Polycotylus

Polycotylus is a genus of plesiosaur within the family Polycotylidae.[1] The type species is P. latippinis and was named by American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1869. Eleven other species have been identified. The name means 'much-cupped vertebrae', referring to the shape of the vertebrae. It lived in the Western Interior Seaway of North America toward the end of the Cretaceous. One fossil preserves an adult with a single large fetus inside of it, indicating that Polycotylus gave live birth, an unusual adaptation among reptiles.

| Polycotylus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photograph of a paddle of Polycotylus latipinnis (1903). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Polycotylidae |

| Subfamily: | †Polycotylinae |

| Genus: | †Polycotylus Cope, 1869 |

| Type species | |

| †Polycotylus latipinnis Cope, 1869 | |

| Species | |

| |

History

Edward Drinker Cope named Polycotylus from the Niobrara Formation in Kansas in 1869. The holotype bones from which he based his description were fragmentary, representing only a small portion of the skeleton. A more complete skeleton was later found in Kansas and was described in 1906. A nearly complete skeleton was found in 1949 from the Mooreville Chalk Formation in Alabama, but was not described until 2002. A new species, P. sopozkoi, from Russia was described in 2016.[2]

Description

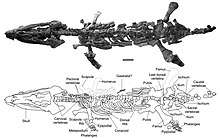

Like all plesiosaurs, Polycotylus was a large marine reptile with a short tail, large flippers, and a broad body. It has a short neck and a long head, and was about 5 metres (16 ft) long.[3] It has more neck vertebrae than other polycotylids, however. Polycotylus is thought to be a basal polycotylid because it has more vertebrae in its neck (a feature that links it with long-necked ancestors) and its humerus has a more primitive shape. The long ischia of the pelvis are a distinguishing feature of Polycotylus, as are thick teeth with striations on their surfaces, a narrow pterygoid bone on the palate and a low sagittal crest on top of the skull.[4]

Classification

Unlike some better-known long-necked plesiosaurs like Plesiosaurus and Elasmosaurus, Polycotylus had a short neck. This led to it being classified as a pliosaur, a marine reptile within the superfamily Pliosauroidea, closely related to true plesiosaurs (which belong to the superfamily Plesiosauroidea). Polycotylus and other polycotylids superficially resemble pliosaurs like Liopleurodon and Peloneustes because they have short necks, large heads, and other proportions that differ from true plesiosaurs.[4]

As phylogenetic analyses became common in the last few decades, the classification of Polycotylus and other plesiosaurs have been revised. In 1997, it and other polycotylids were reassigned as close relatives of long-necked elasmosaurids. In a 2001 study, Polycotylus was classified as a derived cryptocleidoid plesiosaur closely related to Jurassic plesiosaurs like Cryptocleidus. Below is a cladogram from a 2004 study which supported a similar classification:[4]

| Plesiosauroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2007, Polycotylus was placed in a new subfamily of polycotylids called Polycotylinae. Another newly described polycotylid called Eopolycotylus from Glen Canyon, Utah, was found to be the closest relative of Polycotylus. Below is a cladogram from the 2007 study:[5]

| Plesiosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reproduction

A fossil of P. latippinis catalogued LACM 129639 includes an adult individual with a single fetus inside it. LACM 129639 was found in Kansas during the 1980s and was in storage at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County until it was described in 2011. The length of the fetus is around 40 percent of the length of the mother. Gestation was probably two thirds complete based on what is known of the fetal development of related nothosaurs.[6] This fossil suggests that Polycotylus was viviparous, giving live birth (as opposed to laying eggs).

Viviparity, or live birth, may have been the most common form of reproduction in plesiosaurs, as they would have had difficulty laying eggs on land. Their bodies are not adapted to movement on land, and paleontologists have long hypothesized that they must have given birth in water. Other marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs also gave live birth, but LACM 129639 was the first direct evidence of vivipary in plesiosaurs. The lives of Polycotylus and other plesiosaurs were K-selected, meaning that few offspring were born to each individual but those that were born were cared for as they mature. Because it gave birth to a single large offspring, the mother Polycotylus probably gave it some form of parental care for it to survive. F. Robin O'Keefe, one of the describers of LACM 129639, suggested that the social lives of plesiosaurs were "more similar to those of modern dolphins than other reptiles."[7] K-selected life-history strategies are also seen in mammals and some lizards, but are unusual among reptiles.[8]

Examination of the fetus of Polycotylus indicates that while in the womb, plesiosaurs sacrificed fetal bone strength for accelerated growth rates. Histological analysis and comparisons with another plesiosaur, Dolichorhynchops, showed that some plesiosaur infantss were up to forty percent the length of the mother when born, and that infant plesiosaurs may have had some compromised swimming abilities.[9][10]

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2008-11-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- V.M. Efimov; I.A. Meleshin; A.V. Nikiforov (2016). "A New Species of the Plesiosaur Genus Polycotylus from the Upper Cretaceous of the Southern Urals". Paleontological Journal. 50 (5): 494–503. doi:10.1134/S0031030116050051.

- "Fossil 'suggests plesiosaurs did not lay eggs'". BBC News. 11 August 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- O'Keefe, F.R. (2004). "On the cranial anatomy of the polycotylid plesiosaurs, including new material of Polycotylus latipinnis, Cope, from Alabama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 326–34. doi:10.1671/1944.

- Albright, L.B. III; Gillette, D.D.; Titus, A.L. (2007). "Plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) Tropic Shale of southern Utah, Part 2: Polycotylidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[41:PFTUCC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Drake, N. (11 August 2011). "Sea monsters made great mothers". ScienceNews. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- "Fossilized Pregnant Plesiosaur: 78-Million-Year-Old Fossils of Adult and Its Embryo Provide First Evidence of Live Birth". ScienceDaily. 11 August 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- O'Keefe, F.R.; Chiappe, L.M. (2011). "Viviparity and K-selected life history in a Mesozoic marine plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia)". Science. 333 (6044): 870–873. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..870O. doi:10.1126/science.1205689. PMID 21836013.

- "Pregnant Plesiosaurs and Baby Bones: Bone histology reveals ontogeny in polycotylid plesiosaurs". 2019-01-17.

- o'Keefe, F. R.; Sander, P. M.; Wintrich, T.; Werning, S. (2019). "Ontogeny of Polycotylid Long Bone Microanatomy and Histology". Integrative Organismal Biology. 1. doi:10.1093/iob/oby007.