Khoisan languages

The Khoisan /ˈkɔɪsɑːn/ languages (also Khoesan or Khoesaan) are a group of African languages originally classified together by Joseph Greenberg.[1][2] Khoisan languages share click consonants and do not belong to other African language families. For much of the 20th century, they were thought to be genealogically related to each other, but this is no longer accepted. They are now held to comprise three distinct language families and two language isolates.

| Khoisan | |

|---|---|

| Khoesaan | |

| (obsolete) | |

| Geographic distribution | Kalahari Desert, central Tanzania |

| Linguistic classification | (term of convenience) |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | khi |

| Glottolog | None |

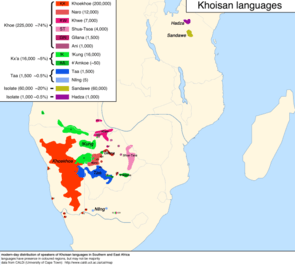

Map showing the distribution of the Khoisan languages (yellow) | |

All Khoisan languages but two are indigenous to southern Africa and belong to three language families. The Khoe family appears to have migrated to southern Africa not long before the Bantu expansion.[3] Ethnically, their speakers are the Khoikhoi and the San (Bushmen). Two languages of east Africa, those of the Sandawe and Hadza, originally were also classified as Khoisan, although their speakers are ethnically neither Khoikhoi nor San.

Before the Bantu expansion, Khoisan languages, or languages like them, were likely spread throughout southern and eastern Africa. They are currently restricted to the Kalahari Desert, primarily in Namibia and Botswana, and to the Rift Valley in central Tanzania.[2]

Most of the languages are endangered, and several are moribund or extinct. Most have no written record. The only widespread Khoisan language is Khoekhoe (or Nàmá) of Namibia, with a quarter of a million speakers; Sandawe in Tanzania is second in number with some 40–80,000, some monolingual; and the ǃKung language of the northern Kalahari spoken by some 16,000 or so people. Language use is quite strong among the 20,000 speakers of Naro, half of whom speak it as a second language.

Khoisan languages are best known for their use of click consonants as phonemes. These are typically written with characters such as ǃ and ǂ. Clicks are quite versatile as consonants, as they involve two articulations of the tongue which can operate partially independently. Consequently, the languages with the greatest numbers of consonants in the world are Khoisan. The Juǀʼhoan language has 48 click consonants among nearly as many non-click consonants, strident and pharyngealized vowels, and four tones. The ǃXóõ and ǂHõã languages are even more complex.

Grammatically, the southern Khoisan languages are generally analytic, having several inflectional morphemes, but not as many as the click languages of Tanzania.

Validity

Khoisan was proposed as one of the four families of African languages in Joseph Greenberg's classification (1949–1954, revised in 1963). However, linguists who study Khoisan languages reject their unity, and the name "Khoisan" is used by them as a term of convenience without any implication of linguistic validity, much as "Papuan" and "Australian" are.[4][5] It has been suggested that the similarities of the Tuu and Kxʼa families are due to a southern African Sprachbund rather than a genealogical relationship, whereas the Khoe (or perhaps Kwadi–Khoe) family is a more recent migrant to the area, and may be related to Sandawe in East Africa.[3]

Ernst Oswald Johannes Westphal is known for his early rejection of the Khoisan language family (Starostin 2003). Bonny Sands (1998) concluded that the family is not demonstrable with current evidence. Anthony Traill at first accepted Khoisan (Traill 1986), but by 1998 concluded that it could not be demonstrated with current data and methods, rejecting it as based on a single typological criterion: the presence of clicks.[6] Dimmendaal (2008) summarized the general view with, "it has to be concluded that Greenberg's intuitions on the genetic unity of Khoisan could not be confirmed by subsequent research. Today, the few scholars working on these languages treat the three [southern groups] as independent language families that cannot or can no longer be shown to be genetically related" (p. 841). Starostin (2013) accepts a relationship between Sandawe and Khoi is plausible, as is one between Tuu and Kxʼa, but sees no indication of a relationship between Sandawe and Khoi on the one hand and Tuu and Kxʼa on the other, or between any of them and Hadza.

Janina Brutt-Griffler claims, "given that such colonial borders were generally arbitrarily drawn, they grouped large numbers of ethnic groups that spoke many languages." She hypothesizes that this took place within efforts to prevent the spread of English during European colonization and prevent the entrance of the majority into the middle class.[7]

Khoisan language variation

Anthony Traill noted the Khoisan languages' extreme variation.[8] Despite their shared clicks, the Khoisan languages diverge significantly from each other. Traill demonstrated this linguistic diversity in the data presented in the below table. The first two columns include words from the two Khoisan language isolates, Sandawe and Hadza. The following three are languages from the Khoe family, the Kxʼa family, and the Tuu family, respectively.

| Sandawe | Hadza | Khoe | Ju | ǃXóõ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'person' | ǀnomese | ʼúnù | khoe | ʒú | tâa |

| 'man' | ǀnomese | ɬeme | kʼákhoe | ǃhõá | tâa á̰a |

| 'child' | ǁnoό | waʼa | ǀūá | dama | ʘàa |

| 'ear' | kéké | ɦatʃʼapitʃʼi | ǂée | ǀhúí | ǂnùhã |

| 'eye' | ǀgweé | ʼákhwa | ǂxái | ǀgàʼá | ǃʼûĩ |

| 'ostrich' | saʼútà | kénàngu | ǀgáro | dsùú | qûje |

| 'giraffe' | tsʼámasu | tsʼókwàna | ǃnábe | ǂoah | ǁqhūũ |

| 'buffalo' | ǀeu | nákʼóma | ǀâo | ǀàò | ǀqhái |

| 'to hear' | khéʼé | ǁnáʼe | kúm | tsʼàʼá | tá̰a |

| 'to drink' | tsʼee | fá | kxʼâa | tʃìi | kxʼāhã |

Families

The branches that were once considered part of so-called Khoisan are now considered independent families, since it has not been demonstrated that they are related according to the standard comparative method.

See Khoe languages for speculations on the linguistic history of the region.

Hadza

With about 800 speakers in Tanzania, Hadza is no longer seen as a Khoisan language and appears to be unrelated to any other language. Genetically, the Hadza people are unrelated to the Khoisan peoples of Southern Africa, and their closest relatives may be among the Pygmies of Central Africa.

Sandawe

There is some indication that Sandawe (about 40,000 speakers in Tanzania) may be related to the Khoe family, such as a congruent pronominal system and some good Swadesh-list matches, but not enough to establish regular sound correspondences. Sandawe is not related to Hadza, despite their proximity.

Khoe

The Khoe family is both the most numerous and diverse family of Khoisan languages, with seven living languages and over a quarter million speakers. Although little Kwadi data is available, proto-Khoe–Kwadi reconstructions have been made for pronouns and some basic vocabulary.

- ?Khoe–Kwadi

- Kwadi (extinct)

- Khoe

- Khoekhoe This branch appears to have been affected by the Kxʼa–Tuu sprachbund.

- Nama (ethnonyms Khoekhoen, Nama, Damara) (a dialect cluster including ǂAakhoe and Haiǁom)

- Eini (extinct)

- South Khoekhoe

- Korana (moribund)

- Xiri (moribund; a dialect cluster)

- Tshu–Khwe (or Kalahari) Many of these languages have undergone partial click loss.

- East Tshu–Khwe (East Kalahari)

- Shua (a dialect cluster including Deti, Tsʼixa, ǀXaise, and Ganádi)

- Tsoa (a dialect cluster including Cire Cire and Kua)

- West Tshu–Khwe (West Kalahari)

- East Tshu–Khwe (East Kalahari)

- Khoekhoe This branch appears to have been affected by the Kxʼa–Tuu sprachbund.

A Haiǁom language is listed in most Khoisan references. A century ago the Haiǁom people spoke a Ju dialect, probably close to ǃKung, but they now speak a divergent dialect of Nama. Thus their language is variously said to be extinct or to have 18,000 speakers, to be Ju or to be Khoe. (Their numbers have been included under Nama above.) They are known as the Saa by the Nama, and this is the source of the word San.

Tuu

The Tuu family consists of two language clusters, which are related to each other at about the distance of Khoekhoe and Tshukhwe within Khoe. They are typologically very similar to the Kxʼa languages (below), but have not been demonstrated to be related to them genealogically (the similarities may be an areal feature).

- Tuu

- Taa

- ǃXoon (4200 speakers. A dialect cluster.)

- Lower Nossob (Two dialects, ǀʼAuni and ǀHaasi. Extinct.)

- ǃKwi

- Taa

Kxʼa

The Kxʼa family is a relatively distant relationship formally demonstrated in 2010.[11]

Other "click languages"

Not all languages using clicks as phonemes are considered Khoisan. Most others are neighboring Bantu languages in southern Africa: the Nguni languages (Xhosa, Zulu, Swazi, Phuthi, and Northern Ndebele); Sotho; Yeyi in Botswana; and Mbukushu, Kwangali, and Gciriku in the Caprivi Strip. Clicks are spreading to a few additional neighboring languages. Of these languages, Xhosa, Zulu, Ndebele and Yeyi have intricate systems of click consonants; the others, despite the click in the name Gciriku, more rudimentary ones. There is also the South Cushitic language Dahalo in Kenya, which has dental clicks in a few score words, and an extinct and presumably artificial Australian ritual language called Damin, which had only nasal clicks.

The Bantu languages adopted the use of clicks from neighboring, displaced, or absorbed Khoisan populations (or from other Bantu languages), often through intermarriage, while the Dahalo are thought to have retained clicks from an earlier language when they shifted to speaking a Cushitic language; if so, the pre-Dahalo language may have been something like Hadza or Sandawe. Damin is an invented ritual language, and has nothing to do with Khoisan.

These are the only languages known to have clicks in normal vocabulary. Occasionally other languages are said by laypeople to have "click" sounds. This is usually a misnomer for ejective consonants, which are found across much of the world, or is a reference to paralinguistic use of clicks such as English tsk! tsk!

Notes

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1955. ''Studies in African Linguistic Classification.'' New Haven: Compass Publishing Company. (Reprints, with minor corrections, a series of eight articles published in the ''Southwestern Journal of Anthropology'' from 1949 to 1954.)

- Barnard, A (1988). "Kinship, language and production: a conjectural history of Khoisan social structure". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 58 (1): 29–50. doi:10.2307/1159869.

- Güldemann, Tom and Edward D. Elderkin (forthcoming) 'On external genealogical relationships of the Khoe family. Archived 2009-03-25 at the Wayback Machine' In Brenzinger, Matthias and Christa König (eds.), Khoisan Languages and Linguistics: the Riezlern Symposium 2003. Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 17. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

- Bonny Sands (1998) Eastern and Southern African Khoisan: Evaluating Claims of Distant Linguistic Relationships. Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, Cologne

- Dimmendaal, Gerrit (2008). "Language Ecology and Linguistic Diversity on the African Continent". Language and Linguistics Compass. 2 (5).

- Linguistics 112 lecture, Department of Linguistics, University of the Witwatersrand, March 1998

- Brutt-Griffler, Janina (2006). "Language endangerment, the construction of indigenous languages and world English". In Fishman, Joshua A. (ed.). 'Along the Routes to Power' Explorations of Empowerment through Language. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Traill, Anthony. "Khoisan languages". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- Güldemann, Tom; Vossen, Rainer (2000). "Khoisan". In Heine, Bernd; Nurse, Derek (eds.). African Languages: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–122. ISBN 9780521666299 – via Google Books.

- Tishkoff, S. A.; et al. (2007). "History of Click-Speaking Populations of Africa Inferred from mtDNA and Y Chromosome Genetic Variation". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (10): 2180–2195. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm155. PMID 17656633.

- Honken, H. and Heine, B. 2010. "The Kxʼa Family: A New Khoisan Genealogy" Archived 2017-08-31 at WebCite. Journal of Asian and African Studies (Tokyo), 79, p. 5–36.

Bibliography

- Barnard, A (1988). ""Kinship, Language and Production: a Conjectural History of Khoisan Social Structure." In". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 58 (1): 29–50. doi:10.2307/1159869.

- Ehret, Christopher. 1986. "Proposals on Khoisan Reconstruction." In African Hunter-Gatherers (International Symposium), edited by Franz Rottland & Rainer Vossen, 105-130. Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, special issue 7.1. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

- Ehret, Christopher. 2003. "Toward reconstructing Proto-South Khoisan." In Mother Tongue 8.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1955. Studies in African Linguistic Classification. New Haven: Compass Publishing Company. (Reprints, with minor corrections, a series of eight articles published in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology from 1949 to 1954.)

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. The Languages of Africa. (Heavily revised version of Greenberg 1955.) Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (From the same publisher: second, revised edition, 1966; third edition, 1970. All three editions simultaneously published at The Hague by Mouton Publishers)

- Güldemann, Tom and Rainer Vossen. 2000. "Khoisan." In African Languages: An Introduction, edited by Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, 99-122. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hastings, Rachel (2001). ""Evidence for the Genetic Unity of Southern Khoesan." In". Cornell Working Papers in Linguistics. 18: 225–245.

- Honken, Henry. 1988. "Phonetic Correspondences among Khoisan Affricates." In New Perspectives on the Study of Khoisan, edited by Rainer Vossen, 47-65. Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 7. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag, 1988.

- Honken, Henry. 1998. "Types of sound correspondence patterns in Khoisan languages." In Language, Identity and Conceptualization among the Khoisan, edited by Mathias Schladt, 171-193. Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung/Research in Khoisan studies 15. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Köhler, O. 1971. "Die Khoe-sprachigen Buschmänner der Kalahari." In Forschungen zur allgemeinen und regionalen Geschichte (Festschrift Kurt Kayser), 373–411. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner.

- Sands, Bonny. 1998. Eastern and Southern African Khoisan: Evaluating Claims of Distant Linguistic Relationships. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Sands, Bonny. 1998. "Comparison and Classification of Khoisan languages." In Language History and Linguistic Description in Africa, edited by Ian Maddieson and Thomas J. Hinnebusch, 75-85. Trenton: Africa World Press.

- Schladt, Mathias (editor). 1998. Language, Identity, and Conceptualization among the Khoisan. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Starostin, George (2003). "A Lexicostatistical Approach towards Reconstructing Proto-Khoisan" (PDF). Mother Tongue. 8: 81–126.

- Starostin, George. 2008. "From modern Khoisan languages to Proto-Khoisan: The Value of Intermediate Reconstructions." (Originally published in Aspects of Comparative Linguistics 3 (2008), 337-470, Moscow: RSUH Publishers.)

- Starostin, George. 2013. Languages of Africa: An attempt at a lexicostatistical classification. Volume I: Methodology. Khoesan Languages. Moscow.

- Traill, Anthony. 1986. "Do the Khoi have a place in the San? New data on Khoisan linguistic relationships." In African Hunter-gatherers (International Symposium), Franz Rottland and Rainer Vossen, 407-430. Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, special issue 7.1. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

- Treis, Yvonne. 1998. "Names of Khoisan languages and Their Variants." In Language, Identity, and Conceptualization Among the Khoisan, edited by Matthias Schladt. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe, 463–503.

- Vossen, Rainer. 1997. Die Khoe-Sprachen. Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Sprachgeschichte Afrikas. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

- Vossen, Rainer. 2013. The Khoesan Languages. Oxon: Routledge.

- Westphal, E.O.J. 1971. "The Click Languages of Southern and Eastern Africa." In Current Trends in Linguistics, Volume 7: Linguistics in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by T.A. Sebeok. Berlin: Mouton, 367–420.

- Winter, J.C. 1981. "Die Khoisan-Familie." In Die Sprachen Afrikas, edited by Bernd Heine, Thilo C. Schadeberg, and Ekkehard Wolff. Hamburg: Helmut Buske, 329–374.