Hisarlik, Canakkale

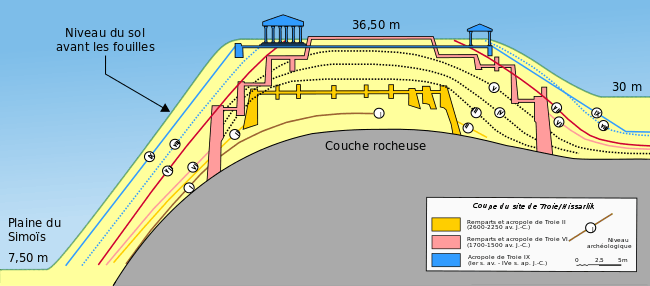

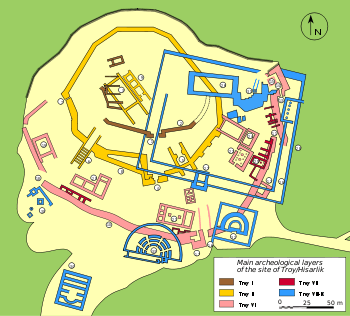

Hisarlik (Turkish: Hisarlık, "Place of Fortresses"), often spelled Hissarlik, is the Turkish name for an ancient city located in what is known historically as Anatolia, Turkish anadolu.[note 1] It is part of Çanakkale, Turkey.[1] The archaeological site lies approximately 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) from the Aegean Sea and about the same distance from the Dardanelles. The site is a partial tell, or artificial hill, elevated in layers over an original site. In this case the original site was already elevated, being the west end of a ridge projecting in an east–west direction from a mountain range.

Turkish: Hisarlık | |

Hisarlik from above | |

Shown within Marmara  Hisarlik, Canakkale (Turkey) | |

| Alternative name | Troy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39.957°N 26.239°E |

After many decades of scientific and literary study by specialists, the site is generally accepted by most as the location of ancient Troy, the city mentioned in ancient documents of many countries in several ancient languages, especially ancient Greek, where it appears as Ilion in the earliest literary work of Europe, the Iliad.[2] The site is still being excavated under the name of Troja. It also has been promoted as a major tourist attraction visited by many thousands of persons per year. A Turkish village, Tevfikiye, has been created on the east end of Troy Ridge, as it is now universally termed, to service the site and its visitors and students.

Geography

Located at the edge of a cape projecting into the Aegean between the Dardanelles and the Gulf of Edremit, which was known in antiquity as the Troad, Hisarlik was one of many successful pockets of human civilization which arose and prospered in Anatolia. Paleogeographic studies carried out around Hisarlik by John C. Kraft, head of the Geology Department of the University of Delaware and Professors Ilhan Kayan and Oğuz Erol from Ankara University indicate a favourable environment for settlement existed from around the eighth millennium BC, when receding seas left a fertile, well watered plain which over time became a shallow, but navigable estuary. Above this natural harbour, the hill was large enough to support extensive building, providing natural protection from invasion and a commanding view of the sea.

Human settlement in the region

Elsewhere in Anatolia, there is abundant archaeological evidence of a thriving neolithic culture at least as early as the seventh millennium BC. What may have been the world's first urban settlement (c. 7500 BC) has been uncovered at Çatalhüyük in the Konya Ovasi (Konya Basin). Evidence from a cave at Karain near Antalya shows human occupation in the region extending over an estimated 25,000 year period.

The inhabitants of Hisarlik lived among a number of vigorous, interactive and often warlike cultures. Apart from the mainland Greeks whence they may have sprung, the Trojans counted such neighbours as the Hittites, Phrygians and Lydians. It has been suggested that the polity at ancient Hisarlik might be one and the same with that known to the Hittites as Wilusa.[3]

The unbroken occupation of the region around Hisarlik continued with the arrival of the Romans. Finally, after several centuries of trying, the Greeks gained control of the region once ruled by the Trojans. Around 1050–800 BC, Ionian Greek refugees fled to Anatolia, to escape the Dorians. Many cities were founded along the Anatolian coast during the great period of Greek expansion after the eighth century BC. One of these, Byzantium, a distant colony established on the Bosporus by the city-state of Megara, grew to supplant Rome and ultimately proved the downfall of Troy as it dominated all maritime and overland trade for almost 22 centuries.

The region around Hisarlik is still inhabited by the descendants of the many and varied peoples who laid claim to the shores and hillsides of Anatolia. Present day Çanakkale is a thriving settlement close to the ancient site of Hisarlik. Çanakkale lies on both sides of the Dardanelles and touches both Europe (Gelibolu Peninsula) and Asia (Biga Peninsula) and just as it was in the time of Homer, maritime traffic connects both sides of the straits.

Troy

The assumed location of Troy was apparently well known in the ancient world, visited by Alexander the Great[4] and Julius Caesar.[5] In more modern times, a site associated with Ilium (and more readily identifiable as Hisarlik) was being shown to curious visitors as early as the 15th century, when Pedro Tafur was guided from the Genoese port of Fojavecchia (Phocaea):

I travelled by land for two days to that place which they say was Troy, but found no one who could give me any information concerning it, and we came to Ilium, as they call it. This place is situated on the sea opposite the harbour of Tenedos. The whole of this country is strewn with villages, and the Turks regard the ancient buildings as relics and do not destroy anything, but they build their houses adjoining. That which made me understand that this was, indeed, ancient Troy, was the sight of such great ruined buildings, and so many marbles and stones, and that shore, and the harbour of Tenedos over against it, and a great hill which seemed to have been made by the fall of some huge building.[6]

Tafur, like most early visitors, was distracted by the more prominent Hellenistic and Roman remains close to the modern shoreline.

While the archaeological record has much to say about the physical remains, it reveals little about the people who built and rebuilt the fabled city of Troy. The historical record for Troy is dominated by the epic poems of Homer and peopled with gods and heroes whose identities and histories formed part of the oral tradition of the area for centuries before the great Greek poet committed some of them to verse. Homer was not, however, overly concerned with history. Not surprisingly, the historical context for the epic Iliad and Odyssey is not as clear as one would wish. Various attempts have been made over time to identify the origins of the inhabitants of Troy.

As early as 1946, American classical art historian Rhys Carpenter argued that the Trojan War, far from being a historical event, was in fact a synthesis of many such events involving peoples whose mutual involvement stretched back centuries.[7] In the Iliad, the word most commonly used for the city of the Trojans is not "Troy" but "Ilion". Carpenter saw this as evidence of the possibility that Troy was not the name of a town at all, but rather the name of an area or district inhabited by the Trojans. The Greeks clearly had a legend about a war against the Trojans, but may have disagreed about where these people lived. At least one group of Greeks put them at a place called Teuthrania in the area known as Mysia.

Carpenter suggests that the real "Troy" is located in neither the Troad nor Aeolis but rather that the memory of a pan-Achaean expedition elsewhere was located at two different points in Asia Minor by later poetic traditions: at Ilion by the Ionic poets, because they found in this area a local folk tradition about a strong citadel sacked near the end of the Bronze Age (Hisarlik); and at Teuthrania by the Aeolic poets, to correspond with Aeolic traditions connected with their own occupation of this area.

If one is willing to accept Carpenter's line of argument this far, one can place "Troy" virtually anywhere in the eastern Mediterranean where bands of Mycenaean Greeks may have undertaken joint piratic raids. Carpenter goes so far as to place "Troy" in Egypt and to connect the story of the Trojan War with the raids of the Sea Peoples mentioned in Egyptian sources at the end of the 13th and beginning of the 12th centuries BC.

The tangled and fragile skein of inference in the historical record gives no certainty as to the origin of the inhabitants but the fact remains that for over two millennia a thriving civilisation existed at Hisarlik.

Homer's interest in Troy ends with the fall of the city. Glimpses are recorded of the fallen city, walls burning, looting and destruction and a fleeing populace including Aeneas, carrying his father Anchises away from the scene of devastation and unknowingly into a new and glorious future on alien shores. Troy's history does not end with the fall of Priam's city. The history of Troy is inextricably linked with the Bronze Age and later cultures of Anatolia, the name of which is from the Greek word for sunrise, anatole

Archaeological excavation

An alternative site, Hisarlik tell, a thirty-meter-high mound, was identified as a possible site of ancient Troy by a number of amateur archaeologists in the early to mid 19th century. The most dedicated of these was Frank Calvert, whose early work was overshadowed by the German amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in the 1870s.[8]

The site of Hisarlik has been under near-constant archaeological excavation ever since Schliemann began in 1873.[9] While much has been discovered about the structural layout of the many layers of occupation, there has been a paucity of writing found from before the classical era. In fact, the only written document heretofore discovered is a small cylinder seal with an inscription in Luwian.[9]

Troy VII is an archaeological layer of Hisarlik that chronologically spans from c. 1300 to c. 950 BC. It coincides with the collapse of the Bronze Age and is thought to be the Troy mentioned in Ancient Greece and the site of the Trojan War.[10]

Notes

- A compound of the noun, hisar, "fortification," and the suffix -lik.

Look up hisar in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

. The suffix does not create a plural, which would be hisarler, but an abstract, "fortification-place," where "fortification" is of indefinite number; i.e., one or many. The current translation appears in Cline 2013, p. 1.

Look up -lik in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

References

- Shaheen, Kareem (20 September 2017). "Archaeologists home in on Homeric clues as Turkey declares year of Troy". The Guardian.

- The story of the discovery and identification is told in Wood 1993, Ch. 1-2

- http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsMiddEast/AnatoliaTroy.htm

- https://www.livius.org/aj-al/alexander/alexander_t03.html

- Deuel, Leo (1977). Memoirs of Heinrich Schliemann. New York: Harper & Row. p. 131. ISBN 9780060111069.

- Pedro Tafur, Andanças e viajes,ch. XIII; the text written in 1453/54 recounts a voyage of the 1430s.

- Rhys Carpenter (1946). Folk Tale, Fiction and Saga in the Homeric Epics. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02808-1.

- Susan Heuck Allen (1999). Finding the Walls of Troy: Frank Calvert and Heinrich Schliemann at Hisarlík. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20868-1.

- http://www.livescience.com/38191-ancient-troy.html

- I.E.S. Edwards; C.J. Gadd; N.G.L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (18 September 1975). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-0-521-08691-2.

Reference bibliography

- Cline, Eric H. The Trojan War: A Very Short Introduction. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wood, Michael (1998). In Search of the Trojan War. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21599-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). Copyrighted in 1985, this book was published in a number of paperback and hardcover formats in the later 20th century, all of which, however, kept the same pagination. The year and the publisher varied. This citation is only an example. In the references, "Wood, 1993" can refer to any of them.