Hattusa

Hattusa (also Ḫattuša or Hattusas /ˌhɑːttʊˈsɑːs/;[1] Hittite: URUḪa-at-tu-ša, Hattic: Hattush) was the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age. Its ruins lie near modern Boğazkale, Turkey, within the great loop of the Kızılırmak River (Hittite: Marashantiya; Greek: Halys).

The Lion Gate in the south-west | |

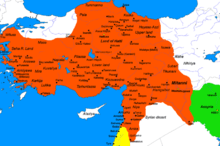

Shown within Turkey | |

| Location | Near Boğazkale, Çorum Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Anatolia |

| Coordinates | 40°01′11″N 34°36′55″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 6th millennium BC |

| Abandoned | c. 1200 BC |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Hittite |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Official name | Hattusha: the Hittite Capital |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 377 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th session) |

| Area | 268.46 ha |

Hattusa was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1986.

Surroundings

The landscape surrounding the city included rich agricultural fields and hill lands for pasture as well as woods. Smaller woods are still found outside the city, but in ancient times, they were far more widespread. This meant the inhabitants had an excellent supply of timber when building their houses and other structures. The fields provided the people with a subsistence crop of wheat, barley and lentils. Flax was also harvested, but their primary source for clothing was sheep wool. They also hunted deer in the forest, but this was probably only a luxury reserved for the nobility. Domestic animals provided meat.

There were several other settlements in the vicinity, such as the rock shrine at Yazılıkaya and the town at Alacahöyük. Since the rivers in the area are unsuitable for major ships, all transport to and from Hattusa had to go by land.

Early history

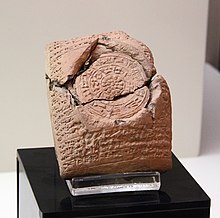

Before 2000 BC, the apparently indigenous Hattian people established a settlement on sites that had been occupied even earlier and referred to the site as Hattush. The Hattians built their initial settlement on the high ridge of Büyükkale.[2] The earliest traces of settlement on the site are from the sixth millennium BC. In the 19th and 18th centuries BC, merchants from Assur in Assyria established a trading post there, setting up in their own separate quarter of the city. The center of their trade network was located in Kanesh (Neša) (modern Kültepe). Business dealings required record-keeping: the trade network from Assur introduced writing to Hattusa, in the form of cuneiform.

A carbonized layer apparent in excavations attests to the burning and ruin of the city of Hattusa around 1700 BC. The responsible party appears to have been King Anitta from Kussara, who took credit for the act and erected an inscribed curse for good measure:

Whoever after me becomes king resettles Hattusas, let the Stormgod of the Sky strike him![3]

The Hittite imperial city

Only a generation later, a Hittite-speaking king chose the site as his residence and capital. The Hittite language had been gaining speakers at the expense of Hattic for some time. The Hattic Hattush now became the Hittite Hattusa, and the king took the name of Hattusili, the "one from Hattusa". Hattusili marked the beginning of a non-Hattic-speaking "Hittite" state and of a royal line of Hittite Great Kings, 27 of whom are now known by name.

After the Kaskians arrived to the kingdom's north, they twice attacked the city to the point where the kings had to move the royal seat to another city. Under Tudhaliya I, the Hittites moved north to Sapinuwa, returning later. Under Muwatalli II, they moved south to Tarhuntassa but assigned Hattusili III as governor over Hattusa. Mursili III returned the seat to Hattusa, where the kings remained until the end of the Hittite kingdom in the 12th century BC.

At its peak, the city covered 1.8 km² and comprised an inner and outer portion, both surrounded by a massive and still visible course of walls erected during the reign of Suppiluliuma I (circa 1344–1322 BC (short chronology)). The inner city covered an area of some 0.8 km² and was occupied by a citadel with large administrative buildings and temples. The royal residence, or acropolis, was built on a high ridge now known as Büyükkale (Great Fortress).[4]

To the south lay an outer city of about 1 km2, with elaborate gateways decorated with reliefs showing warriors, lions, and sphinxes. Four temples were located here, each set around a porticoed courtyard, together with secular buildings and residential structures. Outside the walls are cemeteries, most of which contain cremation burials. Modern estimates put the population of the city between 40,000 and 50,000 at the peak; in the early period, the inner city housed a third of that number. The dwelling houses that were built with timber and mud bricks have vanished from the site, leaving only the stone-built walls of temples and palaces.

The city was destroyed, together with the Hittite state itself, around 1200 BC, as part of the Bronze Age collapse. Excavations suggest that Hattusa was gradually abandoned over a period of several decades as the Hittite empire disintegrated.[5] The site was subsequently abandoned until 800 BC, when a modest Phrygian settlement appeared in the area.

Discovery

In 1833, the French archaeologist Charles Texier (1802–1871) was sent on an exploratory mission to Turkey, where in 1834 he discovered ruins of the ancient Hittite capital of Hattusa.[6] Ernest Chantre opened some trial trenches at the village then called Boğazköy, in 1893–94.[7] Since 1906, the German Oriental Society has been excavating at Hattusa (with breaks during the two World Wars and the Depression, 1913–31 and 1940–51). Archaeological work is still carried out by the German Archaeological Institute (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut). Hugo Winckler and Theodore Makridi Bey conducted the first excavations in 1906, 1907, and 1911–13, which were resumed in 1931 under Kurt Bittel, followed by Peter Neve (site director 1963, general director 1978–94).[8]

Cuneiform royal archives

One of the most important discoveries at the site has been the cuneiform royal archives of clay tablets, known as the Bogazköy Archive, consisting of official correspondence and contracts, as well as legal codes, procedures for cult ceremony, oracular prophecies and literature of the ancient Near East. One particularly important tablet, currently on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, details the terms of a peace settlement reached years after the Battle of Kadesh between the Hittites and the Egyptians under Ramesses II, in 1259 or 1258 BC. A copy is on display in the United Nations in New York City as an example of the earliest known international peace treaties.

Although the 30,000 or so clay tablets recovered from Hattusa form the main corpus of Hittite literature, archives have since appeared at other centers in Anatolia, such as Tabigga (Maşat Höyük) and Sapinuwa (Ortaköy). They are now divided between the archaeological museums of Ankara and Istanbul.

Sphinxes

A pair of sphinxes found at the southern gate in Hattusa were taken for restoration to Germany in 1917. The better-preserved was returned to Turkey in 1924 and placed on display in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, but the other remained in Germany where it was on display at the Pergamon Museum from 1934,[9] despite numerous requests for its return.

In 2011, threats by Turkish Ministry of Culture to impose restrictions on German archaeologists working in Turkey finally persuaded Germany to return the sphinx, and it was moved to the Boğazköy Museum outside the Hattusa ruins, along with the Istanbul sphinx[10] - reuniting the pair near their original location.

See also

- Ancient settlements in Turkey

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- Hittites

- List of megalithic sites

- Short chronology timeline

- Yazılıkaya

Notes

- "Hattusas". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- The Excavations at Hattusha: "A Brief History" Archived 2012-05-27 at Archive.today

- Hamblin, William J. Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Büyükkale

- Beckman, Gary (2007). "From Hattusa to Carchemish: The latest on Hittite history" (PDF). In Chavalas, Mark W. (ed.). Current Issues in the History of the Ancient Near East. Claremont, California: Regina Books. pp. 97–112. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- See:

- Texier, Charles (1835). "Rapport lu, le 15 mai 1835, à l'Académie royale des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres de l'Institut, sur un envoi fait par M. Texier, et contenant les dessins de bas-reliefs découverts par lui près du village de Bogaz-Keui, dans l'Asie mineure" [Report read on 15 May 1835 to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Belle-lettres of the Institute, on a dispatch made by Mr. Texier and containing drawings of bas-reliefs discovered by him near the village of Bogaz-Keui [now: Boğazkale] in Asia Minor]. Journal des Savants (in French): 368–376.

- Texier, Charles (1839). Description de l'Asie Mineure: faite par ordre du gouvernement français en 1833–1837 … [Description of Asia Minor: done by order of the French government in 1833–1837 …] (in French). vol. 1. Paris, France: Didot Frères. pp. 209ff. Available at: University of Heidelberg, Germany

- Bittel, Kurt (1983). "Quelques remarques archéologiques sur la topographie de Hattuša" [Some archaeological remarks on the topography of Hattusa]. Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 127 (3): 485–509.

- "The Excavations at Hattusha - a project of the German Institute of Archaeology": Discovery Archived 2010-04-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Jürgen Seeher, "Forty Years in the Capital of the Hittites: Peter Neve Retires from His Position as Director of the Ḫattuša-Boğazköy Excavations" The Biblical Archaeologist 58.2, "Anatolian Archaeology: A Tribute to Peter Neve" (June 1995), pp. 63-67.

- ,Article: "Germany returns Sphinx of Hattusa to Turkey" Check

|url=value (help). 2011-05-13. - Article: "Hattuşa reunites with sphinx" Check

|url=value (help). Hürriyet Daily News. 2011-11-07.

Bibliography

- Neve, Peter (1992). Hattuša-- Stadt der Götter und Tempel : neue Ausgrabungen in der Hauptstadt der Hethiter (2., erw. Aufl. ed.). Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-1478-7.

- W. Dörfler et al.: Untersuchungen zur Kulturgeschichte und Agrarökonomie im Einzugsbereich hethitischer Städte. (MDOG Berlin 132), 2000, 367-381. ISSN 0342-118X

Further reading

- Bryce, Trevor. Life and Society in the Hittite World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- --. Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East: The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age. London: Routledge, 2003.

- --. The Kingdom of the Hittites. Rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Collins, Billie Jean. The Hittites and Their World. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2007.

- Neve, Peter. “The Great Temple in Boğazköy-H ̮attuša.” In Across the Anatolian Plateau: Readings in the Archaeology of Ancient Turkey. Edited by David C. Hopkins, 77–97. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research, 2002.

- Kuhrt, Amelie. “The Hittites.” In The Ancient Near East, c. 3000–330 BC. 2 vols. By Amelie Kuhrt, 225–282. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Singer, Itamar. “A City of Many Temples: H ̮attuša, Capital of the Hittites.” In Sacred Space: Shrine, City, Land: Proceedings of the International Conference in Memory of Joshua Prawer, Held in Jerusalem, 8–13 June 1992. Edited by Benjamin Z. Kedar and R. J. Z. Werblowsky, 32–44. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

- Yazıcı, Çağlan. The Hittite Capital Hattusa, Alacahöyük and Shapinuwa: A Journey to the Hittite World In Hattusa, Alacahöyük, Shapinuwa, Eskiapar, Hüseyindede, Pazarlı and the Museums of Boğazköy, Alacahöyük and Çorum. 1st edition. Istanbul: Uranus Photography Agency and Publishing Co., 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hattusa. |

| Library resources about Hattusa |

- Excavations at Hattusha: a project of the German Institute of Archaeology

- Hittite version of the Peace treaty with Ramses II of 1283 BC

- Pictures of the old Hittite capital with links to other sites

- Hattusas

- UNESCO World Heritage page for Hattusa

- Video of lecture at Oriental Institute on Boğazköy

- A Brief History of Hattusha/Boğazköy

- Photos from Hattusa