Syriac literature

Syriac literature is the literature written in Classical Syriac, the literary and liturgical language in Syriac Christianity.

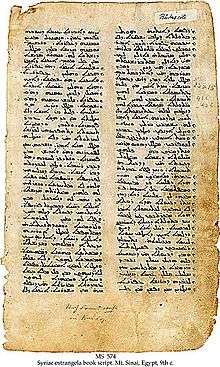

Early Syriac texts still date to the 2nd century, notably the Syriac Bible and the Diatesseron Gospel harmony. The bulk of Syriac literary production dates to between the 4th and 8th centuries. Syriac literacy survives into the 9th century, but Syriac Christian authors in this period increasingly write in Arabic. The emergence of spoken Neo-Aramaic is conventionally dated to the 13th century, but there are a number of authors that continue to produce literary works in Syriac in the later medieval period, and literary Syriac (ܟܬܒܢܝܐ Kṯāḇānāyā) continues to be in use among members of the Syriac Orthodox Church.

History

"Classical Syriac" is the term for the literary language as it developed by the 3rd century. The language of the first three centuries of the Christian era is also known as "Old Syriac" (but sometimes subsumed under "Classical Syriac").

The earliest Christian literature in Syriac was biblical translation, the Peshitta and the Diatessaron. Bardaisan was an important non-Christian (Gnostic) author of the 2nd century, but most of his works are lost and only known from later references. An important testimony of early Syriac is the letter of Mara bar Serapion, possibly written in the late 1st century (but extant in a 6th- or 7th-century copy).

The 4th century is considered to be the golden age of Syriac literature. The two giants of this period are Aphrahat, writing homilies for the church in the Persian Empire, and Ephrem the Syrian, writing hymns, poetry and prose for the church just within the Roman Empire. The next two centuries, which are in many ways a continuation of the golden age, sees important Syriac poets and theologians: Jacob of Serugh, Narsai, Philoxenus of Mabbog, Babai the Great, Isaac of Nineveh and Jacob of Edessa.

There were substantial efforts to translate Greek texts into Syriac. A number of works originally written in Greek survive only in Syriac translation. Among these are several works by Severus of Antioch (d. 538), translated by Paul of Edessa (fl. 624). A Life of Severus was written by Athanasius I Gammolo (d. 635). National Library of Russia, Codex Syriac 1 is a manuscript of a Syriac version of the Eusebian Ecclesiastical History dated to AD 462.

After the Islamic conquests of the mid-7th century, the process of hellenization of Syriac, which was prominent in the sixth and seventh centuries, slowed and ceased. Syriac entered a silver age from around the ninth century. The works of this period were more encyclopedic and scholastic, and include the biblical commentators Ishodad of Merv and Dionysius bar Salibi. Crowning the silver age of Syriac literature is the thirteenth-century polymath Bar-Hebraeus.

The conversion of the Mongols to Islam began a period of retreat and hardship for Syriac Christianity and its adherents. However, there has been a continuous stream of Syriac literature in Upper Mesopotamia and the Levant from the fourteenth century through to the present day. This has included the flourishing of literature from the various colloquial Eastern Aramaic Neo-Aramaic languages still spoken by Assyrian Christians. This Neo-Syriac literature bears a dual tradition: it continues the traditions of the Syriac literature of the past, and it incorporates a converging stream of the less homogeneous spoken language. The first such flourishing of Neo-Syriac was the seventeenth century literature of the School of Alqosh, in northern Iraq. This literature led to the establishment of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic and so called Chaldean Neo-Aramaic as written literary languages. In the nineteenth century, printing presses were established in Urmia, in northern Iran. This led to the establishment of the 'General Urmian' dialect of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic as the standard in much Neo-Syriac Assyrian literature. The comparative ease of modern publishing methods has encouraged other colloquial Neo-Aramaic languages, like Turoyo and Senaya, to begin to produce literature.

List of Syriac writers

- Mara bar Serapion (author of an early (1st century?) Syriac letter preserved in a 6th or 7th-century ms.)

- Bardaisan (2nd century)

- Aphrahat 270-345

- Ephrem the Syrian (d. 373).

- Isaac of Antioch (5th century)

- Narsai (5th century)

- Stephen Bar Sudhaile (late 5th c.)

- Jacob of Serugh (d. 521)

- Philoxenus of Mabbug (d. 523)

- Paul of Edessa (fl. 624), translator of the (Greek) works of Severus of Antioch (d. 538)

- Sergius of Reshaina (d. 536)

- John of Ephesus (d. 588)

- Peter III of Raqqa (d. 591)

- Babai the Great (d. 628)

- Athanasius I Gammolo (d. 635)

- Marutha of Tikrit (d. 649)

- Sahdona (d. c. 650)

- John bar Penkaye (late 7th c.)

- Isaac of Nineveh (d. 700)

- Jacob of Edessa (d. 708)

- Theodore Bar Konai (8th century)

- John of Dalyatha (d. c. 780)

- Theodore Abu Qurrah (d. 823)

- Anthony of Tagrit (9th century)

- Theodosius Romanus (9th century)

- Thomas of Marga (9th century)

- Jacob Bar-Salibi (12th century)

- Bar Hebraeus (13th century)

- Giwargis Warda (13th century)

- Abdiso Brika bar (d. 1318)

See also

- Patrologia Orientalis

- Alphonse Mingana (manuscript collector)

- Addai Scher (editor)

- Kitab al-Huda

References

- This manuscript was previously misidentified as a translation of John Chrysostom's Homilies on the Gospel of John. It has subsequently been identified as missing pages from a Syriac witness to the Asceticon. See J. Edward Walters, "Schøyen MS 574: Missing Pages From a Syriac Witness of the Asceticon of Abba Isaiah of Scete," Le Muséon 124 (1-2), 2011: 1-10.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). Syriac Studies: A Classified Bibliography, 1960-1990. Kaslik: Parole de l'Orient.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1997). A Brief Outline of Syriac Literature. Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron Michael Butts, George Anton Kiraz & Lucas Van Rompay (eds.), Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage, Piscataway (NJ), Gorgias Press, 2011

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- William Wright: A Short History of Syriac Literature, 1894, 1974 (reprint)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Syriac Literature. |

- HUGOYE: Journal of Syriac Studies

- Syriac Literature

- Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Computing Institute

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Anton Baumstark's Geschichte der syrischen Literatur, (1922)