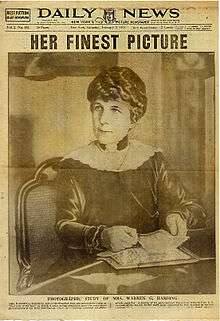

Florence Harding

Florence Mabel Harding (née Kling; August 15, 1860 – November 21, 1924) was the First Lady of the United States from 1921 to 1923 as the wife of President Warren G. Harding.

Florence Harding | |

|---|---|

| |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923 | |

| President | Warren G. Harding |

| Preceded by | Edith Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Grace Coolidge |

| Second Lady of Ohio | |

| In role January 11, 1904 – January 8, 1906 | |

| Lieutenant Governor | Warren G. Harding |

| Preceded by | Esther Gordon |

| Succeeded by | Caroline Harris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Florence Mabel Kling August 15, 1860 Marion, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 21, 1924 (aged 64) Marion, Ohio, U.S. |

| Resting place | Harding Tomb |

| Spouse(s) | Henry DeWolfe

( m. 1880; div. 1886) |

| Children | Marshall |

| Education | Cincinnati Conservatory of Music |

| Signature | |

| [1] | |

| External video | |

|---|---|

Florence married Pete De Wolfe at a young age and had a son, Marshall. After divorcing him, she married the somewhat-younger Harding when he was a newspaper publisher in Ohio, and she was acknowledged as the brains behind the business. Known as The Duchess, she adapted well to the White House, where she gave notably elegant parties.

Early life

She was born Florence Mabel Kling above her father's hardware store at 127 South Main Street in Marion, Ohio on August 15, 1860. Florence was the eldest of three children of Amos Kling, a prominent Marion accountant and businessman of German descent, and Louisa Bouton Kling, whose French Huguenot ancestors had fled religious persecution. Her younger brothers were Clifford, born in 1861, and Vetallis, born in 1866. Florence attended school at Union School beginning in 1866 and studied the classics. Her father prospered as a banker and was a stockholder in the Columbus & Toledo Railroad, President of the Agricultural Society, and member of the school board.[2] Florence developed a passion for horses early in life and participated in several horse races. Her father trained her in several business skills such as banking, real estate, and farm management.[3]

Aiming to become a concert pianist, Florence began studies at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music after graduating from high school in 1876. As she recalled, she spent seven hours per day on the piano for three years, once playing until her finger bled. On return trips to Marion, Florence often clashed with her father, who would whip her with a cherry switch.[4] At the age of 19 she eloped with Henry Atherton ("Pete") De Wolfe (4 May 1859, Marion – 8 March 1894, Marion) and they were married in Columbus, Ohio, on January 22, 1880.[5] A record of the issuance of their marriage license was printed in The Marion Star.[6] Florence gave birth to her only child, Marshall Eugene, on September 22, 1880. Her husband worked in a warehouse but became a heavy drinker and abandoned the family on December 31, 1882. Florence moved in with her friend Carrie Wallace while her mother Louisa financially supported the mother and child.[7] Florence became a piano teacher to provide extra income and enjoyed skating at night. Her estranged husband had attempted to rob a train in 1885, and the pair were divorced in 1886.[8]

Eventually, Amos Kling offered to adopt Marshall but would not provide for his daughter. As a result, Marshall adopted the Kling surname despite not being legally adopted. This freed Florence for other romantic flings, and she soon met Warren Gamaliel Harding, owner of the Marion Star. He was five years younger than she was, and his sister Charity was a student of Florence's. Soon the Marion Star reported on Florence's trips to Yellowstone National Park with her mother and Warren Harding. Harding and Florence became a couple by the summer of 1886.[9] Who was pursuing whom is uncertain, depending on who later told the story of their romance.[10]

Marriage to Harding

In 1890, Florence became engaged to Warren Harding. They married on July 8, 1891, opposed by her father, who thought Warren was social climbing and had a wealthier suitor in mind for his daughter. He repeated a rumor that Harding had black ancestry and threatened to shoot the young man at the courthouse.[11] After the wedding, which Florence's mother secretly attended, the couple embarked on a honeymoon tour of Chicago, St. Paul, Yellowstone, and the Great Lakes. The new Mrs. Harding made the unconventional decision not to wear a wedding ring.[12] Warren referred to her as "the boss", while she affectionately called him "Sonny."[13]

They had no children of their own, but Florence's son Marshall lived with them intermittently and received encouragement from Warren to work in journalism.[14] When her husband entered the Battle Creek Sanitarium for depression in January 1894, Florence became the informal business manager of the Marion Star though never had any official role, immediately demonstrating both the talent and the character to run a newspaper.[15] She organised a circulation department, improved distribution, trained the newsboys, and purchased equipment at keen prices. Her newsboys became known as "Mrs. Harding's boys" throughout the town, and she alternatively gave out awards for achievement and doled out physical punishment. Some Marion children began to fear Florence for paddling the boys in the street. One of the newsboys, Norman Thomas, later the Socialist presidential candidate, declared that Warren was the front-man, but Florence was the real driving power of the Marion Star.[16]

Warren returned to work on the Star in December 1894 though Florence continued to nurse him at home. After the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Florence was instrumental in developing the first wire report. Although she never wrote any articles, she did suggest stories based on leads she had, particularly stories to appeal to women. She hired the first woman reporter in Ohio, Jane Dixon, and supported her when there was a backlash from the people of Marion. Through Florence's leadership, the Star prospered and increased its revenue. She also knew about the machinery of the newspaper plant and how to fix it. Though Warren was not particularly supportive of women's rights at the time, belittling rallies for temperance, he greatly appreciated his wife's help at the office and respected her frank opinions.[17] Florence wrote of her husband, "he does well when he listens to me and poorly when he does not."[18]

Florence encouraged her husband in his first political run for state senate in 1899. She managed the finances and fended off unsurprising objections from her father, who enlisted Mark Hanna for help, though Warren was ultimately elected.[19] Florence observed the legislature from the balcony and frequently made trips to newspaper offices to win her husband good coverage and observe their operations. She also began her custom of consulting with an astrologer during this first stint in Columbus. Encouraging her husband to be pragmatic and not to alienate anyone, he was reelected in 1901. In 1903, he was elected lieutenant governor. Journalist Mark Sullivan wrote of Florence, "As a wife, she had that particular kind of eagerness to make good which, in a personality that is at once superficial and unsure of itself, sometimes manifests itself in a too strenuous activity, a too steady staying on the job."[20]

In February 1905, Florence needed emergency surgery for nephroptosis ('floating kidney'), and was initially treated by homeopathic doctor Charles E. Sawyer. His close links with the Harding family, and Florence's total trust and dependence on him, would later prove controversial. Sawyer referred Florence to Dr. Jamez Fairchild Baldwin, who "wired" the kidney in place and did not remove it due to heart damage that she had already suffered. Confined to a hospital bed for weeks, Florence later stated this experience made her more empathetic for hospital patients.[21] During her convalescence, Warren began an affair with a close friend of hers, Carrie Phillips, who had recently lost a child.[22] Florence did not find out until she intercepted a letter between the two in 1911, which led her to consider divorce, though she never pursued it. Apparently she considered herself too invested in her husband's career to leave him, though her discovery of the affair did not end it. It was one of several adulterous escapades that Warren embarked upon, of which Florence found herself increasing resigned though she expressed her disapproval. She tried to discourage the affairs by sticking by her husband's side at all times.[23] Florence never spoke to Carrie Phillips again, and only acknowledged her in bitter attacks.[24]

Warren and Florence left for a trip to Europe in August 1911. During her stay in England, Florence began to sympathize with women leading protests and became an ardent suffragette. When she returned to America, she went to a rally for women's right to vote in Columbus. Despite her feelings on the matter, Florence remained silent on women's suffrage during the 1912 election.[25] She continued to be treated by Dr. Sawyer at his new White Oaks Sanitarium for various ailments and deepened her study of astrology. Florence also gave her husband advice on his political chances, discouraging a run for governor in 1912. Instead, she had her sights set on Washington, D.C., and Warren broadened his national reputation by very publicly supporting William Howard Taft at the Republican convention. After Taft was defeated by Woodrow Wilson in the election, Warren sought refuge by writing poetry to Carrie Phillips.[26]

On October 20, 1913, Florence's father passed away. Despite their strained relationship, his daughter received $35,000 and valuable real estate in the will. Florence had her own health problems, suffering a serious kidney attack in the winter of 1913 and went to live at the White Oaks Sanitarium. Dr. Sawyer feared that Florence would not survive the year, but his patient managed to recover. In spite of her ill health, she encouraged her husband to run for Senate in 1914, and resolved to be part of the campaign.[27] She limited her role to advisory management and persuaded her husband to ignore pressures to have anti-Catholic remarks against the Democratic opponent, Timothy Hogan. With her assistance, Warren won the Senate election by 102,000 votes.[28]

Florence's son Marshall died on January 1, 1915, of tuberculosis. She made a trip to Colorado later in the year to pay his debts and ended up becoming friendly with some of his associates and wife Esther. Along with her husband, she travelled to California and Hawaii before settling into life in Washington, D.C. as the wife of a senator. After returning from Marion, Florence decided to rent a house in the Kalorama neighborhood of D.C.[29] In January 1916, Florence suffered from heart palpitations, and she called Dr. Sawyer to help with her mental health. To cope with a growing depression, she helped furnish the new house and hired staff for assistance.[30] Florence helped her husband with his correspondence and invited press attention. Despite her stand on suffrage, she could not persuade Warren in 1916 to make up his mind, as he preferred partisan leadership.[31]

Florence became active in animal rights and joined the Animal Rescue League, Humane Society, and ASPCA. She spoke out against animal cruelty and gave freely of its literature to friends. In a brief autobiography in 1916, she mentioned her fondness for horses and concern about their abuse. Florence did not like automobiles, but relented when making frequent trips back to Marion.[32] In Washington D.C., Florence struck up a fast friendship with the mining heiress Evalyn Walsh McLean, frequently playing bridge and visiting movie theaters. As a result, Warren wrote to Dr. Sawyer in April 1917, "Mrs. Harding is well and looking better than she has for three or four years.[33]

After the U.S. entered World War I, Florence occupied herself in working toward a victory. She helped Ohio women who moved to Washington, D.C. for jobs find housing, and helped Lou Hoover set up dining and recreation spaces for the female workers. Florence frequently visited nurseries and daycare centers to assist mothers who had to work during the day. Alongside other political spouses, she handed out tin cups of coffee and sandwiches to soldiers departing from Union Station. Florence also volunteered at the Walter Reed Hospital, and found a sense of satisfaction in this work missing from her heretofore existence. She worked with other Senate wives to create a Red Cross Unit and produce clothing for soldiers on the battlefield. In order to better monitor the events on the front, Florence avidly read several newspapers and learned the pronunciation of foreign towns and locations.[34]

Warren's continued his affair with Carrie Phillips, alongside other women like the young Nan Britton, despite the suspicion that Phillips was a German spy. This proved to be untrue, though she did have sympathies with the German cause. Florence found out about this fact, perhaps being told by her husband, and reacted with rage. During the summer of 1918, while greeting soldiers leaving from the Marion train station, Florence spotted Phillips complaining about the futility of sending men to fight. Florence approached her and got into a heated argument, publicly rebuking her in front of many onlookers. Despite this public display of his wife's temper, Warren soon after sent Carrie love letters proclaiming his devotion, albeit with the caveat that a divorce from Florence was not feasible.[35]

In November 1918, Florence's kidney swelled to ten times its regular size. This was perhaps her worst attack since 1905 and left her bedridden for weeks. She was treated by Dr. Sawyer's son Carl, who had been stationed at Camp Meade (now Fort Meade). Warren stayed at her side until it was clear she was feeling better.[36] By March 1919 Florence had recovered enough to attend events at Evalyn's house while her husband golfed.[37] Florence was in attendance at the Senate on July 10 when President Wilson requested America join the League of Nations, an idea she opposed. During the summer, her husband began to be mentioned as a potential presidential candidate, which Florence was initially not happy with since she thought he didn't have enough of a national reputation.[38]

By 1920, he was a contender for the Republican presidential nomination, though not a front-runner. Florence gave him tentative support, apparently influenced by a Washington clairvoyant 'Madame Marcia' Champrey, who correctly forecast that Warren would become President, but added that he would die in office.[39] Florence took a more active role at the Republican convention than most candidates wives and curried favor with journalists, who liked to record her often colorful remarks.[40] She lobbied delegates to consider her husband after the convention became deadlocked, and he eventually became the nominee.[41] Warren largely conducted a front porch campaign, and Florence had control of whom her husband met inside the house. She was very precise with her appointments for her husband and telephoned campaign managers if he was late.[42] She set off a waffle craze after The New York Times reported her eating a waffle at breakfast, and guests asked to be served it during their visit.[43] The election was overshadowed by attempted extortion by Carrie Phillips, threatening to reveal Warren's adultery. However, Florence's newspaper experience gave her an advantage over other candidates' wives; as Henry DeWolfe was dead, she was able to deflect press inquiries about her first marriage by implying that she had been widowed. In addition, she instructed the campaign not to respond to allegations of Warren's partial black ancestry.[39] Florence also earned the approval of ex-President Taft.[44]

On election night, Warren received 404 electoral votes, defeating Democratic challenger James M. Cox who received 127. In the celebration, a mob of supporters lifted Florence on their shoulders. She seemed not particularly enthusiastic about the prospect of becoming the First Lady, telling a friend "I don't feel any too confident, I can tell you. I haven't any doubt about him, but I'm not so sure of myself."[45] Following the election, departing First Lady Edith Wilson invited Florence to the White House for a tour of her future home. Florence accepted, provided her friend Evalyn, who was previously very critical of the Wilsons, was invited as well. After a disagreement over tea, Edith had her housekeeper give the tour.[46]

As First Lady

On March 4, 1921, Florence Harding became First Lady, immediately taking an active role in national politics, at times even appearing to dominate the President.[47] She had a strong influence on the selection of cabinet members, in particular favoring Charles R. Forbes as director of the Veterans Bureau and Andrew Mellon as treasury secretary. She approved of the selection of Charles Evans Hughes as secretary of state though privately thought Elihu Root would be a better pick.[48] At the inauguration, observers believed that she was prompting her husband with a speech she had written, as there were several references to women's new role in American political life. Florence ensured that everyone who worked for the campaign in Marion was invited to the inauguration, and asked a woman that fainted in the crowds be helped.[49] Secret service agent Harry L. Barker was assigned to protect Florence, making her the first First Lady to have her own agent. The two developed a close, trusting partnership with each other.[50]

After Warren addressed the Senate, Florence asked her husband, "Well, Warren Harding, I have got you the Presidency. What are you going to do with it?" He replied, "May God help me, for I need it."[51] In Warren's first pronouncement as president, he ordered that the gates of the White House be opened to the public as per Florence's wishes. The move was praised by the press, with an announcement that tourists could come to the property in the following week. Florence told a senator that she was aiming to become the most successful First Lady in history. By the time the White House opened to the public, Florence offered to act as tour guide herself. Many different groups and individuals came to meet the First Lady, ranging from Bill Tilden to Albert Einstein.[52]

Florence read mail after breakfast and wrote invitations for social events. She was the first First Lady to send original responses to the many letters received. She would often stand at the south portico to get her photograph taken with large groups. The New York Tribune praised her as being "far more generous receiving special groups at the White House than were her predecessors."[53] She obsessed over her appearance but insisted she hated clothes. By wearing long skirts, she was somewhat out of style with the new fad being flapper dresses, but Florence remarked that she had no right to dictate how short the skirts should be. In addition, she launched new fashions like the silk black neckband, which became known as "Flossie Clings" after her maiden name. She carried small bouquets of blue-violet flowers to complement her blue eyes. Despite her emphasis on fashion, Florence was economical elsewhere in the White House budget, which was highly praised in the wake of the 1921 recession.[54]

As a White House hostess, Florence presided over elegant parties that often had several thousand guests where her husband would refer to her as The Duchess. These parties were largely a continuation of the front porch campaign, and she also had dinner parties on the presidential yacht. Florence relished in her role as White House tour guide, learning about the history of the property from books and displaying a portrait of Sarah Yorke Jackson. Despite her growing popularity with the public, high society largely shunned Florence and favored Second Lady Grace Coolidge, with whom Florence had an uneasy relationship. The couple's dog Laddie Boy was a hit though, sparking a craze for Airedale terriers.[55]

Florence became the first First Lady since Frances Cleveland whose face was so recognizable to the public, as she frequently appeared in newsreel footage alongside Warren unveiling statues, attending baseball games, and dedicating the Lincoln Memorial. Several flowers were named in her honor, and the composer David S. Ireland wrote a song called "Flo from Ohio." Due to the popular interest in psychoanalysis, some psychological profiles were written of her in newspapers. The First Couple increased their popularity by attending movie screenings and meeting actors, who were previously seen as vulgar by high society. Al Jolson was a frequent guest, and Florence gave D.W. Griffith a tour and lunch at the White House. Florence became the first First Lady to appear in movies with her signature wave to crowds. Evalyn McLean taught her how to operate a camera and she made some films of women at the Potomac Park Civic Club. [56]

She became known for her opposition to smoking after a photographer captured her holding down Helen Pratt's arm, who was smoking a cigarette. The Women's Christian Temperance Union urged her to use her influence to advance the antismoking cause, though she politely declined. On the subject of drinking, Florence was an outward proponent of maintaining Prohibition as respect for the law. In private however, she secretly served alcohol to guests. The frequent guests and parties took its toll on Florence, who wrote, "My days are so full I don't know which way to turn," but added "it's a great life if you don't weaken.[57]

Florence worked to protect the image of herself and Warren, concealing his drinking, womanizing, and corruption in the cabinet. She insisted on being beside him and once told him to get back to work when he was golfing. She was concerned as to her husband's personal safety, partially because of Madame Marcia's prediction of his early demise. Despite the fact there were no public revelations of her meeting with the psychic since the 1920 campaign, the consultations continued in earnest, and Marcia was even invited to the White House. Florence relied on astrology to determine Warren's personal schedule, a fact that became known to many in his inner circle. She also feared his susceptibility to blackmail since the Carrie Phillips debacle.[58] After returning from Japan in 1921, Phillips visited Warren at the White House, much to the chagrin of Florence. Several other women also received money from the President, and Florence employed Gaston Means to spy on Nan Britton to steal her love letters.[59]

A trip to Alaska which Florence eagerly anticipated was planned for the summer of 1921, but had to be postponed in lieu of the work obligations. Instead, the Hardings took a cruise through New England and periodical motor trips. Florence developed a thrill for fast driving, nearly having an accident at fifty miles an hour when her car veered toward a telephone pole. The Budget Bureau director criticized her for this, which she simply shrugged off. She was an avid theatergoer, particularly comedies and musicals. Warren, on the other hand, preferred to watch strippers.[60]

Florence made her views known on everything from the League of Nations to animal rights, racism, and women's rights. She had strong concern for immigrant children trapped by bureaucracy, though criticized "hyphenated Americans." She was willing to risk criticism when she championed social issues, and she never lent her name to a cause unless it moved her. Some of her suggestions were rather radical, including the attempt to cure drug addicts through a vegetarian diet. Florence supported the victims of the Armenian Genocide and personally funded a child survivor with monthly checks. She was willing to forgo a meal and donate to the Chinese Famine fund, but was critical of American support to aid relief of the 1921 Soviet famine, arguing that Russia should have given up communism before accepting American food and medicine. Likewise, she did not support relief for Irish families as it could be seen as anti-British. Florence opposed vivisection in a public letter and supported the Humane Education Society, though she continued to eat meat.[61] Florence's own special agenda was the welfare of war veterans, whose cause she championed wholeheartedly. She referred to them as "our boys".[62] Since World War I had left many men disfigured and ill, Florence went out of her way to care for the patients at Walter Reed Hospital, seeking to improve ward life. Her efforts led to women's groups funding projects at veterans wards which the federal government failed to do.[63]

She lifted the informal ban on "unacceptable women" (usually meaning divorced women) instituted under Theodore Roosevelt. She sparked a small furor by inviting the National Council of Catholic Women to the White House, as liberals disdained their anti-birth control efforts. Florence would not criticize Margaret Sanger's birth control push as she herself had used it earlier in life. Florence hosted a tennis match between Marion Jessup and Molla Mallory. Additionally, she sought to associate with popular female icons of the 1920s. When Madame Curie visited the White House, Florence praised her as an example of a professional achiever and excellent scientist who was also a supportive wife. Florence accepted an inscribed book from the Curies, breaking her informal rule against autographs.[64]

Florence raised public awareness of women who managed household finance. She stated that married women should know something of their husband's work. She agreed to sign on to a pledge to reduce consumption of sugar when its price became exorbitant. However, she also held some traditional values, such as it being more practical for women to raise families rather than working a regular job. Florence became the president of the Southern Industrial Association, an informal role in an organization that provided education for mountain women. She personally helped a man get a job at a factory after his wife wrote asking for help.[65]

She sought to make herself available to the press, a stark contrast with her predecessor Edith Wilson who denied press access. Florence had more press interviews than all the First Ladies before her combined. She enjoyed talking to journalists she liked, such as Kate Forbes and Jane Dixon. Her press conferences, which started a month after inauguration, became a regular event, held over four o'clock tea. Although she frequently discussed politics, she did not like being quoted verbatim in the reports. She referred to female reporters as "us girls", owing to her history in running the Marion Star. Although Florence did not believe herself to be a gifted public speaker, she regularly gave impromptu speeches or "little patriotic addresses" to organizations such as the Red Cross and League of Women Voters.[66]

In public, Florence always bragged about the President and his accomplishments. But in private, she let her political difference be known. She would frequently express how the Executive should best perform his job and tried to prevent or minimize any mistakes. Florence kept up on the latest political news and knew the details of government better than almost any woman of her era. She sometimes argued with him over the content of his speeches, occasionally shaking a finger at him if she was upset. Once she became upset at a speech that proposed a single presidential term of six years and refused to leave until the clause was omitted. If the discussion ever became too heated, Warren would leave the room to express his irritation, but he never scolded her.[67]

Florence even had a hand in selecting minor public officials, particularly postmasters. In terms of patronage, she would place party loyalty above personal connections though she did pick several Democrats for postmaster. Former coworkers at the Marion Star only received her consideration if they had a documented partisan streak. Her authority was respected by politicians from all levels of governance. When she wanted information on someone, Florence used unconventional methods particularly on Herbert Hoover, whom she disliked. She informed Senator Hiram Johnson that his Democratic challenger was a stooge for Hoover, which caused Johnson to send election information to her via Evalyn McLean. In response to the 1921 recession, the government reviewed government agencies in hopes of consolidation, and Florence herself checked budgets and requested a memo from the Marines about the cost of uniforms.[68]

Attorney general Harry M. Daugherty was the Cabinet member with which Florence was the most political. Florence scheduled private citizens to meet with him, and in return he always complied with her requests. One time she asked Daugherty to look into the case of the Bosko brothers in West Virginia who were convicted of burglary. On closer inspection, the case relied on flimsy evidence including forced confessions and all three were issued presidential pardons. Florence requested that Daugherty commute a death sentence in Alabama, but he replied that the Justice Department had no jurisdiction in the case. Other Cabinet members obeyed her, with Albert Fall assuring her that the Interior Department would pay immediate attention to any request that she forwarded. Her authority received some ribbing from Life magazine, which depicted "The Chief Executive and Mr. Harding" in a 1922 cartoon.[69]

Both Warren and Florence Harding were relatively progressive on the subject of race, although the President largely toned down his rhetoric when giving speeches in the South. An important exception to this was a speech in Alabama in which he favored equality between the races, while Florence loudly applauded a black band in a parade. Florence fought racism in under-the-radar ways. She pressured her husband to rescind an appointment of Helen Dortch Longstreet to a political position since she favored rule by white men only. In terms of international affairs, Florence was not as active, although she did participate in the International Conference on the Limitation of Armaments from November 1921 to February 1922. She considered her role important in bringing together the various nations in a common understanding. She took part in the burial of "Buddy" in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, reflecting her longstanding interest in veterans' affairs.[70]

Florence insisted her family spend Christmas 1921 with the McLeans after hearing about a bomb threat against Warren. Bombs intended for the President were found the next day, making Florence appear wise in retrospect. By the end of Harding's first year in office, newspapers wrote assessments of his performance, largely praising Florence's role in the administration. However, negativity against her appeared after a House Appropriations Committee hearing found that the $50,000 budget for the White House had been almost completely spent, largely due to her entertaining so many people and reopening the grounds to tourists. The head groundskeeper estimated that it would cost $3000 to repair the greenhouses due to how many flowers Florence displayed in the White House. Throughout the winter, Florence was eager to join Evalyn in Florida, but when they arrived Warren continued his womanizing publicly, to the chagrin of his wife.[71]

After returning from Florida, the Hardings met the oil tycoon Edward L. Doheny. an associated of Interior Secretary Albert Fall. Warren's approval of oil leases to Doheny would result in the Teapot Dome Scandal, and while Harding did not profit from it, Fall did, handsomely. In May 1922, Florence met and became close to a naval doctor, Joel Thompson Boone, who relished his presidential posting. Boone also became acquainted with Dr. Sawyer, who was becoming increasingly unpopular in the veterans bureau. In July, the Hardings returned to Marion to take part in its centennial celebration. Florence greeted Nan Britton during the festivities, unaware she was carrying on an affair with her husband.[72]

In August, the President addressed Congress regarding the increasingly economically damaging coal and rail strikes. Florence followed the events of the strikes closely, while Warren drank excessively to deal with the anxiety it brought about in him. Florence instructed her Secret Service agent Harry Barker to keep tabs on her husband, especially if she happened to be away from him. Her discovery of the affair with Nan Britton took its toll on her health. In early September she came down with a serious kidney ailment, and the public was alerted as to the severity of it on September 8 in a medical bulletin. The eminent physician Charles Horace Mayo was called in to treat her, which sparked jealousy from Dr. Sawyer. By the time he arrived, the First Lady was suffering from septicemia and was falling in and out of consciousness.[73]

News of Florence's illness sparked an outpouring of support throughout the country. It sparked many editorials in newspapers and a rumor that she had passed, which was dispelled. The gates of the White House were opened to accommodate the thousands of well-wishers who came to pray for the First Lady. Dr. Mayo insisted that emergency surgery was the only option to save Florence, but Dr. Sawyer disagreed. He eventually gave the option to Florence, who was now lucid and did not favor surgery. By September 11 her condition had worsened that, as she later related, she had a near death experience seeing two figures at the end of her bed. Florence insisted she would not die because her husband needed her. As she fought back from what she called the "Valley of Death", Florence spontaneously relieved an obstruction and required bed care from the nurses. Her condition gradually improved to the point that Dr. Mayo did not feel his service was necessary.[74]

A sign of Florence's improving condition was the re-opening of the White House to tourists on October 1. She was informed of Republican losses the day after the midterm elections and was incredulous that several Senators had lost. In her improving condition, Florence continued to campaign for war veterans, starting a "Forget-Me-Not" drive by purchasing the first flower from her room. She continued to keep tabs on who was entering and exiting the White House, which prompted Warren to use the Friendship estate for his rendezvous with Nan Britton. By Thanksgiving, Florence was well enough to preside over her first dinner since the illness. On December 7 she insisted she meet with Georges Clemenceau, who was having lunch with Warren.[75]

Florence had a session with psychologist Émile Coué to deal with the frustration during her convalescence after being impressed with his writings. Her illness and recovery took its toll on her husband, who did show genuine care for her but also wanted more freedom for himself. Florence declared, "this illness has been a blessing," since it drew the two closer together. Warren read to her in bed about Yellowstone Park, a place which she longed to return. Florence also placed her complete trust in Dr. Sawyer, whom Warren believed had brought her back to life. In January 1923, Warren took ill and was bedridden for weeks. Florence was responsible for making sure he did not undertake much work during his illness, once sending away an aide who handed the President some papers to review, and brought Warren to bed.[76]

After a group of Congressman undertook an investigation of the Veteran's Bureau and Charles Forbes was shown to display criminal behavior rather than simply being a shoddy administrator, Florence was furious. She felt personally betrayed by Forbes and wanted him dismissed at once. Warren, on the other hand, refused to believe Forbes was corrupt, looking for further information. When this information turned out to incriminate him, the President refused to accept it, and sent Harry Daugherty away when he rattled off some allegations. Florence eventually persuaded her husband to fire him, after throttling Forbes by the neck. Forbes officially resigned on February 1 from the Veteran's Bureau. His treachery caused Florence to call in Madame Marcia to see whom else of her husband's associates might be treacherous. During this period, she increasingly retreated from the public eye, with her only public act being participating in a national fuel curfew in response to shortages.[77]

In early March, shortly before a planned trip to Florida, Florence was informed that Albert Fall was leaving the Interior Department as a Standard Oil agent, and she hastily organized a dinner in his honor. Before accepting the resignation, Warren urged Fall to talk to his wife, but she could not convince him to stay. By March 5, the Hardings and Evalyn took off for Florida. During a stop in Cocoa Beach, Florence met up with her brother Cliff and his family. She enjoyed her stay in Miami, with the city using the Presidential visit as a selling point for developers. Warren continued his run of poor health, especially heart issues, though Florence remained unaware of this. During an interview with a reporter, she mentioned she wished to travel to Alaska to see what could be done to bring its tremendous natural resources to the public. After ten days in Miami, they went first to St. Augustine and then Jacksonville.[78]

In interviews with reporters, Florence indicated that she wanted to get back to doing things due to her return to health. An example of this was lobbying against the purchase of a property to be used as the Vice President's official residence. By the spring of 1923, Florence had learned of Fall's seemingly legal leasing of Teapot Dome to Harry F. Sinclair, whom Florence had recently met. She also became aware of Harding associate Jess Smith's illegal efforts, which was only confirmed during a session with Madame Marcia. After being largely snubbed by the President and First Lady, Smith died of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound on May 30.[79]

Despite having recently turned to Harry Daugherty for advice on the management of some of her assets, Florence began to distance herself from him due to the suspicion that he played a part in Smith's death. She also distanced herself from Evalyn somewhat, not visiting her house though she did send flowers and notes. In the midst of Smith's death and its subsequent fallout, the Hardings were planning an exhausting cross-country trip. Warren was to give seventy speeches in major cities throughout the country. The trip was to include Florence's long-anticipated excursion to Alaska. A diversion from the planning was a set of speeches Florence gave to Big Brothers and Sisters and the National Conference of Social Work. During a convention of Shriners in June, Florence played a prominent role, conducting the band in a parade and selling pictures of Laddie Boy for animal rights organizations. Warren gave a speech denouncing hate groups though it was falsely reported by some outlets he had joined the Ku Klux Klan.[80]

Warren decided to draw up a new will after the festivities ended. This prompted Florence to have another reading with Madame Marcia, who predicted the President would not live to 1925. Dr. Sawyer assured her that Warren was in excellent physical condition, though an examination by a different doctor revealed heart trouble. Several Senators urged him not to go on the trip. As a precautionary measure several medical personnel were to follow his every move, per Florence's wishes. After almost a year of being out of the limelight, Florence longed for the adoring crowds she was expecting to meet. Although it was ultimately Warren's decision with regards to the Alaska trip, Florence was determined to go despite the consequences.[81]

But she also moved with the times: flying in planes, showing after-dinner movies. She was the first First Lady to vote, operate a movie camera, own a radio, or invite movie stars to the White House.[82]

Florence was a friend and confidante of Evalyn Walsh McLean, the high-profile heiress, and socialite.

Death of Warren Harding

By 1923, both Florence and her husband were suffering from dangerous illnesses, but still undertook a coast-to-coast rail tour, which they called the Voyage of Understanding. Florence proved highly popular at their many scheduled stops, but Warren was visibly ailing. After falling seriously ill while visiting British Columbia, Harding died at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco on August 2, 1923.

On this tour, Warren had been under the care of Charles Sawyer, who is believed to have misdiagnosed the President's condition, and administered stimulants that brought on his fatal heart attack. As Florence did not request an autopsy, and also destroyed many of his papers, a conspiracy theory was put forward in a semi-fictional book The Strange Death of President Harding, sensationally claiming that Florence had poisoned her husband, a suggestion that has been entirely discredited, along with the book in which it was published.

Widowhood

Florence had intended to make a new life in Washington and was planning a tour of Europe. But when her kidney ailment returned, she followed Sawyer's advice, and took a cottage in the grounds of his sanitarium in Marion. Her last public appearance was at the local Remembrance Day parade where she stood to salute the veterans. On November 21, 1924, she died of renal failure.

Her grandchildren, George Warren and Eugenia DeWolfe, were the principal heirs to her estate.

Until the completion of the Harding Tomb, her body lay with that of her husband in the common receiving vault at Marion's city cemetery.[83]

References

- "First Lady Biography: Florence Harding". Canton, Ohio: National First Ladies' Library. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- Anthony, Carl Sferranza (1998). Florence Harding: The First Lady, The Jazz Age, and the Death of America's Most Scandalous President. W. Morrow & Company. pp. 1-12. ISBN 0688077943.

- Anthony 1998, pp. 14-15

- Anthony 1998, pp. 18-21

- The Marion Star, Tuesday, January 27, 1880, page 4

- The Marion Star, Saturday, January 31, 1880, page 4

- , Anthony 1998, pp. 25-27

- Anthony 1998, p. 33

- Dean, John (2004). Warren G. Harding. Henry Holt and Co. pp. 18-19. ISBN 0-8050-6956-9.

- Gutin, Myra G. "Harding, Florence Kling deWolfe". American National Biography Online.(subscription required)

- Anthony 1998, pp. 38-43

- Anthony 1998, p. 44

- Dean 2004, p. 21.

- Anthony 1998, p. 66

- Dean 2004, p. 22.

- Anthony 1998, pp. 49-51

- Anthony 1998, pp. 52-54

- Sibley, Katherine A. S. (2009). First Lady Florence Harding: Behind the Tragedy and Controversy. University Press of Kansas. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7006-1649-7.

- Anthony 1998, pp. 72-73

- Anthony 1998, pp. 75-77

- Anthony 1998, pp. 79-80

- Anthony 1998, p. 81

- Watson, Robert P. (2004). Life in the White House: A Social History of the First Family and the President's House. SUNY Press. p. 214. ISBN 0791460983.

- Anthony 1998, p. 99

- Anthony 1998, pp. 100-101

- Anthony 1998, pp. 103-105

- Anthony 1998, pp. 107-109

- Anthony 1998, pp. 110-111

- Anthony 1998, pp. 112-115

- Anthony 1998, pp. 119-121

- Anthony 1998, pp. 123-125

- Anthony 1998, pp. 130-131

- Anthony 1998, pp. 139-140

- Anthony 1998, pp. 145-146

- Anthony 1998, pp. 151-153

- Anthony 1998, p. 154

- Anthony 1998, p. 157

- Anthony 1998, pp. 159-160

- Florence Harding Biography National First Ladies Library

- Anthony 1998, pp. 187-188

- Anthony 1998, p. 190

- Anthony 1998, pp. 205-207

- Anthony 1998, p. 215

- Anthony 1998, p. 175

- Anthony 1998, p. 236

- Anthony 1998, pp. 240-241

- Anthony 1998, p. 259

- Anthony 1998, p. 245

- Anthony 1998, p. 260

- Anthony 1998, p. 248

- Anthony 1998, p. 261

- Anthony 1998, pp. 263-267

- Anthony 1998, pp. 270-271

- Anthony 1998, pp. 272-273

- Anthony 1998, pp. 274-276

- Anthony 1998, pp. 278-280

- Anthony 1998, pp. 281-282

- Anthony 1998, pp. 285-288

- Anthony 1998, pp. 299-300

- Anthony 1998, p. 207-308

- Anthony 1998, pp. 309-311

- Anthony 1998, p. 244

- Anthony 1998, pp. 326-327

- Anthony 1998, pp. 313-314

- Anthony 1998, pp. 315-316

- Anthony 1998, pp. 323-325

- Anthony 1998, pp. 338-339

- Anthony 1998, p.. 341-342

- Anthony 1998, pp. 343-344

- Anthony 1998, pp. 347-349

- Anthony 1998, pp. 351-353

- Anthony 1998, pp. 357-364

- Anthony 1998, pp. 371-377

- Anthony 1998, pp. 378-381

- Anthony 1998, pp. 382-385

- Anthony 1998, pp. 386-388

- Anthony 1998, pp. 389-391

- Anthony 1998, pp. 395-398

- Anthony 1998, pp. 400-406

- Anthony 1998, pp. 410-412

- Anthony 1998, pp. 415-420

- "Little-known facts about our First Ladies". Firstladies.org. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- The Harding Memorial, Harding Home, 2010. Accessed 2013-09-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Florence Harding. |

- Works by or about Florence Harding at Internet Archive

- Florence Harding - National First Ladies' Library

- Florence Harding at C-SPAN's First Ladies: Influence & Image

- Presentation by Carl Sferrazza Anthony on Florence Harding: The First Lady, the Jazz Age, and the Death of America's Most Scandalous President, June 23, 1998

| Honorary titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Esther Gordon |

Second Lady of Ohio 1904–1906 |

Succeeded by Caroline Harris |

| Preceded by Edith Wilson |

First Lady of the United States 1921–1923 |

Succeeded by Grace Coolidge |