Simolestes

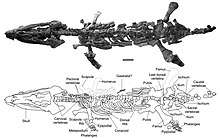

Simolestes (meaning "hearkening thief") is an extinct pliosaurid genus that lived in the Middle to Late Jurassic.[1] The type specimen, BMNH R. 3319 is an almost complete but crushed skeleton diagnostic to Simolestes vorax, dating back to the Callovian of the Oxford Clay formation, England. The genus is also known from the Callovian and Bajocian of France (S.keileni),[2] and the Tithonian of India (S.indicus).[3] The referral of these two species to Simolestes is dubious, however.[4]

| Simolestes | |

|---|---|

| |

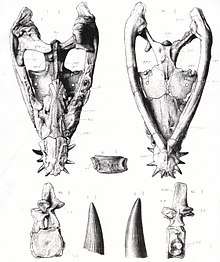

| Diagram of the skull of S. vorax | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Pliosauridae |

| Clade: | †Thalassophonea |

| Genus: | †Simolestes |

| Species | |

| |

Description

Simolestes possessed a short, high, and wide skull which was built to resist torsional forces when hunting.

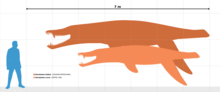

The largest specimens of S.vorax reached approximately 4.6 metres (15 ft) in length, if a head to body ratio similar to Liopleurodon is applied.[4][5] However, large specimens of S.keileni from France suggest some individuals grew more than 6 metres (20 ft) long.[6]

Palaeobiology

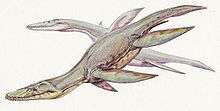

Like most Pliosaurs, Simolestes possessed salt secreting glands, which would have enabled the animal to maintain salt balance and drink seawater.[4] Recent studies on Plesiosaur locomotion indicate that Simolestes, like other Plesiosaurs, possessed a unique bauplan for movement, which differs from modern organisms in similar niches.[7]

Feeding habits

It is unclear exactly on Simolestes' feeding habits. The current consensus, however, is that the genus was primarily teuthophagus, consuming belemnites, soft teuthoids and ammonites. It is possible Simolestes was also ecologically separated from other contemporary pliosaur genera such as Liopleurodon and Pachycostasaurus by hunting in deeper waters or at night, as modern cephalopods exhibit diurnal feeding cycles, spending daylight in deeper, safer waters, and rising at night to feed.[4]

Classification

The cladogram below follows a 2011 analysis by paleontologists Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson, and reduced to genera only.[8]

| Pliosauroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Smith, Adam S.; Dyke, Gareth J. (2008). "The skull of the giant predatory pliosaur Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni: Implications for plesiosaur phylogenetics". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (10): 975–80. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..975S. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0402-z. PMID 18523747.

- GODEFROIT, P. (1994). Simolestes keileni sp. nov., un Pliosaure (Plesiosauria, Reptilia) du Bajocien supérieur de Lorraine (France). Bulletin des Académie et Société Lorraines des sciences, ISSN 0567-6576, 1994, tome 33, n°2, p. 77-95. 33. .

- R. Lydekker. 1877. Notices of new and other Vertebrata from Indian Tertiary and Secondary rocks. Records of the Geological Survey of India 10(1):30-43

- Noè, L. F. (2001). A taxonomic and functional study of the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) Pliosauroidea (Reptilia, Sauropterygia). Chicago

- Noe, Leslie F.; Jeff Liston; Mark Evans (2003). "The first relatively complete exoccipital-opisthotic from the braincase of the Callovian pliosaur, Liopleurodon" (PDF). Geological Magazine. 140 (4): 479–486. Bibcode:2003GeoM..140..479N. doi:10.1017/S0016756803007829.

- Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg. Palaeontological collections National Museum of Natural History Luxembourg. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/vbuvyu accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-06-04. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1663273715

- Muscutt, Luke & Dyke, Gareth & Weymouth, Gabriel & Naish, Darren & Palmer, Colin & Ganapathisubramani, Bharathram. (2017). The four-flipper swimming method of plesiosaurs enabled efficient and effective locomotion. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284. 20170951. 10.1098/rspb.2017.0951.

- Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01083.x (inactive 2020-01-22).CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Schumacher, Bruce A.; Carpenter, Kenneth; Everhart, Michael J. (2013). "A new Cretaceous Pliosaurid (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Carlile Shale (middle Turonian) of Russell County, Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (3): 613. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.722576.