Brancasaurus

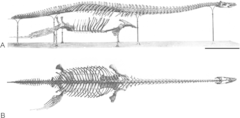

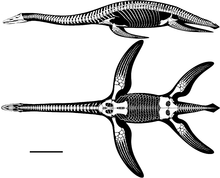

Brancasaurus (meaning "Branca's lizard") is a genus of plesiosaur which lived in a freshwater lake in the Early Cretaceous of what is now North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a long neck possessing vertebrae bearing distinctively-shaped "shark fin"-shaped neural spines, and a relatively small and pointed head, Brancasaurus is superficially similar to Elasmosaurus, albeit smaller in size at 3.26 metres (10.7 ft) in length.

| Brancasaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

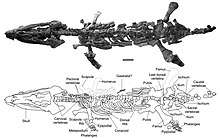

| Holotype specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Genus: | †Brancasaurus Wegner, 1914 |

| Species: | †B. brancai |

| Binomial name | |

| †Brancasaurus brancai Wegner, 1914 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The type species of this genus is Brancasaurus brancai, first named by Theodor Wegner in 1914 in honor of German paleontologist Wilhelm von Branca. Another plesiosaur named from the same region, Gronausaurus wegneri, most likely represents a synonym of this genus. While traditionally considered as a basal member of the Elasmosauridae, Brancasaurus has more recently been recovered as a member, or close relative, of the Leptocleididae, a group containing many other freshwater plesiosaurs.

Description

Brancasaurus was a medium-sized plesiosaur, at 3.26 metres (10.7 ft) in length; the holotype specimen is likely a subadult, judging by the unfused sutures in the vertebrae as well as the development of processes on the limbs and pubis.[1]

Skull

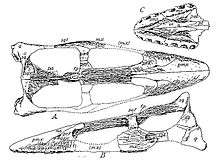

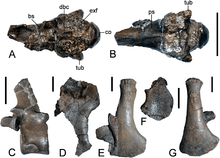

The skull of the holotype, which measures 23.7 centimetres (9.3 in) long, is long and narrow, with a tapered snout that slopes downwards at an angle of 15°. The eye sockets were roughly the same size as the temporal openings immediately behind them. A narrow, rounded ridge along the middle of the top surface of the skull extends from near the front of the premaxilla to the back of the eye sockets. The frontal bones form a rectangular bar that separates the eye sockets down the middle. A ridge running across the bar intersects with the forward-extending ridge to produce a dagger-shaped protrusion. The jugal bone, which extends from the bottom of the eye socket back to the level of the temporal openings, is entirely bordered on its bottom by the maxilla. The squamosal bones arch around to form the curved back of the skull, and bear a ridge on top for attachment of neck muscles. There is also a ridge at the point where the two bones fuse. A cast of the braincase shows impressions of the semicircular canals and membranous inner ear, as well as canals of the hypoglossal, accessory, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves, which can also be observed on the bony exoccipital-opisthotic of the braincase. On the imperfectly-preserved lower jaw, the coronoid eminence seems to be relatively low, judging by the narrow and slightly curved top edge of the surangular bone. While the teeth have been lost, they were initially described as long, slender, and awl-shaped, with rough ridges on the outer surfaces. Although it has been suggested that Brancasaurus had very reduced tooth sockets in the premaxilla, as in Leptocleidus,[2] this is impossible to verify because of damage to this portion of the skull.[1]

Vertebral column

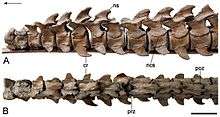

The entire neck bears 37 cervical vertebrae, and is approximately 1.18 metres (3 ft 10 in) long. The centra of the vertebrae are wider than they are tall or long. Both ends of each vertebra are slightly concave, meaning that the vertebrae are amphicoelous. The sides of the vertebrae are likewise weakly concave; unlike many other long-necked plesiosaurs, they did not bear a ridge on the side (although this may be affected by age). The neural spines of the vertebrae are distinctively shaped like shark fins, being high and triangular. There are three pectoral vertebrae at the neck-body transition, which are weakly concave, taller than they are long, and have rectangular-shaped neural spines that are directed slightly backwards. The cervical and pectoral vertebrae have deep indentations through which the notochord passed.[1]

The 19 dorsal vertebrae are similar to the pectoral vertebrae, being weakly concave and taller than long, but the neural spines are proportionally taller than the centra. The single-headed dorsal ribs are rounded but slightly flattened in cross-section, and some have a prong-like projection at the top end; their articular surfaces are slightly concave. Underneath, there are at least ten pairs of gastralia, each of which tapers to the sides and has a central groove on the bottom surface. The three sacral vertebrae are similar, but have much smaller, blunter, more oval-shaped ribs. The comparatively smaller first sacral rib is directed further outwards and backwards than the other two ribs. There initially were 25 caudal vertebrae preserved, with 22 still being accounted for. The last several caudal vertebrae are partially fused into a pygostyle-like structure. The preserved caudal ribs are flattened, triangular, and taper towards the tip of the tail.[1]

Limbs and limb girdles

The interclavicle is a large plate with a smooth upper surface and a prominent groove on the bottom surface. It also bears a small, pointed projection at its back end. The scapulae have prominent shelves on each side (diagnostic of leptocleidids and polycotylids, but not strongly differentiated in elasmosaurids), and their glenoids are clearly concave, with roughened attachments for cartilage. The two coracoids curve outwards in the middle and contact at their ends, forming a hole in the middle, although the exact morphology of this hole is uncertain. The regions where the coracoids contact is vaulted and thickened to form a weak, ridge-like projection, comparable to but probably convergently acquired from elasmosaurids. The pubes form a somewhat rectangular dish, with a convex front edge and concave outer edge, while the ischia are flat, triangular, and plate-like. The edges of the pubes where they meet the ischia curve inwards from the midline to each side. The corresponding edges of the ischia are similarly-shaped, with the curved edges of the bones collectively forming two rounded fenestrae that are connected in the center by a small rhombus-shaped opening, as also seen in Futabasaurus.[3] The ilia are rod-shaped and bent, with blunt projections halfway along their outer rims; at the top end, they are flattened into a fan-like shape.[1]

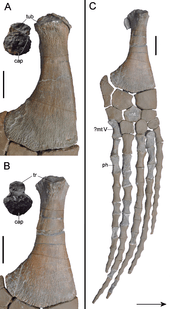

The humeri, which have a length of about 24 centimetres (9.4 in), are oval in cross-section, and about half as wide as they are long at the widest point. Their leading edges are curved in an S-shape, a trait also seen in Leptocleidus, Hastanectes, polycotylids, and the elasmosaurid Wapuskanectes, but not in Nichollssaura.[2][4] The only femur that is presently available is 21.5 centimetres (8.5 in) long; it is concave on one edge, whereas the other edge is straight near the top but curves sharply near the bottom. The rest of the long bones of the limb have been lost. Allegedly, the radius was similar to but smaller and straighter than the tibia, and there was a hole present between the tibia and fibula. The 14 preserved phalanges, which likely include elements from both the forelimbs and the hindlimbs, are long and hourglass-shaped.[1]

Possible soft tissue

Soft tissue was apparently preserved with the specimen, but was subsequently removed during preparation. Covering the limbs and the rest of the body was a layer of smooth, multilayered calcite, which was originally interpreted as preservation of decaying skin. Additionally, an accumulation of sediment in the abdominal region may have represented gut contents, with both gastroliths and digested bones. However, since both samples of the alleged soft tissue are no longer available, it is impossible to verify these interpretations.[1]

Discovery and naming

The holotype specimen of Brancasaurus brancai is GPMM A3.B4, stored at the University of Münster. It originates from a clay pit near the city of Gronau, North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany. The specimen was discovered in July 1910 by workers in the clay pit, who dug it out using pickaxes; in doing so, they damaged the specimen (in particular, the pubis had been broken into 176 pieces), and left behind a number of small fragments that were later personally collected by paleontologist Theodor Wegner, who in 1928 described the specimen in detail. The skeleton is fairly complete, consisting of various parts of the skull, most of the vertebrae, several isolated ribs and gastralia, parts of the pectoral and pelvic girdles, both humeri, one femur, and various foot bones from the flippers. Over time, a number of parts have been lost, including several pieces of the skull, teeth, gastralia and caudal vertebrae, a second femur, and a radius, tibia, and fibula. A wax endocast of the brain of the type specimen is stored as SMF R4076 in the Naturmuseum Senckenberg.[1]

The clay pit from which the type specimen originates is part of the Isterberg Formation in the Bückeberg Group,[5] also known in the past as the "German Wealden facies".[6] The Bückeberg Group, which is divided into six zones,[7] belongs to the Berriasian of the Cretaceous, with the boundary between the Berriasian and the Valanginian being at the top of the group.[8] The parts of the Isterberg Formation exposed at Gronau belong to the zones "Wealden 5" and "Wealden 6", which correspond to the uppermost-Berriasian. A second, more fragmentary subadult individual, GZG.BA.0079, consists of the pubis, ischium, and several vertebral components; it originates from the slightly lower Deister Formation ("Wealden 3"[7]) in the Bückeberg Group, and can only be referred to Brancasaurus sp., since it is relatively incomplete and differs in several minor vertebral characteristics from the type of B. brancai. Other probable but isolated Brancasaurus elements come from outcrops of the Isterberg and Fuhse Formations in Lower Saxony; the latter formation is also in the Bückeberg Group.[1]

Synonyms

The specimen GPMM A3.B2 consists of teeth, parts of the jaws, the braincase and other fragmentary parts of the skull, vertebrae, pieces of ribs, part of the pectoral girdle, the entire pelvic girdle, one complete and one partial humerus, an ulna, two femora, a fibula, and various foot bones. While this specimen was originally assigned to Brancasaurus, Hampe (2013) referred it to a new genus and species, Gronausaurus wegneri.[9] It was discovered some 8 metres (26 ft) higher in the stratigraphic column than the type specimen of Brancasaurus. Later analysis found that this specimen, which was mature, was virtually indistinguishable from the type of Brancasaurus with the exception of the length of the ischium, the height of the cervical neural spines, the width of the cervical centra, and whether the dorsal neural spines are constricted at their base. These minor differences can probably be attributed to either individual-based or age-based variation, supporting G. wegneri as a junior synonym of B. brancai.[1]

E. Koken named Plesiosaurus limnophilus in 1887 based on isolated cervical vertebrae from outcrops of the Bückeberg Group in Lower Saxony. From the same locality, Koken subsequently named two further species of Plesiosaurus, P. degenhardti and P. kanzleri, and also referred some material to P. valdensis. All of this material is not particularly diagnostic, and has been partially lost; thus, they have been considered nomina dubia. Sachs et al. considered all of these to represent remains of Brancasaurus, with the exception of P. degenhardti, which was retained as a nomen dubium on account of lacking the distinctive cervical neural spines of Brancasaurus.[1]

Classification

Initially, Brancasaurus was assigned to the Elasmosauridae by Wegner. He noted, however, that it had a shorter neck and a narrower head, as well as various distinctive morphologies of the skull roof, teeth, and vertebrae (especially the "shark fin"-shaped neural spines of the cervical vertebrae) compared to other members of the group known at the time. A number of subsequent studies have considered Brancasaurus as a basal member of the Elasmosauridae,[10][11][12][13] with some even using Brancasaurus to define the clade.[11] Nevertheless, a number of contrary taxonomic opinions have been expressed; in particular, Theodore E. White created a new family, Brancasauridae, to contain Brancasaurus, Seeleyosaurus, and "Thaumatosaurus", a defunct genus with species now belonging to Rhomaleosaurus and Meyerasaurus.[14][1]

An alternative phylogenetic hypothesis that has gained substantial traction places Brancasaurus in the clade Leptocleididae,[15][2][16] along with other leptocleidids including Leptocleidus itself, Vectocleidus, Umoonasaurus, Nichollssaura, and also possibly Hastanectes.[16] This result has been recovered by the phylogenies of Benson et al., who have also noted a number of morphological traits which ally Brancasaurus with the more general Leptocleidia.[2][1]

A 2016 phylogenetic analysis conducted by Sachs et al. found two equally strong alternative placements of Brancasaurus (including Gronausaurus): within the Leptocleididae; or as the sister taxon of a clade containing both Leptocleididae and Polycotylidae, with the clade containing all of the aforementioned taxa being the sister taxon of Elasmosauridae. The study concluded that, currently, no phylogenetic dataset is sufficient to resolve the relationships of Brancasaurus. In addition to the fact that the type specimen is a subadult, this inconsistency in results can be attributed to the mix of leptocleidid, polycotylid, and elasmosaurid characteristics that is seen in Brancasaurus.[16] The cladograms below illustrate the alternate arrangements.[1]

|

Topology A: Brancasaurus in the Leptocleididae, based on Benson et al. (2013)[2]

|

Topology B: Brancasaurus outside Leptocleididae, based on Benson & Druckenmiller (2014)[16]

|

|

Paleoecology

The Bückeberg Group, from which Brancasaurus originates, likely represented a large, continental freshwater lake that the surrounding uplands drained into. In turn, the lake itself was temporarily connected to the Boreal Sea via a passage to the west. During the time at which the layers of "Wealden 5" and "Wealden 6" were deposited, the lake expanded and became more brackish as a result of marine transgression.[17] The deposited sediments probably represent the oxygen-poor bottom portion of the lake, with the plesiosaurs of the Bückeberg Group being presumably preserved after they sank through the water column to the bottom.[1]

Asides from Brancasaurus, other constituents of the Bückeberg Group are benthic invertebrates, including neomiodontid bivalves;[1] hybodont sharks, including Hybodus, Egertonodus, Lonchidion, and Lissodus; the actinopterygian fish Caturus, Lepidotes, Coelodus, Sphaerodus, Ionoscopus, and Callopterus,[9] which Brancasaurus would have preyed on in surface waters;[18] the turtle Desmemys;[9] crocodilians, including Goniopholis, Pholidosaurus, and Theriosuchus; the theropod Altispinax; the marginocephalian Stenopelix; and an ankylosaur referred to Hylaeosaurus.[19][20] Other indeterminate remains have been assigned to pterosaurs; the crocodilian clades Hylaeochampsidae and Eusuchia; and the dinosaurian clades Dryosauridae, Ankylopollexia, Troodontidae, and Macronaria.[20]

References

- Sachs, S.; Hornung, J.J.; Kear, B.P. (2016). "Reappraisal of Europe's most complete Early Cretaceous plesiosaurian: Brancasaurus brancai Wegner, 1914 from the "Wealden facies" of Germany". PeerJ. 4: e2813. doi:10.7717/peerj.2813. PMC 5183163. PMID 28028478.

- Benson, R.B.J.; Ketchum, H.F.; Naish, D.; Turner, L.E. (2013). "A new leptocleidid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Vectis Formation (Early Barremian–early Aptian; Early Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight and the evolution of Leptocleididae, a controversial clade". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (2): 233–250. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.634444. S2CID 18562271.

- Sato, Tamaki; Hasegawa, Y.; Manabe, M. (2006). "A new elasmosaurid plesiosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Fukushima, Japan". Palaeontology. 49 (3): 467–484. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00554.x.

- Albright, L.B.; Gillette, D.D.; Titus, A.L. (2007). "Plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian–Turonian) Tropic Shale of Southern Utah, part 2: Polycotylidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[41:pftucc]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524666.

- Casey, R.; Allen, P.; Dörhöfer, G.; Gramann, F.; Hughes, N. F.; Kemper, E.; Rawson, P. F.; Surlyk, F. (1975). "Stratigraphical subdivision of the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary beds in NW Germany". Newsletters on Stratigraphy. 4 (1): 4–5. doi:10.1127/nos/4/1975/4.

- Allen, P. (1955). "Age of the Wealden in North-Western Europe". Geological Magazine. 92 (4): 265–281. Bibcode:1955GeoM...92..265A. doi:10.1017/S0016756800064311.

- Elstner, F.; Mutterlose, J. (1996). "The Lower Cretaceous (Berriasian and Valanginian) in NW Germany". Cretaceous Research. 17 (1): 119–133. doi:10.1006/cres.1996.0010.

- Mutterlose, J.; Bodin, S.; Fahnrich, L. (2014). "Strontium-isotope stratigraphy of the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian–Barremian): Implications for Boreal–Tethys correlation and paleoclimate". Cretaceous Research. 50 (4): 252–263. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.03.027.

- Hampe, O. (2013). "The forgotten remains of a leptocleidid plesiosaur (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauroidea) from the Early Cretaceous of Gronau (Münsterland, Westphalia, Germany)". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 78 (4): 473–491. doi:10.1007/s12542-013-0175-3.

- Brown, D.S. (1981). "The English Upper Jurassic Plesiosauroidea (Reptilia) and a review of the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria". Bulletin of the British Museum. 35: 253–347.

- O'Keefe, F.R. (2001). "A Cladistic Analysis and Taxonomic Revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia)". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 213: 1–63.

- O'Keefe, F.R. (2004). "Preliminary description and phylogenetic position of a new plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Toarcian of Holzmaden, Germany". Journal of Paleontology. 78 (5): 973–988. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0973:PDAPPO>2.0.CO;2.

- Großman, F. (2007). "The taxonomic and phylogenetic position of the Plesiosauroidea from the Lower Jurassic Posidonia Shale of south-west Germany". Palaeontology. 50 (3): 545–564. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00654.x.

- White, T.E. (1940). "Holotype of Plesiosaurus longirostris Blake and Classification of the Plesiosaurs". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (5): 451–467. JSTOR 1298550.

- Ketchum, H.F.; Benson, R.B.J. (2010). "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role of taxon sampling in determining the outcome of phylogenetic analyses". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 361–392. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00107.x. PMID 20002391.

- Benson, R.B.J.; Druckenmiller, P.S. (2014). "Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition". Biological Reviews. 89 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/brv.12038. PMID 23581455.

- Mutterlose, J.; Bornemann, A. (2000). "Distribution and facies patterns of Lower Cretaceous sediments in northern Germany: a review". Cretaceous Research. 21 (6): 733–759. doi:10.1006/cres.2000.0232.

- Halstead, L.B. (1989). "Plesiosaur locomotion". Journal of the Geological Society. 146 (1): 37–40. Bibcode:1989JGSoc.146...37H. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.146.1.0037.

- Sachs, S.; Hornung, J.J. (2013). "Ankylosaur Remains from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian) of Northwestern Germany". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60571. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860571S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060571. PMC 3616133. PMID 23560099.

- Hornung, J.J. (2013). Contributions to the Palaeobiology of the Archosaurs (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Bückeberg Formation ('Northwest German Wealden'– Berriasian-Valanginian, Lower Cretaceous) of northern Germany (Dr. rer. nat.). Georg-August University School of Science. pp. 318–351.

External links

- Brancasaurus in the Plesiosaur Directory