Carrie Fulton Phillips

Caroline "Carrie" Phillips (née Fulton; September 22, 1873 – February 3, 1960) was a mistress of Warren G. Harding,[1][2] 29th President of the United States. The young Carrie Fulton was known by admirers to have epitomized the Gibson Girl portrait of beauty, a look popular at the turn of the 20th century. Her relationship with Senator Warren G. Harding was kept secret from the public during its time and for decades thereafter. The affair ended when Phillips blackmailed Harding during the Senator's run for office for President of the United States.[3]

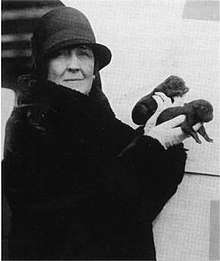

Carrie Fulton Phillips | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Caroline Fulton September 23, 1873 near Bucyrus, Ohio |

| Died | February 3, 1960 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | USA |

| Known for | The mistress of Warren G. Harding from 1905 until 1920 |

Phillips is the only woman known to have successfully blackmailed a major United States political party.[4]

Early life

Born September 22, 1873, in Dayton, Ohio, Phillips was the only daughter of Matthew Henry Fulton (1840–1906) and his wife Kate M. Swingly (1851 – after 1873).[5] She had five younger brothers: George Fred, Percy Matthew, James Edward, Thomas Durman, and Chester Courtney Fulton.[6] She was raised by her parents in Bucyrus, Ohio, where her father was a telegraph operator.

Her paternal grandfather, George Washington Fulton (1802–1864), was a successful businessman and engineer[7] active in developing the town of New Brighton, Pennsylvania. George married Mary Ann Kennedy (1812–1887), a sister of Matthew T. Kennedy (1804–1884) and Samuel Kennedy (1810–1886), brothers who established the Kennedy Keg Works first at Fallston, Pennsylvania (1836), and later opened a second operation in New Brighton (1876). George was successful in various ventures, from lumber to real estate, some in connection with his brothers-in-law, with his family reaping the advantages of his success in wealth, comfort, and education.

Carrie married James Phillips in 1896,[8] and the couple moved to Marion where Phillips was co-proprietor of the Uhler-Phillips Company, one of Marion's leading dry goods establishments. The couple quickly established themselves as active members of the local society, in large part due to Phillips’ charm and beauty. Among Phillips's friends and confidants was Florence Harding, wife of the owner and publisher of the city's leading newspaper, The Marion Star.

Affair with Warren Harding

James and Carrie had two children, daughter Isabelle (1897–1968) and son James, Jr. (1899–1901). The boy died as a toddler, and, during this time of grief Mrs. Phillips and Warren Harding grew close, despite their respective marriages and friendships. The Phillipses and the Hardings undertook tours of Europe together, all while Phillips and Harding carried on their intimate relationship.

After the affair came to light, Florence Harding, Warren's wife, was furious and reportedly felt betrayed. She claimed that this was not the first time that her husband had entered into an affair with a woman whom she considered a friend. To separate the two lovers and allow time for the respective marriages to be reconciled, the Phillips family returned to Europe, leaving the Hardings in Marion. While in Germany, Mrs. Phillips became immersed in German culture. She chose to stay in Germany and enrolled their daughter in school there. James Phillips returned to the United States alone.

While Mrs. Phillips was in Europe, Harding ran for the United States Senate. As Europe moved closer to the brink of war, Phillips returned to the United States. Her passion for Germany was very well known. Upon returning to Marion, Phillips' affair with Harding reignited. Phillips reportedly threatened to expose the affair if Harding voted in favor of war with Germany.[9]

In the summer of 1920 immediately following his acceptance of the Republican Party nomination, Harding disclosed his affair with Mrs. Phillips to Republican Party officials, also disclosing that Phillips was in the possession of hundreds of love letters he had written to her, many on Senate stationery. Reportedly wary of a scandal involving an affair as well as Phillips' support of the German government, the Republican Party urged Mr. and Mrs. Phillips to keep their travels abroad a private matter. Mrs. Phillips responded by dictating terms under which she would consider the party's wishes. In return for Phillips' silence on the matter, the Republican Party offered to pay the way for an extended tour of Asia and the Pacific Islands, as well as an annual stipend to Phillips for the remainder of her life.[10]

In June 1923, Warren Harding embarked on a western tour of the United States despite a recent decline in health. Harding died in San Francisco, California, on August 2.[11] The cause of death has been a matter of speculation. Rumors hold that he: succumbed to poison by his wife, Florence; was accidentally prescribed stimulating medicines resulting in death; was a victim of food poisoning resulting in death; or died as a result of a heart attack.[12] Mrs. Harding died 15 months later on November 22, 1924 in Marion, Ohio.[13]

After the affair

After Mrs. Harding's death, Mrs. Phillips relocated to Germany. Mr. Phillips died on July 3, 1939 at the age of 73, from heart disease.[14]

Carrie Fulton Phillips died on February 3, 1960 at the age of 86.[15] She was buried in Marion Cemetery, next to her husband and infant son. Their daughter Isabelle and her husband William Helmuth Mathee are also buried in the family plot. Isabelle and Mathee had a son, also named William Helmuth Mathee (1920–1988).

Following Phillips' death, the love letters to Warren Harding became the centerpiece of a court battle that pitted Phillips’ daughter, Isabelle Phillips Mathee, against nephews of Warren G. Harding. The Library of Congress publicly opened letters between Phillips and Harding on July 29, 2014.[16]

In a subsequent legal action, Isabelle Mathee joined the Hardings and received a temporary injunction that prevented historian Francis Russell's inclusion of the material in his book, The Shadow of Blooming Grove. Ultimately, the court ruled the letters would be sealed until July 2014, at which time their contents would be made public. The material is now in the possession of the Library of Congress, with copies held at Ohio Historical Society.[9]

Love letters

In 1964, about 1,000 pages of love letters written by Harding to Phillips between 1910 and 1920 were discovered. The letters were written while Harding was Lieutenant Governor of Ohio and subsequently as a sitting US senator. Upon discovery, the letters were sealed and handed over to the Library of Congress on condition that they not be released to the general public for 50 years.[17] On July 29, 2014, 1000 pages of the Harding-Phillips love letters became public. In 2009, the historian and lawyer James Robenalt published a smaller collection of letters, based on microfilm copies located in Cleveland’s Western Reserve Historical Society. This collection has been reproduced in Robenalt’s book, The Harding Affair: Love and Espionage During the Great War.[18][19]

References

- Ohio, Deaths, 1908–1932, 1938–2007; Detail: Certificate: 14694; Volume: 16068

- Robenalt, James David, The Harding Affair: Love and Espionage during the Great War, Palgrave Macmillan: 2009.

- Weiland, Noah (July 23, 2014). "Harding's Love Letters to Mistress May Actually Help His Image, Historians Say". ABC News. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

The affair ended when Phillips blackmailed Harding after entering the White House in 1921.

- The Washington Post Company | June 7, 1998 | Carl Sferrazza Anthony, "A President Of the Peephole", accessed April 9, 2014

- 1880 United States Federal Census; Detail: Year: 1880; Census Place: Bucyrus, Crawford, Ohio; Roll: 1003; Family History Film: 1255003; Page: 346A; Enumeration District: 097; Image: 0707

- 1900 United States Federal Census; Detail: Year: 1900; Census Place: Marion Ward 3, Marion, Ohio; Roll: 1302; Page: 19A; Enumeration District: 0060; FHL microfilm: 1241302

- 1860; Census Place: New Brighton, Beaver, Pennsylvania; Roll: M653_1071; Page: 495; Image: 501; Family History Library Film: 805071

- 1900 United States Federal Census; Detail: Year: 1900; Census Place: Marion Ward 3, Marion, Ohio; Roll: 1302; Page: 19A; Enumeration District: 0060; FHL microfilm: 1241302

- Smith, Jordan Michael (July 7, 2014). "The Letters That Warren G. Harding's Family Didn't Want You to See". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Smith, Jordan Michael. "America's Horniest President". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Ancestry.com. California, Death Index, 1905-1939 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

- The National First Ladies' Library | "First Lady Biography: Florence Harding", accessed April 9, 2014

- Ancestry.com. Ohio Obituary Index, 1830s-2011, Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

- State of Ohio, Division of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Death no. 44246

- Ohio. Division of Vital Statistics. Death Certificates and Index, December 20, 1908 – December 31, 1953. State Archives Series 3094. Ohio Historical Society, Ohio.

- Politico | "Warren Harding affair letters going public", accessed July 6, 2014

- Weiland, Noah (July 23, 2014). "Harding's Love Letters to Mistress May Actually Help His Image, Historians Say". ABC News. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- "Warren Harding letters reveal steamy side of 29th president". New York Post. July 23, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- Ruane, Michael E. (July 5, 2014). "President Harding's steamy love letters to go on display". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Robenalt, James D. The Harding Affair, Love and Espionage During the Great War Palgrave Macmillan (2009), ISBN 978-0-230-60964-8.