Khanda (sword)

The khanda is a double-edge straight sword originating from the Indian subcontinent. It is often featured in religious iconography, theatre and art depicting the ancient history of India. It is a common weapon in Indian martial arts.[1] Khanda often appears in Hindu, Jain, Buddhist and Sikh scriptures and art.[2]

| Khanda | |

|---|---|

A khanda | |

| Type | Sword |

| Place of origin | Indian subcontinent |

| Production history | |

| Produced | Similar weapons used from at least the Gupta period (320-550 CE) to present. |

| Specifications | |

| Blade type | Double-edged, straight bladed, blunt tipped |

Etymology

The word khanda has its origins in the Sanskrit khaḍga[3] (खड्ग) or khaṅga, from a root khaṇḍ meaning "to break, divide, cut, destroy". The older word for a bladed weapon, asi, is used in the Rigveda in reference to either an early form of the sword or to a sacrificial knife or dagger to be used in war.

Appearance

The blade broadens from the hilt to the point, which is usually quite blunt. While both edges are sharp, one side usually has a strengthening plate along most of its length, which both adds weight to downward cuts and allows the wielder to place their hand on the plated edge. The hilt has a large plate guard and a wide finger guard connected to the pommel. The pommel is round and flat with a spike projecting from its centre. The spike may be used offensively or as a grip when delivering a two-handed stroke. The hilt is identical to that employed on another South Asian straight sword, the firangi.

History

Early swords appear in the archaeological record of ritual copper swords in Fatehgarh Northern India and Kallur in Southern India.[4] although the Puranas and Vedas give an even older date to the sacrificial knife.[5] Straight swords, (as well as other swords curved both inward and outward), have been used in Indian history since the Iron Age Mahajanapadas (roughly 600 to 300 BC), being mentioned in the Sanskrit epics, and used in soldiers in armies such as those of the Mauryan Empire. Several sculptures from the Gupta era (AD 280-550) portray soldiers holding khanda-like broadswords. These are again flared out at the tip. They continued to be used in art such as Chola-era murtis.

There is host of paintings depicting the khanda being worn by Rajput kings throughout the medieval era. It was used usually by foot-soldiers and by nobles who were unhorsed in battle. The Rajput warrior clans venerated the khanda as a weapon of great prestige.

According to some, the design was improved by Prithviraj Chauhan. He added a back spine on the blade to add more strength. He also made the blade wider and flatter, making it a formidable cutting weapon. It also gave a good advantage to infantry over light cavalry enemy armies.

Rajput warriors in battle wielded the khanda with both hands and swung it over their head when surrounded and outnumbered by the enemy. It was in this manner that they traditionally committed an honourable last stand rather than be captured. Even today they venerate the khanda on the occasion of Dasara.

Maharana Pratap is known to have wielded a khanda. The son in law of Miyan Tansen Naubat Khan also wielded khanda and the family was known as Khandara Beenkar. Wazir Khan Khandara was a famous beenkar of 19th century.

Many Sikh warriors of the Akali-Nihang order are known to have wielded khandas. For instance, Akali Deep Singh is famous for wielding a khanda in his final battle before reaching his death, which is still preserved at Akaal Takhat Sahib.[6] Akali Phula Singh is also known to have wielded a khanda, and this practise was popular among officers and leaders in the Sikh Khalsa Army as well as by Sikh sardars of the Misls and of the Sikh Empire. The Sikh martial art, Gatka also uses khandas.

In Religion

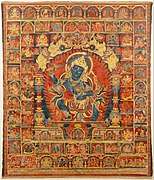

In Dharmic religions, Khanda is represented as wisdom cutting through veil of ignorance. Hindu and Buddhist deities are often shown wielding or holding khanda sword in religious art. Notably, Buddhist guardian deities like Arya Achala, Manjushri, Mahakala, Palden Lhamo etc.

Gallery

- Manjushri wielding Khanda.

Acala wielding Khanda.

Acala wielding Khanda.- Mahakala wielding Khanda.

- Acala holding Khanda in up-right position.

See also

References

- M. L. K. Murty (2003), p91

- Teece, Geoff. Sikhism. Black Rabbit Books. p. 18. ISBN 1583404694.

- Rocky Pendergrass, 2015,Mythological Swords, Page 10.

- Murty, M. L. K. (2003) [2003]. Pre- and Protohistoric Andhra Pradesh Up to 500 B.C. Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-2475-1.

- Allchin, F. R. (1979) [1979]. "A South Indian Copper Sword and its significance". In Johanna Engelberta, Lohuizen-De Leeuw (ed.). South Asian Archaeology 1975: Papers from the Third International. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-05996-2.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-06-02. Retrieved 2015-07-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The History and Culture of the Indian People - Bharatiya Vidya Bhawan

- Hindu Arms and Ritual - Robert Elgood

- When the Body Becomes All Eyes: Paradigms, Discourses and Practices of Power in Kalarippayattu, a South Indian Martial Art - Phillip B. Zarrilli

- The Art of War in Ancient India - P.C. Chakravarti