Huntsville, Alabama

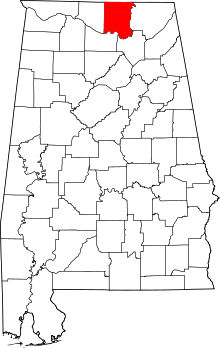

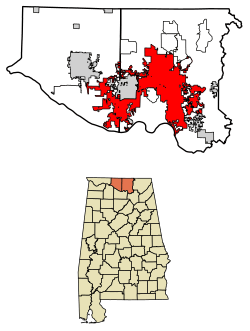

Huntsville is a city in the Appalachian region of northern Alabama.[10] It is the county seat of Madison County[11] but extends west into neighboring Limestone County[12] and south into Morgan County.[13]

Huntsville, Alabama | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Huntsville | |

Clockwise from top: Skyline from Big Spring Park, Madison County Courthouse, Shelby Center at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, view from Monte Sano Mountain, First National Bank building, U.S. Space and Rocket Center | |

| Nickname(s): "Rocket City" | |

| Motto(s): "Star of Alabama" | |

Location of Huntsville in Limestone County and Madison County, Alabama. | |

Huntsville, Alabama Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°43′48″N 86°35′6″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Counties | Madison, Limestone, Morgan[1] |

| Established (Twickenham) | December 23, 1809[2] |

| Incorporated (town) | December 9, 1811[3][4] |

| Incorporated (city) | February 24, 1860[5] |

| Founded by | LeRoy Pope |

| Named for | John Hunt |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Tommy Battle (R) |

| • Council | Huntsville City Council |

| Area | |

| • City | 218.90 sq mi (566.95 km2) |

| • Land | 217.53 sq mi (563.39 km2) |

| • Water | 1.38 sq mi (3.56 km2) |

| Elevation | 600 ft (183 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 180,105 |

| • Estimate (2019)[8] | 200,574 |

| • Rank | US: 114th AL: 2nd[9] |

| • Density | 922.07/sq mi (356.01/km2) |

| • Urban | 286,692 (US: 132nd) |

| • Metro | 462,693 (US: 117th) |

| Demonym(s) | Huntsvillian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 35649, 35749, 35748, 35754, 35756, 35757, 35671, 35741, 35762, 35763, 35773, 35801–35816, 35824, 35893-35899 |

| Area codes | 256, 938 |

| FIPS code | 01-37000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0151827 |

| Interstates | |

| U.S. Routes | |

| Website | HuntsvilleAL.gov |

It was founded in 1805 and became an incorporated town in 1811. The city grew across nearby hills north of the Tennessee River, adding textile mills, then munitions factories, NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and the United States Army Aviation and Missile Command nearby at the Redstone Arsenal. The National Trust for Historic Preservation named Huntsville to its "America's Dozen Distinctive Destinations for 2010" list.[14]

The city's population was 180,105 in 2010, making it Alabama's fourth-largest city.[7][15] Huntsville is the largest city in the five-county Huntsville-Decatur-Albertville, AL Combined Statistical Area.[16] The Huntsville metropolitan area's population was 417,593 in 2010,[17] making it the second most populous metropolitan area in the state.[18] The Huntsville metro's population reached 462,693 by 2018.[19]

History

First settlers

The first settlers of the area were Muscogee-speaking people.[20] The Chickasaw traditionally claim to have settled around 1300 after coming east across the Mississippi. A combination of factors, including disease, land disputes between the Choctaw and Cherokee, and pressures from the United States government had largely depopulated the area by the time Revolutionary War veteran John Hunt settled in the land around the Big Spring in 1805. The 1805 Treaty with the Chickasaws and the Cherokee Treaty of Washington of 1806 ceded native claims to the United States government. The area was subsequently purchased by LeRoy Pope, who named the area Twickenham after the home village of his distant kinsman Alexander Pope.[21]

Twickenham was carefully planned, with streets laid out on the northeast to southwest direction based on the flow of Big Spring. However, due to anti-British sentiment during this period, the name was changed to "Huntsville" to honor John Hunt, who had been forced to move to other land south of the new city.[22]

Both John Hunt and LeRoy Pope were Freemasons and charter members of Helion Lodge #1, the oldest Lodge in Alabama.[23]

Incorporation

In 1811, Huntsville became the first incorporated town in Alabama. However, the recognized "founding" year of the city is 1805, the year of John Hunt's arrival. The city celebrated its sesquicentennial in 1955[24] and its bicentennial in 2005.[25]

David Wade arrived in Huntsville in 1817. He built the David Wade House on the north side of what is now Bob Wade Lane (Robert B. Wade was David's grandson) just east of Mt. Lebanon Road. It had six rough Doric columns on the portico.

During the Great Depression, the Wade House was measured as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) to be included in the government's Archive and was photographed by Frances Benjamin Johnston for the project. This project put architects, draftsmen, and photographers to work to create an inventory of documentation and photographs of significant properties across the country. The house had already been abandoned for years and was considerably deteriorated. It was torn down in 1952. Today only the antebellum smokehouse, an imposing structure itself, survives at the property.[26]

Emerging industries

Huntsville's quick growth was from wealth generated by the cotton and railroad industries. Many wealthy planters moved into the area from Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas. In 1819, Huntsville hosted a constitutional convention in Walker Allen's large cabinetmaking shop. The 44 delegates meeting there wrote a constitution for the new state of Alabama. In accordance with the new state constitution, Huntsville became Alabama's first capital when the state was admitted to the Union. This was a temporary designation for one legislative session only. The capital was moved to more central cities; to Cahawba, then to Tuscaloosa, and finally to Montgomery.[27]

In 1855, the Memphis and Charleston Railroad was constructed through Huntsville, becoming the first railway to link the Atlantic seacoast with the lower Mississippi River.[28]

Civil War

Huntsville initially opposed secession from the Union in 1861, but provided many men for the Confederacy's efforts.[29] The 4th Alabama Infantry Regiment, led by Col. Egbert J. Jones of Huntsville, distinguished itself at the Battle of Manassas/Bull Run, the first major encounter of the American Civil War. The Fourth Alabama Infantry, which contained two Huntsville companies, were the first Alabama troops to fight in the war and were present when Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in April 1865. Nine generals of the war were born in or near Huntsville, split five to the Confederate and four to the Union.[30]

On the morning of April 11, 1862, Union troops led by General Ormsby M. Mitchel seized Huntsville in order to sever the Confederacy's rail communications and gain access to the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Huntsville was the control point for the Western Division of the Memphis & Charleston,[31] and by controlling this railroad the Union had struck a major blow to the Confederacy.

During the first occupation, Union officers occupied many of the larger homes in the city while the enlisted soldiers camped mainly on the outskirts. In the initial occupation, the Union troops searched for both Confederate troops hiding in the town and weapons. Since they occupied the city, treatment toward Huntsville was relatively civil. However, residents of the nearby towns did not fare as well.[32]

The Union troops were forced to retreat only a few months later, but they returned to Huntsville in the fall of 1863 and thereafter used the city as a base of operations for the war, except during the last months of 1864. While many homes and villages in the surrounding countryside were burned in retaliation for the active guerrilla warfare in the area, Huntsville itself survived because it housed Union Army troops.[32]

After the Civil War

After the Civil War, Huntsville became a center for cotton textile mills, such as Lincoln, Dallas, and Merrimack. Each mill company constructed worker housing, in communities that included schools, churches, grocery stores, theaters, and hardware stores, all within walking distance of the mill. In some of these, workers were required to buy goods at the company stores, which sometimes overcharged them. The mill owners could throw out workers from housing if they violated policies about behavior.

A dairy cow called Lily Flagg broke the world record for butter production in 1892. Her Huntsville-resident owner General Samuel H. Moore painted his house butter yellow and organized a party to celebrate, arranging for electric lights for the dance floor.[33] An area south of Huntsville was named Lily Flagg before 1906.[34][35] This area was later annexed by the city.

Great Depression 1930s

During the 1930s, industry declined in Huntsville due to the Great Depression. Huntsville became known as the Watercress Capital of the World[36] because of its abundant harvest in the area. Madison County led Alabama in cotton production during this time.[36]

World War II

By 1940, Huntsville was still relatively small, with a population of about 13,000 inhabitants. This quickly changed in early 1941 when the U.S. Army selected 35,000 acres (140 km2) of land adjoining the southwest area of the city for building three chemical munitions facilities: the Huntsville Arsenal, the Redstone Ordnance Plant (soon redesignated Redstone Arsenal), and the Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot. These operated throughout World War II, with combined personnel approaching 20,000. Resources in the area were strained as new workers flocked to the area, and the construction of housing could not keep up.[37]

Missile development

At the end of the war in 1945, the munitions facilities were no longer needed. They were combined with the designation Redstone Arsenal (RSA), and a considerable political and business effort was made in attempts to attract new tenants. One significant start involved manufacturing the Keller automobile, but this closed after 18 vehicles were built. With the encouragement of US Senator John Sparkman, the U.S. Army Air Force considered this for a major testing facility, but then selected another site. Redstone Arsenal was prepared for disposal, but Sparkman used his considerable Southern Democratic influence (the Solid South controlled numerous powerful chairmanships of congressional committees) to persuade the Army to choose it as a site for rocket and missile development.[38]

In 1950, about 1,000 personnel were transferred from Fort Bliss, Texas, to Redstone Arsenal to form the Ordnance Guided Missile Center (OGMC). Central to this was a group of about 200 German scientists and engineers, led by Wernher von Braun; they had been brought to America by Colonel Holger Toftoy under Operation Paperclip following World War II. Assigned to the center at Huntsville, they settled and reared families in this area.[39]

As the Korean War started, the OGMC was given the mission to develop what eventually became the Redstone Rocket. This rocket set the stage for the United States' space program, as well as major Army missile programs, to be centered in Huntsville. Toftoy, then a brigadier general, commanded OGMC and the overall Redstone Arsenal. In early 1956, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) under Major General John Medaris was formed.[38]

Early American space flight

The city is nicknamed "The Rocket City" for its close association with U.S. space missions.[40] On January 31, 1958, ABMA placed America's first satellite, Explorer 1, into orbit using a Jupiter-C launch vehicle, a descendant of the Redstone. This brought national attention to Redstone Arsenal and Huntsville, with widespread recognition of this being a major center for high technology.

On July 1, 1960, 4,670 civilian employees, associated buildings and equipment, and 1,840 acres (7.4 km2) of land, transferred from ABMA to form NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). Wernher von Braun was MSFC's initial director. On September 8, President Dwight D. Eisenhower formally dedicated the MSFC.[41]

During the 1960s, the major mission of MSFC was in developing the Saturn boosters used by NASA in the Apollo Lunar Landing Program. For this, MSFC greatly increased its employees, and many new companies joined the Huntsville industrial community. The Cummings Research Park was developed just north of Redstone Arsenal to partially accommodate this industrial growth, and has now became the second-largest research park of this type in America.

Huntsville's economy was nearly crippled and growth almost came to a standstill in the 1970s following the closure of the Apollo program. However, the emergence of the Space Shuttle, the International Space Station, and a wide variety of advanced research in space sciences led to a resurgence in NASA-related activities that has continued into the 21st century. In addition, new Army organizations have emerged at Redstone Arsenal, particularly in the ever-expanding field of missile defense.[42]

Now in the 2000s, Huntsville has the second-largest technology and research park in the nation,[43] and ranks among the top 25 most educated cities in the nation.[44][45][46] It is considered in the top of the nation's high-tech hotspots,[47][48] and one of the best Southern cities for defense jobs.[49] It is the number one United States location for engineers most satisfied with the recognition they receive,[50] with high average salary and low median gross rent.[51]

Biotechnology

More than 25 biotechnology firms have developed in Huntsville due to the Huntsville Biotech Initiative.[52] The HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology is the centerpiece of the 150-acre Cummings Research Park Biotech Campus, part of the 4,000-acre Cummings Research Park, which is second only to North Carolina's Research Triangle Park in land area. The non-profit HudsonAlpha Institute[53] has contributed genomics and genetics work to the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE). For-profit business ventures within the Biotech Campus[54] focus on subjects such as infectious disease diagnostics, immune responses to disease and cancer, protein crystallization, lab-on-a-chip technologies, and improved agricultural technologies. The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) created a doctoral program in biotechnology to help develop scientists to support HudsonAlpha in addition to the emerging biotechnology economy in Huntsville. The university's strategic plan has biotechnology as one of its emerging fields for future education and research.[55]

Geography

Huntsville is located at 34°42′N 86°35′W (34.7, -86.6).[56] The city has a total area of 210.0 square miles (543.9 km2).[57] Huntsville has grown through recent annexations west into Limestone County, a total of 21.5 square miles (56 km2), or 13,885 acres (5,619 ha).[58]

Situated in the Tennessee River valley, Huntsville is partially surrounded by several plateaus and large hills. These plateaus are associated with the Cumberland Plateau, and are locally called "mountains". Monte Sano Mountain (Spanish for "Mountain of Health") is the most notable, and is east of the city along with Round Top (Burritt), Chapman, Huntsville, and Green mountains.[59] Others are Wade Mountain to the north, Rainbow Mountain to the west, and Weeden and Madkin mountains on the Redstone Arsenal property in the south. Brindley Mountain is visible in the south across the Tennessee River.

As with other areas along the Cumberland Plateau, the land around Huntsville is karst in nature. The city was founded around the Big Spring, which is a typical karst spring. Many caves perforate the limestone bedrock underneath the surface, as is common in karst areas. The National Speleological Society is headquartered in Huntsville.

Boundaries

The city is primarily surrounded by unincorporated land. The following incorporated areas border parts of the city:[60]

- Athens (far northwestern tip of Huntsville)

- Decatur (southwest)

- Owens Cross Roads (southeast)

- Triana (south)

Several unincorporated communities also border Huntsville, including:

- Harvest (northwest)

- Meridianville (north)

- Moores Mill (northeast)

- New Market, Alabama (northeast – oldest Alabama settlement)

- Redstone Arsenal (U.S. Army base) (south)

The Huntsville city limits expanded west to wrap around and in 2011 fully surrounded the neighboring city of Madison.[60]

Climate

Huntsville has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa). It experiences hot, humid summers and generally mild winters, with average high temperatures ranging from near 90 °F (32.2 °C) in the summer to 49 °F (9.4 °C) during winter.

Huntsville is near the center of a large area of the U.S. mid-South that has maximum precipitation in the winter and spring, not summer. Average yearly precipitation is more than 54 inches. On average, the wettest single month is December, but Huntsville has a prolonged wetter season from November to May, with (on average) nearly or over 5 or more inches of precipitation most of those months. On average, August to October represent slightly drier months (see climate chart, showing less than 3.8 inches of precipitation these months). Droughts can occur, primarily August through October, but usually there is enough rainfall to keep soils moist and vegetation lush. Much of Huntsville's precipitation is delivered by thunderstorms. Thunderstorms are most frequent during the spring, and the most severe storms occur during the spring and late fall. These storms can deliver large hail, damaging straight-line winds, and tornadoes. Huntsville lies in a region colloquially known as Dixie Alley, an area more prone to violent, long-track tornadoes than most other parts of the US.[62][63]

On April 27, 2011, the largest tornado outbreak on record, the 2011 Super Outbreak, affected northern Alabama. During this event, an EF5 tornado that tracked near the Browns Ferry Nuclear Power Plant destroyed many transmission towers and caused a multi-day power outage for the majority of North Alabama. That same tornado also resulted in considerable damage to the Anderson Hills subdivision and in Harvest, Alabama. In total, nine people were killed in Madison County, and many others injured.[64] Other significant tornado events include the Super Outbreak in April 1974, the November 1989 Tornado Outbreak that killed 21 and injured almost 500, and the Anderson Hills Tornado that killed one and caused extensive damage in 1995.[65][66] On January 21, 2010, Huntsville experienced a rare mid-winter tornado. It registered EF2 on the Enhanced Fujita scale and resulted in moderate damage. Because it was not rain-wrapped and was easily photographed, it received extensive media coverage.[67]

Since Huntsville is nearly 300 miles (480 km) inland, hurricanes rarely arrive with their full force; however, many weakened tropical storms cross the area after a U.S. Gulf Coast landfall. While most winters have some measurable snow, heavy snow is rare in Huntsville. However, there have been some unusually heavy snowstorms, like the New Year's Eve 1963 snowstorm, when 17 in (43 cm) fell within 24 hours. Likewise, the Blizzard of 1993 and the Groundhog Day snowstorm in February 1996 were substantial winter events for Huntsville. On Christmas Day 2010, Huntsville recorded over 4 inches (10 cm) of snow, and on January 9–10, 2011 it received 8.9 inches (23 cm) at the airport and up to 10 inches (25 cm) in the suburbs.[68]

| Climate data for Huntsville, Alabama (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1894–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

108 (42) |

111 (44) |

108 (42) |

108 (42) |

100 (38) |

88 (31) |

81 (27) |

111 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.5 (20.3) |

73.4 (23.0) |

80.7 (27.1) |

85.8 (29.9) |

89.8 (32.1) |

95.0 (35.0) |

96.9 (36.1) |

96.7 (35.9) |

93.3 (34.1) |

85.7 (29.8) |

78.4 (25.8) |

69.7 (20.9) |

99.0 (37.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 51.9 (11.1) |

55.9 (13.3) |

64.9 (18.3) |

73.6 (23.1) |

81.3 (27.4) |

88.2 (31.2) |

90.7 (32.6) |

90.9 (32.7) |

85.0 (29.4) |

74.6 (23.7) |

63.7 (17.6) |

53.5 (11.9) |

72.9 (22.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 41.5 (5.3) |

45.7 (7.6) |

53.5 (11.9) |

61.8 (16.6) |

70.3 (21.3) |

77.7 (25.4) |

80.6 (27.0) |

80.1 (26.7) |

73.7 (23.2) |

62.8 (17.1) |

52.7 (11.5) |

43.9 (6.6) |

62.1 (16.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.8 (−0.1) |

35.5 (1.9) |

42.2 (5.7) |

50.0 (10.0) |

59.3 (15.2) |

67.1 (19.5) |

70.4 (21.3) |

69.4 (20.8) |

62.5 (16.9) |

51.0 (10.6) |

41.8 (5.4) |

34.4 (1.3) |

51.4 (10.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 12.2 (−11.0) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

32.7 (0.4) |

44.9 (7.2) |

55.5 (13.1) |

62.0 (16.7) |

59.7 (15.4) |

46.3 (7.9) |

33.7 (0.9) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

16.8 (−8.4) |

8.8 (−12.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −11 (−24) |

−8 (−22) |

6 (−14) |

24 (−4) |

32 (0) |

42 (6) |

49 (9) |

50 (10) |

37 (3) |

23 (−5) |

1 (−17) |

−3 (−19) |

−11 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.89 (124) |

4.84 (123) |

5.21 (132) |

4.32 (110) |

5.11 (130) |

4.29 (109) |

4.05 (103) |

3.61 (92) |

3.72 (94) |

3.59 (91) |

4.94 (125) |

5.77 (147) |

54.34 (1,380) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.1 (2.8) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

2.4 (6.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.7 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 8.5 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 9.4 | 10.8 | 116.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 56.5 | 73.5 | 71.0 | 70.0 | 70.0 | 72.5 | 73.5 | 76.0 | 74.5 | 74.0 | 70.0 | 70.5 | 75.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA[69][70][71] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: climate-zone.com[72] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 2,496 | — | |

| 1850 | 2,863 | 14.7% | |

| 1860 | 3,634 | 26.9% | |

| 1870 | 4,907 | 35.0% | |

| 1880 | 4,977 | 1.4% | |

| 1890 | 7,995 | 60.6% | |

| 1900 | 8,068 | 0.9% | |

| 1910 | 7,611 | −5.7% | |

| 1920 | 8,018 | 5.3% | |

| 1930 | 11,554 | 44.1% | |

| 1940 | 13,050 | 12.9% | |

| 1950 | 16,437 | 26.0% | |

| 1960 | 72,365 | 340.3% | |

| 1970 | 139,282 | 92.5% | |

| 1980 | 142,513 | 2.3% | |

| 1990 | 159,789 | 12.1% | |

| 2000 | 158,216 | −1.0% | |

| 2010 | 180,105 | 13.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 200,574 | [8] | 11.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[73] 2018 Estimate[74] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 158,216 people, 66,742 households, and 41,713 families residing in the city. The population density was 909.0 people per square mile (351.0/km2). There were 73,670 housing units at an average density of 423.3 per square mile (163.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 64.47% White, 30.21% Black or African American, 0.54% Native American, 2.22% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.66% from other races, and 1.84% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.04% of the population. Non-Hispanic Whites were 58% of the population in 2010,[75] compared to 86.9% in 1970.[76]

There were 66,742 households out of which 27.6% had children living with them, 45.5% were married couples living together, 13.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.5% were non-families. 32.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.91. Same-sex couple households comprised 0.5% of all households.

2010 census

.png)

As of the census of 2010, there were 180,105 people, 77,033 households, and 45,416 families residing in the city. The population density was 857.6 people per square mile (332.7/km2). There were 84,949 housing units at an average density of 405.3 per square mile (156.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 60.3% White, 31.2% Black or African American, 0.6% Native American, 2.4% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.9% from other races, and 2.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.8% of the population.

There were 77,033 households out of which 24.9% had children living with them, 40.1% were married couples living together, 14.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.0% were non-families. 34.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.25 and the average family size was 2.91.

Demographic distribution

| Age | <18 | 18-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | 65+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion (%) | 23.1 | 10.7 | 29.3 | 23.4 | 13.4 |

Sex ratio and income distribution

| Median age | 37 |

|---|---|

| Sex ratio F:M | 100:92.8 |

| Sex ratio age 18+ F:M | 100:89.7 |

| Median income | $41,074 |

| Family Median income | $52,202 |

| Male Median income | $40,003 |

| Female Median income | $26,085 |

| Per capita Income | $24,015 |

| Percent Below poverty | 12.8 |

| Age < 18 Below poverty | 18.7 |

| Age 65+ Below poverty | 9.0 |

Politics and government

The current mayor of Huntsville is Tommy Battle, who was first elected in 2008 and then re-elected in 2012 and 2016. The City Administrator is John Hamilton, who replaced Rex Reynolds on January 1, 2014 when Reynolds retired.[77] The city has a five-member/district City Council. The current members are:[78]

- District 1 (Northwest): Devyn S. Keith, Council President

- District 2 (East): Frances Akridge

- District 3 (Southeast): Dr. Jennie Robinson

- District 4 (Southwest): Bill Kling, Jr., Third Presiding Officer

- District 5 (West): Will Culver, President Pro Tempore

Council elections are staggered, meaning that Districts 2, 3, and 4 had elections in August 2018, while Districts 1 and 5 had elections simultaneously with mayoral elections in 2020.

The city has boards and commissions which control everything from schools and planning to museums and downtown development.

In July 2007, then Senator Barack Obama held the first fundraiser in Alabama for his Presidential campaign in Huntsville. Obama ended up winning the Alabama Democratic Primary in Madison County by large margins in 2008. In the general election, John McCain carried Madison County with 57% of the vote. In the 2016 general election, Donald Trump (R) carried Madison County with 55% of the vote. With Hillary Clinton (D) receiving 38%, and Gary Johnson (I) receiving 4%. Huntsville is represented in Congress by Rep. Mo Brooks (R-5th Congressional District, AL) who won re-election in 2016 with 60% of the vote.

See also: List of mayors of Huntsville, Alabama

Public safety and health

In 2007, Mayor Loretta Spencer combined the police, fire, and animal services departments to create the Department of Public Safety.[79] The former chief of police was appointed as its director. The new department has nearly 900 employees and an annual budget of $106.5 million.[80]

Fire

The Huntsville Fire and Rescue[81] provides fire protection for the city. On a daily basis the department staffs and coordinates nineteen engine companies, five ladder trucks, four rescue trucks, along with a Special Operations Division that includes Hazardous Materials Units, Technical Rescue Units, and several specialized support units. Huntsville Fire & Rescue also has Fire Investigations, emergency response dispatch, logistics, and training divisions, all of which are diverse, innovative and efficient. Many Huntsville firefighters are members of the regional Hazardous Materials and Heavy Rescue[82] response teams. The day-to-day operations of the department are currently carried out by the department's Fire Chief.

Volunteer organizations

Huntsville has two volunteer public safety organizations in their city. The Huntsville-Madison County Rescue Squad is the county wide volunteer rescue organization with tasks ranging from vehicle extrication to water rescues. The other is the Huntsville Cave Rescue Unit which is the region's only all-volunteer cave rescue organization. It is tasked with cave, cliff and high angle rope rescues. These organizations are located in Huntsville but operate both in the city and outside with HCRU responding to many cave rescue calls coming from caves well outside the city limits.

Emergency medical services

Huntsville Emergency Medical Services, Inc. (HEMSI)[83] provides emergency medical services to Huntsville and surrounding Madison county. HEMSI operates up to 22 advanced life support crews from 12 stations with a fleet of 36 ambulances fully equipped with the latest technology. HEMSI is CAAS accredited and is an IAED accredited center of excellence.

Police

The Huntsville Police Department[84] has 3 precincts and 1 downtown HQ, 400 sworn officers, 150 civilian personnel, and patrols an area of 194.7+ square miles (this number has grown due to recent annexations).

Police Academy

The Huntsville Police Academy has been in operation since 1965.[85] In 2014, the academy had graduated 53 basic classes and 7 lateral classes.[86]

Hospitals

Economy

Huntsville's main economic influence is derived from aerospace and military technology. Redstone Arsenal, Cummings Research Park (CRP), and NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center comprise the main hubs for the area's technology-driven economy. CRP is the second largest research park in the United States and the fourth largest in the world. University of Alabama in Huntsville is a center for technology and engineering research in the area. There are commercial technology companies such as the network access company ADTRAN, computer graphics company Intergraph and designer and manufacturer of IT infrastructure Avocent. Cinram manufactures and distributes 20th Century Fox DVDs and Blu-ray Discs out of their Huntsville plant. Sanmina-SCI has a presence in the area. Fifty-seven Fortune 500 companies have operations in Huntsville.[88]

In 2005, Forbes magazine named the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area as 6th best in the nation for doing business, and number one in terms of the number of engineers per total employment. In 2006, Huntsville dropped to 14th; the prevalence of engineers was not considered in the 2006 ranking.

Retail

There are several strip malls and shopping malls throughout the city. Huntsville has one enclosed mall, Parkway Place, built in 2002 on the site of the former Parkway City Mall. A larger mall built in 1984, Madison Square Mall, was closed in 2017 and the site is to be redeveloped into a lifestyle center, now known as Mid City. There is also a lifestyle center named Bridge Street Town Centre, completed in 2007, in Cummings Research Park.

Space and defense

Huntsville remains the center for rocket-propulsion research in NASA and the Army. The Marshall Space Flight Center has been designated to develop NASA's future Space Launch System (SLS),[89] and the U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command (AMCOM) is responsible for developing a variety of rocket-based tactical weapons.

Automobiles

Toyota Motor Manufacturing Alabama, located in North Huntsville Industrial Park and separate from the under-construction Mazda Toyota Manufacturing USA facility, has 1,350 employees as of 2019. The plant has plans to expand, and to employ 1,800 individuals by 2021.[90] The plant manufactures engines for Toyota vehicles.

The planned Mazda Toyota Manufacturing USA facility plans to open by 2021 with up to 4,000 employees.[91] The new plant plans to become an assembly facility where SUV's are made for both Mazda and Toyota.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Huntsville is served by several U.S. Highways, including 72, 231, 431 and an Interstate highway spur, I-565, that links Huntsville and Decatur to I-65. Alabama Highway 53 also connects the city with I-65 in Ardmore, Tennessee. Major roadways include University Drive, Governors Drive, Airport Road, Memorial Parkway and Research Park Blvd.

Cited as "Restore Our Roads", the city of Huntsville, between 2014 and 2019, will perform about $383 million worth of road construction to improve the transportation infrastructure.[92] Some of the funds for the road work comes from an increase in sales tax,[93] while others come from various sources including the Alabama Transportation Rehabilitation and Improvement Program.[94] Major road projects include:

- Memorial Parkway overpasses at Martin Road, Lily Flagg, and Mastin Lake Road

- Widening US 72 over Chapman Mountain

- Widening US 72/University Drive from Providence Main Street to County Line Road from 4 lanes to 6 lanes

- Access and intersection improvements along Memorial Parkway

- Extending the Northern Bypass from Pulaski Pike to US-231/431

- Widening Cecil Ashburn Drive over Huntsville Mountain from 2 to 4 lanes

Additional road projects include reconstructing Holmes Avenue over Pinhook Creek, widening Zierdt, Martin and Winchester Roads, widening Old Madison Pike from Cummings Research Park to the city of Madison, relocating and widening Church Street north of Downtown, relocating Wynn Drive to allow an extension of the Calhoun Community College campus, various improvements along US 431 north of Hampton Cove, creating a new Downtown Gateway with the extension of Harvard Road from Governors Drive to Williams Avenue for a direct connection to Downtown, and extending Weatherly Road to the new Grissom High School.

Public transit

Public transit in Huntsville is run by the city's Department of Parking and Public Transit.[95] The Huntsville Shuttle runs 11 fixed routes throughout the city, mainly around downtown and major shopping areas like Memorial Parkway and University Drive and has recently expanded some of the buses to include bike racks on the front for a trial program. A trolley makes stops at tourist attractions and shopping centers. The city runs HandiRide, a demand-response transit system for the handicapped, and RideShare, a county-wide carpooling program.

Railroads

Huntsville has two active commercial rail lines. The mainline is run by Norfolk Southern, which runs from Memphis to Chattanooga, Tennessee. The original depot for this rail line, the Huntsville Depot, still exists as a railroad museum, though it no longer offers passenger service.

Another rail line, formerly part of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N), successor to the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway (NC&StL), is being operated by the Huntsville and Madison County Railroad Authority (HMCRA). The line connects to the Norfolk Southern line downtown and runs 13 miles (21 km) south, passing near Ditto Landing on the Tennessee River, and terminating at Norton Switch, near Hobbs Island. This service, in continuous operation since 1894, presently hauls freight and provides transloading facilities at its downtown depot location. Until the mid-1950s, the L&N provided freight and passenger service to Guntersville and points South. The rail cars were loaded onto barges at Hobbs Island. The barge tows were taken upstream through the Guntersville Dam & Locks and discharged at Port Guntersville. Remnants of the track supporting piers still remain in the river just upstream from Hobbs Island. The service ran twice daily. L&N abandoned the line in 1984, at which time it was acquired by the newly created HMCRA, a state agency.

A third line, the Mercury and Chase Railroad, runs 10-mile (16 km) weekend tourist rides on part of another former NC&StL and L&N line from the North Alabama Railroad Museum's Chase Depot, located in the community of Chase, Alabama. Their collection includes one of the oldest diesel locomotives in existence (1926). The rail line originally connected Huntsville to NC&StL's Nashville-to-Chattanooga mainline in Decherd, Tennessee. The depot was once the smallest union station in the United States when it served the NC&StL and Memphis and Charleston Railroad, the predecessor to the Norfolk Southern.[96]

Air service

The Huntsville International Airport is served by several regional and national carriers, including Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, Frontier Airlines, Silver Airways and American Airlines. Delivery companies have hubs in Huntsville, making flights to Europe, Asia, and Mexico.[97] The airport has the highest average fares in US as of June 2014.[98]

Ports

The inland Port of Huntsville combines the Huntsville International Airport, International Intermodal Center, and Jetplex Industrial Park for truck, train and air transport. The intermodal terminal transfers truck and train cargo to aircraft. The port has on-site U.S. Customs and USDA inspectors. The port is Foreign Trade Zone No. 83.

Bicycle routes

There are several bicycle routes in the city,[99][100][101] but access to these routes can be limited.

In 2015, Alabama and Huntsville were not considered bicycle friendly.[102] There are bike paths for exercise available.[103] Huntsville's government is working to improve bicycle network within the city limits.[104] In 2020, Huntsville released a master plan for a 70-mile bicycling and walking trail, named Singing River Trail of North Alabama to connect downtown Huntsville to the cities of Madison, Decatur, and Athens.[105]

Utilities

Electricity, water, and natural gas are all provided in Huntsville by Huntsville Utilities (HU).[106] HU purchases and resells power from the Tennessee Valley Authority. TVA has two plants that provide electricity to the Huntsville area- Browns Ferry Nuclear Power Plant in Limestone County and Guntersville Dam in Marshall County. A third, Bellefonte Nuclear Power Plant in Jackson County, was built in the 1980s but was never activated. TVA plans to eventually activate the plant.[107]

Telephone service in Huntsville is provided by AT&T, EarthLink, WOW!, and Comcast. Comcast and WOW! are the two cable providers in the Huntsville city limits. Mediacom operates in rural outlying areas. AT&T announced the start of its DSL U-verse service in the Huntsville-Decatur metro area in November 2010.[108]

Media and communications

Newspapers

The Huntsville Times has been Huntsville's only daily newspaper since 1996, when the Huntsville News closed. Before then, the News was the morning paper, and the Times was the afternoon paper until 2004. The Times has a weekday circulation of 60,000, which rises to 80,000 on Sundays. Both papers were owned by the Newhouse chain.[109]

In May 2012, Advance Publications, owner of the Times, announced that the Times would become part of a new company called the Alabama Media Group,[110] along with the other three newspapers and two websites owned by Advance. As part of the change, the newspapers moved to a three-day publication schedule, with print editions available only on Wednesday, Friday and Sunday. The Huntsville Times and its sister papers publish news and information 7 days a week on AL.com.[111]

A few alternative newspapers are available in Huntsville. The Valley Planet[112] covers arts and entertainment in the Tennessee Valley area. The Redstone Rocket[113] is a newspaper distributed throughout Redstone Arsenal's housing area covering activities on Redstone. Speakin' Out News[114] is a weekly newspaper focused on African Americans. El Reportero is a Spanish-language newspaper for North Alabama.

Magazines

Huntsville Life Magazine is a lifestyle magazine, which is published six times annually.[115]

No'Ala Huntsville is a lifestyle magazine, which is published six times annually.

Radio

Huntsville is the 106th largest radio market in the United States.[116] Station KIH20 broadcasts the National Weather Service's forecasts and warnings for the Huntsville area.

Television

The Huntsville DMA serves 15 counties in North Alabama and 6 counties in Southern Middle Tennessee.

- TV Stations

- WTZT 11.1 Cozi TV (Athens)

- WHDF 15.1 CW Network Florence

- WHNT 19.1 CBS

- 19.2 WHNT2 HD

- 19.3 Antenna TV

- WHIQ 25.1 PBS/Alabama Public Television

- 25.2 APT Kids

- 25.3 APT Create

- 25.5 APT World

- 25.5 Huntsville ETV

- WAAY 31.1 ABC

- 31.2 Ion Television

- 31.3 QVC

- W34EY-D 38 3ABN

- 38.1 3ABN

- 38.2 3ABN Proclaim

- 38.3 3ABN Dare to Dream

- 38.4 3ABN Latino

- 38.5 3ABN Radio

- 38.6 3ABN Radio Latino

- 38.7 Radio 74

- WAFF 48.1 NBC

- WZDX 54.1 FOX

- 54.2 WAMY My Network TV

- 54.3 Me-TV

- 54.4 Escape

Film

A few feature films have been shot in Huntsville, including 20 Years After[117] (2008, originally released as Like Moles, Like Rats),[118] Air Band (2005),[119] and Constellation (2005).[120] Parts of the film SpaceCamp (1986) were shot at Huntsville's U.S. Space and Rocket Center at the eponymous facility. The U.S. Space and Rocket Center stood in for NASA in the 1989 movie Beyond the Stars. Columbia Pictures filmed Ravagers (1979) in The Land Trust's Historic Three Caves Quarry, at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, and at an antebellum home next door to Lee High School. The city was also referenced in Captain Marvel.

Huntsville's legacy in the space program continues to draw film producers looking for background material for space-themed films. During the pre-production of Apollo 13 (1995), the cast and crew spent time at Space Camp and Marshall Space Flight Center preparing for their roles. Space Camp was mentioned in the film Stranger than Fiction and was featured in a 2008 episode of Penn & Teller: B.S.! on NASA.

Huntsville has seven movie theaters:[121]

- AMC Valley Bend 18

- Carmike Cinemas Valley Bend 18 + IMAX

- Carmike Huntsville 10

- Monaco Pictures 14

- Regal Hollywood Stadium 18

- Touchstar Cinemas Luxury Madison Square 12

- National Geographic Theater[122]

Education

K–12 education

Most K–12 students in Huntsville attend Huntsville City Schools.[123] In the 2007–2008 school year 22,839 students attended Huntsville City Schools, 77% of all students scored at or above state and national ACT averages, and of the 1,279 members of the graduating class, "approximately 92% of the students indicated that they planned to enter a post-secondary institution for further study, 43% obtained scholarship & monetary awards", and "received 2,988 scholarships totaling $33,619,040, had forty-one National Merit Scholars, three National Achievement Scholars, and two perfect ACT scores."[124]

Of the 53 schools in the Huntsville City Schools system in 2007–2008, there were:[124]

- 25 elementary, and

- Two K–8, which serve 10,836 students.

For grades 6–12, there are 11,696 students enrolled in the following schools:

- Eleven middle schools (grades 6–8)

- Seven high schools

- Three special centers (two Schools of Choice and one Program of Choice [1B])

- Four magnet schools (two with grades K–8 and two with grades 9–12)

The two magnet elementary schools are the Academy for Academics and Arts and the Academy for Science and Foreign Language. The three magnet middle schools are Williams Technology, The Academy for Academics and Arts, and the Academy for Science and Foreign Language, and the two magnet high schools are Lee High School and New Century Technology High School.

Approximately 21 private, parochial, and religious schools serve grades pre-K–12. The city has several accredited private Christian schools, including Saint John Paul II Catholic High School,[125] Faith Christian Academy,[126] Oakwood Adventist Academy,[127] Whitesburg Christian Academy, Grace Lutheran School, and Westminster Christian Academy. Randolph School is Huntsville's only independent, private K-12 school.[128]

In 2007, 60% of HCS teachers had at least a master's degree.[124]

Budgeting

The following was the disposition of annual funding in 2007: Instructional services – 54%, Instruction support services – 15%, Operation and maintenance – 11%, capital outlay – 8%, auxiliary services – 7%, general administrative services – 3%, and debt and other expenditures – 2%.[124]

Higher education

Huntsville's higher education institutions are:

- Alabama A&M University

- J.F. Drake State Community and Technical College

- Oakwood University

- University of Alabama in Huntsville

The University of Alabama in Huntsville is the largest university serving the greater Huntsville area, with more than 7,700 students. About half of its graduates earn a degree in engineering or science, making it one of the larger producers of engineers and physical scientists in Alabama. The Carnegie Foundation ranks the school very highly as a research institution, placing it among the top 75 public research universities in the nation. UAHuntsville is also ranked a Tier 1 national university by U.S. News & World Report.

Alabama A&M University is the oldest university in the Huntsville area, dating to 1875. With over 6,000 students,[129] it is home to the AAMU Historic District with 28 buildings and four structures listed in the United States National Register of Historic Places. Oakwood University, founded in 1896, is a Seventh-day Adventist university with over 1,800 students and a member institution of the United Negro College Fund. It is one of the nation's leading producers of black applicants to medical schools and the largest HBCU in Alabama.

Various colleges and universities have satellite locations or extensions in Huntsville:

- Athens State University[130]

- Calhoun Community College[131]

- Calhoun Community College at Cummings Research Park

- Calhoun Community College at Redstone Arsenal

- Columbia College[132]

- Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University[133]

- Faulkner University[134]

- Florida Institute of Technology[135]

- Georgia Institute of Technology

- Huntsville Regional Medical Campus of the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine[136]

- Ross Medical Education Center

- Virginia College[137]

- Huntsville Hospital and Crestwood Medical Center has an accredited school of radiologic technology[138]

Culture

Historic districts

- Twickenham Historic District was chosen as the name of the first of three of the city's historic districts. It features homes in the Federal and Greek Revival architectural styles introduced to the city by Virginia-born architect George Steele about 1818, and contains the most dense concentration of antebellum homes in Alabama. The 1819 Weeden House Museum, home of female artist and poet Howard Weeden, is open to the public, as are several others in the district.

- Old Town Historic District[139] contains a variety of styles (Federal, Greek Revival, Queen Anne, and even California cottages), with homes dating from the late 1820s through the early 1900s.

- Five Points Historic District,[140] consists predominantly of bungalows built around the beginning of the 20th century, by which time Huntsville was becoming a mill town.

- Merrimack Mill Village Historic District is a historic district developed around the Merrimack Cotton Mill in 1900. The district features homes following several basic plans: Type A, a one-story, duplex shotgun house; Type B, a rectangular duplex with double central entry doors and a shed roof porch; Type J, a two-story I-house, usually with a shed roof rear addition; Type L, a two-story, cross-gable duplex with side entrances covered by shallow-pitched gable porches; and Type M, a one-story, hipped roof duplex with a shed-roof front porch. The 96 Type L houses, most of which were constructed in the first wave of construction before 1910, represent the largest collection of the type in the South.

- Lowe Mill Village & Lincoln Mill and Mill Village Historic District were born during the textile boom of the 1890s and were recognized for their historical importance in 2011 along with Dallas Mill Village.[141]

Museums

- Alabama Constitution Village features eight reconstructed Federal style buildings, with living-museum displays downtown.[142]

- Burritt on the Mountain, located on Monte Sano Mountain, is a regional history museum and regional event venue featuring a 1950s mansion, interpretive historic park, nature trails, scenic overlooks and more.[143]

- Clay House Museum is an antebellum home built c. 1853 which showcases decorative styles up to 1950 and has an outstanding collection of Noritake porcelain.[144]

- Early Works Museum is a child friendly interactive museum in downtown Huntsville.[142]

- Harrison Brothers Hardware Store, established in 1879, is the oldest operating hardware store in Alabama. Though now owned and operated by the Historic Huntsville Foundation, it is still a working store, and part museum featuring skilled craftsmen who volunteer to run the store and answer questions.[145][146]

- The Historic Huntsville Depot, completed in 1860, is the oldest surviving railroad depot in Alabama and one of the oldest surviving depots in the United States.[147]

- Huntsville Museum of Art in Big Spring International Park offers permanent displays, traveling exhibitions, and educational programs for children and adults.[148]

- North Alabama Railroad Museum is a railroad museum with over 30 pieces of rolling stock.[149]

- US Space & Rocket Center is home to the US Space Camp and Aviation Challenge programs as well as the only Saturn V rocket designated a National Historic Landmark.

- U.S. Veterans Memorial Museum displays more than 30 historical military vehicles from World War I to the present, including the world's oldest jeep. Also on display are many artifacts, memorabilia, and small arms dating back to the Revolutionary War.[150]

Parks

There are 57 parks within the city limits of Huntsville.[151] In 2013, for the fifth time in seven years, Huntsville was named a 'Playful City USA' by KaBOOM! (non-profit organization) for their efforts to provide a variety of play opportunities for children that included after school programs and parks within walking distance of home.[152]

- Big Spring International Park is a park in downtown Huntsville centered on a natural water body (Big Spring). The park contains the Huntsville Museum of Art. Festivals are held there, such as the Panoply Arts Festival and the Big Spring Jam. There are fish in the spring's niche. There is a waterfall and a constantly lit gas torch.

- Burritt on the Mountain features an eccentric, mid-century mansion and museum, an interpretive historic park depicting rural life in the 19th century, educational programs for children and adults, accessible nature trails, panoramic views of the city below and functions as a venue for popular regional events throughout the year.[153]

- Creekwood Park is a 71 acres (29 ha) park with a full-scale children's playground and dog park that connects to the Indian Creek Greenway.[154]

- Huntsville Botanical Garden features educational programs, woodland paths, broad grassy meadows and stunning floral collections.[155]

- John Hunt Park is the city's largest park with over 400 acres (160 ha) of open space, tennis courts, soccer fields and walking trails.[156]

- Jones Farm Park is a park set in Jones Valley. The park encompasses 33 acres, and offers 2 ponds, a paved trail, and a pavilion.[157]

- Land Trust of North Alabama is a member supported, non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of the natural heritage of the area, and has preserved more than 5,500 acres (22 km2) of open space, wildflower areas, wetlands, working farms, and scenic vistas in North Alabama, including 1,107 acres (448 ha) of the Monte Sano Nature Preserve (Monte Sano Mountain), 1,471 acres (595 ha) of the Blevins Gap and Green Mountain Nature Preserves (Huntsville & Green Mountains), and 935 acres (378 ha) of the Wade Mountain Nature Preserve. Volunteers have created and maintain 62 mi (100 km) of public trails – all of which are within the Huntsville city limits.[158]

- Lydia Gold Skatepark,[159] located behind the Historic Huntsville Depot, is open to the public. In 2003, it was dedicated to the late Lydia Leigh Gold (1953–1993), an area skateboarding activist in the 1980s and the former owner of "Tattooed Lady Comics and Skateboards". Helmets are the only pad requirement. No bikes, scooters, or other wheeled vehicles are allowed – only skateboards and rollerblades are permitted.[160]

- Monte Sano State Park[161] has over 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) and features hiking and bicycling trails, rustic cabins built by the Civilian Conservation Corps, campsites, full RV hook-ups, and a recently reconstructed lodge.[162]

Festivals

- February/March: Annual Maslenitsa "Spring Festival"[163] is held in late winter (February or March) in Madison County. A goodbye to Winter and welcome to Spring, it is associated with ancient pagan traditions, the Orthodox Church, and the fifteen East-European, Baltic, Central Asian, Russian, and Southern Caucasus nations represented. This annual, family-friendly event includes a menu with crêpe-like blini as its centerpiece; the festival is also called "Pancake Week". It is brought together by a partnership between Madison County, sponsoring 501(c)(3) organizations, and Kazakh, Moldovan, Ukrainian, Russian, Georgian, and other community representatives. Traditional dance, authentic regional folk-songs and instrumentals, fashions, children's activities, and wonderful foods are part and parcel of the celebration.

- April: Panoply Arts Festival[164] is an annual arts festival that began on May 14, 1982. It is presented by The Arts Council[165] and is held on the last full weekend of each April in Big Spring International Park and the Von Braun Center. The festival includes performance stages featuring presentations, demonstrations, performances, competitions, and workshops to promote the arts. There are children's activities, a Global Village, strolling performers, and nightly fireworks displays. The Southeast Tourism Society consistently ranks the festival among their "Top Twenty Events" and Governor Bob Riley has announced it as one of Alabama's top ten tourism events.[166]

- May: Rocket City Brewfest[167] is an annual craft beer festival that began in 2009 by the local Free the Hops organization.[168] Brewfest was initially held at the historical Huntsville Depot Roundhouse,[169] then once at Campus 805[170] until it moved to the Activity Field on Redstone Arsenal for a Saturday afternoon[171] filled with craft beer, cider, and music.

- June: The annual Cigar Box Guitar Festival[172] is held the first week of June at Lowe Mill Arts and Entertainment. It is the world's longest running Cigar Box Guitar festival[173] and features live music using home made instruments in the tradition, makers from across the region, and includes workshops and demonstrations.

- September: Big Spring Jam (1993–2011) was an annual three-day music festival held on the last full weekend of September in and around Big Spring International Park in downtown Huntsville. It featured a diversity of music including rock, country, Christian, kid-friendly, and oldies.[174]

- September: The Annual International Festival of North Alabama (iFest)[175] is held each Fall on the UAHuntsville Campus. This free family event offers displays from many nations, presentations, travel/historic literature, hosts in native apparel, children's activities, and other audio-visuals emblematic of the wide diversity of participating countries. In addition, there are live performances and demos by local and touring artists, as well as international food vendors, an Open Air Market, and a colorful "Parade of Nations."

- October: Con†Stellation is an annual general-interest science fiction convention.[176] Con†Stellation (also written as Con*Stellation) has been generally held over a Friday-Sunday weekend in October each year (as of 2012).

Golf courses

- Hampton Cove[177] is one of the eleven courses making up the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail; named after Hampton Cove, it features two championship 18-hole courses and one par-three course.

- Huntsville Country Club,[178] an 18-hole course with dining and banquet facilities

- The Ledges: 18 holes, dining and banquet facilities

- The Links on Redstone Arsenal is available for Military, NASA, and others that have base access. The Links has four separate 9-hole courses, a driving range, a putting and chipping green, and even play foot golf – a soccer version of golf.[179]

- Sunset Landing Golf Club (located next to the airport)

- Valley Hill Country Club features 27 holes in South Huntsville's Jones Valley.

Libraries

The Huntsville-Madison County Public Library,[180] founded in late October 1818, is Alabama's oldest continually operating library system. It has 13 branches throughout the county including one bookmobile. The Huntsville branches are the Bailey Cove Branch Library, Bessie K. Russell Branch Library, Downtown Huntsville Library, Eleanor E. Murphy Branch Library, Oscar Mason Branch Library, and Showers Center Library. The Downtown Huntsville Library Archives contains a wealth of historical resources, including displays of photographic collections and artifacts, has Alabama's highest materials circulation rate, and features daily public programs. The library system provides free public access Internet computers and wireless Internet access in all facilities.

Arts associations

Several arts groups have passed the 50-year mark: Huntsville Community Chorus Association;[181] Huntsville Art League; Theatre Huntsville (through its parent company);[182] Broadway Theatre League;[183] Fantasy Playhouse Children's Theatre;[182] Rocket City Chorus; Huntsville Symphony Orchestra;[184] and Huntsville Photographic Society among them.

Arts Huntsville

Founded in October 1962 as a non-profit, 501(c)(3) organization, the Arts Huntsville[185] (TAC) includes over 100 local arts organizations and advocates. Arts Huntsville sponsors the arts through five core programs:

- Arts Education — including the "Meet the Artist" interactive, "distance learning" program at Educational Television[186] and ArtVentures summer arts camp;

- Member services;

- the annual Panoply Arts Festival[164]

- Concerts in the Park, a series of "summer serenades under the stars" held at Big Spring International Park in partnership with the City[187]

- Community Information Services, featuring "Boost Your Buzz", an annual publicity workshop.

Arts Huntsville promotes the visual arts with two galleries: art@TAC, using the walls near the company's Von Braun Center[188] offices and the JavaGalleria. TAC supports The Bench Project[189] and the strategic planning effort to support Huntsville-Madison County's economic development goals through expanded arts and cultural opportunities known as Create Huntsville.[190]

Performing arts

- Twickenham Fest is Alabama's Premiere Summer Chamber Music Festival. Founded in 2010, this festival brings world class musicians into Huntsville to perform chamber music repertory over a week-long. This festival is free to the public due to philanthropic support from the Huntsville community.[191]

- The Huntsville Community Chorus Association[192] (HCCA) is one of Alabama's oldest performing arts organizations, with its first performance dating to December 1946 (per its website, the Mobile Opera Guild — the state's oldest — first performed in April of that year). HCCA produces chorale concerts and musical theater productions. In addition, the company features its madrigal singers; "Glitz!" (a show choir); a chamber chorale; an annual summer melodrama/fundraiser; and three children's groups: the Huntsville Community Chorus (HCC) Children's Chorale (ages 3−5); the HCC Treble Chorale (ages 6−8); and the HCC Youth Chorale (ages 9−12).

- Broadway Theatre League[193] was founded in 1959. BTL presents a season of national touring Broadway productions each year, a family-fun show, and additional season specials. Shows are presented in the Von Braun Center's Mark C. Smith Concert Hall. Recent productions include Mamma Mia!, A Chorus Line, The Color Purple, and An Evening with Patti LuPone and Mandy Patinkin.

- The Flying Monkey Arts Center[194] is in the historic Lowe Mill under the auspices of Lowe Mill ARTS and Entertainment[195] and hosts events[196] such as the traditional Cigar Box Guitar festival, the Sex Workers' Art Show, concerts, and many presentations of the Film Co-op.[197]

- Huntsville Symphony Orchestra[198] is Alabama's oldest continuously operating professional symphony orchestra, featuring performances of classical, pops and family concerts, and music education programs in public schools.

- Fantasy Playhouse Children's Theatre,[199] Huntsville's oldest children's theater, was founded in 1960. An all-volunteer organization, Fantasy Playhouse performs for the children of north Alabama on stage and off. Fantasy Playhouse Theater Academy, the organization's dance, music, and art school, teaches children and adults each year. Fantasy Playhouse regularly produces three plays a year with an additional play, A Christmas Carol, produced early each December.

- Theatre Huntsville,[200] the result of a merger between the Twickenham Repertory Company (1979–1997) and Huntsville Little Theatre (1950–1997), is a 501(c)(3), non-profit, all-volunteer arts organization that presents six plays each season in the Von Braun Center Playhouse. It produces the annual "Shakespeare on the Mountain" in an outdoor venue, such as Burritt on the Mountain. Presentations range from The Foreigner and Noises Off to the occasional musical (Little Shop of Horrors and Nunsense). In addition, TH presents drama-related workshops (stage management, stage makeup, etc.), as announced.

- Independent Musical Productions,[201] was founded in 1993 and presents at least one annual main production such as Ragtime, Civil War, 1776, Into the Woods, RENT, and Sweeney Todd. Standard and original musicals for children as well as outreach programs complete the season.

- Plays are performed at Renaissance Theatre,[202] with two stages, the MainStage (upstairs) and the Alpha Stage (downstairs), each seating about 85. The theaters are housed in the former Commissary Building for the historic Lincoln Mill Village.[203][204] In addition to well-known and mainstream titles, Renaissance produces original, controversial, and offbeat plays. It was the site for the East Coast premiere of "The Maltese Falcon."

- Merrimack Hall Performing Arts Center[205] is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that opened in 2007, after nearly $3 million in renovations to the historic building. It was once the social center of the Merrimack Mill Village in the early 1900s. The Company Store, gymnasium, and bowling alley were all there and provided a place for socialization and recreation to all of the village's residents. Merrimack Hall now includes a 302-seat performance hall, a 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) dance studio, and rehearsal and instructional spaces for musicians. Productions and performers include Menopause The Musical, Dixie's Tupperware Party, Billy Bob Thornton and The Boxmasters, Dionne Warwick, Lisa Loeb, Claire Lynch, and the Second City Comedy Troupe.

- Ars Nova School of the Arts[206] is a conservatory for music and performing arts. Ars Nova produces musical theatre, opera, and operetta for the local stage.

- The Huntsville Youth Orchestra[207] was founded by Russell Gerhart, founding conductor of the Huntsville Symphony Orchestra, in 1961. The HYO is a non-profit corporation whose purpose is to "foster, promote, and provide the support necessary for students from North Alabama to experience musical education in an orchestral setting." The organization has six ensembles: the Huntsville Youth Symphony, Sinfonia, Philharmonia, Concert Orchestra, Intermezzo Orchestra, and Novice Strings.

- Huntsville Chamber Music Guild[208] was organized in 1952 to promote and present chamber music programs; the group seeks to present recitals in which artists are presented in works of the classical masters.

- The Huntsville Ballet Company is under the non-profit Community Ballet Association, Inc. The Huntsville Ballet Company performs ballets each year such as The Nutcracker, Romeo and Juliet, The Firebird, and Swan Lake.[209]

Visual arts

- The Huntsville Museum of Art[210] opened in 1970. It purchased the largest privately owned, permanent collection of art by American women in the U.S., featuring Anna Elizabeth Klumpke, among others.[211]

- The Huntsville Photographic Society[212] started in 1956. A non-profit organization, the HPS is dedicated to furthering the art and science of photography in North Alabama.

- The Huntsville Art League[213] started in 1957, adopting the name "The Huntsville Art League and Museum Association" (HALMA). In addition to their Visiting Artists and "Limelight Artists" series, which highlight both nonresident and member artists at the home office, HAL features its members' works at galleries located in the Jane Grote Roberts Auditorium of the Huntsville-Madison County Public Library – Main, the Heritage Club, and the halls of the Huntsville Times.

Convention center and arena

The Von Braun Center, which originally opened in 1975 as the Von Braun Civic Center, has an arena capable of seating 10,000, a 2,000-seat concert hall, a 500-seat playhouse (330 seats with proscenium staging), and 150,000 square feet (14,000 m2) of convention space. Both the arena and concert hall have undergone major renovations; as a result, they have been rechristened the Propst Arena and the Mark C. Smith Concert Hall, respectively.

Local breweries

- Olde Towne Brewing

- Straight to Ale Brewery opened in 2010 in North Huntsville, later relocated to South Huntsville,[214] and then moved to Campus 805 in West Huntsville.[215]

- Yellowhammer Brewing opened in 2010 in West Huntsville.[216] It later moved to a new facility at Campus 805 in West Huntsville.

- Below the Radar Brewpub[217] opened in 2012 just a few blocks off the square in downtown Huntsville.[218]

- Salty Nut Brewery opened in 2013 in North Huntsville[219] and moved to West Huntsville on brewery row.[220]

- Mad Malts Brewing opened in late 2013 just North of downtown Huntsville under the name 'The Brew Stooges' until Fall 2015.[221][222]

- Green Bus Brewing in downtown Huntsville opened in late 2015.[223]

- InnerSpace Brewing opened in 2018 in West Huntsville, between Salty Nut Brewery and Yellowhammer Brewing.[224]

- Fractal Brewing Project[225] opened in 2019 in South Huntsville near the Municipal Ice Complex.[226]

Comedy

Huntsville is home to a number of comedy shows, including:

- Awesome Comedy Hour at The Open Bottle

- Comedy Open Mic at Copper Top Dine N Dive

- Don't Fear the Weasel Improv at Somerville Playhouse

- Epic Comedy Hour at Flying Monkey Arts / Barking Dog Theater

- Laughs and Drafts at Yellowhammer Brewing / Lost Highway Cocktail Lounge

- Shenanigans Comedy Theatre at Somerville Playhouse

- TGIM Comedy at Maggie Meyers Irish Pub

- Various Comedy Shows at Stand Up Live Comedy Club[227]

- Various Comedy Shows at Von Braun Center / Fantasy Playhouse

Other

- The National Speleological Society[228] is headquartered in Huntsville on Cave Street.

- The Von Braun Astronomical Society[229] has two observatories and a planetarium on 10 acres (40,000 m²) in Monte Sano State Park.

- The Three Caves[230] is a former rock quarry located on Kennamer Dr. which now has concerts during the summer.

Sports

Current sports franchises

- Alabama A&M Bulldogs (NCAA D-I/I-AA, SWAC) athletics

- Alabama–Huntsville Chargers (University of Alabama in Huntsville) (NCAA D-II, GSC & WCHA) athletics

- Dixie Derby Girls[231] Women's Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA)

- Huntsville Adult Soccer League[232] – Adult Amateur Soccer League

- Huntsville Havoc – Southern Professional Hockey League (SPHL)

- Huntsville hosts the annual AHSAA State Soccer Championship tournament finals in mid-May at the Huntsville Soccer Complex

- Huntsville Rockets part of Gridiron Development Football League[233]

- Huntsville Rugby Club[234] – USA Rugby South Div. II[235]

- Huntsville Speedway[236] – stock car racing

- Oakwood College Ambassadors Men's College Basketball (USCAA Div. 1)

- Rocket City Titans[237] – 2010 Inaugural Semi Pro football season. Part of the Premier South Football League.[238]

- Tennessee Valley Tigers[239] – Independent Women's Football League

Past sports franchises

- Alabama Hawks (1968–69) (Continental Football League)

- Huntsville Stars (1985–2014) – Southern League (Class AA) baseball for Milwaukee Brewers, formerly affiliated with the Oakland A's

- Huntsville Lasers (1991–92) (Global Basketball Association)

- Huntsville Blast (1993–94) (East Coast Hockey League)

- Huntsville Fire (1997–98) (Eastern Indoor Soccer League)

- Huntsville Channel Cats/Huntsville Tornado (1995–2001, 2003–04) (Southern Hockey League 1995–96; Central Hockey League 1996–2001; South East Hockey League 2003–04)

- Huntsville Flight (2001–05) (NBA Development League)

- Tennessee Valley Raptors (2005) (United Indoor Football league)*

- Alabama Hammers (2010–2015) (Professional Indoor Football League)

- Rocket City United – National Premier Soccer League (NPSL)

- Hunstville Rockets (1962–67) (Continental Football League)

Stadiums

- Joe Davis Stadium

- Goldsmith-Schiffman Field

- Milton Frank Stadium

- Louis Crews Stadium

Notable people

Sister cities

Huntsville's sister cities include:

References

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- Jordan, Michelle. "City Limits: Explaining the annexation process". City of Huntsville Blog. Huntsville, Alabama. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama: Containing The Statutes and Resolutions in Force at the end of the General Assembly in January 1823. Published by Ginn & Curtis, J. & J. Harper, Printers, New-York, 1828. Title 14. Chapter I. Section 2. pp. 106–107. "An Act directing Courts to be held in the County of Madison, &c.—Passed December 23, 1809(...)Sec 2. And be it further enacted. That the town so laid out shall be known by the name Twickenham." (Internet Archive)

- A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama: Containing The Statutes and Resolutions in Force at the end of the General Assembly in January 1823. Published by Ginn & Curtis, J. & J. Harper, Printers, New-York, 1828. Title 62. Chapter V. pp. 774–775. "An Act to Incorporate the Town of Huntsville, Madison County —Passed December 9, 1811." (Internet Archive)

- "62 – Chapter V.". A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama: Containing The Statutes and Resolutions in Force at the end of the General Assembly in January, 1823. New-York: Ginn & Curtis, J. & J. Harper, Printers. 1828. pp. 774–775.

- Acklen, William, ed. (1861). The Code of Ordnances of the City of Hunstville, With the Charter, Pursuant to an Order of the Mayor and Aldermen. Huntsville, Ala.: William B. Figures, Printer. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Census: Huntsville now second largest city in Alabama". AL.com. November 7, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- "Madison County". Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Facts & Figures". Huntsvilleal.gov. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Gattis, Paul (February 8, 2018). "Huntsville set to cross Tennessee River, annex part of Morgan County". The Huntsville Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- Storey, Deborah (February 3, 2010). "Huntsville on the list of 'Distinctive Destinations' for 2010". The Huntsville Times.

- "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Alabama's 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting - 2010 Census - Newsroom - U.S. Census Bureau". US Census Bureau Public Information Office (Press release). February 24, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2010-2018". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Pierce, Phil (February 17, 2011). "Metro Huntsville population explodes in 2010 Census, making it state's second-largest metro area". Birmingham News. al.com. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- "Metro Huntsville population explodes in 2010 Census, making it state's second-largest metro area". Al.com.

- "5 Huntsville fastest growing large metro in Alabama, added 45,100 people since 2010". Al.com. March 26, 2015.

- "Photographic image : Map of Early Indian Tribes, Culture Areas, and Linguistic Stocks" (JPG). Lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- "Notes on the History of Huntsville". History.msfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- Record, James, and John McCormick; "Huntsville, Alabama: Rocket City, U.S.A.", pamphlet published in 1953 by Strode Publishers

- Toby Norris. "Helion Lodge #1, Huntsville, Alabama". Helionlodge.org. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- "Huntsville Rewound™ (AL/USA) Rocket City USA". huntsvillerewound.com. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- "Huntsville Bicentennial Blastoff – collectSPACE: Messages". collectspace.com. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- "Our Vanishing Heritage" (PDF). Huntsvillehistorycollection.org. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- "HISTORY OF THE ALABAMA STATE CAPITOL". Alabama Historical Commission. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- Harper's Encyclopædia of United States History from 458 A.D. to 1905: Based Upon the Plan of Benson John Lossing ... Harper & brothers. 1906. p. 526.

- R.T. Cole (1966). Jeffrey D. Stocker (ed.). From Huntsville to Appomattox: R. T. Coles's History of 4th Regiment, Alabama Volunteer Infantry, C.S.A., Army of Northern Virginia,. The University of Tennessee Press. p. xiv. ISBN 1572333405.

- John H. Allan, Brian Hogan, David Lady, Arley McCormick, Mike Morrow, Emil Posey, Jacquelyn Procter Reeves, and Kent Wright. North Alabama Civil War Generals. Tennessee Valley Civil War Round Table.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cline, Wayne (1997). Alabama Railroads. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. p. 4.

- Nancy Rohr, ed. (2005). Incidents of the War: The Civil War Journal of Mary Jane Chadick. SilverThreads Publishing. ISBN 0-9707368-1-9.

- Lucinda (April 17, 2010). "Huntsville Heritage Cookbook". Cookbook of the Day. Blogspot. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- United States Geological Society (1906). Bulletin – United States Geological Survey, Volume 274. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- James Record (March 18, 2009). "Early History of the Spring City Cycling Club". Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- "NASA MSFC Notes on the History of Huntsville". History.msfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- Baker, Michael; Redstone Arsenal: Yesterday and Today, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1993-758-626/80050

- Baker, Op.Cet.

- Laney, Monique. German Rocketeers in the Heart of Dixie: Making Sense of the Nazi Past during the Civil Rights Era. New Haven Yale University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-300-19803-4.

- Marcia Dunn (August 6, 2018). "Rocket City, Alabama: Space history and an eye on the future". Associated Press.

- "Notes on Formation of the Marshall Center". History.msfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- Kenneth Kesner (September 5, 2012). "'Epicenter of missile defense' growing on Redstone Arsenal". The Huntsville Times.

- Liz Wolgemuth. "10 Best Places for Tech Jobs". Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- "The 25 Most Educated Cities In America". Business Insider. September 19, 2014.

- Leada Gore (July 27, 2016). "Most educated city in Alabama is 1 of the smartest in America". Alabama Media Group.

- Richie Bernardo (July 25, 2017). "2017's Most & Least Educated Cities in America". WalletHub.

- Richard Florida (October 24, 2013). "America's Top 25 High-Tech Hotspots". CITYLAB.

- "Huntsville named hottest city for tech jobs". WAAY Heartland Media, LLC. June 14, 2017. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- Tranette Ledford (February 5, 2009). "Best Southeastern Cities for Defense Jobs". FedSmith.

- Leada Gore (May 15, 2014). "Lots of happy engineers? National survey puts Huntsville at top of the list for employee engagement". Alabama Media Group.

- Kathryn Dill (February 24, 2015). "The Top Ten Cities for Engineers". Forbes Media.

- "Mayor Tommy Battle Announces Huntsville Biotech Initiative". HuntsvilleAL.gov. September 26, 2014. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014.