Liopleurodon

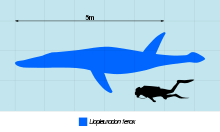

Liopleurodon (/ˌlaɪoʊˈplʊərədɒn/; meaning 'smooth-sided teeth') is a genus of large, carnivorous marine reptile belonging to the Pliosauroidea, a clade of short-necked plesiosaurs. The two species of Liopleurodon lived from the Callovian Stage of the Middle Jurassic to the Kimmeridgian stage of the Late Jurassic Period (c. 166 to 155 mya). It was the apex predator of the Middle to Late Jurassic seas that covered Europe. The largest species, L. ferox, is estimated to have grown up to 6.4 metres (21 ft) in length.[1]

| Liopleurodon | |

|---|---|

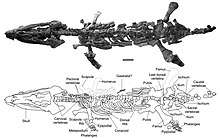

| L. ferox skeleton, Museum of Paleontology, Tübingen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Pliosauridae |

| Clade: | †Thalassophonea |

| Genus: | †Liopleurodon Sauvage, 1873 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The name "Liopleurodon" (meaning "smooth-sided tooth") derives from Ancient Greek words: λεῖος leios, "smooth"; πλευρά pleurá, "side" or "rib"; and ὀδόν odṓn, "tooth".

Discovery and species

The genus name Liopleurodon was coined by Henri Émile Sauvage in 1873 on the basis of very poor remains consisting of three 7 cm (2¾ inch) teeth. One tooth, found near Boulogne-sur-Mer, France in layers dating from the Callovian, was named Liopleurodon ferox, another from Charly, France was named Liopleurodon grossouvrei, while a third discovered near Caen, France was originally described as Poikilopleuron bucklandi and ascribed by Sauvage to the species Liopleurodon bucklandi. Sauvage did not ascribe the genus to any particular group of reptiles in his descriptions.[2]

Liopleurodon fossils have been found mainly in England and France. Fossil specimens that are contemporary (Callovian-Kimmeridgian) with those from England and France referrable to Liopleurodon are known from Germany.[3][4]

Currently, there are two recognized species within Liopleurodon. From the Callovian-Kimmeridgian of England and France L. ferox is well known; while also from the Callovian-Kimmeridgian of England is the rarer L. pachydeirus, described by Seeley (1869) as a species of Pliosaurus (1869).[5] Only L. ferox is known from more or less complete skeletons. Liopleurodon grossouvrei, although synonymized with Pliosaurus andrewsi by most authors, may be a distinct genus in its own right given differences from P. andrewsi and Liopleurodon type species.[6]

Description

Size

Liopleurodon ferox first came to the public attention in 1999 when it was featured in an episode of the BBC television series Walking with Dinosaurs, which depicted it as an enormous 25 m (82 ft) long predator; this was based on very fragmentary remains, and considered to be an exaggeration for Liopleurodon,[7] with the calculations of 20-metre specimens generally considered dubious.[8]

Estimating the size of pliosaurs is difficult because not much is known of their postcranial anatomy. The palaeontologist L. B. Tarlo suggested that their total body length can be estimated from the length of their skull which he claimed was typically one-seventh of the former measurement, applying this ratio to L. ferox suggests that the largest known specimen was a little over 10 m (33 ft) while a more typical size range would be from 5 to 7 m (16 to 23 ft).[7] The body mass has been estimated at 1 and 1.7 t (2,200 and 3,700 lb) for the lengths 4.8 and 7 m (16 and 23 ft) respectively.[9]

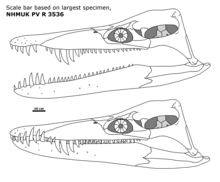

However, additional Kronosaurus specimens[7] and a skeleton of L. ferox, GPIT 1754/2, show that their skulls were actually about one-fifth of their total body length.[1] One specimen, CAMSMJ.27424, has an estimated total length of 6.39 m (21.0 ft). The largest known skull, NHM R3536, at 1.26 m (4.1 ft) in condylobasal length[1] (1.54 m (5.1 ft) in overall length[10]).

Classification

%2C_London_(1910)_(20864103542).jpg)

Liopleurodon belongs to the family Pliosauridae, a clade within Plesiosauria, known from the Jurassic (maybe also from the Cretaceous) of Europe and North America.[9]

Liopleurodon was one of the basal taxa from the Middle Jurassic. Differences between these taxa and their relatives from the Upper Jurassic include alveoli count, smaller skull and smaller body size.[10]

An analysis in 2013 classifies Liopleurodon, Simolestes, Peloneustes, Pliosaurus, Gallardosaurus, and Brachaucheninae as Thalassophonea.[11]

The cladogram below follows a 2011 analysis by paleontologists Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson, and reduced to genera only.[12]

| Pliosauroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeobiology

Four strong paddle-like limbs suggest that Liopleurodon was a powerful swimmer. Its four-flipper mode of propulsion is characteristic of all plesiosaurs. A study involving a swimming robot has demonstrated that although this form of propulsion is not especially efficient, it provides very good acceleration—a desirable trait in an ambush predator.[14][15] Studies of the skull have shown that it could probably scan the water with its nostrils to ascertain the source of certain smells.[16]

References

- Noe, Leslie F.; Jeff Liston; Mark Evans (2003). "The first relatively complete exoccipital-opisthotic from the braincase of the Callovian pliosaur, Liopleurodon" (PDF). Geological Magazine. UK: Cambridge University Press. 140 (4): 479–486. doi:10.1017/S0016756803007829.

- Sauvage, H.E. (1873). "Notes sur les reptiles fossiles. 4. Du genre Liopleurodon Sauvage". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. series 3. 1: 377–380.

- Sachs, S. (1997). "Mesozoische Reptilien aus Nordrhein-Westfalen." Pp. 22-27 in Sachs, S., Rauhut, O.W.M. and Weigert, A. (eds.), Terra Nostra. 1. Treffen der deutschsprachigen Paläoherpetologen Düsseldorf.

- Sachs, Sven; Christian Nyhuis (2015). "Belege für riesige Pliosaurier aus dem Jura Deutschlands" (PDF). Der Steinkern. 21: 74–82.

- Seeley, H.G. (1869). Index to the Fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the Secondary System of Strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge.

- Foffa, D.; Young, M.T.; Brusatte, S.L. (2018). "Filling the Corallian gap: New information on Late Jurassic marine reptile faunas from England" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 63 (2): 287–313. doi:10.4202/app.00455.2018.

- Forrest, Richard (20 November 2007). "Liopleurodon". The Plesiosaur Site. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- "Re: Liopleurodon size".

- McHenry, Colin Richard (2009). "Devourer of Gods: the palaeoecology of the Cretaceous pliosaur Kronosaurus queenslandicus" (PDF): 1–460. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Benson, RBJ; Evans M; Smith AS; Sassoon J; Moore-Faye S; et al. (2013). "A giant pliosaurid skull from the Late Jurassic of England". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): 1–34. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065989. PMC 3669260. PMID 23741520.

- Benson, RBJ; Druckenmiller PS (2013). "Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition". Biological Reviews. 89 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/brv.12038. PMID 23581455.

- Hilary F. Ketchum; Roger B. J. Benson (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01083.x (inactive 2020-01-22).

- Schumacher, B. A.; Carpenter, K.; Everhart, M. J. (2013). "A new Cretaceous Pliosaurid (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Carlile Shale (middle Turonian) of Russell County, Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (3): 613–628. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.722576.

- Long Jr, J. H.; Schumacher, J.; Livingston, N.; Kemp, M. (2006). "Four flippers or two? Tetrapodal swimming with an aquatic robot". Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. 1 (1): 20–29. doi:10.1088/1748-3182/1/1/003. PMID 17671301.

- "Swimming Robot Tests Theories About Locomotion In Existing And Extinct Animals". ScienceDaily. May 30, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Carpenter, K. (1997). "Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American Cretaceous plesiosaurs." Pp. 191–216 in Callaway, J.M. and Nicholls, E.L. (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles. Academic Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liopleurodon. |

- Liopleurodon information and photos, The Plesiosaur Directory

- Article on the giant pliosaur skull once assigned to Liopleurodon, Tetrapod Zoology