characters. Lucy Westrenra wonders if the New Woman could marry several men at once, which shocks her friend, Mina. Feminist analyses of Dracula regard male anxiety about the Woman Question and female sexuality as central to the book.[10]

The term was used by writer Charles Reade in his novel A Woman Hater, originally published serially in Blackwood's Magazine and in three volumes in 1877. Of particular interest in the context are Chapters XIV and XV in volume two, which made the case for the equal treatment of women and arguably sparked off the whole Women's Movement in the latter part of the 19th century.[11]

In fiction, New Woman writers included Olive Schreiner, Annie Sophie Cory (Victoria Cross), Sarah Grand, Mona Caird, George Egerton, Ella D'Arcy and Ella Hepworth Dixon. Some examples of New Woman literature are Victoria Cross's Anna Lombard (1901), Dixon's The Story of a Modern Woman and H. G. Wells's Ann Veronica (1909).

Kate Chopin's The Awakening (1899) also deserves mention, especially within the context of narratives derived from Flaubert's Madame Bovary (1856), both of which chronicle a woman's doomed search for independence and self-realization through sexual experimentation.

The emergence of the fashion-oriented and party-going flapper in the 1920s marks the end of the New Woman era (now also known as First-wave feminism).

Art

Women artists became part of professional enterprises, including founding their own art associations. Artwork made by women was considered to be inferior, and to help overcome that stereotype women became "increasingly vocal and confident" in promoting women's work, and thus became part of the emerging image of the educated, modern and freer "New Woman".[12]

In the late 19th century Charles Dana Gibson depicted the "New Woman" in his painting, The Reason Dinner was Late, which is "a sympathetic portrayal of artistic aspiration on the part of young women" as she paints a visiting policeman.[13][14]

Artists "played crucial roles in representing the New Woman, both by drawing images of the icon and exemplyfying this emerging type through their own lives". In the late 19th and early 20th centuries about 88% of the subscribers of 11,000 magazines and periodicals were women. As women entered the artist community, publishers hired women to create illustrations that depicted the world through a woman's perspective. Successful illustrators included Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, Jessie Wilcox Smith, Rose O'Neill, Elizabeth Shippen Green, and Violet Oakley.[15]

"Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition"[16]

During the 19th century there were a significant number of women who became successful, educated artists, a rarity before that time, with the exception of a few like Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) and Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842).[17] The emerging women artists created works with a different perspective than men who represented the feminine in floral depictions of passivity, ornamentality and sexual purity; challenged the limited concepts of femininity; and created a genre of floral-female paintings in which "the artist placed one woman or more in a flower garden setting and manipulated composition, color, texture and form to make the women look as much like flowers as possible" but with a different viewpoint of what feminine meant. The approach was not used for portraits. Its form of feminine representation has largely gone unrecognized by American art scholars and conservative society, ignored in response to the burgeoning "New Woman" beginning in the late 19th century.[18] Anna Lea Merritt (1844–1930) created flower-feminine paintings; noting floral-feminine symbolism employed by male artists like Charles Courtney Curran and Robert Reid, Merritt said that she saw "flowers as 'great ladies' noting that 'theirs is the langour of high breeding, and the repose and calm of weary idleness".[19] Emma Lampert Cooper (1855–1920) was one of the well-educated artists who became a successful landscape painter and academic figure after having begun as a children's book illustrator and painter of miniatures and flower paintings. Realizing the difficulty in making the transition to a successful painter, particularly of landscape and figure paintings, Cooper warned other women artists of the difficulty in creating a successful career in such works, but was able to do so herself after becoming a success in Rochester, New York and studying in Europe.[17]

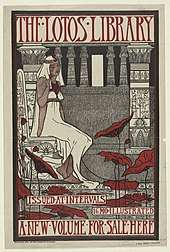

Violet Oakley, lithograph for The Lotos Library (1896)

Violet Oakley, lithograph for The Lotos Library (1896) Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth, 1914, Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts

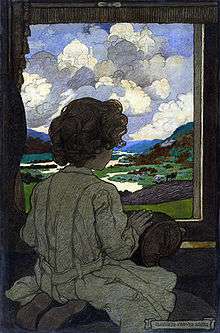

Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth, 1914, Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts Elizabeth Shippen Green, The Journey, illustration for Josephine Preston Peabody's "The Little Past", which relates experiences of childhood from a child's perspective.

Elizabeth Shippen Green, The Journey, illustration for Josephine Preston Peabody's "The Little Past", which relates experiences of childhood from a child's perspective. Elizabeth Shippen Green, Life was made for love and cheer, illustration depicting Green, Jessie Willcox Smith, Violet Oakley and other friends.

Elizabeth Shippen Green, Life was made for love and cheer, illustration depicting Green, Jessie Willcox Smith, Violet Oakley and other friends. Rose O'Neill, "Signs", a cartoon for Puck, 1904.

Rose O'Neill, "Signs", a cartoon for Puck, 1904.

Ethel: "He acts this way. He gazes at me tenderly, is buoyant when I am near him, pines when I neglect him. Now, what does that signify?"

Her mother: "That he's a mighty good actor, Ethel." Jessie Wilcox Smith, cover of Heidi, 1922

Jessie Wilcox Smith, cover of Heidi, 1922

Commentary

The new woman, in the sense of the best woman, the flower of all the womanhood of past ages, has come to stay — if civilization is to endure. The sufferings of the past have but strengthened her, maternity has deepened her, education is broadening her — and she now knows that she must perfect herself if she would perfect the race, and leave her imprint upon immortality, through her offspring or her works.

— Winnifred Harper Cooley: The New Womanhood (New York, 1904) 31f.

I hate that phrase "New Woman." Of all the tawdry, run-to-heel phrases that strikes me the most disagreeably. When you mean, by the term, the women who believe in and ask for the right to advance in education, the arts, and professions with their fellow-men, you are speaking of a phase in civilisation which has come gradually and naturally, and is here to stay. There is nothing new or abnormal in such a woman. But when you confound her with the extremists who wantonly disown the obligations and offices with which nature has honored them, you do the earnest, progressive women great wrong.

— Emma Wolf, The Joy of Life (1896).

Opposition

In the early 1890s, daughters of middle class Catholics expressed a desire to attend institution of higher education. Catholic leaders expressed their concern as studying at these "Protestant" schools, as the Church described it, might threaten the women's Catholic faith.[20] The Church also viewed the New Woman as a threat to traditional womanhood and the social order.[21] The Church cited past accomplished Catholic women, including saints, to critique the New Woman. By citing those women, the Church also argued that it was the Church, not the New Woman movement, that offered women the best opportunities.[20] Others also critiqued the New Woman for her implied sexual freedom and for her desire to participate in matters that are best left to men's judgment.[22] As Cummings writes, the New Woman was accused of being "essentially uncatholic and anti-catholic".[22]

Other countries

China

Literary figures from western texts, like Henrik Ibsen's Doll House (1879), became examples of New Women and female revolutionary figures well known to Chinese urban intellectuals at the time. These figures were highly educated and self-absorbed. Nora, the heroine of Doll House, leaves her patriarchal marriage. An important lecture, "What Happens After Nora Leaves Home", was given at Beijing Women's Normal College in 1923.[23]

The emergence of the New Culture movement in the early 1900s in China condemned “slavish Confucian tradition” which sacrificed the individual to conformity and rigid notions of subservience, loyalty, and female chastity.[24]

Unable to follow the constructs of patriarchal culture, some new women resorted to suicide. According to Margery Wolf, "if a virtuous act of self-destruction could reveal the moral agency of the suicide, then suicide could also provide evidence of external, criminal agency." She postulated further that suicide was the most powerful accusation that a woman could make. The social and legal response was not so much “Why?” (a question of individual psychology) but, rather, “Who drove her to this?” (a question of social responsibility)".[25][26]

Germany

After women gained the right to vote and be elected in the wake of World War I in Germany, the Neue Frau became a trope in German popular culture, representing new discourses about sexuality, reproduction and urban mass society. This German New Woman was portrayed by authors such as Elsa Herrmann (So ist die neue Frau, 1929) and Irmgard Keun (Das kunstseidene Mädchen, 1932, translated as The Artificial Silk Girl, 1933). These urbane, sexually liberated working women wore androgynous clothes, cut their hair short, and were widely seen as apolitical.[27]

Korea

In Korea in the 1920s, the New Woman's Movement arose among educated Korean women who protested the Confucian patriarchal tradition. During a period of Japanese imperialism, Christianity was seen as an impetus for Korean nationalism and had been involved in events such as the March 1st Movement of 1919 for independence. Hence, in contrast to many Western contexts, Christianity informed the ideals of Western feminism and women's education, especially through the Ewha Womans University.[28] The New Woman's Movement is often seen to be connected with the Korean magazine New Women (Korean: 신여자; Hanja: 新女者; MR: Sin yŏja), founded in 1920 by Kim Iryŏp, which included other key figures such as Na Hye-sŏk.[29]

Japan

"Atarashii onna" was used with derision by critics to denote a woman who was promiscuous, shallow, and unfilial, [30] the opposite of Meiji Japan's ideals of ryōsai kenbo. Despite this, members of Seitō, such as Hiratsuka Raichō and Itō Noe proudly embraced the term. Hiratsuka Raichō, founder and editor of Seitō had this to say about being a new woman: "I am a new woman. As new women, we have always insisted that women are also human beings. It is common knowledge that we have opposed the existing morality, and have maintained that women have the right to express themselves as individuals and to be respected as individuals." [31] In her essay, "The Path of the New Woman," published in Seitō in the January 1913 issue, Itō Noe proclaimed her commitment to pursuing the path of a New Woman and urged others to do the same despite societal backlash. "How could anyone imagine that the way of the New Woman, the way of this pioneer, be anything less than one continuous, torturous struggle?" [30]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: New Woman |

References

- See Sally Ledger, 'The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siecle', Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.

- "Daughters of decadence: the New Woman in the Victorian fin de siècle". The British Library. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Stevens, Hugh (2008). Henry James and Sexuality. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780521089852.

- Roberts, Jacob (2017). "Women's work". Distillations. 3 (1): 6–11. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Bordin, Ruth Birgitta Anderson (1993). Alice Freeman Palmer: The Evolution of a New Woman. University of Michigan Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780472103928.

- ODNB entry for Ella Hepworth Dixon, by Nicola Beauman. Retrieved 25 July 2013. Pay-walled.; London: W. Heinemann, 1894. The Story of a Modern Woman, ed. Steve Farmer (Toronto: Broadview Literary Texts, 2004). ISBN 1551113805.

- Lavender, Catherine. "Notes on The New Woman" (PDF). The College of Staten Island/CUNY. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Rich, Charlotte (2009). Transcending the New Woman: Multiethnic Narratives in the Progressive Era. Colombia, United States: University of Missouri Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8262-6663-7.

- "The New Woman"

- Bjørklund, Miriam. ""To face it like a man": Exploring Male Anxiety in Dracula and the Sherlock Holmes Canon" (PDF). Thesis, University of Oslo. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- A Woman Hater Vol. II, pp.[1] - 74, and p.149

- Laura R. Prieto. At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America. Harvard University Press; 2001. ISBN 978-0-674-00486-3. pp. 145–146.

- Nancy Mowall Mathews. "The Greatest Woman Painter": Cecilia Beaux, Mary Cassatt, and Issues of Female Fame. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- The Gibson Girl as the New Woman. Library of Congress. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- Laura R. Prieto. At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America. Harvard University Press; 2001. ISBN 978-0-674-00486-3. p. 160–161.

- Annette Stott. "Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition". American Art. The University of Chicago Press. 6: 2 (Spring, 1992). p. 61.

- Annette Stott. "Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition". American Art. The University of Chicago Press. 6: 2 (Spring, 1992). p. 75.

- Annette Stott. "Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition". American Art. The University of Chicago Press. 6: 2 (Spring, 1992). pp. 61–67.

- Annette Stott. "Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition". American Art. The University of Chicago Press. 6: 2 (Spring, 1992). p. 62.

- Cummings, Kathleen Sprows (2009-02-15). New Women of the Old Faith. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 8. doi:10.5149/9780807889848_cummings. ISBN 9780807832493.

- Cummings, Kathleen Sprows (2009-02-15). New Women of the Old Faith. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 6. doi:10.5149/9780807889848_cummings. ISBN 9780807832493.

- Cummings, Kathleen Sprows (2009-02-15). New Women of the Old Faith. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 19. doi:10.5149/9780807889848_cummings. ISBN 9780807832493.

- Molony, Barbara, Janet M. Theiss, and Hyaeweol Choi. Gender in Modern East Asia First Edition. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2016.

- Goodman, Bryna (2005). "The New Woman Commits Suicide: The Press, Cultural Memory and the New Republic". The Journal of Asian Studies. 64 (1): 67–101. doi:10.1017/S0021911805000069. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 25075677.

- Wolf, Margery (1975). Women and Suicide in China. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan: Women in China: Studies in Social Change and Feminism. p. 68.

- Molony, Barbara (2016-03-29). Gender in modern East Asia : an integrated history. Theiss, Janet M., 1964-, Choi, Hyaeweol (First ed.). Boulder, CO. ISBN 978-0-8133-4875-9. OCLC 947808181.

- Sneeringer, Julia (2002). Winning Women's Votes: Propaganda and Politics in Weimar Germany. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 125, 152, 161, 199, 278.

- Kwon, Insook (November 1998). "'The New Women's Movement' in 1920s Korea: Rethinking the Relationship Between Imperialism and Women". Gender & History. 10 (3): 381–405. doi:10.1111/1468-0424.00110. ISSN 1468-0424.

- Choi, Hyaeweol (2012). New Women in Colonial Korea: A Sourcebook. Routledge. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-415-51709-6.

- Bardsley, Jan. The bluestockings of Japan : new woman essays and fiction from Seitō, 1911-16. Ann Arbor. ISBN 9781929280445. OCLC 172521673.

- Sato, Barbara (2003). The New Japanese Woman. doi:10.1215/9780822384762. ISBN 978-0-8223-3008-0.

Sources

- A New Woman Reader, ed. Carolyn Christensen Nelson (Broadview Press: 2000) (ISBN 1-55111-295-7) (contains the text of Sydney Grundy's 1894 satirical comedy actually entitled The New Woman)

- Martha H. Patterson: Beyond the Gibson Girl: Reimagining the American New Woman, 1895–1915 (University of Illinois Press: 2005) (ISBN 0-252-03017-6)

- Sheila Rowbotham: A Century of Women. The History of Women in Britain and the United States (Penguin Books: 1999) (ISBN 0-14-027902-4), Chapters 1–3.

- Patterson, Martha H. The American New Woman Revisited (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008) (ISBN 0813542960)