Greenhouse gas

A greenhouse gas (sometimes abbreviated GHG) is a gas that absorbs and emits radiant energy within the thermal infrared range. Greenhouse gases cause the greenhouse effect[1] on planets. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere are water vapor (H

2O), carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), nitrous oxide (N

2O), and ozone (O3). Without greenhouse gases, the average temperature of Earth's surface would be about −18 °C (0 °F),[2] rather than the present average of 15 °C (59 °F).[3][4][5] The atmospheres of Venus, Mars and Titan also contain greenhouse gases.

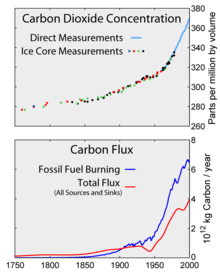

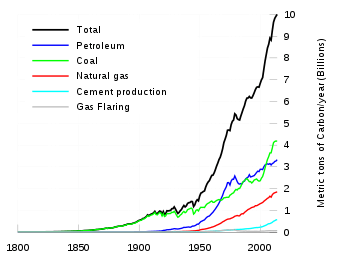

Human activities since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution (around 1750) have produced a 45% increase in the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, from 280 ppm in 1750 to 415 ppm in 2019.[6] The last time the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide was this high was over 3 million years ago. [7] This increase has occurred despite the uptake of more than half of the emissions by various natural "sinks" involved in the carbon cycle.[8][9] The vast majority of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions come from combustion of fossil fuels, principally coal, oil, and natural gas, with additional contributions coming from deforestation, changes in land use, soil erosion and agriculture (including livestock).[10][11] The leading source of anthropogenic methane emissions is animal agriculture, followed by fugitive emissions from gas, oil, coal and other industry, solid waste, wastewater and rice production.[12] Traditional rice cultivation is the second biggest agricultural source of GHG after livestock. Traditional rice production globally accounts for about 1.5% of greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to all aviation emissions. Its source is methane, created by organic matter decomposing underwater in flooded paddies.[13]

At current emission rates, temperatures could increase by 2 °C (3.6°F), which the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) designated as the upper limit to avoid "dangerous" levels, by 2036.[14]

Gases in Earth's atmosphere

Non-greenhouse gases

The major constituents of Earth's atmosphere, nitrogen (N

2)(78%), oxygen (O

2)(21%), and argon (Ar)(0.9%), are not greenhouse gases because molecules containing two atoms of the same element such as N

2 and O

2 have no net change in the distribution of their electrical charges when they vibrate, and monatomic gases such as Ar do not have vibrational modes. Hence they are almost totally unaffected by infrared radiation. Some molecules containing just two atoms of different elements, such as carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen chloride (HCl), do absorb infrared radiation, but these molecules are short-lived in the atmosphere owing to their reactivity or solubility. Therefore, they do not contribute significantly to the greenhouse effect and often are omitted when discussing greenhouse gases.

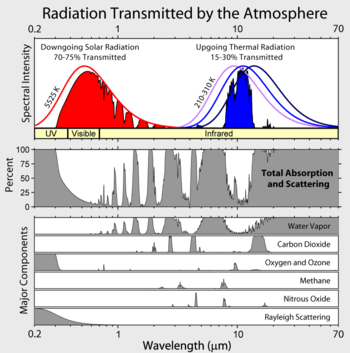

Greenhouse gases

Greenhouse gases are those that absorb and emit infrared radiation in the wavelength range emitted by Earth.[1] Carbon dioxide (0.04%), nitrous oxide, methane and ozone are trace gases that account for almost one tenth of 1% of Earth's atmosphere and have an appreciable greenhouse effect.

In order, the most abundant greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere are:

- Water vapor (H

2O) - Carbon dioxide (CO

2) - Methane (CH

4) - Nitrous oxide (N

2O) - Ozone (O

3) - Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)

- Hydrofluorocarbons (includes HCFCs and HFCs)

Atmospheric concentrations are determined by the balance between sources (emissions of the gas from human activities and natural systems) and sinks (the removal of the gas from the atmosphere by conversion to a different chemical compound or absorption by bodies of water).[15] The proportion of an emission remaining in the atmosphere after a specified time is the "airborne fraction" (AF). The annual airborne fraction is the ratio of the atmospheric increase in a given year to that year's total emissions. As of 2006 the annual airborne fraction for CO

2 was about 0.45. The annual airborne fraction increased at a rate of 0.25 ± 0.21% per year over the period 1959–2006.[16]

Indirect radiative effects

Some gases have indirect radiative effects (whether or not they are greenhouse gases themselves). This happens in two main ways. One way is that when they break down in the atmosphere they produce another greenhouse gas. For example, methane and carbon monoxide (CO) are oxidized to give carbon dioxide (and methane oxidation also produces water vapor). Oxidation of CO to CO

2 directly produces an unambiguous increase in radiative forcing although the reason is subtle. The peak of the thermal IR emission from Earth's surface is very close to a strong vibrational absorption band of CO

2 (wavelength 15 microns, or wavenumber 667 cm−1). On the other hand, the single CO vibrational band only absorbs IR at much shorter wavelengths (4.7 microns, or 2145 cm−1), where the emission of radiant energy from Earth's surface is at least a factor of ten lower. Oxidation of methane to CO

2, which requires reactions with the OH radical, produces an instantaneous reduction in radiative absorption and emission since CO

2 is a weaker greenhouse gas than methane. However, the oxidations of CO and CH

4 are entwined since both consume OH radicals. In any case, the calculation of the total radiative effect includes both direct and indirect forcing.

A second type of indirect effect happens when chemical reactions in the atmosphere involving these gases change the concentrations of greenhouse gases. For example, the destruction of non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) in the atmosphere can produce ozone. The size of the indirect effect can depend strongly on where and when the gas is emitted.[18]

Methane has indirect effects in addition to forming CO

2. The main chemical that reacts with methane in the atmosphere is the hydroxyl radical (OH), thus more methane means that the concentration of OH goes down. Effectively, methane increases its own atmospheric lifetime and therefore its overall radiative effect. The oxidation of methane can produce both ozone and water; and is a major source of water vapor in the normally dry stratosphere. CO and NMVOCs produce CO

2 when they are oxidized. They remove OH from the atmosphere, and this leads to higher concentrations of methane. The surprising effect of this is that the global warming potential of CO is three times that of CO

2.[19] The same process that converts NMVOCs to carbon dioxide can also lead to the formation of tropospheric ozone. Halocarbons have an indirect effect because they destroy stratospheric ozone. Finally, hydrogen can lead to ozone production and CH

4 increases as well as producing stratospheric water vapor.[18]

Contribution of clouds to Earth's greenhouse effect

The major non-gas contributor to Earth's greenhouse effect, clouds, also absorb and emit infrared radiation and thus have an effect on greenhouse gas radiative properties. Clouds are water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the atmosphere.[20][21]

Impacts on the overall greenhouse effect

.png)

The contribution of each gas to the greenhouse effect is determined by the characteristics of that gas, its abundance, and any indirect effects it may cause. For example, the direct radiative effect of a mass of methane is about 84 times stronger than the same mass of carbon dioxide over a 20-year time frame[24] but it is present in much smaller concentrations so that its total direct radiative effect has so far been smaller, in part due to its shorter atmospheric lifetime in the absence of additional carbon sequestration. On the other hand, in addition to its direct radiative impact, methane has a large, indirect radiative effect because it contributes to ozone formation. Shindell et al. (2005)[25] argues that the contribution to climate change from methane is at least double previous estimates as a result of this effect.[26]

When ranked by their direct contribution to the greenhouse effect, the most important are:[20]

| Compound |

Formula |

Concentration in atmosphere[27] (ppm) |

Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water vapor and clouds | H 2O | 10–50,000(A) | 36–72% |

| Carbon dioxide | CO 2 | ~400 | 9–26% |

| Methane | CH 4 | ~1.8 | 4–9% |

| Ozone | O 3 | 2–8(B) | 3–7% |

| notes: (A) Water vapor strongly varies locally[28] | |||

In addition to the main greenhouse gases listed above, other greenhouse gases include sulfur hexafluoride, hydrofluorocarbons and perfluorocarbons (see IPCC list of greenhouse gases). Some greenhouse gases are not often listed. For example, nitrogen trifluoride has a high global warming potential (GWP) but is only present in very small quantities.[29]

Proportion of direct effects at a given moment

It is not possible to state that a certain gas causes an exact percentage of the greenhouse effect. This is because some of the gases absorb and emit radiation at the same frequencies as others, so that the total greenhouse effect is not simply the sum of the influence of each gas. The higher ends of the ranges quoted are for each gas alone; the lower ends account for overlaps with the other gases.[20][21] In addition, some gases, such as methane, are known to have large indirect effects that are still being quantified.[30]

Atmospheric lifetime

Aside from water vapor, which has a residence time of about nine days,[31] major greenhouse gases are well mixed and take many years to leave the atmosphere.[32] Although it is not easy to know with precision how long it takes greenhouse gases to leave the atmosphere, there are estimates for the principal greenhouse gases. Jacob (1999)[33] defines the lifetime of an atmospheric species X in a one-box model as the average time that a molecule of X remains in the box. Mathematically can be defined as the ratio of the mass (in kg) of X in the box to its removal rate, which is the sum of the flow of X out of the box (), chemical loss of X (), and deposition of X () (all in kg/s): .[33] If input of this gas into the box ceased, then after time , its concentration would decrease by about 63%.

The atmospheric lifetime of a species therefore measures the time required to restore equilibrium following a sudden increase or decrease in its concentration in the atmosphere. Individual atoms or molecules may be lost or deposited to sinks such as the soil, the oceans and other waters, or vegetation and other biological systems, reducing the excess to background concentrations. The average time taken to achieve this is the mean lifetime.

Carbon dioxide has a variable atmospheric lifetime, and cannot be specified precisely.[34] The atmospheric lifetime of CO

2 is estimated of the order of 30–95 years.[35]

This figure accounts for CO

2 molecules being removed from the atmosphere by mixing into the ocean, photosynthesis, and other processes. However, this excludes the balancing fluxes of CO

2 into the atmosphere from the geological reservoirs, which have slower characteristic rates.[36] Although more than half of the CO

2 emitted is removed from the atmosphere within a century, some fraction (about 20%) of emitted CO

2 remains in the atmosphere for many thousands of years.[37][38][39] Similar issues apply to other greenhouse gases, many of which have longer mean lifetimes than CO

2, e.g. N2O has a mean atmospheric lifetime of 121 years.[24]

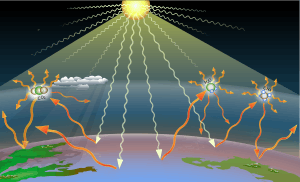

Radiative forcing

Earth absorbs some of the radiant energy received from the sun, reflects some of it as light and reflects or radiates the rest back to space as heat.[40] Earth's surface temperature depends on this balance between incoming and outgoing energy.[40] If this energy balance is shifted, Earth's surface becomes warmer or cooler, leading to a variety of changes in global climate.[40]

A number of natural and man-made mechanisms can affect the global energy balance and force changes in Earth's climate.[40] Greenhouse gases are one such mechanism.[40] Greenhouse gases absorb and emit some of the outgoing energy radiated from Earth's surface, causing that heat to be retained in the lower atmosphere.[40] As explained above, some greenhouse gases remain in the atmosphere for decades or even centuries, and therefore can affect Earth's energy balance over a long period.[40] Radiative forcing quantifies the effect of factors that influence Earth's energy balance, including changes in the concentrations of greenhouse gases.[40] Positive radiative forcing leads to warming by increasing the net incoming energy, whereas negative radiative forcing leads to cooling.[40]

Global warming potential

The global warming potential (GWP) depends on both the efficiency of the molecule as a greenhouse gas and its atmospheric lifetime. GWP is measured relative to the same mass of CO

2 and evaluated for a specific timescale. Thus, if a gas has a high (positive) radiative forcing but also a short lifetime, it will have a large GWP on a 20-year scale but a small one on a 100-year scale. Conversely, if a molecule has a longer atmospheric lifetime than CO

2 its GWP will increase when the timescale is considered. Carbon dioxide is defined to have a GWP of 1 over all time periods.

Methane has an atmospheric lifetime of 12 ± 3 years. The 2007 IPCC report lists the GWP as 72 over a time scale of 20 years, 25 over 100 years and 7.6 over 500 years.[41] A 2014 analysis, however, states that although methane's initial impact is about 100 times greater than that of CO

2, because of the shorter atmospheric lifetime, after six or seven decades, the impact of the two gases is about equal, and from then on methane's relative role continues to decline.[42] The decrease in GWP at longer times is because methane is degraded to water and CO

2 through chemical reactions in the atmosphere.

Examples of the atmospheric lifetime and GWP relative to CO

2 for several greenhouse gases are given in the following table:

| Gas name | Chemical formula | Lifetime (years)[24] |

Global warming potential (GWP) for given time horizon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-yr[24] | 100-yr[24] | 500-yr[41] | |||

| Carbon dioxide | CO 2 | 30–95 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Methane | CH 4 | 12 | 84 | 28 | 7.6 |

| Nitrous oxide | N 2O | 121 | 264 | 265 | 153 |

| CFC-12 | CCl 2F 2 | 100 | 10 800 | 10 200 | 5 200 |

| HCFC-22 | CHClF 2 | 12 | 5 280 | 1 760 | 549 |

| Tetrafluoromethane | CF 4 | 50 000 | 4 880 | 6 630 | 11 200 |

| Hexafluoroethane | C 2F 6 | 10 000 | 8 210 | 11 100 | 18 200 |

| Sulfur hexafluoride | SF 6 | 3 200 | 17 500 | 23 500 | 32 600 |

| Nitrogen trifluoride | NF 3 | 500 | 12 800 | 16 100 | 20 700 |

The use of CFC-12 (except some essential uses) has been phased out due to its ozone depleting properties.[43] The phasing-out of less active HCFC-compounds will be completed in 2030.[44]

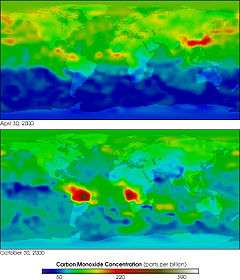

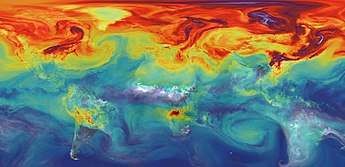

(NASA simulation; 9 November 2015)

Natural and anthropogenic sources

Aside from purely human-produced synthetic halocarbons, most greenhouse gases have both natural and human-caused sources. During the pre-industrial Holocene, concentrations of existing gases were roughly constant, because the large natural sources and sinks roughly balanced. In the industrial era, human activities have added greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, mainly through the burning of fossil fuels and clearing of forests.[47][48]

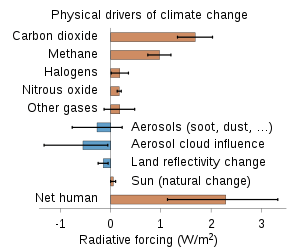

The 2007 Fourth Assessment Report compiled by the IPCC (AR4) noted that "changes in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols, land cover and solar radiation alter the energy balance of the climate system", and concluded that "increases in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations is very likely to have caused most of the increases in global average temperatures since the mid-20th century".[49] In AR4, "most of" is defined as more than 50%.

Abbreviations used in the two tables below: ppm = parts-per-million; ppb = parts-per-billion; ppt = parts-per-trillion; W/m2 = watts per square metre

| Gas | Pre-1750 tropospheric concentration[51] | Recent tropospheric concentration[52] | Absolute increase since 1750 | Percentage increase since 1750 | Increased radiative forcing (W/m2)[53] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon dioxide (CO 2) | 280 ppm[54] | 395.4 ppm[55] | 115.4 ppm | 41.2% | 1.88 |

| Methane (CH 4) | 700 ppb[56] | 1893 ppb /[57][58] 1762 ppb[57] | 1193 ppb / 1062 ppb | 170.4% / 151.7% | 0.49 |

| Nitrous oxide (N 2O) | 270 ppb[53][59] | 326 ppb /[57] 324 ppb[57] | 56 ppb / 54 ppb | 20.7% / 20.0% | 0.17 |

| Tropospheric ozone (O 3) | 237 ppb[51] | 337 ppb[51] | 100 ppb | 42% | 0.4[60] |

| Gas | Recent tropospheric concentration | Increased radiative forcing (W/m2) |

|---|---|---|

| CFC-11 (trichlorofluoromethane) (CCl 3F) | 236 ppt / 234 ppt | 0.061 |

| CFC-12 (CCl 2F 2) | 527 ppt / 527 ppt | 0.169 |

| CFC-113 (Cl 2FC-CClF 2) | 74 ppt / 74 ppt | 0.022 |

| HCFC-22 (CHClF 2) | 231 ppt / 210 ppt | 0.046 |

| HCFC-141b (CH 3CCl 2F) | 24 ppt / 21 ppt | 0.0036 |

| HCFC-142b (CH 3CClF 2) | 23 ppt / 21 ppt | 0.0042 |

| Halon 1211 (CBrClF 2) | 4.1 ppt / 4.0 ppt | 0.0012 |

| Halon 1301 (CBrClF 3) | 3.3 ppt / 3.3 ppt | 0.001 |

| HFC-134a (CH 2FCF 3) | 75 ppt / 64 ppt | 0.0108 |

| Carbon tetrachloride (CCl 4) | 85 ppt / 83 ppt | 0.0143 |

| Sulfur hexafluoride (SF 6) | 7.79 ppt /[61] 7.39 ppt[61] | 0.0043 |

| Other halocarbons | Varies by substance | collectively 0.02 |

| Halocarbons in total | 0.3574 |

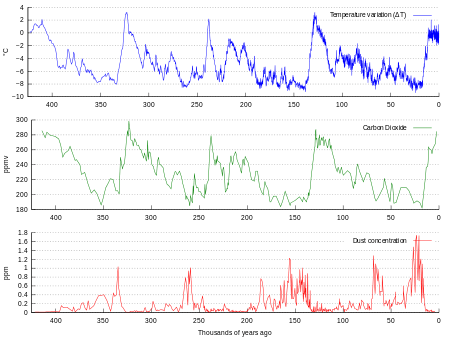

Ice cores provide evidence for greenhouse gas concentration variations over the past 800,000 years (see the following section). Both CO

2 and CH

4 vary between glacial and interglacial phases, and concentrations of these gases correlate strongly with temperature. Direct data does not exist for periods earlier than those represented in the ice core record, a record that indicates CO

2 mole fractions stayed within a range of 180 ppm to 280 ppm throughout the last 800,000 years, until the increase of the last 250 years. However, various proxies and modeling suggests larger variations in past epochs; 500 million years ago CO

2 levels were likely 10 times higher than now.[62] Indeed, higher CO

2 concentrations are thought to have prevailed throughout most of the Phanerozoic eon, with concentrations four to six times current concentrations during the Mesozoic era, and ten to fifteen times current concentrations during the early Palaeozoic era until the middle of the Devonian period, about 400 Ma.[63][64][65] The spread of land plants is thought to have reduced CO

2 concentrations during the late Devonian, and plant activities as both sources and sinks of CO

2 have since been important in providing stabilising feedbacks.[66]

Earlier still, a 200-million year period of intermittent, widespread glaciation extending close to the equator (Snowball Earth) appears to have been ended suddenly, about 550 Ma, by a colossal volcanic outgassing that raised the CO

2 concentration of the atmosphere abruptly to 12%, about 350 times modern levels, causing extreme greenhouse conditions and carbonate deposition as limestone at the rate of about 1 mm per day.[67] This episode marked the close of the Precambrian eon, and was succeeded by the generally warmer conditions of the Phanerozoic, during which multicellular animal and plant life evolved. No volcanic carbon dioxide emission of comparable scale has occurred since. In the modern era, emissions to the atmosphere from volcanoes are approximately 0.645 billion tonnes of CO

2 per year, whereas humans contribute 29 billion tonnes of CO

2 each year.[68][67][69][70]

Ice cores

Measurements from Antarctic ice cores

show that before industrial emissions started atmospheric CO

2 mole fractions were about 280 parts per million (ppm), and stayed between 260 and 280 during the preceding ten thousand years.[71] Carbon dioxide mole fractions in the atmosphere have gone up by approximately 35 percent since the 1900s, rising from 280 parts per million by volume to 387 parts per million in 2009. One study using evidence from stomata of fossilized leaves suggests greater variability, with carbon dioxide mole fractions above 300 ppm during the period seven to ten thousand years ago,[72] though others have argued that these findings more likely reflect calibration or contamination problems rather than actual CO

2 variability.[73][74] Because of the way air is trapped in ice (pores in the ice close off slowly to form bubbles deep within the firn) and the time period represented in each ice sample analyzed, these figures represent averages of atmospheric concentrations of up to a few centuries rather than annual or decadal levels.

Changes since the Industrial Revolution

2.

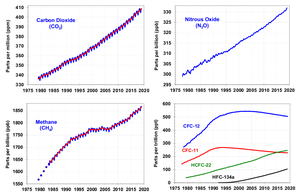

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the concentrations of many of the greenhouse gases have increased. For example, the mole fraction of carbon dioxide has increased from 280 ppm to 415 ppm, or 120 ppm over modern pre-industrial levels. The first 30 ppm increase took place in about 200 years, from the start of the Industrial Revolution to 1958; however the next 90 ppm increase took place within 56 years, from 1958 to 2014.[75][76]

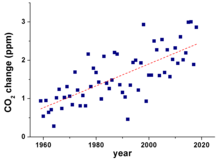

Recent data also shows that the concentration is increasing at a higher rate. In the 1960s, the average annual increase was only 37% of what it was in 2000 through 2007.[77]

Total cumulative emissions from 1870 to 2017 were 425±20 GtC (1539 GtCO2) from fossil fuels and industry, and 180±60 GtC (660 GtCO2) from land use change. Land-use change, such as deforestation, caused about 31% of cumulative emissions over 1870–2017, coal 32%, oil 25%, and gas 10%.[78]

Today, the stock of carbon in the atmosphere increases by more than 3 million tonnes per annum (0.04%) compared with the existing stock. This increase is the result of human activities by burning fossil fuels, deforestation and forest degradation in tropical and boreal regions.[79]

The other greenhouse gases produced from human activity show similar increases in both amount and rate of increase. Many observations are available online in a variety of Atmospheric Chemistry Observational Databases.

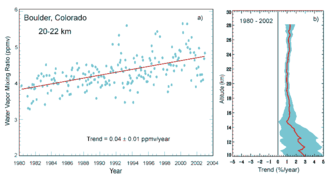

Role of water vapor

Water vapor accounts for the largest percentage of the greenhouse effect, between 36% and 66% for clear sky conditions and between 66% and 85% when including clouds.[21] Water vapor concentrations fluctuate regionally, but human activity does not directly affect water vapor concentrations except at local scales, such as near irrigated fields. Indirectly, human activity that increases global temperatures will increase water vapor concentrations, a process known as water vapor feedback.[80] The atmospheric concentration of vapor is highly variable and depends largely on temperature, from less than 0.01% in extremely cold regions up to 3% by mass in saturated air at about 32 °C.[81] (See Relative humidity#other important facts.)

The average residence time of a water molecule in the atmosphere is only about nine days, compared to years or centuries for other greenhouse gases such as CH

4 and CO

2.[82] Water vapor responds to and amplifies effects of the other greenhouse gases. The Clausius–Clapeyron relation establishes that more water vapor will be present per unit volume at elevated temperatures. This and other basic principles indicate that warming associated with increased concentrations of the other greenhouse gases also will increase the concentration of water vapor (assuming that the relative humidity remains approximately constant; modeling and observational studies find that this is indeed so). Because water vapor is a greenhouse gas, this results in further warming and so is a "positive feedback" that amplifies the original warming. Eventually other earth processes offset these positive feedbacks, stabilizing the global temperature at a new equilibrium and preventing the loss of Earth's water through a Venus-like runaway greenhouse effect.[80]

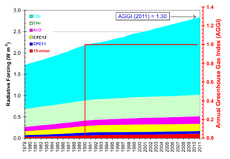

Anthropogenic greenhouse gases

.png)

Since about 1750 human activity has increased the concentration of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Measured atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide are currently 100 ppm higher than pre-industrial levels.[85] Natural sources of carbon dioxide are more than 20 times greater than sources due to human activity,[86] but over periods longer than a few years natural sources are closely balanced by natural sinks, mainly photosynthesis of carbon compounds by plants and marine plankton. As a result of this balance, the atmospheric mole fraction of carbon dioxide remained between 260 and 280 parts per million for the 10,000 years between the end of the last glacial maximum and the start of the industrial era.[87]

It is likely that anthropogenic (i.e., human-induced) warming, such as that due to elevated greenhouse gas levels, has had a discernible influence on many physical and biological systems.[88] Future warming is projected to have a range of impacts, including sea level rise,[89] increased frequencies and severities of some extreme weather events,[89] loss of biodiversity,[90] and regional changes in agricultural productivity.[90]

The main sources of greenhouse gases due to human activity are:

- burning of fossil fuels and deforestation leading to higher carbon dioxide concentrations in the air. Land use change (mainly deforestation in the tropics) account for up to one third of total anthropogenic CO

2 emissions.[87] - livestock enteric fermentation and manure management,[91] paddy rice farming, land use and wetland changes, man-made lakes,[92] pipeline losses, and covered vented landfill emissions leading to higher methane atmospheric concentrations. Many of the newer style fully vented septic systems that enhance and target the fermentation process also are sources of atmospheric methane.

- use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in refrigeration systems, and use of CFCs and halons in fire suppression systems and manufacturing processes.

- agricultural activities, including the use of fertilizers, that lead to higher nitrous oxide (N

2O) concentrations.

| Food Types | Greenhouse Gas Emissions (g CO2-Ceq per g protein) |

|---|---|

| Ruminant Meat | 62 |

| Recirculating Aquaculture | 30 |

| Trawling Fishery | 26 |

| Non-recirculating Aquaculture | 12 |

| Pork | 10 |

| Poultry | 10 |

| Dairy | 9.1 |

| Non-trawling Fishery | 8.6 |

| Eggs | 6.8 |

| Starchy Roots | 1.7 |

| Wheat | 1.2 |

| Maize | 1.2 |

| Legumes | 0.25 |

The seven sources of CO

2 from fossil fuel combustion are (with percentage contributions for 2000–2004):[94]

This list needs updating, as it uses an out of date source.

- Liquid fuels (e.g., gasoline, fuel oil): 36%

- Solid fuels (e.g., coal): 35%

- Gaseous fuels (e.g., natural gas): 20%

- Cement production:3 %

- Flaring gas industrially and at wells: 1%

- Non-fuel hydrocarbons:1%

- "International bunker fuels" of transport not included in national inventories: 4 %

Carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide (N

2O) and three groups of fluorinated gases (sulfur hexafluoride (SF

6), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and perfluorocarbons (PFCs)) are the major anthropogenic greenhouse gases,[95]:147[96] and are regulated under the Kyoto Protocol international treaty, which came into force in 2005.[97] Emissions limitations specified in the Kyoto Protocol expired in 2012.[97] The Cancún agreement, agreed on in 2010, includes voluntary pledges made by 76 countries to control emissions.[98] At the time of the agreement, these 76 countries were collectively responsible for 85% of annual global emissions.[98]

Although CFCs are greenhouse gases, they are regulated by the Montreal Protocol, which was motivated by CFCs' contribution to ozone depletion rather than by their contribution to global warming. Note that ozone depletion has only a minor role in greenhouse warming, though the two processes often are confused in the media. On 15 October 2016, negotiators from over 170 nations meeting at the summit of the United Nations Environment Programme reached a legally binding accord to phase out hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) in an amendment to the Montreal Protocol.[99][100][101]

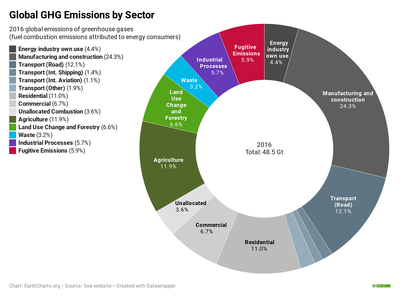

Greenhouse gases emissions by sector

Global greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed to different sectors of the economy. This provides a picture of the varying contributions of different types of economic activity to global warming, and helps in understanding the changes required to mitigate climate change.

Manmade greenhouse gas emissions can be divided into those that arise from the combustion of fuels to produce energy, and those generated by other processes. Around two thirds of greenhouse gas emissions arise from the combustion of fuels.[103]

Energy may be produced at the point of consumption, or by a generator for consumption by others. Thus emissions arising from energy production may be categorised according to where they are emitted, or where the resulting energy is consumed. If emissions are attributed at the point of production, then electricity generators contribute about 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[104] If these emissions are attributed to the final consumer then 24% of total emissions arise from manufacturing and construction, 17% from transportation, 11% from domestic consumers, and 7% from commercial consumers.[105] Around 4% of emissions arise from the energy consumed by the energy and fuel industry itself.

The remaining third of emissions arise from processes other than energy production. 12% of total emissions arise from agriculture, 7% from land use change and forestry, 6% from industrial processes, and 3% from waste[103] . Around 6% of emissions are fugitive emissions, which are waste gases released by the extraction of fossil fuels.

Electricity generation

Electricity generation emits over a quarter of global greenhouse gases.[106] Coal-fired power stations are the single largest emitter, with over 10 Gt CO

2 in 2018.[107] Although much less polluting than coal plants, natural gas-fired power plants are also major emitters.[108]

Tourism

According to UNEP, global tourism is closely linked to climate change. Tourism is a significant contributor to the increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Tourism accounts for about 50% of traffic movements. Rapidly expanding air traffic contributes about 2.5% of the production of CO

2. The number of international travelers is expected to increase from 594 million in 1996 to 1.6 billion by 2020, adding greatly to the problem unless steps are taken to reduce emissions.[109]

Trucking and haulage

The trucking and haulage industry plays a part in production of CO

2, contributing around 20% of the UK's total carbon emissions a year, with only the energy industry having a larger impact at around 39%.[110]

Average carbon emissions within the haulage industry are falling—in the thirty-year period from 1977 to 2007, the carbon emissions associated with a 200-mile journey fell by 21 percent; NOx emissions are also down 87 percent, whereas journey times have fallen by around a third.[111]

Plastic

Plastic is produced mainly from fossil fuels. Plastic manufacturing is estimated to use 8 percent of yearly global oil production. The EPA estimates as many as five mass units of carbon dioxide are emitted for each mass unit of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) produced—the type of plastic most commonly used for beverage bottles,[112] the transportation produce greenhouse gases also.[113] Plastic waste emits carbon dioxide when it degrades. In 2018 research claimed that some of the most common plastics in the environment release the greenhouse gases methane and ethylene when exposed to sunlight in an amount that can affect the earth climate.[114][115]

From the other side, if it is placed in a landfill, it becomes a carbon sink[116] although biodegradable plastics have caused methane emissions. [117] Due to the lightness of plastic versus glass or metal, plastic may reduce energy consumption. For example, packaging beverages in PET plastic rather than glass or metal is estimated to save 52% in transportation energy, if the glass or metal package is single-use, of course.

In 2019 a new report "Plastic and Climate" was published. According to the report plastic will contribute greenhouse gases in the equivalent of 850 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere in 2019. In current trend, annual emissions will grow to 1.34 billion tonnes by 2030. By 2050 plastic could emit 56 billion tonnes of Greenhouse gas emissions, as much as 14 percent of the Earth's remaining carbon budget.[118] The report says that only solutions which involve a reduction in consumption can solve the problem, while others like biodegradable plastic, ocean cleanup, using renewable energy in plastic industry can do little, and in some cases may even worsen it.[119]

Pharmaceutical industry

The pharmaceutical industry emitted 52 megatonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in 2015. This is more than the automotive sector. However this analysis used the combined emissions of conglomerates which produce pharmaceuticals as well as other products.[120]

Regional and national attribution of emissions

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), GHG emissions in the United States can be traced from different sectors.

There are several ways of measuring greenhouse gas emissions, for example, see World Bank (2010)[121]:362 for tables of national emissions data. Some variables that have been reported[122] include:

- Definition of measurement boundaries: Emissions can be attributed geographically, to the area where they were emitted (the territory principle) or by the activity principle to the territory produced the emissions. These two principles result in different totals when measuring, for example, electricity importation from one country to another, or emissions at an international airport.

- Time horizon of different gases: Contribution of a given greenhouse gas is reported as a CO

2 equivalent. The calculation to determine this takes into account how long that gas remains in the atmosphere. This is not always known accurately and calculations must be regularly updated to reflect new information. - What sectors are included in the calculation (e.g., energy industries, industrial processes, agriculture etc.): There is often a conflict between transparency and availability of data.

- The measurement protocol itself: This may be via direct measurement or estimation. The four main methods are the emission factor-based method, mass balance method, predictive emissions monitoring systems, and continuous emissions monitoring systems. These methods differ in accuracy, cost, and usability.

These measures are sometimes used by countries to assert various policy/ethical positions on climate change (Banuri et al., 1996, p. 94).[123] The use of different measures leads to a lack of comparability, which is problematic when monitoring progress towards targets. There are arguments for the adoption of a common measurement tool, or at least the development of communication between different tools.[122]

Emissions may be measured over long time periods. This measurement type is called historical or cumulative emissions. Cumulative emissions give some indication of who is responsible for the build-up in the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases (IEA, 2007, p. 199).[124]

The national accounts balance would be positively related to carbon emissions. The national accounts balance shows the difference between exports and imports. For many richer nations, such as the United States, the accounts balance is negative because more goods are imported than they are exported. This is mostly due to the fact that it is cheaper to produce goods outside of developed countries, leading the economies of developed countries to become increasingly dependent on services and not goods. We believed that a positive accounts balance would means that more production was occurring in a country, so more factories working would increase carbon emission levels.[125]

Emissions may also be measured across shorter time periods. Emissions changes may, for example, be measured against a base year of 1990. 1990 was used in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as the base year for emissions, and is also used in the Kyoto Protocol (some gases are also measured from the year 1995).[95]:146, 149 A country's emissions may also be reported as a proportion of global emissions for a particular year.

Another measurement is of per capita emissions. This divides a country's total annual emissions by its mid-year population.[121]:370 Per capita emissions may be based on historical or annual emissions (Banuri et al., 1996, pp. 106–07).[123]

While cities are sometimes considered to be disproportionate contributors to emissions, per-capita emissions tend to be lower for cities than the averages in their countries.[126]

From land-use change

Land-use change, e.g., the clearing of forests for agricultural use, can affect the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere by altering how much carbon flows out of the atmosphere into carbon sinks.[127] Accounting for land-use change can be understood as an attempt to measure "net" emissions, i.e., gross emissions from all sources minus the removal of emissions from the atmosphere by carbon sinks (Banuri et al., 1996, pp. 92–93).[123]

There are substantial uncertainties in the measurement of net carbon emissions.[128] Additionally, there is controversy over how carbon sinks should be allocated between different regions and over time (Banuri et al., 1996, p. 93).[123] For instance, concentrating on more recent changes in carbon sinks is likely to favour those regions that have deforested earlier, e.g., Europe.

Greenhouse gas intensity

Greenhouse gas intensity is a ratio between greenhouse gas emissions and another metric, e.g., gross domestic product (GDP) or energy use. The terms "carbon intensity" and "emissions intensity" are also sometimes used.[129] Emission intensities may be calculated using market exchange rates (MER) or purchasing power parity (PPP) (Banuri et al., 1996, p. 96).[123] Calculations based on MER show large differences in intensities between developed and developing countries, whereas calculations based on PPP show smaller differences.

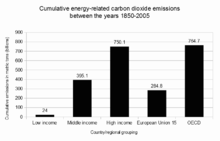

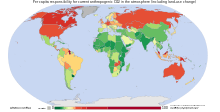

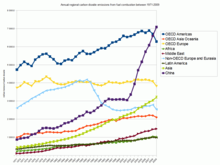

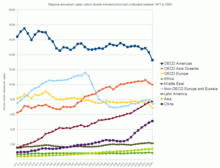

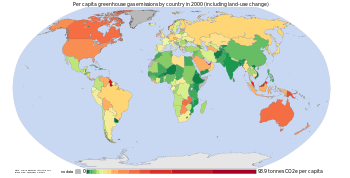

Cumulative and historical emissions

2 emissions between the years 1850–2005 grouped into low-income, middle-income, high-income, the EU-15, and the OECD countries.

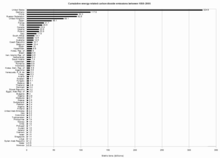

2 emissions between the years 1850–2005 for individual countries.

2 emissions by country. Cumulative emissions include land use change, and are measured between the years 1950 and 2000.

2 emissions from fuel combustion between 1971 and 2009.

2 emissions from fuel combustion between 1971 and 2009.

Cumulative anthropogenic (i.e., human-emitted) emissions of CO

2 from fossil fuel use are a major cause of global warming,[130] and give some indication of which countries have contributed most to human-induced climate change.[131]:15 Overall, developed countries accounted for 83.8% of industrial CO

2 emissions over this time period, and 67.8% of total CO

2 emissions. Developing countries accounted for industrial CO

2 emissions of 16.2% over this time period, and 32.2% of total CO

2 emissions. The estimate of total CO

2 emissions includes biotic carbon emissions, mainly from deforestation. Banuri et al. (1996, p. 94)[123] calculated per capita cumulative emissions based on then-current population. The ratio in per capita emissions between industrialized countries and developing countries was estimated at more than 10 to 1.

Including biotic emissions brings about the same controversy mentioned earlier regarding carbon sinks and land-use change (Banuri et al., 1996, pp. 93–94).[123] The actual calculation of net emissions is very complex, and is affected by how carbon sinks are allocated between regions and the dynamics of the climate system.

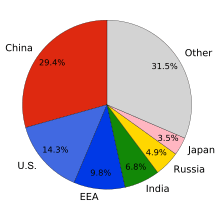

Non-OECD countries accounted for 42% of cumulative energy-related CO

2 emissions between 1890 and 2007.[132]:179–80 Over this time period, the US accounted for 28% of emissions; the EU, 23%; Russia, 11%; China, 9%; other OECD countries, 5%; Japan, 4%; India, 3%; and the rest of the world, 18%.[132]:179–80

Changes since a particular base year

Between 1970 and 2004, global growth in annual CO

2 emissions was driven by North America, Asia, and the Middle East.[133] The sharp acceleration in CO

2 emissions since 2000 to more than a 3% increase per year (more than 2 ppm per year) from 1.1% per year during the 1990s is attributable to the lapse of formerly declining trends in carbon intensity of both developing and developed nations. China was responsible for most of global growth in emissions during this period. Localised plummeting emissions associated with the collapse of the Soviet Union have been followed by slow emissions growth in this region due to more efficient energy use, made necessary by the increasing proportion of it that is exported.[94] In comparison, methane has not increased appreciably, and N

2O by 0.25% y−1.

Using different base years for measuring emissions has an effect on estimates of national contributions to global warming.[131]:17–18[134] This can be calculated by dividing a country's highest contribution to global warming starting from a particular base year, by that country's minimum contribution to global warming starting from a particular base year. Choosing between base years of 1750, 1900, 1950, and 1990 has a significant effect for most countries.[131]:17–18 Within the G8 group of countries, it is most significant for the UK, France and Germany. These countries have a long history of CO

2 emissions (see the section on Cumulative and historical emissions).

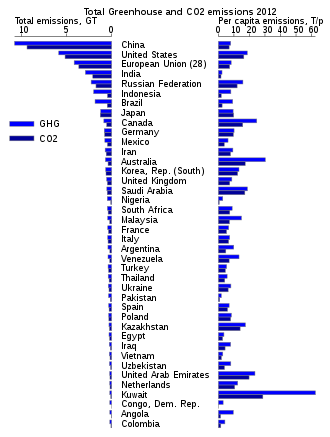

Annual emissions

Annual per capita emissions in the industrialized countries are typically as much as ten times the average in developing countries.[95]:144 Due to China's fast economic development, its annual per capita emissions are quickly approaching the levels of those in the Annex I group of the Kyoto Protocol (i.e., the developed countries excluding the US).[135] Other countries with fast growing emissions are South Korea, Iran, and Australia (which apart from the oil rich Persian Gulf states, now has the highest percapita emission rate in the world). On the other hand, annual per capita emissions of the EU-15 and the US are gradually decreasing over time.[135] Emissions in Russia and Ukraine have decreased fastest since 1990 due to economic restructuring in these countries.[136]

Energy statistics for fast growing economies are less accurate than those for the industrialized countries. For China's annual emissions in 2008, the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency estimated an uncertainty range of about 10%.[135]

The greenhouse gas footprint refers to the emissions resulting from the creation of products or services. It is more comprehensive than the commonly used carbon footprint, which measures only carbon dioxide, one of many greenhouse gases.

2015 was the first year to see both total global economic growth and a reduction of carbon emissions.[137]

Top emitter countries

Annual

In 2009, the annual top ten emitting countries accounted for about two-thirds of the world's annual energy-related CO

2 emissions.[138]

| Country | % of global total annual emissions |

Total 2017 CO2 Emissions (kilotons) [140] | Tonnes of GHG per capita[141] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 29.3 | 10877217 | 7.7 | |

| 13.8 | 5107393 | 15.7 | |

| 6.6 | 2454773 | 1.8 | |

| 4.8 | 1764865 | 12.2 | |

| 3.6 | 1320776 | 10.4 | |

| 2.1 | 796528 | 9.7 | |

| South Korea | 1.8 | 673323 | 13.2 |

| Iran | 1.8 | 671450 | 8.2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1.7 | 638761 | 19.3 |

| Canada | 1.7 | 617300 | 16.9 |

Embedded emissions

One way of attributing greenhouse gas emissions is to measure the embedded emissions (also referred to as "embodied emissions") of goods that are being consumed. Emissions are usually measured according to production, rather than consumption.[142] For example, in the main international treaty on climate change (the UNFCCC), countries report on emissions produced within their borders, e.g., the emissions produced from burning fossil fuels.[132]:179[143]:1 Under a production-based accounting of emissions, embedded emissions on imported goods are attributed to the exporting, rather than the importing, country. Under a consumption-based accounting of emissions, embedded emissions on imported goods are attributed to the importing country, rather than the exporting, country.

Davis and Caldeira (2010)[143]:4 found that a substantial proportion of CO

2 emissions are traded internationally. The net effect of trade was to export emissions from China and other emerging markets to consumers in the US, Japan, and Western Europe. Based on annual emissions data from the year 2004, and on a per-capita consumption basis, the top-5 emitting countries were found to be (in tCO

2 per person, per year): Luxembourg (34.7), the US (22.0), Singapore (20.2), Australia (16.7), and Canada (16.6).[143]:5 Carbon Trust research revealed that approximately 25% of all CO

2 emissions from human activities 'flow' (i.e., are imported or exported) from one country to another. Major developed economies were found to be typically net importers of embodied carbon emissions—with UK consumption emissions 34% higher than production emissions, and Germany (29%), Japan (19%) and the US (13%) also significant net importers of embodied emissions.[144]

Effect of policy

Governments have taken action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate climate change. Assessments of policy effectiveness have included work by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,[145] International Energy Agency,[146][147] and United Nations Environment Programme.[148] Policies implemented by governments have included[149][150][151] national and regional targets to reduce emissions, promoting energy efficiency, and support for a renewable energy transition such as Solar energy as an effective use of renewable energy because solar uses energy from the sun and does not release pollutants into the air.

Countries and regions listed in Annex I of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (i.e., the OECD and former planned economies of the Soviet Union) are required to submit periodic assessments to the UNFCCC of actions they are taking to address climate change.[151]:3 Analysis by the UNFCCC (2011)[151]:8 suggested that policies and measures undertaken by Annex I Parties may have produced emission savings of 1.5 thousand Tg CO

2-eq in the year 2010, with most savings made in the energy sector. The projected emissions saving of 1.5 thousand Tg CO

2-eq is measured against a hypothetical "baseline" of Annex I emissions, i.e., projected Annex I emissions in the absence of policies and measures. The total projected Annex I saving of 1.5 thousand CO

2-eq does not include emissions savings in seven of the Annex I Parties.[151]:8

Projections

A wide range of projections of future emissions have been produced.[152] Rogner et al. (2007)[153] assessed the scientific literature on greenhouse gas projections. Rogner et al. (2007)[154] concluded that unless energy policies changed substantially, the world would continue to depend on fossil fuels until 2025–2030. Projections suggest that more than 80% of the world's energy will come from fossil fuels. This conclusion was based on "much evidence" and "high agreement" in the literature.[154] Projected annual energy-related CO

2 emissions in 2030 were 40–110% higher than in 2000, with two-thirds of the increase originating in developing countries.[154] Projected annual per capita emissions in developed country regions remained substantially lower (2.8–5.1 tonnes CO

2) than those in developed country regions (9.6–15.1 tonnes CO

2).[155] Projections consistently showed increase in annual world emissions of "Kyoto" gases,[156] measured in CO

2-equivalent) of 25–90% by 2030, compared to 2000.[154]

Relative CO

2 emission from various fuels

2 emission from various fuels

One liter of gasoline, when used as a fuel, produces 2.32 kg (about 1300 liters or 1.3 cubic meters) of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. One US gallon produces 19.4 lb (1,291.5 gallons or 172.65 cubic feet).[157][158][159]

| Fuel name | CO 2 emitted (lbs/106 Btu) |

CO 2 emitted (g/MJ) |

CO 2 emitted (g/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural gas | 117 | 50.30 | 181.08 |

| Liquefied petroleum gas | 139 | 59.76 | 215.14 |

| Propane | 139 | 59.76 | 215.14 |

| Aviation gasoline | 153 | 65.78 | 236.81 |

| Automobile gasoline | 156 | 67.07 | 241.45 |

| Kerosene | 159 | 68.36 | 246.10 |

| Fuel oil | 161 | 69.22 | 249.19 |

| Tires/tire derived fuel | 189 | 81.26 | 292.54 |

| Wood and wood waste | 195 | 83.83 | 301.79 |

| Coal (bituminous) | 205 | 88.13 | 317.27 |

| Coal (sub-bituminous) | 213 | 91.57 | 329.65 |

| Coal (lignite) | 215 | 92.43 | 332.75 |

| Petroleum coke | 225 | 96.73 | 348.23 |

| Tar-sand bitumen | |||

| Coal (anthracite) | 227 | 97.59 | 351.32 |

Life-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions of energy sources

A 2011 IPCC report included a literature review of numerous energy sources' total life cycle CO

2 emissions. Below are the CO

2 emission values that fell at the 50th percentile of all studies surveyed.[161]

| Technology | Description | 50th percentile (g CO 2/kWhe) |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroelectric | reservoir | 4 |

| Ocean Energy | wave and tidal | 8 |

| Wind | onshore | 12 |

| Nuclear | various generation II reactor types | 16 |

| Biomass | various | 18 |

| Solar thermal | parabolic trough | 22 |

| Geothermal | hot dry rock | 45 |

| Solar PV | Polycrystalline silicon | 46 |

| Natural gas | various combined cycle turbines without scrubbing | 469 |

| Coal | various generator types without scrubbing | 1001 |

Removal from the atmosphere

Natural processes

Greenhouse gases can be removed from the atmosphere by various processes, as a consequence of:

- a physical change (condensation and precipitation remove water vapor from the atmosphere).

- a chemical reaction within the atmosphere. For example, methane is oxidized by reaction with naturally occurring hydroxyl radical, OH· and degraded to CO

2 and water vapor (CO

2 from the oxidation of methane is not included in the methane Global warming potential). Other chemical reactions include solution and solid phase chemistry occurring in atmospheric aerosols. - a physical exchange between the atmosphere and the other components of the planet. An example is the mixing of atmospheric gases into the oceans.

- a chemical change at the interface between the atmosphere and the other components of the planet. This is the case for CO

2, which is reduced by photosynthesis of plants, and which, after dissolving in the oceans, reacts to form carbonic acid and bicarbonate and carbonate ions (see ocean acidification). - a photochemical change. Halocarbons are dissociated by UV light releasing Cl· and F· as free radicals in the stratosphere with harmful effects on ozone (halocarbons are generally too stable to disappear by chemical reaction in the atmosphere).

Negative emissions

A number of technologies remove greenhouse gases emissions from the atmosphere. Most widely analysed are those that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, either to geologic formations such as bio-energy with carbon capture and storage and carbon dioxide air capture,[162] or to the soil as in the case with biochar.[162] The IPCC has pointed out that many long-term climate scenario models require large-scale manmade negative emissions to avoid serious climate change.[163]

History of scientific research

In the late 19th century scientists experimentally discovered that N

2 and O

2 do not absorb infrared radiation (called, at that time, "dark radiation"), while water (both as true vapor and condensed in the form of microscopic droplets suspended in clouds) and CO

2 and other poly-atomic gaseous molecules do absorb infrared radiation. In the early 20th century researchers realized that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere made Earth's overall temperature higher than it would be without them. During the late 20th century, a scientific consensus evolved that increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere cause a substantial rise in global temperatures and changes to other parts of the climate system,[164] with consequences for the environment and for human health.

See also

- Attribution of recent climate change

- Cap and Trade

- Carbon accounting

- Carbon credit

- Carbon emissions reporting

- Carbon neutrality

- Carbon offset

- Carbon tax

- Deforestation and climate change

- Emission standard

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Greenhouse debt

- Hydrogen economy

- Integrated Carbon Observation System

- List of countries by electricity production from renewable sources

- List of international environmental agreements

- Low-carbon economy

- Mobile source air pollution

- Paris Agreement

- Perfluorotributylamine

- Physical properties of greenhouse gases

- Sustainability measurement

- Top contributors to greenhouse gas emissions

- VOC Exempt solvents

- Waste management

- World energy consumption

- Zero-emissions vehicle

References

- "IPCC AR4 SYR Appendix Glossary" (PDF). Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "NASA GISS: Science Briefs: Greenhouse Gases: Refining the Role of Carbon Dioxide". www.giss.nasa.gov. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Karl TR, Trenberth KE (2003). "Modern global climate change". Science. 302 (5651): 1719–23. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1719K. doi:10.1126/science.1090228. PMID 14657489.

- Le Treut H.; Somerville R.; Cubasch U.; Ding Y.; Mauritzen C.; Mokssit A.; Peterson T.; Prather M. Historical overview of climate change science (PDF). Retrieved 14 December 2008. in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007)

- "NASA Science Mission Directorate article on the water cycle". Nasascience.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- "CO2 in the atmosphere just exceeded 415 parts per million for the first time in human history". Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide | NOAA Climate.gov". www.climate.gov. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Frequently asked global change questions". Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center.

- ESRL Web Team (14 January 2008). "Trends in carbon dioxide". Esrl.noaa.gov. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- "Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

The burning of coal, natural gas, and oil for electricity and heat is the largest single source of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- "AR4 SYR Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers – 2 Causes of change". ipcc.ch. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- https://www.globalmethane.org/documents/gmi-mitigation-factsheet.pdf

- Reed, John (25 June 2020). "Thai rice farmers step up to tackle carbon footprint". Financial Times. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Mann, Michael E. (1 April 2014). "Earth Will Cross the Climate Danger Threshold by 2036". Scientific American. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- "FAQ 7.1". p. 14. in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007)

- Canadell, J.G.; Le Quere, C.; Raupach, M.R.; Field, C.B.; Buitenhuis, E.T.; Ciais, P.; Conway, T.J.; Gillett, N.P.; Houghton, R.A.; Marland, G. (2007). "Contributions to accelerating atmospheric CO

2 growth from economic activity, carbon intensity, and efficiency of natural sinks". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104 (47): 18866–70. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10418866C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702737104. PMC 2141868. PMID 17962418. - "The Chemistry of Earth's Atmosphere". Earth Observatory. NASA. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008.

- Forster, P.; et al. (2007). "2.10.3 Indirect GWPs". Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- MacCarty, N. "Laboratory Comparison of the Global-Warming Potential of Six Categories of Biomass Cooking Stoves" (PDF). Approvecho Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2013.

- Kiehl, J.T.; Kevin E. Trenberth (1997). "Earth's annual global mean energy budget". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 78 (2): 197–208. Bibcode:1997BAMS...78..197K. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<0197:EAGMEB>2.0.CO;2.

- "Water vapour: feedback or forcing?". RealClimate. 6 April 2005. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- Schmidt, G.A.; R. Ruedy; R.L. Miller; A.A. Lacis (2010), "The attribution of the present-day total greenhouse effect" (PDF), J. Geophys. Res., 115 (D20), pp. D20106, Bibcode:2010JGRD..11520106S, doi:10.1029/2010JD014287, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2011, D20106. Web page

- Lacis, A. (October 2010), NASA GISS: CO2: The Thermostat that Controls Earth's Temperature, New York: NASA GISS

- "Appendix 8.A" (PDF). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report. p. 731.

- Shindell, Drew T. (2005). "An emissions-based view of climate forcing by methane and tropospheric ozone". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (4): L04803. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..32.4803S. doi:10.1029/2004GL021900.

- "Methane's Impacts on Climate Change May Be Twice Previous Estimates". Nasa.gov. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- "Climate Change Indicators: Atmospheric Concentrations of Greenhouse Gases". Climate Change Indicators. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- Wallace, John M. and Peter V. Hobbs. Atmospheric Science; An Introductory Survey. Elsevier. Second Edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0127329512. Chapter 1

- Prather, Michael J.; J Hsu (2008). "NF

3, the greenhouse gas missing from Kyoto". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (12): L12810. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3512810P. doi:10.1029/2008GL034542. - Isaksen, Ivar S.A.; Michael Gauss; Gunnar Myhre; Katey M. Walter Anthony; Carolyn Ruppel (20 April 2011). "Strong atmospheric chemistry feedback to climate warming from Arctic methane emissions" (PDF). Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 25 (2): n/a. Bibcode:2011GBioC..25.2002I. doi:10.1029/2010GB003845. hdl:1912/4553. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "AGU Water Vapor in the Climate System". Eso.org. 27 April 1995. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Betts (2001). "6.3 Well-mixed Greenhouse Gases". Chapter 6 Radiative Forcing of Climate Change. Working Group I: The Scientific Basis IPCC Third Assessment Report – Climate Change 2001. UNEP/GRID-Arendal – Publications. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- Jacob, Daniel (1999). Introduction to atmospheric chemistry. Princeton University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0691001852. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011.

- "How long will global warming last?". RealClimate. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Jacobson, M.Z. (2005). "Correction to "Control of fossil-fuel particulate black carbon and organic matter, possibly the most effective method of slowing global warming."". J. Geophys. Res. 110: D14105. Bibcode:2005JGRD..11014105J. doi:10.1029/2005JD005888.

- Archer, David (2009). "Atmospheric lifetime of fossil fuel carbon dioxide". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 37: 117–34. Bibcode:2009AREPS..37..117A. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100206.

- "Frequently Asked Question 10.3: If emissions of greenhouse gases are reduced, how quickly do their concentrations in the atmosphere decrease?". Global Climate Projections. Retrieved 1 June 2011. in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007)

- See also: Archer, David (2005). "Fate of fossil fuel CO

2 in geologic time" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 110 (C9): C09S05.1–6. Bibcode:2005JGRC..11009S05A. doi:10.1029/2004JC002625. Retrieved 27 July 2007. - See also: Caldeira, Ken; Wickett, Michael E. (2005). "Ocean model predictions of chemistry changes from carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere and ocean" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 110 (C9): C09S04.1–12. Bibcode:2005JGRC..11009S04C. doi:10.1029/2004JC002671. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- Edited quote from public-domain source: "Climate Change Indicators in the United States". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2010. Greenhouse Gases: Figure 1. The Annual Greenhouse Gas Index, 1979–2008: Background.. PDF (p. 18)

- "Table 2.14" (PDF). IPCC Fourth Assessment Report. p. 212.

- Chandler, David L. "How to count methane emissions". MIT News. Retrieved 20 August 2018. Referenced paper is Trancik, Jessika; Edwards, Morgan (25 April 2014). "Climate impacts of energy technologies depend on emissions timing" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 4: 347. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- Vaara, Miska (2003), Use of ozone depleting substances in laboratories, TemaNord, p. 170, ISBN 978-9289308847, archived from the original on 6 August 2011

- Montreal Protocol

- St. Fleur, Nicholas (10 November 2015). "Atmospheric Greenhouse Gas Levels Hit Record, Report Says". New York Times. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- Ritter, Karl (9 November 2015). "UK: In 1st, global temps average could be 1 degree C higher". AP News. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- "Historical Overview of Climate Change Science – FAQ 1.3 Figure 1" (PDF). p. 116. in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007)

- "Chapter 3, IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios, 2000" (PDF). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2000. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (17 November 2007). "Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report" (PDF). p. 5. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- Blasing (2013)

- Ehhalt, D.; et al., "Table 4.1", Atmospheric Chemistry and Greenhouse Gases, archived from the original on 3 January 2013, in IPCC TAR WG1 (2001), pp. 244–45. Referred to by: Blasing (2013). Based on Blasing (2013): Pre-1750 concentrations of CH4,N2O and current concentrations of O3, are taken from Table 4.1 (a) of the IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2001. Following the convention of IPCC (2001), inferred global-scale trace-gas concentrations from prior to 1750 are assumed to be practically uninfluenced by human activities such as increasingly specialized agriculture, land clearing, and combustion of fossil fuels. Preindustrial concentrations of industrially manufactured compounds are given as zero. The short atmospheric lifetime of ozone (hours-days) together with the spatial variability of its sources precludes a globally or vertically homogeneous distribution, so that a fractional unit such as parts per billion would not apply over a range of altitudes or geographical locations. Therefore a different unit is used to integrate the varying concentrations of ozone in the vertical dimension over a unit area, and the results can then be averaged globally. This unit is called a Dobson Unit (D.U.), after G.M.B. Dobson, one of the first investigators of atmospheric ozone. A Dobson unit is the amount of ozone in a column that, unmixed with the rest of the atmosphere, would be 10 micrometers thick at standard temperature and pressure.

- Because atmospheric concentrations of most gases tend to vary systematically over the course of a year, figures given represent averages over a 12-month period for all gases except ozone (O3), for which a current global value has been estimated (IPCC, 2001, Table 4.1a). CO

2 averages for year 2012 are taken from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Earth System Research Laboratory, web site: www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends maintained by Dr. Pieter Tans. For other chemical species, the values given are averages for 2011. These data are found on the CDIAC AGAGE web site: http://cdiac.ornl.gov/ndps/alegage.html or the AGAGE home page: http://agage.eas.gatech.edu. - Forster, P.; et al., "Table 2.1", Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing, archived from the original on 12 October 2012, retrieved 30 October 2012, in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007), p. 141. Referred to by: Blasing (2013)

- Prentice, I.C.; et al. "Executive summary". The Carbon Cycle and Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009., in IPCC TAR WG1 (2001), p. 185. Referred to by: Blasing (2013)

- Recent CO

2 concentration (395.4 ppm) is the 2013 average taken from globally averaged marine surface data given by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Earth System Research Laboratory, website: http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/index.html#global. Please read the material on that web page and reference Dr. Pieter Tans when citing this average (Dr. Pieter Tans, NOAA/ESRL http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends). The oft-cited Mauna Loa average for 2012 is 393.8 ppm, which is a good approximation although typically about 1 ppm higher than the spatial average given above. Refer to http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends for records back to the late 1950s. - ppb = parts-per-billion

- The first value in a cell represents Mace Head, Ireland, a mid-latitude Northern-Hemisphere site, while the second value represents Cape Grim, Tasmania, a mid-latitude Southern-Hemisphere site. "Current" values given for these gases are annual arithmetic averages based on monthly background concentrations for year 2011. The SF

6 values are from the AGAGE gas chromatography – mass spectrometer (gc-ms) Medusa measuring system. - "Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE)". Data compiled from finer time scales in the Prinn; etc (2000). "ALE/GAGE/AGAGE database".

- The pre-1750 value for N

2O is consistent with ice-core records from 10,000 BCE through 1750 CE: "Summary for policymakers", Figure SPM.1, IPCC, in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007), p. 3. Referred to by: Blasing (2013) - Changes in stratospheric ozone have resulted in a decrease in radiative forcing of 0.05 W/m2: Forster, P.; et al., "Table 2.12", Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing, archived from the original on 28 January 2013, retrieved 30 October 2012, in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007), p. 204. Referred to by: Blasing (2013)

- "SF

6 data from January 2004". "Data from 1995 through 2004". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Halogenated and other Atmospheric Trace Species (HATS). Sturges, W.T.; et al. "Concentrations of SF

6 from 1970 through 1999, obtained from Antarctic firn (consolidated deep snow) air samples". - File:Phanerozoic Carbon Dioxide.png

- Berner, Robert A. (January 1994). "GEOCARB II: a revised model of atmospheric CO

2 over Phanerozoic time" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 294 (1): 56–91. Bibcode:1994AmJS..294...56B. doi:10.2475/ajs.294.1.56. - Royer, D.L.; R.A. Berner; D.J. Beerling (2001). "Phanerozoic atmospheric CO

2 change: evaluating geochemical and paleobiological approaches". Earth-Science Reviews. 54 (4): 349–92. Bibcode:2001ESRv...54..349R. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(00)00042-8. - Berner, Robert A.; Kothavala, Zavareth (2001). "GEOCARB III: a revised model of atmospheric CO

2 over Phanerozoic time" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 301 (2): 182–204. Bibcode:2001AmJS..301..182B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.393.582. doi:10.2475/ajs.301.2.182. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2004. - Beerling, D.J.; Berner, R.A. (2005). "Feedbacks and the co-evolution of plants and atmospheric CO

2". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102 (5): 1302–05. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.1302B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408724102. PMC 547859. PMID 15668402. - Hoffmann, PF; AJ Kaufman; GP Halverson; DP Schrag (1998). "A neoproterozoic snowball earth". Science. 281 (5381): 1342–46. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.1342H. doi:10.1126/science.281.5381.1342. PMID 9721097. S2CID 13046760.

- Siegel, Ethan. "How Much CO2 Does A Single Volcano Emit?". Forbes. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Gerlach, TM (1991). "Present-day CO

2 emissions from volcanoes". Transactions of the American Geophysical Union. 72 (23): 249–55. Bibcode:1991EOSTr..72..249.. doi:10.1029/90EO10192. - See also: "U.S. Geological Survey". 14 June 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- Flückiger, Jacqueline (2002). "High-resolution Holocene N

2O ice core record and its relationship with CH

4 and CO

2". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 16: 1010. Bibcode:2002GBioC..16a..10F. doi:10.1029/2001GB001417. - Friederike Wagner; Bent Aaby; Henk Visscher (2002). "Rapid atmospheric CO

2 changes associated with the 8,200-years-B.P. cooling event". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99 (19): 12011–14. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9912011W. doi:10.1073/pnas.182420699. PMC 129389. PMID 12202744. - Andreas Indermühle; Bernhard Stauffer; Thomas F. Stocker (1999). "Early Holocene Atmospheric CO

2 Concentrations". Science. 286 (5446): 1815. doi:10.1126/science.286.5446.1815a. IndermÜhle, A (1999). "Early Holocene atmospheric CO

2 concentrations". Science. 286 (5446): 1815a–15. doi:10.1126/science.286.5446.1815a. - H. J. Smith; M. Wahlen; D. Mastroianni (1997). "The CO

2 concentration of air trapped in GISP2 ice from the Last Glacial Maximum-Holocene transition". Geophysical Research Letters. 24 (1): 1–4. Bibcode:1997GeoRL..24....1S. doi:10.1029/96GL03700. - Charles J. Kibert (2016). "Background". Sustainable Construction: Green Building Design and Delivery. Wiley. ISBN 978-1119055327.

- "Full Mauna Loa CO2 record". Earth System Research Laboratory. 2005. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Tans, Pieter (3 May 2008). "Annual CO

2 mole fraction increase (ppm) for 1959–2007". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Earth System Research Laboratory, Global Monitoring Division. "additional details".; see also Masarie, K.A.; Tans, P.P. (1995). "Extension and integration of atmospheric carbon dioxide data into a globally consistent measurement record". J. Geophys. Res. 100 (D6): 11593–610. Bibcode:1995JGR...10011593M. doi:10.1029/95JD00859. - "Global Carbon Project (GCP)". www.globalcarbonproject.org. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- Dumitru-Romulus Târziu; Victor-Dan Păcurar (January 2011). "Pădurea, climatul și energia". Rev. pădur. (in Romanian). 126 (1): 34–39. ISSN 1583-7890. 16720. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2012.(webpage has a translation button)

- Held, Isaac M.; Soden, Brian J. (November 2000). "Water vapor feedback and global warming". Annual Review of Energy and the Environment. 25 (1): 441–475. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.22.9397. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.25.1.441. ISSN 1056-3466.

- Evans, Kimberly Masters (2005). "The greenhouse effect and climate change". The environment: a revolution in attitudes. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 978-0787690823.

- "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2010". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 15 April 2012. p. 1.4. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Climate Change Indicators in the United States". NOAA. 2012. Figure 4. The Annual Greenhouse Gas Index, 1979–2011.

- "Climate Change Indicators in the United States". US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2010. Figure 2. Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector, 1990–2005.

- "Climate Change 2001: Working Group I: The Scientific Basis: figure 6-6". Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- "The present carbon cycle – Climate Change". Grida.no. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- Couplings Between Changes in the Climate System and Biogeochemistry (PDF). Retrieved 13 May 2008. in IPCC AR4 WG1 (2007)

- IPCC (2007d). "6.1 Observed changes in climate and their effects, and their causes". 6 Robust findings, key uncertainties. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Geneva: IPCC. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "6.2 Drivers and projections of future climate changes and their impacts". 6 Robust findings, key uncertainties. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC. 2007d. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "3.3.1 Impacts on systems and sectors". 3 Climate change and its impacts in the near and long term under different scenarios. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Geneva: IPCC. 2007d. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. (2006). Livestock's long shadow (Report). FAO Livestock, Environment and Development (LEAD) Initiative.

- Ciais, Phillipe; Sabine, Christopher; et al. "Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles" (PDF). In Stocker Thomas F.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. IPCC. p. 473.

- Michael Clark; Tilman, David (November 2014). "Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health". Nature. 515 (7528): 518–522. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..518T. doi:10.1038/nature13959. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25383533.

- Raupach, M.R.; et al. (2007). "Global and regional drivers of accelerating CO

2 emissions" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104 (24): 10288–93. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410288R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700609104. PMC 1876160. PMID 17519334. - Grubb, M. (July–September 2003). "The economics of the Kyoto protocol" (PDF). World Economics. 4 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

- Lerner & K. Lee Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth (2006). "Environmental issues: essential primary sources". Thomson Gale. Retrieved 11 September 2006.

- "Kyoto Protocol". United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Home > Kyoto Protocol.

- King, D.; et al. (July 2011), "Copenhagen and Cancún", International climate change negotiations: Key lessons and next steps, Oxford: Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, p. 12, doi:10.4210/ssee.pbs.2011.0003 (inactive 8 June 2020), archived from the original on 1 August 2013 "PDF available" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2012.

- Johnston, Chris; Milman, Oliver; Vidal, John (15 October 2016). "Climate change: global deal reached to limit use of hydrofluorocarbons". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Climate change: 'Monumental' deal to cut HFCs, fastest growing greenhouse gases". BBC News. 15 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- "Nations, Fighting Powerful Refrigerant That Warms Planet, Reach Landmark Deal". New York Times. 15 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- "Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector". EarthCharts. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Climate Watch". www.climatewatchdata.org. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- IEA, CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2018: Highlights (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2018) p.98

- IEA, CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2018: Highlights (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2018) p.101

- "March: Tracking the decoupling of electricity demand and associated CO2 emissions". www.iea.org. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Emissions". www.iea.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "We have too many fossil-fuel power plants to meet climate goals". Environment. 1 July 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Environmental Impacts of Tourism – Global Level". UNEP.

- "A Cheaper and More Efficient Freight Industry In and Out of the UK". freightbestpractice.org.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Newbold, Richard (19 May 2014), A practical guide for fleet operators, returnloads.net, retrieved 20 January 2017.

- Glazner, Elizabeth. "Plastic Pollution and Climate Change". Plastic Pollution Coalition. Plastic Pollution Coalition. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Blue, Marie-Luise. "What Is the Carbon Footprint of a Plastic Bottle?". Sciencing. Leaf Group Ltd. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Royer, Sarah-Jeanne; Ferrón, Sara; Wilson, Samuel T.; Karl, David M. (1 August 2018). "Production of methane and ethylene from plastic in the environment". PLOS ONE. 13 (Plastic, Climate Change): e0200574. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1300574R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200574. PMC 6070199. PMID 30067755.

- Rosane, Olivia (2 August 2018). "Study Finds New Reason to Ban Plastic: It Emits Methane in the Sun" (Plastic, Climate Change). Ecowatch. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- EPA (2012). "Landfilling" (PDF).

- Levis, James W.; Barlaz, Morton A. (July 2011). "Is Biodegradability a Desirable Attribute for Discarded Solid Waste? Perspectives from a National Landfill Greenhouse Gas Inventory Model". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (13): 5470–5476. Bibcode:2011EnST...45.5470L. doi:10.1021/es200721s. PMID 21615182.

- "Sweeping New Report on Global Environmental Impact of Plastics Reveals Severe Damage to Climate". Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Plastic & Climate The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet (PDF). Center for International Environmental Law, Environmental Integrity Project, FracTracker Alliance, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, 5 Gyres, and Break Free From Plastic. May 2019. pp. 82–85. Retrieved 20 May 2019.