Steppe bison

The steppe bison or steppe wisent (Bison priscus)[1] is an extinct species of bison that was once found on the mammoth steppe where its range included British Isles[2], Europe,[3] Central Asia,[4] Northern to Northeastern Asia,[5][6][7][8] Beringia, and North America,[9][10] from northwest Canada to Mexico during the Quaternary. This wide distribution is sometimes called the Pleistocene bison belt compared to the Great bison belt [11]The radiocarbon dating of a steppe bison skeleton indicates that it was present 5,400 years ago in Alaska.[12] Three chronological subspecies, Bison priscus priscus, Bison priscus mediator, and Bison priscus gigas, have been suggested.[13]

| Steppe bison | |

|---|---|

| |

| "Blue Babe", a mummified specimen from Alaska | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Bison |

| Species: | †B. priscus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Bison priscus Bojanus, 1827 | |

Evolution

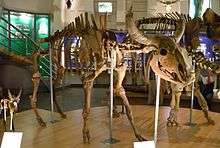

The steppe bison is believed to have evolved from Bison paleosinensis in South Asia, which means the species appeared at roughly the same time and region as the aurochs (Bos primigenius) with which its descendants are sometimes confused. The steppe bison was eventually contemporaneous with the Pleistocene woodland bison (B. schoetensacki) and the European bison (Bison bonasus) in Europe, Leptobison in Japan,[5][6] and the long-horned bison (Bison latifrons) in North America.

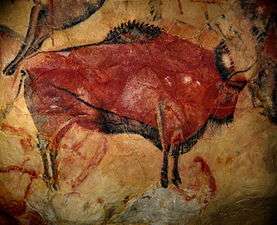

The steppe bison became extinct possibly in the middle to the late Holocene, as it was replaced in Europe by the modern European bison (B. bonasus), in 2016 thought to be a hybrid between B. priscus and the Bos primigenius,[14], a premature conclusion based on incomplete lineage sorting[15], and in America by a sequence of several species (such as Bison antiquus and Bison occidentalis) culminating in the modern American bison (Bison bison).[16] European cave paintings appear to depict both B. bonasus and B. priscus.[17]

Resembling the modern bison species, especially the American wood bison (Bison bison athabascae),[18] the steppe bison was over 2 m tall at the withers, reaching 900 kg (2,000 lb) in weight.[19] The tips of the horns were a meter apart, the horns themselves being over half a meter long.

Discoveries

Steppe bison appear in cave art, notably in the Cave of Altamira and Lascaux, and the carving Bison Licking Insect Bite, and have been found in naturally ice-preserved form.[16][20][21]

Blue Babe is the 36,000-year-old mummy of a male steppe bison which was discovered north of Fairbanks, Alaska, in July 1979.[22] The mummy was noticed by a gold miner who named the mummy Blue Babe – "Babe" for Paul Bunyan's mythical giant ox, permanently turned blue when he was buried to the horns in a blizzard (Blue Babe's own bluish cast was caused by a coating of vivianite, a blue iron phosphate covering much of the specimen).[1] Blue Babe is also frequently referenced when talking about scientists eating their own specimens: the research team that was preparing it for permanent display in the University of Alaska Museum removed a portion of the mummy's neck, stewed it, and dined on it to celebrate the accomplishment.[23][24]

In 2011, a 9,300-year-old mummy was found at Yukagir in Siberia.[25]

Deextinction attempts

A team of Russian and Korean scientists proposed potential deextinction of steppe bison with wood bison in Siberia using cloning techniques, especially with reintroduced herds in Yakutia, Russia.[26]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bison priscus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Bison priscus |

- "Steppe Bison" Archived 2010-12-12 at the Wayback Machine – Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Beringia.com. Retrieved on 2013-05-31.

- Kirkdale Cave (Pleistocene of the United Kingdom)

- Вестник Кирилло-Белозерского музея 9 (Май 2006) О. Яшина, Т.В. Цветкова – Кирилловский бизон. Kirmuseum.ru. Retrieved on 2013-05-31.

- Vasiliev, S. K. (2008). "Late pleistocene bison (Bison p. priscus Bojanis, 1827) from the Southeastern part of Western Siberia". Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 34 (2): 34–56. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2008.07.004.

- Kurosawa, Y. "モノが語る牛と人間の文化 - ② 岩手の牛たち" (PDF). LIAJ News (109): 29–31. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- Hasegawa, Y.; Okumura, Y.; Tatsukawa, H. (2009). "First record of Late Pleistocene Bison from the fissure deposits of the Kuzuu Limestone, Yamasuge,Sano-shi,Tochigi Prefecture,Japan" (PDF). Bull.Gunma Mus.Natu.Hist. (13): 47–52. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- Boeskorov, Gennady G.; Potapova, Olga R.; Protopopov, Albert V.; Plotnikov, Valery V.; Agenbroad, Larry D.; Kirikov, Konstantin S.; Pavlov, Innokenty S.; Shchelchkova, Marina V.; Belolyubskii, Innocenty N.; Tomshin, Mikhail D.; Kowalczyk, Rafal; Davydov, Sergey P.; Kolesov, Stanislav D.; Tikhonov, Alexey N.; Van Der Plicht, Johannes (2016). "The Yukagir Bison: The exterior morphology of a complete frozen mummy of the extinct steppe bison, Bison priscus from the early Holocene of northern Yakutia, Russia". Quaternary International. 406: 94–110. Bibcode:2016QuInt.406...94B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.084.

- Yeong-Seok Jo, John T. Baccus, John Koprowski, 2018, Mammals of Korea, p.30, National Institute of Biological Resources of Korea

- Zazula, Grant D.; MacKay, Glen; Andrews, Thomas D.; Shapiro, Beth; Letts, Brandon; Broc, Fiona (2009). "A late Pleistocene steppe bison (Bison priscus) partial carcass from Tsiigehtchic, Northwest Territories, Canada". Quaternary Science Reviews. 28 (25–26): 2734–2742. Bibcode:2009QSRv...28.2734Z. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.06.012.

- Marsolier-Kergoat, Marie-Claude; Palacio, Pauline; Berthonaud, Véronique; Maksud, Frédéric; Stafford, Thomas; Bégouën, Robert; Elalouf, Jean-Marc (2015-06-17). "Hunting the Extinct Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) Mitochondrial Genome in the Trois-Frères Paleolithic Painted Cave". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0128267. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128267. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4471230. PMID 26083419.

- Hunting the Extinct Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) Mitochondrial Genome in the Trois-Frères Paleolithic Painted Cave

- Zazula, Grant D.; Hall, Elizabeth; Hare, P. Gregory; Thomas, Christian; Mathewes, Rolf; La Farge, Catherine; Martel, André L.; Heintzman, Peter D.; Shapiro, Beth (2017). "A middle Holocene steppe bison and paleoenvironments from the Versleuce Meadows, Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (11): 1138–1152. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54.1138Z. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0100. hdl:1807/78639.

- Castaños, J.; Castaños, P.; Murelaga, X. (2016). "First Complete Skull of a Late Pleistocene Steppe Bison ( Bison priscus ) in the Iberian Peninsula". Ameghiniana. 53 (5): 543–551. doi:10.5710/AMGH.03.06.2016.2995.

- Soubrier, J.; Gower, G.; et al. (2016). "Early cave art and ancient DNA record the origin of European bison". Nature Communications. 7: 13158. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713158S. doi:10.1038/ncomms13158. PMC 5071849. PMID 27754477.

- Wang, Kun; Lenstra, Johannes A.; et al. (2018). "Incomplete lineage sorting rather than hybridization explains the inconsistent phylogeny of the wisent". Nature Communications Biology. 1: 13158. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0176-6.

- Verkaar, E. L. C.; Nijman, IJ; Beeke, M.; Hanekamp, E.; Lenstra, J. A. (2004). "Maternal and Paternal Lineages in Cross-Breeding Bovine Species. Has Wisent a Hybrid Origin?". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (7): 1165–70. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh064. PMID 14739241.

- Briggs, H. (19 October 2016). "Cave paintings reveal clues to mystery Ice Age beast". BBC.com. Retrieved 2016-10-19.

- Boeskorov, Gennady G.; Potapova, Olga R.; et al. (25 June 2016). "The Yukagir Bison: The exterior morphology of a complete frozen mummy of the extinct steppe bison, Bison priscus from the early Holocene of northern Yakutia, Russia". Quaternary International. 406: 94–110. Bibcode:2016QuInt.406...94B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.084.

- McPhee, R. D. E. (1999). Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences. Springer. p. 262. ISBN 978-0306460920.

- Dale Guthrie, R (1989). Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story of Blue Babe. ISBN 9780226311234.

- Paglia, C. (2004). "The Magic of Images: Word and Picture in a Media Age". Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics. 11 (3): 1–22. JSTOR 20163935.

- Deem, James M. "Blue Babe - the 36,000 year-old male bison" James M. Deem's Mummy Tombs. 1988-2012. Accessed 20 March 2012.

- Dale Guthrie, R (1989). Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story of Blue Babe. p. 298. ISBN 9780226311234.

- ḎḤWTY. "Blue Babe: Would You Eat 36,000-year-old Bison Meat?". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Palermo, Elizabeth (6 November 2014). "9,000-Year-Old Bison Mummy Found Frozen in Time". www.livescience.com. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Cloning ancient extinct bison sounds like sci-fi, but scientists hope to succeed within years