Phellus

Phellus (Lycian: Wehnti; Ancient Greek: Φέλλος, Turkish: Phellos) is an town of ancient Lycia, now situated on the mountainous outskirts of the small town of Kaş in the Antalya Province of Turkey. The city was first referenced as early as 7 BC by Greek geographer and philosopher Strabo in Book XII of his Geographica (which detailed settlements in the Anatolia region), alongside the port town of Antiphellus; which served as the settlement's main trade front.

Φέλλος Phellos | |

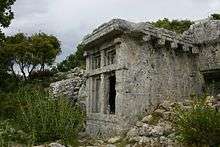

One of the many ruined tombs at Phellus, situated in the Western Taurus Mountains. | |

Shown within Turkey | |

| Location | Kaş, Antalya Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Lycia |

| Coordinates | 36°24′17″N 29°48′28″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1840 |

| Archaeologists | Sir Charles Fellows |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Public access | Yes |

Its exact location, particularly in regard to Antiphellus, was misinterpreted for many years. Strabo incorrectly designates both settlements as inland towns, closer to each other than is actually evident today. Additionally, upon its rediscovery in 1840 by Sir Charles Fellows, the settlement was located near the village of Saaret, west-northwest of Antiphellus. Verifying research into its location in ancient text proved difficult for Fellows, with illegible Greek inscriptions providing the sole written source at the site. However, Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt details in his 1847 work Travels in Lycia that validation is provided in the words of Pliny the Elder, who places Phellus north of Habessus (Antiphellus' pre-Hellenic name).

Expeditions

Fellows Expedition

Sir Charles Fellows participated in two largely successful expeditions to Lycia, in 1838 and 1840 respectively.[1] During which, he discovered large settlements such as Xanthos, Tlos, Pinara and Cadyanda in order to map their locations and bring back artifacts for public display in the United Kingdom (specifically The British Museum).[1][2] In the process, he also came to discover six other, smaller locations, one of which being the site of what is now known as Phellus.[1] Fellows had named all six settlements himself, without regard to thorough classical research; which inevitably altered the original names given at the time of occupation. For instance, Fellows' 'Gagae' was actually Corydala, and Phellus is initially referenced as 'Pyrrha' by the Roman Empire (in honour of the Greek myth that was detailed in Ovid's Metamorphoses)[3] according to the works of Pliny the Elder.[4][5]

Spratt Expedition

In 1841 the crew of HMS Beacon, headed by shipmaster Richard Hoskyn, located and traveled to several Lycian archaeological sites under the request of Thomas Graves.[1] Many of the settlements in question had already been discovered by Charles Fellows in the previous year, including the valley of Xanthos, despite the crew being unaware of this fact at the time.[1] The expedition was short in duration, and only accomplished basic surveillance of archaeological sites for the most part.[4] However, the group had initiated the restoration of Cybriatic settlements, including that of Balbura, Podalia, Massicytus and Oenoanda, all of which had been discovered and named by the expedition after journeying into the mainland of the Antalya Province (although Araxa is the more consensually approved name for Massicytus).[4][6] Hoskyn's findings and experiences were later documented in the journal for the Royal Geographical Society in 1843.[4]

An expedition to the Lycian region under the guidance of Vice-Admiral Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt was to follow. The group set about continuing the work of Hoskyn and his assistant, W.S. Harvey in the restoration of the archaeological sites discovered by Sir Charles Fellows, with work commencing on recently rediscovered settlements such as Rhodiapolis, Candyba, and indeed, Phellus (among other locations).[4] Though Phellus had already been uncovered by Fellows, Spratt also wanted to charter and survey the site, consulting the works of Roman scholars Livy and Pliny the Elder in order to verify the location of the ruins; citing Livy's claim of a town near Phoenicus that acted as "the port of Phellus",[7] and Pliny the Elder's writings, which suggest that Phellus is directly north of Habessus, a pre-Hellenic name for the settlement's trading port, Antiphellus.[5] Using these clues, Spratt journeyed to the small farming village of Saaret, which is North north-west of Antiphellus in order to locate the ruins of Phellus.[8] He was accompanied by the same guide Charles Fellows had used to document the settlement for reliability purposes, who was named Pagniotti.[9] If his cartography had been correct, Spratt could verify Phellus' location through a correlation of the ancient texts and the site notes taken by Fellows; especially toward remarks of its close proximity and adjacency to the Island of Megiste.[9]

Legacy

Phellus remains a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church.[10]

References

- Spratt (1847), p. 13

- Auerbach, Hoffenberg (2013), p. 185

- Ovid (1997), p. 118

- Spratt (1847), p. 14

- Pliny the Elder (1848), p. 93

- Spratt (1847), p. 267

- Livy (1836), p. 296

- Spratt (1847), p. 59

- Spratt (1847), p. 58

- Catholic Hierarchy

Bibliography

- Auerbach, Jeffrey; Hoffenberg, Peter (2013). Britain, the Empire, and the World at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1409480082.

- Livius Patavinus, Titus (1836). Livy: Book XXXI-XXXVIII. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 613192896.

- Ovidius Naso, Publius (1997). Ovid's Metamorphoses, Books 1-5. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806128948.

- Plinius Secundus, Gaius (1848). Pliny's Natural History. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 578716495.

- Spratt, Thomas (1847). Travels in Lycia, Milyas, and the Cibyratis. London: J. Van Voorst. OCLC 582161294.