Geology of Japan

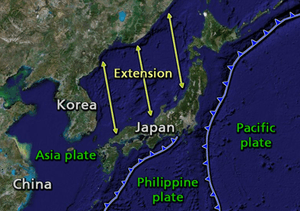

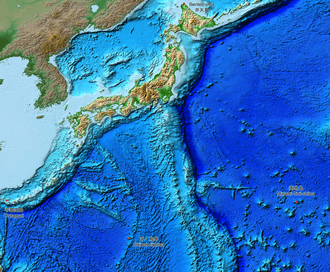

The islands of Japan are primarily the result of several large ocean movements occurring over hundreds of millions of years from the mid-Silurian to the Pleistocene as a result of the subduction of the Philippine Sea Plate beneath the continental Amurian Plate and Okinawa Plate to the south, and subduction of the Pacific Plate under the Okhotsk Plate to the north.

Japan was originally attached to the eastern coast of the Eurasian continent. The subducting plates, being deeper than the Eurasian plate, pulled Japan eastward, opening the Sea of Japan around 15 million years ago.[1] The Strait of Tartary and the Korea Strait opened much later.

Japan is situated in a volcanic zone on the Pacific Ring of Fire. Frequent low intensity earth tremors and occasional volcanic activity are felt throughout the islands. Destructive earthquakes, often resulting in tsunamis, occur several times per century. The most recent major quakes include the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, the 2004 Chūetsu earthquake and the Great Hanshin earthquake of 1995. Hot springs are numerous and have been developed as resorts.

Geological history

Orogeny phase

The breakup of Rodinia about 750 million years ago formed the Panthalassa ocean, with rocks that eventually became Japan sitting on its eastern margin. In the Early Silurian (450 million years ago)[2], the subduction of the oceanic plates started, and this process continues to the present day, forming a roughly 400 km wide orogeny at the convergent boundary. Several (9 or 10) oceanic plates were completely subducted and their remains have formed paired metamorphic belts. The most recent complete subduction of a plate was that of the Izanagi Plate 95 million years ago. Currently the Philippine Sea Plate is subducting beneath the continental Amurian Plate and the Okinawa Plate to the south at a speed of 4 cm/year, forming the Nankai Trough and the Ryukyu Trench. The Pacific Plate is subducting under the Okhotsk Plate to the north at a speed of 10 cm/year. The early stages of subduction-accretion have recycled the continental crust margin several times, leaving the majority of the modern Japanese archipelago composed of rocks formed in the Permian period or later.

Island arc phase

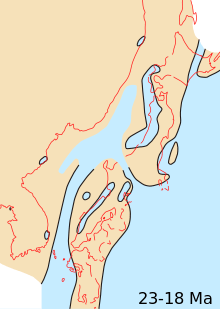

Around 23 million years ago, western Japan was a coastal region of the Eurasia continent. The subducting plates, being deeper than the Eurasian plate, pulled parts of Japan which become modern Chūgoku region and Kyushu eastward, opening the Sea of Japan (simultaneously with the Sea of Okhotsk) around 15-20 million years ago, with likely freshwater lake state before the sea has rushed in.[3] Around 16 million years ago, in the Miocene period, a peninsula attached to the eastern coast of the Eurasian continent was well formed. About 11 million years before present, the parts of Japan which become modern Tōhoku and Hokkaido were gradually uplifted from the seafloor, and terranes of Chūbu region were gradually accreted from the colliding island chains. The Strait of Tartary and the Korea Strait opened much later, about 2 million years ago. At the same time, a severe subduction of Fossa Magna graben have formed the Kantō Plain.[4]

Japanese archipelago, Sea of Japan and surrounding part of continental East Asia in Early Miocene (23-18 Ma)

Japanese archipelago, Sea of Japan and surrounding part of continental East Asia in Early Miocene (23-18 Ma) Japanese archipelago, Sea of Japan and surrounding part of continental East Asia in Middle Pliocene to Late Pliocene (3.5-2 Ma)

Japanese archipelago, Sea of Japan and surrounding part of continental East Asia in Middle Pliocene to Late Pliocene (3.5-2 Ma) Japanese archipelago at the Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago, thin black line indicates present-day shorelinesVegetated landUnvegetated landOcean

Japanese archipelago at the Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago, thin black line indicates present-day shorelinesVegetated landUnvegetated landOcean

Current state

General information

Overall, the geological composition of Japan is poorly understood. The Japanese islands are formed of several geological units parallel to the subduction front. The parts of islands facing oceanic plates are typically younger and display a larger proportion of volcanic products, while the parts facing the Sea of Japan are mostly heavily faulted and folded sedimentary deposits. In north-west Japan, the thick quaternary deposits make determination of the geological history especially difficult.[5]

Geological structure

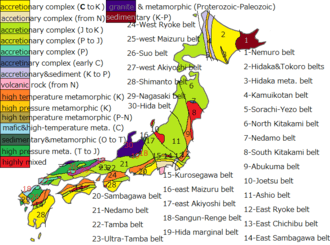

The Japanese islands are divided into three major geological domains:

- Northeastern Japan, north of Tanakura fault (which had high volcanic activity 14-17 million years before present[6])

- Central Japan, between Tanakura fault and Itoigawa-Shizuoka Tectonic Line.

- Fossa Magna graben

- Tanna Fault

- Bōsō Hill Range

- Southwestern Japan, south of Itoigawa-Shizuoka Tectonic Line. The Southwestern Japan is further subdivided into several metamorphic belts stretched along Japan Median Tectonic Line.[7] The parts of Japan north of Japan Median Tectonic Line ("Inner Zone") contains many granitoid fragments dating from Paleogene to Cretaceous period intruding the older material, while south of the line ("Outer Zone") is mostly accretionary complexes of Jurassic period or younger.

- Urasoko fault

- Fukozu Fault

- Neodani Fault

- Nojima Fault

- Hida orogenic belt (Hida Mountains and Ryōhaku Mountains)

- Sangun orogenic belt

- Maizuru orogenic belt

- Tanba-mino orogenic belt

- Ryoke orogenic belt

- Shimanto orogenic belt[8]

- Sambagawa orogenic belt[9]

- Chichibu orogenic belt[10]

- Sambosan orogenic belt

- Beppu–Shimabara graben

Research

The Geology of Japan is handled mostly by Geological Society of Japan, with the following major periodicals:

- The Journal of the Geological Society of Japan - since 1893

- Geological Studies (地質学論集) - since 1968

- Geological Society of Japan News (日本地質学会News) - since 1998

Geological hazards

Japan is in a volcanic zone on the Pacific Ring of Fire. Frequent low intensity earth tremors and occasional volcanic activity are felt throughout the islands. Destructive earthquakes, often resulting in tsunamis, occur several times a century. The most recent major quakes include the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, the 2004 Chūetsu earthquake and the Great Hanshin earthquake of 1995. Hot springs are numerous and have been developed as resorts.

See also

References

- Barnes, Gina L. (2003). "Origins of the Japanese Islands: The New "Big Picture"" (PDF). University of Durham. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- Bor-ming Jahn (2010). "ACCRETIONARY OROGEN AND EVOLUTION OF THE JAPANESE ISLANDS—IMPLICATIONS FROM A Sr-Nd ISOTOPIC STUDY OF THE PHANEROZOIC GRANITOIDS FROM SW JAPAN" (PDF). American Journal of Science, Vol. 310, December, 2010, P. 1210–1249, DOI 10.2475/10.2010.02. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- Barnes, Gina L. (2003). "Origins of the Japanese Islands: The New "Big Picture"" (PDF). University of Durham. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- "Formation history of the Japanese Islands (4) -- GLGArcs". glgarcs.rgr.jp. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- "Geology of Japan|Geological Survey of Japan, AIST|産総研地質調査総合センター / Geological Survey of Japan, AIST". gsj.jp. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- "Yurie SAWAHATA, Makoto Okada, Jun Hosoi, Kazuo Amano, "Paleomagnetic study of Neogene sediments in strike-slip basins along the Tanakura Fault". confit.atlas.jp. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- connelly@geo.arizona.edu. "Southwest Japan". geo.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- A. Taira, H. Okada, J. H. McD. Whitaker & A. J. Smith, The Shimanto Belt of Japan: Cretaceous-lower Miocene active-margin sedimentation

- "Sanbagawa belt (Sambagawa metamorphic belt), Shikoku Island, Japan". mindat.org. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- "Chichibu belt from geo.arizona.edu". geo.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

Further reading

- Hashimoto, M., ed. (1990). Geology of Japan. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 9780792309093.

- T. Moreno; S.R. Wallis; T. Kojima; W. Gibbons (eds.). Geology of Japan (Geological Society of London)(2015). ISBN 978-1862397439.

by - (Author),

- Takai, Fuyuji; Tatsurō Matsumoto; Ryūzō Toriyama (1963). Geology of Japan. University of California Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geology of Japan. |

| External image | |

|---|---|

- National Archives of Japan: Tatoroyama no ki, survey of limestone cave in Mount Tatoro in Kozuke Province, 1837 (Tenpo 8).