1,1,2-Trichloro-1,2,2-trifluoroethane

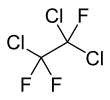

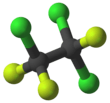

1,1,2-Trichloro-1,2,2-trifluoroethane, also called trichlorotrifluoroethane or CFC-113, is a chlorofluorocarbon. It has the formula Cl2FC-CClF2. This colorless, volatile liquid is a versatile solvent.[4]

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,1,2-Trichloro-1,2,2-trifluoroethane | |||

| Other names

CFC-113 Freon 113 Frigen 113 TR Freon TF | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.852 | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C2Cl3F3 | |||

| Molar mass | 187.37 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | like carbon tetrachloride[1] | ||

| Density | 1.56 g/mL | ||

| Melting point | −35 °C (−31 °F; 238 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 47.7 °C (117.9 °F; 320.8 K) | ||

| 170 mg/L | |||

| Vapor pressure | 285 mmHg (20 °C)[1] | ||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.0729 W m−1 K−1 (300 K)[2] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LCLo (lowest published) |

250,000 ppm (mouse, 1.5 hr) 87,000 (rat, 6 hr)[3] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 1000 ppm (7600 mg/m3)[1] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1000 ppm (7600 mg/m3) ST 1250 ppm (9500 mg/m3)[1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

2000 ppm[1] | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Atmospheric reactions

CFC-113 is a very unreactive chlorofluorocarbon. It remains in the atmosphere about 90 years,[5] sufficiently long that it will cycle out of the troposphere and into the stratosphere. In the stratosphere, CFC-113 can be broken up by ultraviolet radiation (where sunlight in the 190-225 nm (UV) range), generating chlorine radicals (Cl•), which initiate degradation of ozone requiring only a few minutes:[6][7]

- C2F3Cl3 → C2F3Cl2 + Cl•

- Cl• + O3 → ClO• + O2

This reaction is followed by:

- ClO• + O → Cl• + O2

The process regenerates Cl• to destroy more O3. The Cl• will destroy an average of 100,000 O3 molecules during its atmospheric lifetime of 1–2 years. In some parts of the world, these reactions have significantly thinned the Earth's natural stratospheric ozone layer that shields the biosphere against solar UV radiation; increased UV levels at the surface can cause skin cancer or even blindness.[8]

Uses

CFC-113 was one of the most heavily produced CFCs. In 1989, an estimated 250,000 tons were produced.[4] It has been used as a cleaning agent for electrical and electronic components.[8] CFC-113 is one of the three most popular CFCs, along with CFC-11 and CFC-12.[9]

CFC-113’s low flammability and low toxicity made it ideal for use as a cleaner for delicate electrical equipment, fabrics, and metals. It would not harm the product it was cleaning, ignite with a spark or react with other chemicals.[10]

CFC-113 in laboratory analytics has been replaced by other solvents.[11]

Reduction of CFC-113 with zinc gives chlorotrifluoroethylene:[4]

- CFCl2-CClF2 + Zn → CClF=CF2 + ZnCl2

References

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0632". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Touloukian, Y.S., Liley, P.E., and Saxena, S.C. Thermophysical properties of matter - the TPRC data series. Volume 3. Thermal conductivity - nonmetallic liquids and gases. Data book. 1970.

- "1,1,2-Trichloro-1,2,2-trifluoroethane". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Siegemund, Günter; Schwertfeger, Werner; Feiring, Andrew; Smart, Bruce; Behr, Fred; Vogel, Herward; McKusick, Blaine (2002). "Fluorine Compounds, Organic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_349.

- "Global Change 2: Climate Change". University of Michigan. January 4, 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-04-20. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- Molina, Mario J. (1996). "Role of chlorine in the stratospheric chemistry". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 68 (9): 1749–1756. doi:10.1351/pac199668091749.

- "Guides | SEDAC".

- "Chlorofluorocarbons". Columbia Encyclopedia. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- Zumdahl, Steven (1995). Chemical Principles. Lexington: D. C. Heath. ISBN 978-0-669-39321-7.

- "Guides | SEDAC". sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu.

- "Use of Ozone Depleting Substances in Laboratories. TemaNord 516/2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-05-06.