Ibn al-Nadim

Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Nadīm (Arabic: ابو الفرج محمد بن إسحاق النديم), also ibn Abī Ya'qūb Isḥāq ibn Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Warrāq, and commonly known by the nasab (patronymic) Ibn al-Nadīm (Arabic: ابن النديم; died 17 September 995 or 998) was a 10th-century Arab[1][2] Muslim bibliographer and biographer[3] of Baghdad who compiled the bibliographic-biographic encyclopedia Kitāb al-Fihrist (The Book Catalogue).

Biography

Much known of al-Nadim is deduced from his epithets. 'Al-Nadim' (النَّدِيم), 'the Court Companion' and 'al-Warrāq (الْوَرَّاق) 'the copyist of manuscripts'. Probably born in Baghdad ca. 320/932 he died there on Wednesday, 20th of Shaʿban A.H. 380. He was Arab perhaps of Persian origin.[1][2] From age six he would have attended a madrasa and received a quality comprehensive education in Islamic studies, history, geography, comparative religion, the sciences, grammar, rhetoric and Qurʾanic commentary. Ibrahim al-Abyari, author of Turāth al-Insaniyah says al-Nadim studied with al-Hasan ibn Sawwar, a logician and translator of science books; Yunus al-Qass, translator of classical mathematical texts; and Abu al-Hasan Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Naqit, scholar in Greek science.[4] An inscription, in an early copy of al-Fihrist, probably by the historian al-Maqrizi, relates that al-Nadim was a pupil of the jurist Abu Sa'id al-Sirafi (d.978/9), the poet Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, and the historian Abu Abdullah al-Marzubani and others. Al-Maqrizi's phrase 'but no one quoted him', would imply al-Nadim himself did not teach.[5] While attending lectures of some of the leading scholars of the tenth century, he served an apprenticeship in his father's profession, the book trade. His father, a bookdealer and owner of a prosperous bookstore, commissioned al-Nadim to buy manuscripts from dealers. Al-Nadim, with the other calligrapher scribes employed, would then copy these for the customers. The bookshop, customarily on an upper floor, would have been a popular hangout for intellectuals.[6]

He probably visited the intellectual centers at Basra and Kufa in search of scholarly material. He may have visited Aleppo, a center of literature and culture under the rule of Sayf al-Dawla. In a library in Mosul he found a fragment of a book by Euclid and works of poetry. Al-Nadim may have served as 'Court Companion' to Nasir al-Dawla, a Hamdanid ruler of Mosul who promoted learning.[7] His family were highly educated and he, or his ancestor, may have been a 'member of the Round Table of the prince'. The Buyid caliph 'Adud al-Dawla (r. 356–367 H), was the great friend of arts and sciences, loved poets and scholars, gave them salaries, and founded a significant library.[8] More probably service at the court of Mu'izz al-Dawla, and later his son Izz al-Dawlah's, in Baghdad, earned him the title. He mentions meeting someone in Dar al-Rum in 988, about the period of the book's compilation.[9] However, it is probable that, here, 'Dar al-Rum' refers to the Greek Orthodox sector of Baghdad rather than Constantinople.[10]

Others among his wide circle of elites were Ali ibn Harun ibn al-Munajjim (d. 963), of the Banu Munajjim and the Christian philosopher Ibn al-Khammar. He admired Abu Sulayman Sijistani, son of Ali bin Isa the "Good Vizier" of the Banu al-Jarrah, for his knowledge of philosophy, logic and the Greek, Persian and Indian sciences, especially Aristotle. The physician Ibn Abi Usaibia (d. 1273), mentions al-Nadim thirteen times and calls him a writer, or perhaps a government secretary.[11] Al-Nadim's kunya 'Abu al-Faraj' indicates he was married with at least one son.

In 987, Ibn al-Nadim began compiling al-Fihrist (The Catalogue), as a useful reference index for customers and traders of books. Over a long period he noted thousands of authors, their biographical data, and works, gathered from his regular visits to private book collectors and libraries across the region - including Mosul and Damascus - and through active participation in the lively literary scene of Baghdad in the period.

Religion

Ishaq al-Nadim's broad discussions of religions and religious sects in his writings and the subtleties of his descriptions and terminologies raised questions as to his own religious beliefs and affiliations. It seems Ibn Hajar's claim that al-Nadim was Shiʿah,[12] was based on his use of the term specific people (الخاصة) for the Shiʿah, general people (العامة) for non-Shiʿahs, and of the pejorative term Ḥashawīyya (الحشوية),[n 1] for Sunnis. Reinforcing this suspicion are references to the Hanbali school as Ahl al-Hadith ("People of the Hadith"), and not Ahl al-Sunna ("People of the Tradition"), use of the supplication of peace be upon him (عليه السلام) after the names of the Ahl al-Bayt (Descendants of Muhammad) and reference to the Shia imam Ali ar-Rida as mawlana (master). He alleges that al-Waqidi concealed being a Shiʿah by taqiyya (dissimulation) and that most of the traditionalists were Zaydis. Ibn Hajar also claimed al-Nadim was a Muʿtazila. The sect is discussed in chapter five of Al-Fihrist where they are called the People of Justice (أهل العدل). Al-Nadim calls the Ash'arites al-Mujbira, and harshly criticises the Sab'iyya doctrine and history. An allusion to a certain Shafi'i scholar as a 'secret Twelver', is said to indicate his possible Twelver affiliation. Within his circle were the theologian Al-Mufid, the da'i Ibn Hamdan, the author Khushkunanadh, and the Jacobite philosopher Yahya ibn 'Adi (d. 363/973) preceptor to Isa bin Ali and a fellow copyist and bookseller (p. t64, 8). Another unsubstantiated claim that al-Nadim was Isma'ili, rests on his meeting with an Isma'ili leader.[6]

Al-Fihrist

The Kitāb al-Fihrist (Arabic: كتاب الفهرست) is a compendium of the knowledge and literature of tenth-century Islam referencing approx. 10,000 books and 2,000 authors.[13] This crucial source of medieval Arabic-Islamic literature, informed by various ancient Hellenic and Roman civilizations, preserves from his own hand the names of authors, books and accounts otherwise entirely lost. Al-Fihrist is evidence of Al-Nadim's thirst for knowledge among the exciting sophisticated milieu of Baghdad's intellectual elite. As a record of civilisation transmitted through Muslim culture to the West world, it provides unique classical material and links to other civilisations.[14]

The Fihrist indexes authors, together with biographical details and literary criticism. Al-Nadim's interest ranges from religions, customs, sciences, with obscure facets of medieval Islamic history, works on superstition, magic, drama, poetry, satire and music from Persia, Babylonia, and Byzantium. The mundane, the bizarre, the prosaic and the profane. Al-Nadim freely selected and catalogued the rich culture of his time from various collections and libraries.[15] The order is primarily chronological and works are listed according to four internal orders: genre; orfann (chapter); maqala (discourse); the Fihrist (the book as a whole). These four chronological principles of its underlying system help researchers to interpret the work, retrieve elusive information and understand Ibn al-Nadim's method of composition, ideology, and historical analyses.[16]

The Fihrist shows the wealth, range and breadth of historical and geographical knowledge disseminated in the literature of the Islamic Golden Age, from the modern to the ancient civilisations of Syria, Greece, India, Rome and Persia. Little survives of the Persian books listed by Ibn al-Nadim.

The author's aim, set out in his preface, is to index all books in Arabic, written by Arabs and others, as well as their scripts, dealing with various sciences, with accounts of those who composed them and the categories of their authors, together with their relationships, their times of birth, length of life, and times of death, the localities of their cities, their virtues and faults, from the beginning of the formation of science to this our own time (377 /987).[17][1] An index as a literary form had existed as tabaqat – biographies. Contemporaneously in the western part of the empire in the Umayyad seat of Córdoba, the Andalusian scholar Abū Bakr al-Zubaydī, produced Ṭabaqāt al-Naḥwīyīn wa-al-Lughawīyīn (‘Categories of Grammarians and Linguists’) a biographic encyclopedia of early Arab philologists of the Basran, Kufan and Baghdad schools of Arabic grammar and tafsir (Quranic exegesis), which covers much of the same material covered in chapter II of Al-Fihrist.

Editions and chapters

Al-Fihrist published in 987, exists in two manuscript traditions, or "editions": the more complete edition contains ten maqalat ("discourses" - Devin J. Stewart chose to define maqalat as Book when considering the structure of al-Nadim's work).[18] The first six are detailed bibliographies of books on Islamic subjects:

- Chapter 1 Quran

- 1.1 Language and Calligraphy

- 1.2 The Torah, the Gospel

- 1.3 The Quran

- Chapter 2 Grammar

- 2.1 Grammarians of al-Baṣrah

- 2.1 Grammarians of al-Kūfah

- 2.3 Grammarians of Both Schools

- Chapter 3 Hadīth

- 3.1 Historians and Genealogists

- 3.2 Official Government Authors

- 3.3 Court Companions, Singers, and Jesters

- Chapter 4 Poetry

- Chapter 5 Theology & Dogma

- 5.1 Muslim Sects; the Mu'tazilah

- 5.2 The Shī'ah, Imāmīyah, and Zaydīyah

- 5.3 The Mujbirah (Determinists) and al-Ḥashawīyah

- 5.4 The Khawārij

- 5.5 Ascetics

- Chapter 6 Law

- 6.1 Mālik ibn Anas

- 6.2 Abū Hanīfa

- 6.3 Al-Shāfi'i

- 6.4 Dāwūd ibn 'Alī

- 6.5 Legal Authorities (Shī'a and Ismā'īlīyah)

- 6.6 Jurists of Ḥadīth

- 6.7 Al-Ṭabarī

- 6.8 Jurists of Shurāt

- Chapter 7 Philosophy and Ancient Sciences

- 7.1 Philosophy; Greek philosophers, Al-Kindī et al.

- 7.2 Mathematics and Astronomy

- 7.3 Medicine; Greek and Islāmic

- Chapter 8 Entertainment Literature

- 8.1 Storytellers and Legends,

- 8.2 Exorcists, Jugglers, Conjurers and Magicians

- 8.3 Fables and Other Topics

- Chapter 9 Religious Doctrines

- 9.1 The Ṣābians, (Manichaeans, Dayṣānīyah, Khurramīyah, Marcionites, and Other Sects)

- 9.2 Doctrines (Maqalat) of Hindus, Buddhists and the Chinese);

- Chapter 10 Alchemy.

Al-Nadim claims he has seen every work listed or relies upon creditable sources.

The shorter edition contains (besides the preface and the first section of the first discourse on the scripts and the different alphabets) only the last four discourses, in other words, the Arabic translations from Greek, Syriac and other languages, together with Arabic books composed on the model of these translations. Perhaps it was the first draft and the longer edition (which is the one that is generally printed) was an extension.

Ibn al-Nadim often mentions the size and number of pages of a book, to avoid copyists cheating buyers by passing off shorter versions. Cf. Stichometry of Nicephorus. He refers to copies by famous calligraphers, to bibliophiles and libraries, and speaks of a book auction and of the trade in books. In the opening section, he deals with the alphabets of 14 peoples and their manner of writing and also with the writing-pen, paper and its different varieties. His discourses contain sections on the origins of philosophy, on the lives of Plato and Aristotle, the origin of One Thousand and One Nights, thoughts on the pyramids, his opinions on magic, sorcery, superstition, and alchemy etc. The chapter devoted to what the author rather dismissively calls "bed-time stories" and "fables" contains a large amount of Persian material.

In the chapter on anonymous works of assorted content there is a section on "Persian, Indian, Byzantine, and Arab books on sexual intercourse in the form of titillating stories", but the Persian works are not separated from the others; the list includes a "Book of Bahrām-doḵt on intercourse." This is followed by books of Persians, Indians, etc. on fortune-telling, books of "all nations" on horsemanship and the arts of war, then on horse doctoring and on falconry, some of them specifically attributed to the Persians. Then we have books of wisdom and admonition by the Persians and others, including many examples of Persian andarz literature, e.g. various books attributed to Persian emperors Khosrau I, Ardashir I, etc.

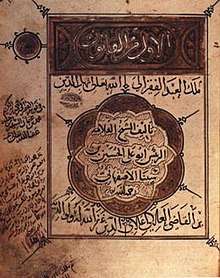

Manuscripts

- Old Paris MS - four chapters

- MS Istanbul, copy transcribed by Aḥmad al-Miṣrī for de Slane’s use in Paris

- Vienna MS - two copies

- Leiden MS - several fragments

- Beatty MS - MS no. 3315, Chester Beatty Library in Dublin; up to Chap. V, §.I, (account of al-Nashi al-Kabir). 119 f.f., handwriting in an old naskh script; belonged to historian Aḥmad ibn ‘Ali al-Maqrīzī.[n 4] The Beatty MS, a copy of the original, probably escaped destruction at Baghdad in 1258, having been taken to Damascus where in 1423 the historian Aḥmad ibn ‘Alī al-Maqrīzī acquired it. At the fall of Aḥmad Pāshā al-Jazzār (d.1804) it was in the library of the great mosque at ‘Akkā and the manuscript was probably divided when stolen from there, and later the first half was sold by the dealer Yahudah to the collector Chester Beatty for his library at Dublin.

- MS 1934 - library adjacent to Süleymaniye Mosque Istanbul; “Suleymaniye G. Kütüphanesi kismi Shetit Ali Pasha 1934”; from Chap. V, §.2., an account of al-Wāsiṭī.

- MS 1134 (no. 1134) & MS 1135 (no. 1135) - Koprülü Library, Istanbul.

- Tonk MS - Sa‘īdīyah Library at Tonk, Rajasthan it originally belonged to the Nabob.[n 5][23]

- MS 4457 - Bibliothéque nationale Paris; Fonds Arabe, 1953; cat., p.342 (cf. 5889, fol. 128, vol. 130), No. 4457; first part; (AH 627/1229-30 CE); 237 folios.

- MS 4458 -BNP; Fonds Arabe, 1953; cat., p.342 (cf. 5889, fol. 128, vol. 130), No. 4458.

- Vienna MSS - Nos. 33 & 34.

- Leiden MS (No. 20 in Flügel)

- Ṭanjah MS -(Majallat Ma‘had al-Khuṭūṭ al-‘Arabīyah, published by the League of Arab States, Cairo, vo. I, pt 2, p. 179.)

- Aḥmad Taymūr Pasha Appendix - Al-Fihrist, Egyptian edition, Cairo, Raḥmānīyah Press, 1929.

See also

Notes

- Ḥashawīyya means those who believe Allah can be confined to physical dimensions.

- lack part of Chap V, §.I, material on Muʿtazila sects

- additional to Flügel’s MSS

- Aḥmad ibn ‘Ali al-Maqrīzī, historian Abū al-‘Abbās Aḥmad ibn ‘Alī ibn ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Maqrīzī (1365-1441), native of Ba‘albek, became an official at Damascus but later lived in Egypt, where he died; one of the greatest medieval Egyptian historians. [21][22]

- Johann Fück, ZDMG, New Ser. XV, No. 2 (1936), 298—321

References

- Nicholson, p. 362.

- Gray, p. 24.

- iranicaonline.

- Dodge, p. xvii.

- Dodge, p. xxvi.

- Dodge, p. xviii.

- Dodge, p. xx.

- Fück, p. 117.

- Dodge, p. xxi.

- Nallino.

- Usaybi'ah, Part I, p. 57

- Hajar, Lisān al-Mīzān, pt.5, p. 72

- The Biographical Dictionary of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Volume 2, Numero 2, p. 782

- Dodge, p. i.

- LLC, pp. 16-17.

- Stewart, pp. 369–387.

- Dodge, pp. 1-2.

- Devin J. Stewart: The structure of the Fihrist

- Dodge, p. xxiv, I.

- Dodge, pp. xxiv-xxxiv, I.

- Ziriklī, p. 172, I.

- Enc. Islam, p. 175, IV.

- Ṭūsī, p. 315, Fihrist al- Ṭūsī.

Sources

- Dodge, Bayard, ed. (1970), The Fihrist of al-Nadīm: A Tenth-Century Survey of Islamic Culture, 2, translated by Dodge, New York: Columbia University Press[complete English translation].

- Fück, Johann Wilhelm. Eine arabische Literaturgeschichte aus dem 10. Jahrhundert n. Chr.

- ibid., Die arabischen Studien in Europa bis in den Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts., viii, Leipzig, p. 335

- Goldziher, Ignác, Beiträge zur Erklärung des Kitâb al-Fihrist

- Gray, Louis Herbert (1915), Iranian material on the Fihrist (3/1 ed.), Le Muséon, p. 24–39

- The Card Catalog Books, Cards, and Literary Treasures, California: The Library of Congress, Chronicle Books LLC, 2017, ISBN 9781452145402

- Nadīm (al-), Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq Abū Ya‘qūb al-Warrāq (1871), Flügel, Gustav (ed.), Kitab al-Fihrist, Leipzig: Vogel

- Nallino, Carlo Alfonso. Ilm al-falak: Tarikhuhu ind al-Arab fi al-qurun al-wusta (Astronomy: the history of Arabic Writers of the Middle Ages).

- Nicholson, Reynold A (1907), A Literary History of the Arabs, Cambridge: T.F. Unwin, ISBN 9781465510228

- Ritter, Hellmut (1928), "Zur Überlieferung des Fihrist", Philologika I (Der Islam 17 ed.): 15–23

- Stewart, Devin (August 2007). "The Structure of the Fihrist: Ibn al-Nadim as Historian of Islamic and Theological Schools". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 39 (3): 369–387. doi:10.1017/S0020743807070511. JSTOR 30069526.

- Ṭūsī (al-), Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan (1855). Sprenger, Aloys (ed.). "Fihrist'al-Ṭūsī (Tusy's List of Shy'ah Books and 'Alam al-Hoda's Notes on Shy ah Biography)". Bibliotheca Indica. Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, Baptist Mission Press (71, 91, 107).

External links

- Encyclopaedia Iranica

- Arabic text of the Fihrist. with notes and an introduction in German. Leipzig, 1872. PDF format.

- Chapter 7 the Fihrist in English. English translation by Bayard Dodge. PDF format.