Youth vote in the United States

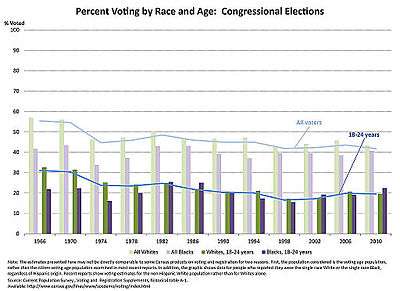

The youth vote in the United States is the cohort of 18–24 year-olds as a voting demographic.[1] Many policy areas specifically affect the youth of the United States, such as education issues and the juvenile justice system.[2] The general trend in voter turnout for American elections has been decreasing for all age groups, but "young people's participation has taken the biggest nosedive".[3] This low youth turnout is part of the generational trend of voting activity. Young people have the lowest turnout, though as the individual ages, turnout increases to a peak at the age of 50 and then falls again.[4] Ever since 18-year-olds were given the right to vote in 1972, youth have been under represented at the polls.[1] In 1976, one of the first elections in which 18-year-olds were able to vote, 18–24 year-olds made up 18 percent of all eligible voters in America, but only 13 percent actually voted – an under-representation of one-third.[1] In the next election in 1978, youth were under-represented by 50 percent. "Seven out of ten young people…did not vote in the 1996 presidential election… 20 percent below the general turnout."[5] In 1998, out of the 13 percent of eligible youth voters in America, only five percent voted.[1] During the competitive presidential race of 2000, 36 percent of youth turned out to vote and in 2004, the "banner year in the history of youth voting," 47 percent of the American youth voted.[3] Recently, in the 2008 U.S. presidential election, the number of youth voters tripled and even quadrupled in some states compared to the 2004 elections.[6] In 2008, Barack Obama spoke about the contributions of young people to his election campaign outside of just voter turnout.[7]

History of the Youth Vote

Initially, the framers of the U.S. Constitution and state voting laws were skeptical of the role of young people in American politics. States uniformly set 21 as the voting age, although Connecticut debated lowering it to 18 in 1819. In general, young Americans were expected to be deferential to their elders, and John Adams famously cautioned that expanding suffrage would encourage “lads from twelve to twenty-one” to demand the right to vote. [8]

Yet as the suffrage expanded to non-property-holders in the early 1800s, young people came to play a larger role in politics. During the rise of Jacksonian Democracy, youths often organized Young Men’s clubs in support of the Democratic, National Republican, Whig, or Anti-Masonic parties. [9] Presidential campaigns often organized torch-lit rallies of thousands of marchers, and analyses of these club rosters show that members were often in their late teens and early twenties. [10] The demands of popular democracy – which often drew voter turnouts above 80% of eligible voters – led political machines to rely on youths as cheap, enthusiastic campaigners for political machines. In 1848, Abraham Lincoln suggested that the Whig Party in Springfield, Illinois, make use of “the shrewd, wild boys about town, whether just of age or a little under age.” [11]

In the mid-to-late 1800s, young men enthusiastically cast their “virgin vote” when turning 21. Voting was often seen as a rite of passage and public declaration of manhood, adulthood, and citizenship. Young African-Americans participated in voting and campaigning where they could vote, and young women, though prevented from voting themselves, followed politics closely, read partisan newspapers, and argued politics with the young men in their lives. [12]

Around the turn of the 20th century, political reformers reduced party’s reliance on young activists in an effort to clean up politics. Youth turnout fell shortly thereafter, especially among first time “virgin voters,” whose turnout declined 53% between 1888 and 1924. [13] As turnout fell in the early 20th century, young people played less role in campaigning. Though individual campaigns, like those of Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932, and John F. Kennedy in 1960, specifically appealed to youth, political parties generally showed less systematic interest in the youth vote.

Sustained interest in lowering the voting age began during World War II when Congress passed legislation allowing young men to be drafted at the age of eighteen. While a few individual states began to allow 18-year-old voting before the Civil Rights Extension Act of 1970 and 26th Amendment (1971) lowered the voting age to eighteen, efforts to lower the voting age generally garnered little support.[14]

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, young people had shown themselves to be vital political actors and were demanding more of a role in American public life. The qualities associated with youth – young people's idealism, lack of "vested interests," and openness to new ideas – came to be seen as positive qualities for a political system that seemed to be in crisis. Rising high school graduation rates and young people's increasing access to political information also spurred re-evaluations of 18-year-olds' fitness for voting rights. In addition, Civil Rights organizations, the National Education Association, and youth-centered groups formed coalitions that coordinated lobbying and grassroots efforts aimed at lowering the voting age on both the state and national level.[14]

After the passage of the 26th Amendment, voter turnout among 18–24 year olds fell throughout the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, although there seems to have been a resurgence in the last generation.

Variables affecting the youth vote in the United States

The lack of youth participation in the voting process is not a random phenomenon. There are multiple variables that have an influence on the voting behaviors of youth in the United States.

Voting process

The voting process has two steps. An eligible voter – a U.S. citizen over the age of 18[15] – must first register to vote and then commit the act of voting. The voting process is regulated by each state individually and therefore varies from state to state.[16] The process of registering to vote is different depending on the state.[16] Pre-registration is available to youth under the age of 18 in 20 states and Washington D.C.[17] Potential voters may also register on Election Day – or on the day on which they vote early – in 10 states and Washington D.C.[18] This may be done at the polling place or at an election official's office.[18] Residents of the 40 states which do not allow same day registration require potential voters to register by a deadline, typically from eight to 30 days out from the election.[18] Over half of the states in the U.S. offer some sort or online voter registration.[19] This consists of the same process as a paper registration form, only it is digital and sent to election officials to review over the web. This process was first introduced in Arizona in 2002.[19] There are different regulations on the time and avenue through which a citizen can vote. Early voting is available in 33 states and Washington D.C. This must be done in person at a designated polling place. Early voting period lengths vary from state to state.[20] If a potential voter is not able to vote in person on Election Day or during the early voting period, they may request an absentee ballot. In 20 states, an excuse must be filed to receive the absentee ballot.[20] In 27 states and Washington D.C., a voter may acquire an absentee ballot without an excuse. In Washington, Oregon and Colorado, all voting is done through the mail. A ballot is mailed to the voters residence and after the voter fills it out, he/she may mail it back. No in person polls are conducted.[20] Otherwise, the typical voting period is twelve hours on a weekday at which time voters must go to the polls in person and cast their votes.

Two party system

The winner-take-all system in the United States limits the success of third party candidates who may have a difficult time achieving an electoral majority.[5] Young people are increasingly supporting third party candidates, though the American political system has continued to foster a two-party system. In 1992, Ross Perot, a third party candidate for president, won 22 percent of the 18–24 year-old vote, his strongest performance among any demographic group.[5] These third party candidates who gain such support from the youth of the U.S. do not benefit from major party coffers – they must campaign by themselves.

Money in politics

In nine out of ten elections, the candidate who spends the most money is elected.[5] The average cost of a successful campaign for the United States House of Representatives is nearly half a million dollars.[5] A large portion of this money comes from "large individual contributions" – an average of 74 percent of the campaign funds raised in the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney were large individual contributions. An average of 25 percent of presidential campaign funds in 2012 were made in "small individual contributions."[21] The Supreme Court rulings on Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission in 2010 and SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission allowed corporations and individuals to donate directly to political action committees (PACs), Super PACs, or 501(c)(4)s which could then spend unlimited amounts of money on campaigns of their own.[22] The general perception of this system is that in turn for such large donations, candidates will vote in accordance to their large donors to ensure future donations during their reelection bid and pay the smaller donors slight attention.[5] When the media reports that on campaign finance scandals, it is portrayed as a solitary incident with no connection to later policy outcomes.[5] Americans have become so accustomed to the power of money in politics they are not surprised when a scandal occurs.[5] The future for the influence of large donors is unlikely to change because the lawmakers with the power to create and pass campaign finance reform are those who benefit most from the large donations when their term is up and they must run reelection campaigns.[5]

Frequent change of residence

Between the ages of 18 and 24, youth have the potential to graduate high school, move away to college and change residences multiple times as they begin their career. As youth change residences often, the local issues and elections relevant to the area may not affect the youth yet or be significant and change from residence to residence.[5] College students face the decision whether to stay registered in their hometowns or to register in the community in which they will reside.[5] The fewer federal tax obligations that apply to youth ages 18–24 only loosely tie them to the government and policy making decisions and do not entice youth to vote and make a change.[5]

Lack of candidate contact

Young people complain that those in politics do not communicate with them.[5] Political candidates and their campaigns know, through past election data, that youth are not a reliable voting group and choose to spend their campaign dollars on those who are more likely to turn out to vote. For this reason, candidates tend to focus on issues that pertain to their targeted voters to gain their support, further discouraging youth voters. The discouraged youth complete the cycle of neglect by not turning out to vote, proving to candidates that the youth are not a reliable voting group.[3] "Elected officials respond to the preferences of voters, not non-voters," therefore ignoring the youth of America who do not turn out to vote.[1]

Volunteering efforts

Though many consider voting a civic activity, youth today seem to have separated the political from the civic.[3] Youth often participate in volunteer opportunities, fundraisers and other activist activities. In this way, youth can make a difference in their communities and are able to see change immediately when seeing the larger picture of a movement, including the political aspect, may be more difficult or intangible.[5]

Efforts to encourage youth vote

Organizations

A variety of organizations worked to encourage young people to vote.[23] By 2018, Rock the Vote, a platform used by grassroots campaigns,[3][5][23] had registered over 7 million votes and gained over 350 partners directing people to its online registration tool.[24]

Another organization working on registering young voters nationwide is The Civics Center, a sister organization of Rock the Vote. It has launched a campaign that engages with over 1,000 schools nationwide.

Efforts before the 1970s include:

Later efforts include:

- 18 in '08

- 18by.Vote

- Bus Federation Civic Fund

- Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE)

- College Republicans and College Democrats of America all over country

- Declare Yourself[3]

- HeadCount, picked by the Ad Council in 2018 for a spot to be seen by 10 million

- Hip Hop Summit Action Network[3]

- Inspire U.S.[25]

- League of Young Voters

- Make It 100

- MTV[3]

- National Stonewall Democrats[3]

- New Voters Project[3]

- New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG)

- Sean Combs's "Vote or Die" campaign[3]

- Spitfire Strategies[3]

- Our Time

- TurboVote.org (with Snapchat and others)[26]

- When We All Vote, co-chaired by Michelle Obama[23]

- World Wrestling Entertainment's Smackdown Your Vote[3]

- Young Greens Caucus

- Young Voter PAC

- Young Voter's Alliance[3]

- YouthVote USA

Campaign strategies

Because the youth population is so large, many campaigns try to gain their support during elections.[3] Efforts to capture the youth vote include registration drives, outreach, and specifically youth-friendly policy platforms. An example of a fairly successful voter registration drive would be the "Reggie the Rig" drive by the Republican National Committee in the 2004 election. With a goal of registering three million new voters, the "Reggie the Rig" bus traveled to college campuses, a place to reach thousands of potential youth voters at once.[3] During the same election, the Democrats held their own campus visits, but instead of focusing on registration, the Kerry campaign spread the word about their youth policy platform called Compact with the Next Generation.[3] The Democrats also placed targeted ads on TV during shows such as Saturday Night Live and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart.[3] This targeted campaign on TV has often been supplemented with outreach through the internet in modern campaigns. New technology, especially the internet, is making it easier for candidates to reach the youth. It has been found that "young people who encounter campaign information on their own accord and spend time interacting with political material may come to see themselves interested in politics."[1]

Young adults are "over-represented among all computer and Internet users" – three fourths of Americans under the age of 18 are able to access a computer and, on average, use it for half an hour a day.[1] As the Internet and computers have become more accessible to youth, such methods have been used to seek and find information and share it on social media cites. Websites such as Facebook and YouTube not only allow youth who don't subscribe to newspapers or watch the evening news to stay on top of the polls, but also allows them to share their opinions of the polls and candidates.[27] If the use of technology were to be fully integrated into politics, the youth and adult groups would be equally active in politics.[1] Online news media, in particular, is believed to have a positive impact on young citizens due to its interactivity.[28] It not only provides them with the information they need to form their political beliefs, become more informed regarding democracy, and to gain a better understanding of current issues, but it also provides them with a platform to discuss these ideas with other individuals, not only on a more localized scale but also on a global scale.[28]

Legislation

In the United States, there has been legislation passed to help youth access the vote. The National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), often called the "motor-voter" law, passed in 1993, allows those 18 years and older to register to vote at a driver's license office or public assistance agency.[5] The law also required states to accept a uniform mail-in voter registration application.[5] Additionally, some states have extended the period in which citizens can vote instead of requiring a vote within 12 hours on a single day.[5]

Two cities in Maryland, Takoma Park and Hyattsville, allow 16 and 17-year-olds to vote in local elections.[29]

See also

- Youth politics

- Youth suffrage

- Young Voters for the President

- Apathy is Boring, a Canadian non-profit and non-partisan organization that promotes youth involvement in politics

Further reading

- John B. Holbein and D. Sunshine Hillygus. 2020. Making Young Voters: Converting Civic Attitudes into Civic Action. Cambridge University Press.

- Grinspan, Jon. (2016) The Virgin Vote: How Young Americans Made Democracy Social, Politics Personal, and Voting Popular in the Nineteenth Century. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press).

References

- Iyengar, Shanto; Jackman, Simon (November 2003). "Technology and Politics: Incentives for Youth Participation". International Conference on Civic Education Research: 1–20.

- Sherman, Robert (Spring 2004). "The Promise of Youth is in the Present". National Civic Review. 93: 50–55. doi:10.1002/ncr.41.

- Walker, Tobi (Spring 2006). ""Make Them Pay Attention to Us": Young Voters and the 2004 Election". National Civic Review. 95: 26–33. doi:10.1002/ncr.128.

- Klecka, William (1971). "Applying Political Generations to the Study of Political Behavior: A Cohort Analysis". Public Opinion Quarterly. 35 (3): 369. doi:10.1086/267921.

- Strama, Mark (Spring 1998). "Overcoming Cynicism: Youth Participation and Electoral Politics". National Civic Review. 87 (1): 71–77. doi:10.1002/ncr.87106.

- Harris, Chris. "Super Tuesday Youth Voter Turnout Triples, Quadruples in Some States." MTV News. retrieved 6 Feb 2008.

- Rankin, David. (2013). US Politics and Generation Y : Engaging the Millennials. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-62637-875-9. OCLC 1111449559.

- Adams, John, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, vol. 9, Ed. quoted in Charles Francis Adams (Boston, 1856), 378.

- Grinspan, Jon. (2016) The Virgin Vote: How Young Americans Made Democracy Social, Politics Personal, and Voting Popular in the Nineteenth Century, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press)

- Grinspan, Jon. (2009) “‘Young Men for War’: The Wide Awakes and Lincoln’s 1860 Presidential Campaign.” Journal of American History 96, 367.

- Lincoln Abraham, June 22, 1848, Abraham Lincoln: The Collected Works, Eight Volumes, Ed. Roy P. Basler, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 1: 491.

- Grinspan, Jon. (2016) The Virgin Vote.

- Kleppner, Paul. (1982), Who Voted? The Dynamics of Electoral Turnout, 1870-1980, (New York: Praeger, 1982), 68-9

- de Schweinitz, Rebecca (2015-05-22), ""The Proper Age for Suffrage"", Age in America, NYU Press, pp. 209–236, ISBN 978-1-4798-7001-1, retrieved 2020-07-29

- "Register to Vote". USA.gov. U.S. Government. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Elections and Voting". The White House. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Pre-registration for Young Voters". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Same Day Voter Registration". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Online Voter Registration". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Absentee and Early Voting". The National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Source of Funds". OpenSecrets.org. Center for Responsive Politics. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- Coates, John (November 6, 2012). "Corporate Politics, Governance, and Value Before and After Citizens United". Empirical Legal Studies. 9 (4): 657–696. doi:10.1111/j.1740-1461.2012.01265.x.

- Schwarz, Hunter. "Voter registration is so hot right now". CNN. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- "Online Voter Registration Platform". Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- "Inspire U.S".

- "Snapchat Helped Register Over 400,000 Voters". 2018-10-24.

- Von Drehle, David. "Why Young Voters Care Again." Time Magazine. Feb 2008:34-48

- Holt, Kristoffer; Shehata, Adam; Strömbäck, Jesper; Ljungberg, Elisabet (2013). "Age and the effects of news media attention and social media use on political interest and participation: Do social media function as leveller?". European Journal of Communication. 28: 19–34. doi:10.1177/0267323112465369.

External links

- Youth Vote Overseas Online registration and ballot request tools for U.S. voters 18–29 living overseas, including students, volunteers and young professionals