Kannada

Kannada (/ˈkɑːnədə, ˈkæn-/;[7][8] ಕನ್ನಡ [ˈkɐnnɐɖaː]; less commonly known as Kanarese)[9][10] is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka in south western region of India. The language is also spoken by linguistic minorities in the states of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Kerala and Goa; and also by Karnatakas expats abroad. The language has roughly 43 million native speakers by 2011,[11] who are called Kannadigas. Kannada is also spoken as a second and third language by over 12.9 million non-Kannada speakers in Karnataka, which adds up to 56.9 million speakers.[12] It is one of the scheduled languages of India and the official and administrative language of the state of Karnataka.[13] Kannada was the court language of some of the most powerful empires of South and Central India, such as the Chalukya dynasty, the Rashtrakuta dynasty, the Vijayanagara Empire and the Hoysala Empire.

| Kannada | |

|---|---|

| ಕನ್ನಡ | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [ˈkɐnnɐɖaː] |

| Native to | India |

| Region | Karnataka with border communities in neighbouring states. Place of Origin Bidar & parts of North Karnataka. |

| Ethnicity | Kannadiga |

Native speakers | 52 million Native speakers by 2021(projection) (2021)[1][2] L2 speakers: 13 million[1] |

Dravidian

| |

Early form | |

| Kannada script Kannada Braille Tigalari script (formerly) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Various academies and the government of Karnataka[4] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | kn |

| ISO 639-2 | kan |

| ISO 639-3 | kan |

| Glottolog | nucl1305[5] |

| Linguasphere | 49-EBA-a |

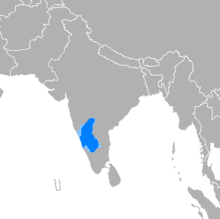

Distribution of Kannada native speakers, majority regions in dark blue and minority regions in light blue.[6] | |

The Kannada language is written using the Kannada script, which evolved from the 5th-century Kadamba script. Kannada is attested epigraphically for about one and a half millennia and literary Old Kannada flourished in the 6th-century Ganga dynasty[14] and during the 9th-century Rashtrakuta Dynasty.[15][16] Kannada has an unbroken literary history of over a thousand years.[17] Kannada literature has been presented with 8 Jnanapith awards, the most for any Dravidian language and the second highest for any Indian language.[18][19][20]

Based on the recommendations of the Committee of Linguistic Experts, appointed by the ministry of culture, the government of India designated Kannada a classical language of India.[21][22] In July 2011, a center for the study of classical Kannada was established as part of the Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysore to facilitate research related to the language.[23]

Development

Kannada is a Southern Dravidian language, and according to scholar Sanford B. Steever, its history can be conventionally divided into three periods: Old Kannada (Halegannada) from 450–1200 CE, Middle Kannada (Nadugannada) from 1200–1700, and Modern Kannada from 1700 to the present.[24] Kannada is influenced to an appreciable extent by Sanskrit. Influences of other languages such as Prakrit and Pali can also be found in the Kannada language. The scholar Iravatham Mahadevan indicated that Kannada was already a language of rich oral tradition earlier than the 3rd century BCE, and based on the native Kannada words found in Prakrit inscriptions of that period, Kannada must have been spoken by a widespread and stable population.[25][26] The scholar K. V. Narayana claims that many tribal languages which are now designated as Kannada dialects could be nearer to the earlier form of the language, with lesser influence from other languages.[25]

Sanskrit and Prakrit influence

The sources of influence on literary Kannada grammar appear to be three-fold: Pāṇini's grammar, non-Paninian schools of Sanskrit grammar, particularly Katantra and Sakatayana schools, and Prakrit grammar.[27] Literary Prakrit seems to have prevailed in Karnataka since ancient times. The vernacular Prakrit speaking people may have come into contact with Kannada speakers, thus influencing their language, even before Kannada was used for administrative or liturgical purposes. Kannada phonetics, morphology, vocabulary, grammar and syntax show significant influence from these languages.[27][28]

Some naturalised (tadbhava) words of Prakrit origin in Kannada are: baṇṇa (colour) derived from vaṇṇa, hunnime (full moon) from puṇṇivā. Examples of naturalized Sanskrit words in Kannada are: varṇa (colour), paurṇimā, and rāya from rāja (king).[29]

Like the other non Aryan languages Kannada also has borrowed (tatsama) words such as dina (day), kopa (anger), surya (sun), mukha (face), nimiṣa (minute) and anna (rice).[30]

History

Early traces

_at_the_Durga_Devi_temple_in_Virupaksha_temple_complex_at_Hampi.jpg)

.jpg)

_in_Kalleshvara_temple_at_Hire_Hadagali.jpg)

_of_King_Vikramaditya_VI_in_the_Mahadeva_temple_at_Itagi.jpg)

_at_Gaurishvara_temple_at_Yelandur_1.jpg)

Purava Hale Gannada: This Kannada term literally translated means "Previous form of Old Kannada" was the language of Banavasi in the early Common Era, the Satavahana, Chutu Satakarni (Naga) and Kadamba periods and thus has a history of over 2500 years.[26][31][32][33][34][35][36] The Ashoka rock edict found at Brahmagiri (dated to 230 BCE) has been suggested to contain words in identifiable Kannada.[37]

In some 3rd–1st century BCE Tamil inscriptions, words of Kannada influence such as nalliyooraa, kavuDi and posil have been introduced. The use of the vowel a as an adjective is not prevalent in Tamil but its usage is available in Kannada. Kannada words such as gouDi-gavuDi transform into Tamil's kavuDi for lack of the usage of Ghosha svana in Tamil. Hence the Kannada word 'gavuDi' becomes 'kavuDi' in Tamil. 'Posil' ('hosilu') was introduced into Tamil from Kannada and colloquial Tamil uses this word as 'Vaayil'. In a 1st-century CE Tamil inscription, there is a personal reference to ayjayya, a word of Kannada origin. In a 3rd-century CE Tamil inscription there is usage of oppanappa vIran. Here the honorific appa to a person's name is an influence from Kannada. Another word of Kannada origin is taayviru and is found in a 4th-century CE Tamil inscription. S. Settar studied the sittanvAsal inscription of first century CE as also the inscriptions at tirupparamkunram, adakala and neDanUpatti. The later inscriptions were studied in detail by Iravatham Mahadevan also. Mahadevan argues that the words erumi, kavuDi, poshil and tAyiyar have their origin in Kannada because Tamil cognates are not available. Settar adds the words nADu and iLayar to this list. Mahadevan feels that some grammatical categories found in these inscriptions are also unique to Kannada rather than Tamil. Both these scholars attribute these influences to the movements and spread of Jainas in these regions. These inscriptions belong to the period between the first century BCE and fourth century CE. These are some examples that are proof of the early usage of a few Kannada origin words in early Tamil inscriptions before the common era and in the early centuries of the common era.[38]

In the 150 CE Prakrit book Gaathaa Saptashati, written by Haala Raja, Kannada words like tIr or Teer (meaning to be able), tuppa, peTTu, poTTu, poTTa, piTTu (meaning to strike), Pode (Hode) have been used. On the Pallava Prakrit inscription of 250 CE of Hire Hadagali's Shivaskandavarman, the Kannada word kOTe transforms into koTTa. In the 350 CE Chandravalli Prakrit inscription, words of Kannada origin like punaaTa, puNaDa have been used. In one more Prakrit inscription of 250 CE found in Malavalli, Kannada towns like vEgooraM (bEgooru), kundamuchchaMDi find a reference.[26][39]

Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 CE) was a naval and army commander in the early Roman Empire. He writes about pirates between Muziris and Nitrias (Netravati River). He also mentions Barace (Barcelore). Nitrias of Pliny and Nitran of Ptolemy refer to the Netravati River as also the modern port city of Mangaluru, upon its mouth. Many of these are Kannada origin names of places and rivers of the Karnataka coast of 1st century CE.[40][41][42]

The Greek geographer Ptolemy (150 CE) mentions places such as Badiamaioi (Badami), Inde (Indi), Kalligeris (Kalkeri), Modogoulla (Mudagal), Petrigala (Pattadakal), Hippokoura (Huvina Hipparagi), Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Tiripangalida (Gadahinglai), Soubouttou or Sabatha (Savadi), Banaouase (Banavasi), Thogorum (Tagara), Biathana (Paithan), Sirimalaga (Malkhed), Aloe (Ellapur) and Pasage (Palasige) indicating prosperous trade between Egypt, Europe and Karnataka. He also mentions Pounnata (Punnata) and refers to beryls, i.e., the Vaidhurya gems of that country. He mentions Malippala (Malpe), a coastal town of Karnataka. In this work Larika and Kandaloi are identified as Rastrika and Kuntala. Ptolemy writes that "in the midst of the false mouth and the Barios, there is a city called Maganur" (Mangalore). He mentions inland centres of pirates called Oloikhora (Alavakheda). He mentions Ariake Sadinon, meaning Aryaka Satakarni, and Baithana as the capital of Siro(e) P(t)olmaios, i.e., Sri Pulimayi, clearly indicating his knowledge of the Satavahana kings. The word Pulimayi means One with body of Tiger in Kannada, which bears testimony to the possible Kannada origin of Satavahana kings.[43][44]

A possibly more definite reference to Kannada is found in the 'Charition Mime' ascribed to the late 1st to early 2nd century CE.[45][46] The farce, written by an unknown author, is concerned with a Greek lady named Charition who has been stranded on the coast of a country bordering the Indian Ocean. The king of this region, and his countrymen, sometimes use their own language, and the sentences they speak could be interpreted as Kannada, including Koncha madhu patrakke haki ("Having poured a little wine into the cup separately") and paanam beretti katti madhuvam ber ettuvenu ("Having taken up the cup separately and having covered it, I shall take wine separately.").[47] The language employed in the papyrus indicates that the play is set in one of the numerous small ports on the western coast of India, between Karwar and Kanhangad (presently in Kerala).[47] The character of the king in this farce refers to himself as 'the Nayaka of Malpe (Malpi-naik)'. B. A. Saletore identifies the site of this play as Odabhandeshwara or Vadabhandeshwara (ship-vessel-Ishwara or God), situated about a mile from Malpe, which was a Shaivite centre originally surrounded by a forest with a small river passing through it. He rejects M. Govinda Pai's opinion that it must have occurred at Udyavara (Odora in Greek), the capital of Alupas.[48] Stavros J. Tsitsiridis mentions in his research work that Charition is not an exclusively prose or verse text, but a mixed form. The corrupt lines indicate that the text found at Oxyrhynchus (Egypt) has been copied, meaning that the original was even earlier in date. Wilamowitz (1907) and Andreassi (2001) say that for more precise dating of the original, some place the composition of the work as early as in the Hellenistic period (332–30 BCE), others at a later date, up to the early 2nd century CE.[49]

Epigraphy

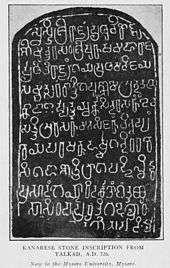

The earliest examples of a full-length Kannada language stone inscription (shilaashaasana) containing Brahmi characters with characteristics attributed to those of proto-Kannada in Hale Kannada (lit Old Kannada) script can be found in the Halmidi inscription, usually dated c. AD 450, indicating that Kannada had become an administrative language at that time. The Halmidi inscription provides invaluable information about the history and culture of Karnataka.[50][51][52][53] The Kannada Lion balastrade inscription excavated at the Pranaveshwara temple complex at Talagunda near Shiralakoppa of Shivamogga district, dated to 370–380 CE is now considered the earliest Kannada inscriptions replacing the Halmidi inscription of 450 CE.[54] The 5th century Tamatekallu inscription of Chitradurga and the Siragunda inscription from Chikkamagaluru Taluk of 500 AD are further examples.[55][56][57] Recent reports indicate that the Old Kannada Nishadi inscription discovered on the Chandragiri hill, Shravanabelagola, is older than Halmidi inscription by about fifty to hundred years and may belong to the period AD 350–400.[58] The noted archaeologist and art historian S. Shettar is of the opinion that an inscription of the Western Ganga King Kongunivarma Madhava (c. 350–370) found at Tagarthi (Tyagarthi) in Shikaripura taluk of Shimoga district is of 350 CE and is also older than the Halmidi inscription.[59][60]

Current estimates of the total number of existing epigraphs written in Kannada range from 25,000 by the scholar Sheldon Pollock to over 30,000 by the Amaresh Datta of the Sahitya Akademi.[61][62] Prior to the Halmidi inscription, there is an abundance of inscriptions containing Kannada words, phrases and sentences, proving its antiquity. The 543 AD Badami cliff inscription of Pulakesi I is an example of a Sanskrit inscription in old Kannada script.[63][64] Kannada inscriptions are not only discovered in Karnataka but also quite commonly in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. Some inscriptions were also found in Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat. The northernmost Kannada inscription of the Rashtrakutas of 964 CE is the Jura record found near Jabalpur in present-day Madhya Pradesh, belonging to the reign of Krishna III. This indicates the spread of the influence of the language over the ages, especially during the rule of large Kannada empires.[65] Pyu sites of Myanmar yielded variety of Indian scripts including those written in a script especially archaic, most resembling the Kadamba (Kannada-speaking Kadambas of 4th century CE Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh[66]) form of common Kannada-Telugu script from Andhra Pradesh.[67][68]

The earliest copper plates inscribed in Old Kannada script and language, dated to the early 8th century AD, are associated with Alupa King Aluvarasa II from Belmannu (the Dakshina Kannada district), and display the double crested fish, his royal emblem.[69] The oldest well-preserved palm leaf manuscript in Old Kannada is that of Dhavala. It dates to around the 9th century and is preserved in the Jain Bhandar, Mudbidri, Dakshina Kannada district.[70] The manuscript contains 1478 leaves written using ink.[70]

Coins

Some early Kadamba Dynasty coins bearing the Kannada inscription Vira and Skandha were found in Satara collectorate.[71] A gold coin bearing three inscriptions of Sri and an abbreviated inscription of king Bhagiratha's name called bhagi (c. AD 390–420) in old Kannada exists.[72] A Kadamba copper coin dated to the 5th century AD with the inscription Srimanaragi in Kannada script was discovered in Banavasi, Uttara Kannada district.[73] Coins with Kannada legends have been discovered spanning the rule of the Western Ganga Dynasty, the Badami Chalukyas, the Alupas, the Western Chalukyas, the Rashtrakutas, the Hoysalas, the Vijayanagar Empire, the Kadamba Dynasty of Banavasi, the Keladi Nayakas and the Mysore Kingdom, the Badami Chalukya coins being a recent discovery.[74][75][76] The coins of the Kadambas of Goa are unique in that they have alternate inscription of the king's name in Kannada and Devanagari in triplicate,[77] a few coins of the Kadambas of Hangal are also available.[78]

Literature

Old Kannada

The oldest existing record of Kannada poetry in Tripadi metre is the Kappe Arabhatta record of AD 700.[79] Kavirajamarga by King Nripatunga Amoghavarsha I (AD 850) is the earliest existing literary work in Kannada. It is a writing on literary criticism and poetics meant to standardise various written Kannada dialects used in literature in previous centuries. The book makes reference to Kannada works by early writers such as King Durvinita of the 6th century and Ravikirti, the author of the Airhole record of 636 AD.[80][81] Since the earliest available Kannada work is one on grammar and a guide of sorts to unify existing variants of Kannada grammar and literary styles, it can be safely assumed that literature in Kannada must have started several centuries earlier.[80][82] An early extant prose work, the Vaddaradhane (ವಡ್ಡಾರಾಧನೆ) by Shivakotiacharya of AD 900 provides an elaborate description of the life of Bhadrabahu of Shravanabelagola.[83]

Kannada works from earlier centuries mentioned in the Kavirajamarga are not yet traced. Some ancient texts now considered extinct but referenced in later centuries are Prabhrita (AD 650) by Syamakundacharya, Chudamani (Crest Jewel—AD 650) by Srivaradhadeva, also known as Tumbuluracharya, which is a work of 96,000 verse-measures and a commentary on logic (Tatwartha-mahashastra).[84][85][86] Other sources date Chudamani to the 6th century or earlier.[87][88] The Karnateshwara Katha, a eulogy for King Pulakesi II, is said to have belonged to the 7th century; the Gajastaka, a work on elephant management by King Shivamara II, belonged to the 8th century,[89] and the Chandraprabha-purana by Sri Vijaya, a court poet of King Amoghavarsha I, is ascribed to the early 9th century.[90] Tamil Buddhist commentators of the 10th century AD (in the commentary on Nemrinatham, a Tamil grammatical work) make references that show that Kannada literature must have flourished as early as the BC 4th century.[91]

Around the beginning of the 9th century, Old Kannada was spoken from Kaveri to Godavari. The Kannada spoken between the rivers Varada and Malaprabha was the pure well of Kannada undefiled.[92]

The late classical period gave birth to several genres of Kannada literature, with new forms of composition coming into use, including Ragale (a form of blank verse) and meters like Sangatya and Shatpadi. The works of this period are based on Jain and Hindu principles. Two of the early writers of this period are Harihara and Raghavanka, trailblazers in their own right. Harihara established the Ragale form of composition while Raghavanka popularised the Shatpadi (six-lined stanza) meter.[93] A famous Jaina writer of the same period is Janna, who expressed Jain religious teachings through his works.[94]

The Vachana Sahitya tradition of the 12th century is purely native and unique in world literature, and the sum of contributions by all sections of society. Vachanas were pithy poems on that period's social, religious and economic conditions. More importantly, they held a mirror to the seed of social revolution, which caused a radical re-examination of the ideas of caste, creed and religion. Some of the important writers of Vachana literature include Basavanna, Allama Prabhu and Akka Mahadevi.[95]

Emperor Nripatunga Amoghavarsha I of 850 CE recognised that the Sanskrit style of Kannada literature was Margi (formal or written form of language) and Desi (folk or spoken form of language) style was popular and made his people aware of the strength and beauty of their native language Kannada. In 1112 CE, Jain poet Nayasena of Mulugunda, Dharwad district, in his Champu work Dharmamrita (ಧರ್ಮಾಮೃತ), a book on morals, warns writers from mixing Kannada with Sanskrit by comparing it with mixing of clarified butter and oil. He has written it using very limited Sanskrit words which fit with idiomatic Kannada. In 1235 CE, Jain poet Andayya, wrote Kabbigara Kava- ಕಬ್ಬಿಗರ ಕಾವ (Poet's Defender), also called Sobagina Suggi (Harvest of Beauty) or Madana-Vijaya and Kavana-Gella (Cupid's Conquest), a Champu work in pure Kannada using only indigenous (desya) Kannada words and the derived form of Sanskrit words – tadbhavas, without the admixture of Sanskrit words. He succeeded in his challenge and proved wrong those who had advocated that it was impossible to write a work in Kannada without using Sanskrit words. Andayya may be considered as a protector of Kannada poets who were ridiculed by Sanskrit advocates. Thus Kannada is the only Dravidian language which is not only capable of using only native Kannada words and grammar in its literature (like Tamil), but also use Sanskrit grammar and vocabulary (like Telugu, Malayalam, Tulu, etc.) The Champu style of literature of mixing poetry with prose owes its origins to the Kannada language which was later incorporated by poets into Sanskrit and other Indian languages.[96][97][98][99][100][101]

Middle Kannada

During the period between the 15th and 18th centuries, Hinduism had a great influence on Middle Kannada (Nadugannada- ನಡುಗನ್ನಡ) language and literature. Kumara Vyasa, who wrote the Karnata Bharata Kathamanjari (ಕರ್ಣಾಟ ಭಾರತ ಕಥಾಮಂಜರಿ), was arguably the most influential Kannada writer of this period. His work, entirely composed in the native Bhamini Shatpadi (hexa-meter), is a sublime adaptation of the first ten books of the Mahabharata.[102] During this period, the Sanskritic influence is present in most abstract, religious, scientific and rhetorical terms.[103][104][105] During this period, several Hindi and Marathi words came into Kannada, chiefly relating to feudalism and militia.[106]

Hindu saints of the Vaishnava sect such as Kanakadasa, Purandaradasa, Naraharitirtha, Vyasatirtha, Sripadaraya, Vadirajatirtha, Vijaya Dasa, Jagannatha Dasa, Prasanna Venkatadasa produced devotional poems in this period.[107] Kanakadasa's Ramadhanya Charite (ರಾಮಧಾನ್ಯ ಚರಿತೆ ) is a rare work, concerning with the issue of class struggle.[108] This period saw the advent of Haridasa Sahitya (lit Dasa literature) which made rich contributions to Bhakti literature and sowed the seeds of Carnatic music. Purandara Dasa is widely considered the Father of Carnatic music.[109][110][111]

Modern Kannada

The Kannada works produced from the 19th century make a gradual transition and are classified as Hosagannada or Modern Kannada. Most notable among the modernists was the poet Nandalike Muddana whose writing may be described as the "Dawn of Modern Kannada", though generally, linguists treat Indira Bai or Saddharma Vijayavu by Gulvadi Venkata Raya as the first literary works in Modern Kannada. The first modern movable type printing of "Canarese" appears to be the Canarese Grammar of Carey printed at Serampore in 1817, and the "Bible in Canarese" of John Hands in 1820.[112] The first novel printed was John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, along with other texts including Canarese Proverbs, The History of Little Henry and his Bearer by Mary Martha Sherwood, Christian Gottlob Barth's Bible Stories and "a Canarese hymn book."[113]

Modern Kannada in the 20th century has been influenced by many movements, notably Navodaya, Navya, Navyottara, Dalita and Bandaya. Contemporary Kannada literature has been highly successful in reaching people of all classes in society. Further, Kannada has produced a number of prolific and renowned poets and writers such as Kuvempu, Bendre, and V K Gokak. Works of Kannada literature have received eight Jnanpith awards,[114] the highest number awarded to any Indian language.[115]

Areas of influence

Besides being the official and administrative language of the state of Karnataka, Kannada language is present in other areas:

- Kannadigas form Tamil Nadu's 3rd biggest linguistic group and add up to about 1.23 million which is 2.2% of Tamil Nadu's total population.[116][117]

- Kannadigas account for 3% of Mumbai's population of 12 million as of 1991, which is 360,000.

- As of 2001, there were 1.26 million Kannada speakers in Maharashtra, 1.3% of its population.

- Kannada is the third-most spoken language in Hyderabad and is spoken by 677,245 people in Andhra Pradesh, some 0.8% of its total population.

- Kannada speakers in Kerala numbered 325,571 which is 1.2% of its population as of 2001.

- Goa has 7% Kannada speakers which accounts for 94,360 Kannadigas.

- There are 43 Kannadigas on the Lakshadweep islands. Amindivi islands were formerly a part of undivided Dakshina Kannada district. The Malayalam spoken by people of Lakshadweep has many Kannada words.[118][119]

- New Delhi has approximately 11,027 Kannada speakers[119][120] or less than 100,000 according to a different source.[121]

- As on 2001, Gujarat had 15,202 Kannada speakers; Madhya Pradesh had 6,039; Rajasthan had 5,651; Punjab had 4,872; Jammu & Kashmir had 4,058; Assam had 2,666; Haryana had 2,115; Chhattisgarh had 2,084; Pondicherry had 1,177; Uttarakhand had 849; Dadra & Nagar Haveli had 728; Tripura had 640; Himachal Pradesh had 608; Arunachal Pradesh had 549; Chandigarh had 451; Nagaland had 398; Daman & Diu had 396; Andaman & Nicobar Islands had 321; Manipur had 239; Meghalaya had 232; Mizoram had 178 and Sikkim had 162. The states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand and Odisha had not properly enumerated Kannada speakers in the census.[119]

- There are about 150,000 Kannadigas in North America (USA and Canada).[122]

- Gulf countries of Middle-East, UK and Australia have minority numbers of Kannada speakers.

Dialects

There is also a considerable difference between the spoken and written forms of the language. Spoken Kannada tends to vary from region to region. The written form is more or less consistent throughout Karnataka. The Ethnologue reports "about 20 dialects" of Kannada. Among them are Kundagannada (spoken exclusively in Kundapura, Brahmavara, Bynduru and Hebri), Nadavar-Kannada (spoken by Nadavaru), Havigannada (spoken mainly by Havyaka Brahmins), Are Bhashe (spoken by Gowda community mainly in Madikeri and Sullia region of Dakshina Kannada), Malenadu Kannada (Sakaleshpur, Coorg, Shimoga, Chikmagalur), Sholaga, Gulbarga Kannada, Dharawad Kannada etc. All of these dialects are influenced by their regional and cultural background. The one million Komarpants in and around Goa speak their own dialect of Kannada, known as Halegannada. They are settled throughout Goa state, throughout Uttara Kannada district and Khanapur taluk of Belagavi district, Karnataka.[123][124][125] The Halakki Vokkaligas of Uttara Kannada, Shimoga and Dakshina Kannada districts of Karnataka speak in their own dialect of Kannada called Halakki Kannada or Achchagannada. Their population estimate is about 75,000.[126][127][128]

Ethnologue also classifies a group of four languages related to Kannada, which are, besides Kannada proper, Badaga, Holiya, Kurumba and Urali.[129]

Nasik district of Maharashtra has a distinct tribe called 'Hatkar Kaanadi' people who speak a Kannada (Kaanadi) dialect with lot of old Kannada words. Per Chidananda Murthy, they are the native people of Nasik from ancient times which shows that North Maharashtra's Nasik area had Kannada population 1000 years ago.[130] [131] Kannada speakers formed 0.12% of Nasik district's population as per 1961 census.[132]

Status

The Director of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Udaya Narayana Singh, submitted a report in 2006 to the Indian government arguing for Kannada to be made a classical language of India.[133] In 2008 the Indian government announced that Kannada was to be designated as one of the classical languages of India.[21][22]

Writing system

The language uses forty-nine phonemic letters, divided into three groups: swaragalu (vowels – thirteen letters); vyanjanagalu (consonants – thirty-four letters); and yogavaahakagalu (neither vowel nor consonant – two letters: anusvara ಂ and visarga ಃ). The character set is almost identical to that of other Indian languages. The Kannada script is almost perfectly phonetic, but for the sound of a "half n" (which becomes a half m). The number of written symbols, however, is far more than the forty-nine characters in the alphabet, because different characters can be combined to form compound characters (ottakshara). Each written symbol in the Kannada script corresponds with one syllable, as opposed to one phoneme in languages like English. The Kannada script is syllabic.

Dictionary

Kannada–Kannada dictionary has existed in Kannada along with ancient works of Kannada grammar. The oldest available Kannada dictionary was composed by the poet 'Ranna' called 'Ranna Kanda' (ರನ್ನ ಕಂದ) in 996 ACE. Other dictionaries are 'Abhidhana Vastukosha' (ಅಭಿದಾನ ವಾಸ್ತುಕೋಶ) by Nagavarma (1045 ACE), 'Amarakoshada Teeku'(ಅಮರಕೋಶದ ತೀಕು) by Vittala (1300), 'Abhinavaabhidaana'(ಅಭಿನವಾಭಿದಾನ) by Abhinava Mangaraja (1398 ACE) and many more.[134] A Kannada–English dictionary consisting of more than 70,000 words was composed by Ferdinand Kittel.[135]

G. Venkatasubbaiah edited the first modern Kannada–Kannada dictionary, a 9,000-page, 8-volume series published by the Kannada Sahitya Parishat. He also wrote a Kannada–English dictionary and a kliṣtapadakōśa (ಕ್ಲಿಷ್ಟಪಾದಕೋಶ), a dictionary of difficult words.[136][137]

Phonology

Kannada has 34 consonants and 13 vowels.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m (ಮ) | n (ನ) | ɳ (ಣ) | ɲ (ಞ) | ŋ (ಙ) | ||

| Stop | voiceless | p (ಪ) | t (ತ) | ʈ (ಟ) | tʃ (ಚ) | k (ಕ) | |

| aspirated | pʰ (ಫ) | tʰ (ಥ) | ʈʰ (ಠ) | tʃʰ (ಛ) | kʰ (ಖ) | ||

| voiced | b (ಬ) | d (ದ) | ɖ (ಡ) | dʒ (ಜ) | ɡ (ಗ) | ||

| breathy | bʱ (ಭ) | dʱ (ಧ) | ɖʱ (ಢ) | dʒʱ (ಝ) | ɡʱ (ಘ) | ||

| Fricative | s (ಸ) | ʂ (ಷ) | ʃ (ಶ) | h (ಹ) | |||

| Approximant | ʋ (ವ) | l (ಲ) | ɭ (ಳ) | j (ಯ) | |||

| Trill | r (ರ) | ||||||

Additionally, Kannada included the following phonemes, which dropped out of common usage in the 12th and 18th century respectively:

- r ಱ (ṟ), the retroflex rhotic.

- ɻ ೞ (ḻ), the retroflex central approximant.

Grammar

The canonical word order of Kannada is SOV (subject–object–verb) as is the case with Dravidian languages. Kannada is a highly inflected language with three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter or common) and two numbers (singular and plural). It is inflected for gender, number and tense, among other things. The most authoritative known book on old Kannada grammar is Shabdhamanidarpana by Keshiraja. The first available Kannada book, a treatise on poetics, rhetoric and basic grammar is the Kavirajamarga from 850 C.E.

The most influential account of Kannada grammar is Keshiraja's Shabdamanidarpana (c. AD 1260).[138][139] The earlier grammatical works include portions of Kavirajamarga (a treatise on alańkāra) of the 9th century, and Kavyavalokana and Karnatakabhashabhushana (both authored by Nagavarma II in the first half of the 12th century).[139]

Compound bases

Compound bases, called samāsa in Kannada, are a set of two or more words compounded together.[140] There are several types of compound bases, based on the rules followed for compounding. The types of compound bases or samāsas: tatpurusha, karmadhāraya, dvigu, bahuvreehi, anshi, dvandva, kriya and gamaka samāsa. Examples: taṅgāḷi, hemmara, kannusanne.

Pronouns

In many ways the third-person pronouns are more like demonstratives than like the other pronouns. They are pluralized like nouns and whereas the first- and second-person pronouns have different ways to distinguish number.[141]

Sample text

The given sample text is Article 1 from the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights Declaration.[142]

Kannada script

ಎಲ್ಲಾ ಮಾನವರೂ ಸ್ವತಂತ್ರರಾಗಿಯೇ ಹುಟ್ಟಿದ್ದಾರೆ. ಹಾಗೂ ಘನತೆ ಮತ್ತು ಹಕ್ಕುಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಸಮಾನರಾಗಿದ್ದಾರೆ. ತಿಳಿವು ಮತ್ತು ಅಂತಃಕರಣಗಳನ್ನು ಪಡೆದವರಾದ್ದರಿಂದ, ಅವರು ಒಬ್ಬರಿಗೊಬ್ಬರು ಸಹೋದರ ಭಾವದಿಂದ ನಡೆದುಕೊಳ್ಳಬೇಕು.

Transliteration

Ellā mānavarū svatantrarāgiyē huttiddare. Hāgū bhanate mattu hakku gaḷalli samānarāgiddāre. Thilivu mattu antaḥkaraṇagaḷannu paḍedavarāddarinda avaru obbarigobbaru sahōdara bhāvadinda nadedhukollabeku.

Translation

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

Notes

- Garg, Ganga Ram (1992) [1992]. "Kannada literature". Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World: A-Aj, Volume 1. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-374-0.

- Kuiper, Kathleen, ed. (2011). "Dravidian Studies: Kannada". Understanding India-The Culture of India. New York: Britannica educational Printing. ISBN 978-1-61530-203-1.

- Steever, S. B. (1998). "Kannada". In Steever, S. B. (ed.). The Dravidian Languages (Routledge Language Family Descriptions). London: Routledge. Pp. 436. pp. 129–157. ISBN 978-0-415-10023-6.

- Kloss and McConnell, Heinz and Grant D. (1978). The Written languages of the world: a survey of the degree and modes of use-vol 2 part1. Université Laval. ISBN 978-2-7637-7186-1.

- Narasimhacharya, R (1988) [1988]. History of Kannada Literature. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0303-5.

- Narasimhacharya, R. (1934) History of Kannada Language. University of Mysore.

- Rice, E.P. (1982) [1921]. Kannada Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0063-8.

- Rice, B.L. (2001) [1897]. Mysore Gazetteer Compiled for Government-vol 1. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0977-8.

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2002) [2001]. A concise history of Karnata.k.a. from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter books. LCCN 80905179. OCLC 7796041.

- Various (1988) [1988]. Encyclopaedia of Indian literature-vol 2. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0.

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A. (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-560686-7.

- Ramesh, K.V. (1984) [1984]. Chalukyas of Vatapi. New Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

- Kittel, F (1993) [1993]. A Grammar of the Kannada Language Comprising the Three Dialects of the Language (Ancient, Medieval and Modern). New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0056-0.

- Bhat, Thirumaleshwara (1993) [1993]. Govinda Pai. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-7201-540-4.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1973) [1973]. Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. Leiden, Netherlands: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-03591-1.

- Shapiro and Schiffman, Michael C., Harold F. (1981) [1981]. Language And Society in South Asia. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-2607-6.

References

- Kannada at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

- "Statement 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother} tongues – 2011". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Zvelebil (fig. 36) and Krishnamurthy (fig. 37) in Shapiro and Schiffman (1981), pp. 95–96

- The Karnataka official language act, 1963 – Karnataka Gazette (Extraordinary) Part IV-2A. Government of Karnataka. 1963. p. 33.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Kannada". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). "Currency of Selected Languages and Scripts". A Historical Atlas of South Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0195068696.

- "Kannada". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "Kannada". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Kanarese | Definition of Kanarese by Lexico".

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kanarese

- "Census 2011: Languages by state" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "Indiaspeak: English is our 2nd language". Times of India.

- "The Karnataka Official Language Act" (PDF). Official website of Department of Parliamentary Affairs and Legislation. Government of Karnataka. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- "Gangas of Talakad". Official website of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, India. classicalkannada.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- "Rastrakutas". Official website of the Central Institute of Indian Languages. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- Zvelebil (1973), p. 7 (Introductory, chart)

- Garg (1992), p. 67

- "Jnanpeeth Awardees from Karnataka | Jnanapeeta Awardees | Jnanpith Award".

- "Jnanpith Award: Eight Kannada authors who have won 'Jnanpith Award'". 5 September 2017.

- "Jnanpith Awards Winners Full List". 27 July 2016.

- Kuiper (2011), p. 74

- R Zydenbos in Cushman S, Cavanagh C, Ramazani J, Rouzer P, The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition, p. 767, Princeton University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-691-15491-6

- "IBNLive – CIIL to head Centre for classical Kannada study". ibnlive.in.com. 23 July 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Steever, S. B. (1998), p. 129

- "Classical Kannada, Antiquity of Kannada". Centre for classical Kannada. Central Institute for Indian Languages. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century AD. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674012271. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- Mythic Society (Bangalore, India) (1985). The quarterly journal of the Mythic society (Bangalore)., Volume 76. Mythic Society (Bangalore, India). pp. Pages_197–210.

- B. K. Khadabadi; Prākr̥ta Bhāratī Akādamī (1997). Studies in Jainology, Prakrit literature, and languages: a collection of select 51 papers Volume 116 of Prakrit Bharti pushpa. Prakrit Bharati Academy. pp. 444 pages.

- Jha, Ganganatha (1976). Journal of the Ganganatha Jha Kendriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha, Volume 32. Ganganatha Jha Kendriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha. pp. see page 319.

- Kulli, Jayavant S (1991). History of grammatical theories in Kannada. Internationial School of Dravidian Linguistics. pp. 330 pages.

- K R, Subramanian (2002). Origin of Saivism and Its History in the Tamil Land. Asian Educational Services. p. 11. ISBN 9788120601444.

- Kamath (2001), p. 5–6

- Wilks in Rice, B.L. (1897), p490

- Shashidhar, Dr. Melkunde (2016). A HISTORY OF FREEDOM AND UNIFICATION MOVEMENT IN KARNATAKA. United States: Lulu publication. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-329-82501-7.

- Pai and Narasimhachar in Bhat (1993), p103

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. India: New Age International. p. 360. ISBN 9788122411980.

- The word Isila found in the Ashokan inscription (called the Brahmagiri edict from Karnataka) meaning to shoot an arrow, is a Kannada word, indicating that Kannada was a spoken language in the 3rd century BCE (D.L. Narasimhachar in Kamath 2001, p5)

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy. ISBN 9780674012271.

- "Karnataka history" (PDF). ShodhGanga.

- Chattopadhyaya, Sudhakar (1 January 1974). Some Early Dynasties of South India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120829411.

- "Muziris Heritage Project".

- Warmington, E. H. (1928). The Commerce between the Roman Empire and India. Cambridge University Press, 2014. pp. 112–113. ISBN 9781107432147.

- "Story of Kannadiga, Kannada and Karnataka. Glimpses of Kannada History and Greatness". 8 April 2009.

- A. Smith, Vincent; Williams Jackson, A. V. (1 January 2008). History of India, in Nine Volumes: Vol. II – From the Sixth Century B.C. to the Mohammedan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great. Cosimo, Inc., 2008. pp. 193–196. ISBN 9781605204925.

- Suryanatha Kamath – Karnataka State Gazetteer – South Kanara (1973), Printed by the Director of Print, Stationery and Publications at the Govt. Press

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande – History of Indian theatre, Volume 3 (1987), Abhinav Publications, New Delhi.

- D. R. Bhandarkar – Lectures on the Ancient History of India on the Period From 650 To 320 B.C. (1919), University of Calcutta.

- Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1981). Ancient Indian And Indo-Greek Theatre. Abhinav Publications. pp. 98–110. ISBN 8170171474.

- Tsitsiridis, Stavros J. (2011). "GREEK MIME IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE (P.Oxy. 413)". Greek Mime in the Roman Empire: 184–189.

- Ramesh (1984), p10

- Encyclopaedia of Indian literature vol. 2, Sahitya Akademi (1988), p1717, p 1474

- A report on Halmidi inscription, Muralidhara Khajane (3 November 2003). "Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- Kamath (2001), p10

- "Kannada inscription at Talagunda of 370 CE may replace Halmidi inscription as the oldest". Deccan Herald.

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p6

- Rice (1921), p13

- Govinda Pai in Bhat (1993), p102

- "Mysore scholar deciphers Chandragiri inscription". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- "HALMIDI INSCRIPTION". Centre for classical Kannada. Central Institute for Indian Languages. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- "HISTORIAN'S STUDY PUSHES EARLIEST RECORD OF KANNADA WRITING BACK BY A CENTURY". The antiquity of Kannada. 10 March 2013.

- Datta, Amaresh; Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 2, p.1717, 1988, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 81-260-1194-7

- Sheldon Pollock in Dehejia, Vidya; The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art, p.5, chapter:The body as Leitmotif, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14028-7

- Kamath (2001), p58

- Azmathulla Shariff (14 February 2018). "Badami: Chalukyans' magical transformation". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 7 October 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- Kamath (2001), p83

- Sircar 1965. pp. 202–4.

- Luce 1985. pp. 62, n.16.

- Guy, John (1996). "A WARRIOR-RULER STELE FROM SRI KSETRA, PYU, BURMA" (PDF). Journal of The Siam Society – Siamese Heritage. Journal of The Siam Society.

- Gururaj Bhat in Kamath (2001), p97

- Mukerjee, Shruba (21 August 2005). "Preserving voices from the past". Sunday Herald. Archived from the original on 22 October 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- The coins are preserved at the Archaeological Section, Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, Mumbai – Kundangar and Moraes in Moraes (1931), p382

- The coin is preserved at the Indian Historical Research Institute, St. Xavier's College, Mumbai – Kundangar and Moraes in Moraes (1938), p 382

- Dr Gopal, director, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History (6 February 2006). "5th century copper coin discovered at Banavasi". The Hindu. Chennai, India.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kamath (2001), p12, p57

- Govindaraya Prabhu, S. "Indian coins-Dynasties of South". Prabhu's Web Page on Indian Coinage, 1 November 2001. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- Harihariah Oruganti-Vice-President; Madras Coin Society. "Vijayanagar Coins-Catalogue". Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- This shows that the native vernacular of the Goa Kadambas was Kannada – Moraes (1931), p384

- Two coins of the Hangal Kadambas are preserved at the Royal Asiatic Society, Mumbai, one with the Kannada inscription Saarvadhari and other with Nakara. Moraes (1931), p385

- Kamath (2001), p67

- Sastri (1955), p355

- Kamath (2001), p90

- Jyotsna Kamat. "History of the Kannada Literature-I". Kamat's Potpourri, 4 November 2006. Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- Sastri (1955), p356

- The seventeenth-century Kannada grammarian Bhattakalanka wrote about the Chudamani as a milestone in the literature of the Kannada language (Sastri (1955), p355)

- Jyotsna Kamat. "History of the Kannada Literature – I". Kamat's Potpourri, 4 November 2006. Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp 4–5

- Rice, B.L. (1897), p497

- 6th century Sanskrit poet Dandin praised Srivaradhadeva's writing as "having produced Saraswati from the tip of his tongue, just as Shiva produced the Ganges from the tip of his top knot (Rice E.P., 1921, p27)

- Kamath (2001), p50, p67

- The author and his work were praised by the latter-day poet Durgasimha of AD 1025 (Narasimhacharya 1988, p18.)

- K. Appadurai. "The place of Kannada and Tamil in India's national culture". INTAMM. Archived from the original on 15 April 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- Narasimhacharya, R. (1999). History of Kannada Language. Asian Educational Services, 1942. ISBN 9788120605596.

- Sastri (1955), pp 361–2

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p20

- Sastri (1955), p361

- Nagendra, Dr. (1988). "Indian Literature". Prabhat Prakashan, 1988.

- Narasimhacharya, Ramanujapuram (1988). History of Kannada Literature: Readership Lectures. Asian Educational Services, 1988. ISBN 9788120603035.

andayya pure kannada.

- Datta, Amaresh (1987). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: A-Devo. Sahitya Akademi, 1987. ISBN 9788126018031.

- Hari Saravanan, V. (2014). Gods, Heroes and their Story Tellers: Intangible cultural heritage of South India. Notion Press, 2014. ISBN 9789384391492.

- Rice, Edward. P (1921), "A History of Kannada Literature", Oxford University Press, 1921: 14–15

- Rice, Edward P. (1982). A History of Kannada Literature. Asian Educational Services. pp. 15, 44. ISBN 9788120600638.

- Sastri (1955), p364

- "Literature in all Dravidian languages owes a great deal to Sanskrit, the magic wand whose touch raised each of the languages from a level of patois to that of a literary idiom". (Sastri 1955, p309)

- Takahashi, Takanobu. 1995. Tamil love poetry and poetics. Brill's Indological library, v. 9. Leiden: E.J. Brill, p16,18

- "The author endeavours to demonstrate that the entire Sangam poetic corpus follows the "Kavya" form of Sanskrit poetry"-Tieken, Herman Joseph Hugo. 2001. Kāvya in South India: old Tamil Caṅkam poetry. Groningen: Egbert Forsten

- J. Bucher; Ferdinand Kittel (1899). A Kannaḍa-English school-dictionary: chiefly based on the labours of the Rev. Dr. F. Kittel. Basel Mission Book & Tract Depository.

- Sastri (1955), pp 364–365

- The writing exalts the grain Ragi above all other grains that form the staple foods of much of modern Karnataka (Sastri 1955, p365)

- Moorthy, Vijaya (2001). Romance of the Raga. Abinav publications. p. 67. ISBN 978-81-7017-382-3.

- Iyer (2006), p93

- Sastri (1955), p365

- Report on the administration of Mysore – Page 90 Mysore – 1864 "There is no authentic record of the casting of the first Early Canarese printing. Canarese type, but a Canarese Grammar by Carey printed at Serampore in 1817 is extant. About the same time a translation of the Scriptures was printed

- Missions in south India – Page 56 Joseph Mullens – 1854 "Among those of the former are tracts on Caste, on the Hindu gods; Canarese Proverbs; Henry and his Bearer; the Pilgrim's Progress; Barth's Bible Stories; a Canarese hymn book"

- Special Correspondent (20 September 2011). "Jnanpith for Kambar". The Hindu.

- "Welcome to: Bhartiya Jnanpith". jnanpith.net. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- Nagarajan, Rema (16 April 2008). "Kannadigas TN's 3rd biggest group". The Times of India.

- Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David (2003). The Territories and States of India. Routledge. pp. 224–226. ISBN 9781135356255.

- Palanithurai, Ganapathy (2002). Dynamics of New Panchayati Raj System in India: Select states. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788180691294.

- "DISTRIBUTION OF 10,000 PERSONS BY LANGUAGE – INDIA, STATES AND UNION TERRITORIES – 2001". Census Data 2001. Government of India. 2001.

- "New Delhi Kannadigas". BangaloreBest.com. Indias-Best.Com Pvt. Ltd. 2013.

- D P, Satish (4 February 2015). "New Delhi South Indians". IBN Live-CNN IBN.

- "North America Kannadigas". AKKA. teksource. 2016.

- Buchanan, Francis Hamilton (1807). A Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara, and Malabar. Volume 3. London: Cadell. ISBN 9781402146756.

- Naik, Vinayak K.; Naik, Yogesh (6 April 2007). "HISTORY OF KOMARPANTHS". hindu-kshatriya-komarpanth. Atom.

- "GOA ON THE THRESHOLD OF THE 20TH CENTURY" (PDF). ShodhGanga. 1995.

- Kamat, K. L. "Halakki Farmers of Uttara Kannada". Kamat's Potpourri.

- Uday, Savita (18 August 2010). "Tribes of Uttara Kannada-The Halakki Tribe". Buda Folklore.

- K., Bhumika (29 October 2014). "Beauty in all its glory" – via The Hindu.

- "Kannada". The Record News. DSAL, Chicago.

- S., Kiran Kumar (17 July 2015). "The Kannada History of Maharashtra".

- "Region between Godavari, Cauvery was once Karnataka". Deccan Herald. 5 November 2014.

- "The People – Population". Nasik District Gazetteers. Government of Maharashtra.

- K.N. Venkatasubba Rao (4 October 2006). "Kannada likely to get classical tag". The Hindu. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- N Ucida and B B Rajpurohit, http://www.aa.tufs.ac.jp/~tjun/data/kandic/kannada-english_dictionary.pdf, Kannada-English Etymological Dictionary

- Manjulakshi & Bhat. "Kannada Dialect Dictionaries and Dictionaries in Subregional Languages of Karnataka". Language in India, Volume 5: 9 September 2005. Central Institute of Indian Languages, University of Mysore. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- Muralidhara Khajane (22 August 2012). "Today's Paper / NATIONAL: 100 years on, words never fail him". The Hindu.

- Johnson Language (20 August 2012). "Language in India: Kannada, threatened at home". The Economist. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Studies in Indian History, Epigraphy, and Culture – By Govind Swamirao Gai, pp. 315

- A Grammar of the Kannada Language. F. Kittel (1993), p. 3.

- Ferdinand Kittel, pp. 30

- Bhat, D.N.S. 2004. Pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 13–14

- "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". www.un.org. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Further reading

- Masica, Colin P. (1991) [1991]. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Thapar, Romila (2003) [2003]. The Penguin History of Early India. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-302989-2.

- George M. Moraes (1931), The Kadamba Kula, A History of Ancient and Medieval Karnataka, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras, 1990 ISBN 81-206-0595-0

- Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1987) [1987]. History of Indian Theatre. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-221-5.

External links

| Kannada edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Kannada at Curlie

- Kannada language at Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition, Muralidhara Khajane". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 3 November 2003. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "Declare Kannada a classical language, Staff reporter". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 27 May 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "The place of Kannada and Tamil in Indias National Culture". Archived from the original on 15 April 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "History of the Kannada Literature (by Jyotsna Kamat)". Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "Records and revelations, Indira Parathasarathy". Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "Ancient inscriptions unearthed, N. Havalaiah". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 24 January 2004. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "Indian inscriptions-South Indian inscriptions, Vol 20, 18, 17, 15, 11 and 9, Archaeological survey of India, What Is India Publishers (P) Ltd".

- "English to Kannada Dictionary".